How long could you drive without dozing off? Maybe 8 hours? Possibly 10? How many hours do you think a long-haul trucker could drive without swerving into your lane? Would you ever want an 80,0000 pound rig coming at you with a guy behind the wheel who hadn’t slept in a day? Want to buckle yourself into your seat on a plane with a pilot cat napping on the control panel? How about a sleepy surgeon coming toward you with a scalpel? Does that seem like a good idea?

Sleep deprivation is more dangerous than working under the influence of alcohol. In fact, being awake for at least 24 hours is like having a blood alcohol content of 0.10% (higher than the legal limit in all states). Fatigue leads to car wrecks, plane crashes, and fatal medical mistakes. Thankfully, most employers have excellent safeguards so workers are well rested to prevent these catastrophes. Except for hospitals.

Today a reporter from Medical Economics interviewed me about the new debate over loosening the current work-hour restrictions for physicians-in-training. A proposal set to be finalized in the next few weeks would allow first-year residents to work shifts of up to 28 hours without sleep (as all other residents are already allowed to do) and would even allow any resident to work an unlimited number of hours without sleep without having to justify or document why they did so. I got pretty revved up so here’s a quick recap to get you up to speed.

Doctors-in-training (fresh med school grads) are called residents because they basically reside in the hospital and function as cheap labor (divide salary by hours worked and they earn less than minimum wage). Residents have traditionally worked grueling schedules with up to 72-hour shifts—or more. Though sleep deprivation is recognized as a torture technique and a violation of human rights, in medicine it’s a lifestyle, a rite of passage—even a badge of honor.

The truth is sleep-deprived residents have been running US hospitals for decades.

Until all hell broke loose in 1984 when Libby Zion (an 18-year-old college student) died in a New York hospital. Her father (a lawyer and well-connected journalist) stated, “I left her there with an earache and a fever” and “they sent her home in a box.” He soon discovered that her care was left to sleep-deprived residents without supervision. Legal battles ended with a 1989 New York Health Department requirement that doctors-in-training have adequate supervision and work no more than 24 consecutive hours with an average work week of 80 hours (rather than 100+). In 2003 the ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education) applied these work-hour limits to all US residents. In 2011 ACGME capped first-year residents’ shifts at 16 hours. Note: work-hour restrictions remain unenforced in many programs (I still hear from residents who work more than 120 hours per week).

Sleep deprivation doesn’t stop after residency. One newly graduated resident was so exhausted that he developed seizures right in front of hospital administrators. Their response? Send him right back into the ICU to care for the sickest patients. Some docs are even forced to work 168-hour shifts like this physician whistleblower:

You may be wondering why residents don’t complain when their programs fail to uphold work-hour restrictions. Simple. Those who speak out face retaliation from program directors that may destroy their careers. Even worse, an investigation could result in lost accreditation for the entire residency (adversely impacting the future of all physicians in the program). So nobody says anything. Violations continue. Patients die. Physicians suffer. Some are so fatigued they die in post-call car accidents because they’re unsafe to drive home after work.

So what’s being done to improve working conditions?

Disgruntled doctors who are not “team players” are mandated to resilience training courses where they’re taught “work-life balance.” Physician “wellness” conferences and programs are popping up in every hospital where doctors are encouraged to relax and take deep breaths. Problem is meditation is not the treatment for human rights violations.

Rather than strengthen protection and enforce current work-hour caps, ACGME is discussing a return to the pre-Libby-Zion days by placing interns back on 28-hour shifts because they now believe longer hours could make patient care safer due to improved continuity with the same doctor. Yet a public opinion poll reveals 86% of Americans oppose lifting the 16-hour cap on first-year doctors.

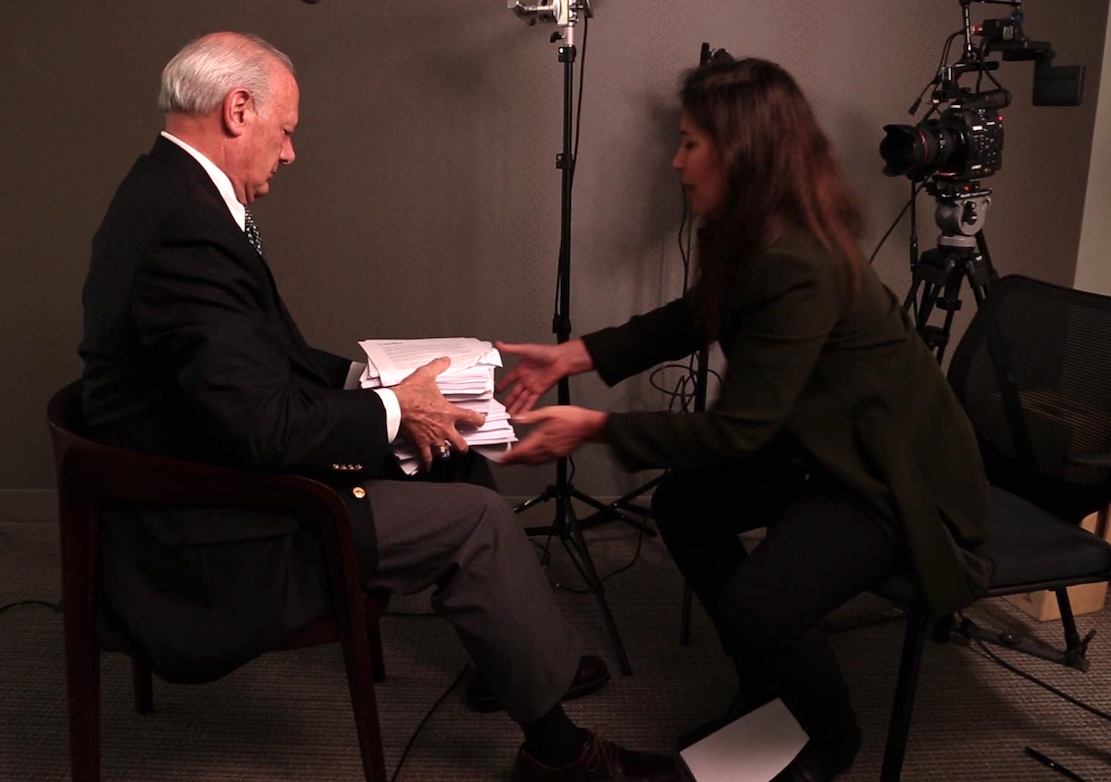

Filmmaker Robyn Symon, producer of the forthcoming physician suicide documentary Do No Harm, personally handed a petition with more than 75,000 signatures to Thomas Nasca, M.D., the CEO of ACGME, demanding the agency take action to address the rampant human rights violations in medical training that lead to high suicide among medical students and doctors.

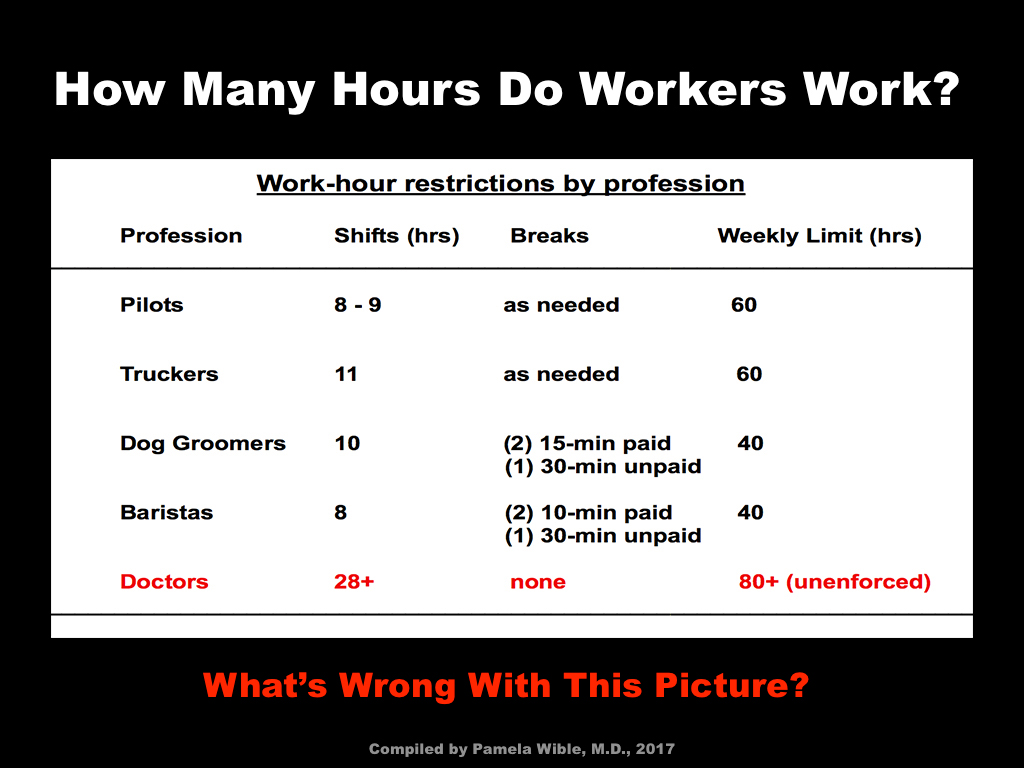

What other industry in the modern world requires employees to work 28-hour shifts? None that I’ve discovered. I wandered around town searching for anyone who works more than a day without sleep. I even interviewed PetSmart dog groomers to Starbucks baristas and spoke with pilots, truck drivers, and more. Here’s what I discovered.

Pilots fly a maximum of 9 hours during the day and 8 hours at night according to FAA regulations. Work week is 60 hours. They get bathroom breaks and can eat at their discretion and always have a co-pilot as backup. Truck drivers have strict hours-of-service limits as dictated by the Federal Motor Safety Administration. They can work 14 consecutive hours in which they can drive up to 11 hours. Maximum 60 hours work weeks. Bathroom breaks and meals are taken as needed.

My local PetSmart groomer works 8-hour shifts. During the holidays, she has witnessed a rare 10-hour shift. PetSmart groomers in Oregon must receive breaks per state labor laws and in my neighborhood they get two 15-min paid breaks and one 30-min unpaid break and generally work 40-hour work weeks which is considered full time. Similar story at my local Starbucks where baristas get two 10-min paid breaks and one 30-min unpaid break in an 8-hour shift during their 40-hour work weeks. Compare this with resident physicians who may work 28 (or more) hours per shift without breaks, meals, or sleep (with an 80-hour work week upheld by the honor system).

So what’s the worst case scenario if we don’t follow basic labor laws. At Starbucks maybe you’d get a bad cup of coffee. At PetSmart, Fluffy may be sent home with a bad haircut. No big deal. Right? Not exactly. My groomer explained that workers on long shifts are less likely to recognize animal distress resulting in dog and cat deaths during grooming.

If fatigued pilots have killed hundreds of passengers just by dozing off, if tired truckers have knocked out entire families on summer vacation, if overworked groomers could kill your dog, why are you placing your medical care in the hands of sleep-deprived doctors?

If you’re outraged, do something. Your apathy nearly guarantees that one day you and your loved ones will receive care from impaired doctors. Transform your rage into action. Libby Zion’s dad turned his fury over his daughter’s death into a teaching moment for the entire American medical education system. He’s dead now so he can’t protect us anymore. We have to save ourselves.

Please sign this petition to stop 28-hour shifts for our new doctors.

Pamela Wible, M.D., is a physician who reports on human rights violations in medicine. She is author of Physician Suicide Letters—Answered. View her TEDMED talk Why doctors kill themselves. Image credit Robyn Symon.

Great article. While I agree with you that resident’s hours should probably be limited, Libby Zion’s death was in fact not caused by sleep deprivation. Instead, it was caused by an obscure drug interaction resulting in an acute case of serotonin syndrome. It may interest you to know that during the subsequent trial, several department chairs testified that they had never heard of the drug interaction that caused her death.

I do realize that though I also think that with more supervision that her death may have been prevented. Kind of like the dog groomer paying attention to the panting pup to avert a dog’s death. I’ve read the accounts of her last few hours and she was struggling and yet the diagnosis was “viral syndrome with hysterical symptoms.”

On the hospital ward where she was sent, Libby was evaluated by two residents: Luise Weinstein, an intern eight months out of medical school, and Gregg Stone, who had one additional year of training. They, too, were not quite certain of Libby’s diagnosis. Stone termed it a “viral syndrome with hysterical symptoms,” suggesting that Libby was overreacting to a relatively mild illness. The doctors prescribed a shot of meperidine, a painkiller and sedative, to control her shaking. Sherman approved the plan by phone.

The events of the next several hours will always remain controversial. At about 3 in the morning, Weinstein went off to care for some of the 40 other patients she was covering. Stone went to sleep in an adjacent building, where he would be available, if necessary, by beeper.

After the doctors left, Libby became more agitated. The nurses contacted Weinstein at least twice. Weinstein ordered physical restraints to hold the patient down and prevent her from hurting herself. She also prescribed an injection of haloperidol, another medication aimed at calming her down. Busy with other patients, Weinstein did not reevaluate Libby.

Assembly-line medicine + sleep-deprived interns + lack of supervision = not a great scenario any way you slice it.

See public citizen comments on the ACGME’s proposal posted here (link is no longer working)

Dick writes:

Dear Pamela,

I recently returned from a visit with our daughter who is doing her residency. Your observations about some of the negatives of the indentured servant side of the first year of residency are spot on target. Excepting her one day off last week, she had perhaps three semi-functional hours daily during which we visited. In addition, as I am sure you know, the 80 hour restriction rule is regularly violated by residency programs. While residents are required to report on the hours they work each week, they know that the intern system will result in punishment if they report accurately the time they were required to work in a week (say, “85 hours”). The corporate cultural rule is ‘do not write down accurately the number of hours you have worked. Written “criticism” of the reality is more than frowned on. Medical ‘corporate culture’ is just as corrupt as say working at Walmart, or Volkswagen, etc.

My reading is that this adds to the accretion of cynicism about medical careers which builds up during training. It also adds to a sub-perception of entitlement (which maxes during the third year of medical school). And it creates an atmosphere which slowly increases critical attitudes toward patients as unappreciative people. If you know of a decent social psych study of this corrosive social atmosphere, please let me know.

Please continue your work – both noting the damaging aspects of medical training AND pointing the way forward toward more positive models of practice (post training).

What if I am on the side that believes physicians do need to learn their limits and limiting work duty hours has not improved care provided to patients when residents begin to see their job as shift work and give inadequate check out, lack commitment to their patients, and then get out in practice and don’t understand that not a single person is keeping track of their time or making sure they are doing what is right for their patient. Do you also want to hear from my side?

Absolutely Susan! This is a conversation. I am 100% open to hearing the opposing view.

I graduated 40 years ago, and took a year off to work in ER’s (before there were ER boards) between my internship and residency, in order to avoid going insane. Working insane hours may have made sense when there was no one else to do the work, and physicians were responsible for everything that happened. That social contract is now broken, physicians no longer have the control over medicine they used to, so they can’t be expected to put out like they used to. Therefore, it is society’s responsibility to patients and physicians to provide working conditions which are safe for everyone. Unfortunately it doesn’t appear that academic medicine has changed. When I was training there were very few academicians I wanted to be like. I am board certified in sleep medicine, and am still amazed at how more and more functions depend on good sleep. Real world practice is moving toward a state of allowing reasonable hours; hospitalists are one example, so there is no need for abuse during training, in fact POOR SLEEP INTERFERES WITH LEARNING. After decades and decades, it is time to treat medical trainees as the people they are, for everyone’s sake.

Funny you should mention hospitalists as a solution. The whistleblower video in the article is a hospitalist.

I spent time in the jungle getting two hours sleep a day. Doing that makes you psychotic. I went over weighing 186# and came home weighing 139#.

Then I had a job and averaged eighty-one hours a week over five years. For six weeks during that period, I didn’t work less than one hundred twenty hours a week. I went to my Grandparents for Easter and everybody said I looked like death warmed over.

That kind of working isn’t good for anyone!

Were the 120-hour weeks in a medical setting?

I do not have an issue with intern/resident hours. Post Libby Zion, I have been opposed

to some of the limitations. The problem made public by that case is more a nicety of

limited hours more rest than anything else. The issue not recognized is the hierarchy.

When the chain of command is intact and is functioning, yes we are tired and we are

hallucinating while coverage is around from the teams, med/surg/nurs etc. I have

experienced the break-down in the chain and was glad nothing untoward occurred.

Yes the every 3rd on call was rough, brutal sometimes, yet the baptism of fire, or

under fire, served the hazing delight of supervisors and gave us hard lessons, though

not really tough love lessons, and we did and we learned a lot.

But how can hallucinations ever equal great patient (or physician) care? Let me rephrase:

yes pilots are tired and they are hallucinating while coverage is around from the crew . . .

yes truck drivers are tired and they are hallucinating while coverage is around at the truck stop . . .

????

hallucinations do not equal great patient care, rather the result of 44-46 hours standing moving barely sitting down, exhaustion, the point from active movement across the clinical spectrum to the slowed down time of charting. (Great) patient is (hopefully) before the point of end-game fellow physicians at various levels and nurses and supportive adjunctive staff interdicts on behalf of patients, maybe us too. Go home, run 10 miles, burn away the 2 day day such that the next day, ending, may arrive and invite sleep. it is finite time, each year of training, practicing on poor patients to be ready for a personal patient population. it is rude crude cruel to look at patients as practice, yet that patient population helps us learn and helps some move to a lucrative practice or to a city practice, each to help people is different and same manners. I spent the majority of my time in the Hispanic community; good people.

This is inhumane. Would you endorse this in any other profession?

Dr.Pam,

I’m an advocate for interns residents and on call physicians:(having been military/medical during Vietnam) to have appropriate breaks.As a veteran; recently;I went to the chief of staff(aPsychiatrist) asking to initiate a monthly stress free “Happy Day” which would mean a day of fun activities,painting,ceramics,doodle art:basically anything to relieve stress;since art is well kmown to allieviate stress. MY REQUEST WASN’T EVEN GIVEN A BLINK,OR EVEN TRIVIAL CONSIDERATION..NO ONE;IF THEY ARE HUMAN -SHOULD EVER RISK ANOTHER’S LIFE BY SLEEP DEPRAVATION. THIS IS THE QUICKEST WAY BOTH TO KILL A PATIENT AND KILL A DOCTOR’S FUTURE.

I STAND WITH YOU,THIS IS UNCONSCIONABLE,humans are fallible;tired humans mistakes can kill.

Linda, I hear ya! I actually got in trouble and written up for being “too happy” at work. They (in essence) said I made everyone else who was miserable there feel worse.

DrPam,

I’m an advocate for interns, residents and on call physicians to have reasonable down time 2 Things: 1.our local police dept initiated a quiet room officers can use individually during lunch to chill, catch some mental, physical re-coup time. How much more shouldn’t physicians need this. Also, as former military medical personnel during wartime, I requested @ the local VETERAN’S HOSPITAL; the chief of staff (a psychiatrist herself) to initiate a stress free day once a month. As a freelance artist, I know the benefits of art as a stress reducer and just having this monthly could help greatly. I was completely ignored. Staff is apathetic,I believe- they are tired. Positive incentives. If a physician continues without rest, there is a greater chance of fatigue induced mistakes; that can cost both the pt’s life and the Dr.’s future

I’ve got a blog post and podcast on happiness coming out next week. Oh, you’ll LOVE this one. Says it all my friend.

I think the program should be public about how many hours the residents are allowed to work and then medical students have that information before they apply.

I needed unlimited hours in residency, because I wanted to take time with patients and learn more by being there. I chose a program that I knew had a somewhat more humane work load; it was a good program.

Caveat emptor is way better than trying to control everything from the top (an impossible task that always distorts the options).

Exactly. No one-size-fits-all is every going to work for everyone. Some basic guideline and labor laws (enforced) would go a long way. I am a fan of putting residents in charge of designing their own programs. See this: https://www.idealmedicalcare.org/blog/ideal-residency-therapy-dogs-scribes-time-lunch/

Per Willa Pawlikowski: “I believe the executive decisions made now are different from the past. The Residents I worked with did those hours, but we only called them if necessary. In our ICU, we made good decisions, were responsible for them and supported by our Residents, Fellows, and Attendings. I’m concerned that perhaps that culture has changed. I suggest, respectfully, that you examine the differences between those cultures and find if it’s the lack of mutual give and take. Long hours aren’t the problem if sleep is encouraged, and teams of Residents are large enough to handle all the admissions, problems, and transfers from other facilities. The magic is numbers, not hours. Billie Pawlikowski RN, BS, BSN and proudly 70 years old. We protected our Residents!”

Thank you for addressing this issue, from my perspective as a patient and advocate for better healthcare it seems insane that anyone in the health field would advocate for less than a full night’s sleep (7-8hours) for EVERY SINGLE PERSON in the whole country, including health professionals. I understand some might have to work swing shift (a whole other subject of sleep health) due to the 24hr nature of health care but that still doesn’t excuse less than 7-8hrs of sleep per 24hrs.

I often wonder if the medical profession ever reads their own studies or if they just think they don’t apply to them. Just a few days ago I read about a study from the University of Washington that shows that sleep deprivation suppresses the immune system.

How does it serve anyone if health professionals get sick and then make patients sick? Adequate sleep is a great example of how doctors should lead by example, instead they seem to prefer “do as I say, not as I do”.

Exactly. Time for health care institutions to care for their own students and employees. Criminal behavior. Frank human rights violations. No excuse.

Doctors are not robots, and medical care is not a cookie cutter factory product. It is an art as well as a science. Sleep-deprived medical professionals are not going to provide safe medical care, let alone do a nuanced, artful job of it. It makes no logical sense to overwork the people we trust with our lives.

Exactly. Dangerous for doctors & patients. Just a few examples of what can happen below:

I did my internship in internal medicine and residency in neurology before laws existed to regulate resident hours. My first 2 years were extremely brutal, working 110 – 120 hours/week, and up to 40 hours straight. I got to witness colleagues collapse unconscious in the hallway during rounds, and I recall once falling asleep in the bed of an elderly comatose woman while trying to start an IV on her in the wee hours of the morning.

I ran a red light driving home in residency after a 36 hour shift. Got pulled over. It was sobering: I was not fit to use my driver’s license, but I had just been using my MEDICAL license for over a day non-stop!

Need I share more?

Sleep deprivation is dangerous and damaging to everyone involved especially to the sleep deprived

Don’t get me started.

Absolutely not! A person under duress can only function up to 10 hours!read the research.

Yep. Common sense too. Even children know they need sleep. Or they get cranky.

I disagree as these future doctors have family and some have to travel long stretches to be aware.

Being the cynic that I am, I believe that even if the ACGME were to disallow 28-hour shifts for interns, those interns will still work shifts in excess of 28 contiguous hours but document on their time sheets in New Innovations that they only worked 16 hours or less as is the current practice.

Truth in time-keeping is something just about every GME program either actively or furtively discourages and the ACGME has absolutely no regulatory teeth to enforce its own duty-hour restrictions. I don’t ever see that changing.

You are so right. Look what happened to this doc who didn’t lie on her time sheet. She got in trouble.

During intern year at a program with a nominal 80-hour work week, I worked 100 hours per week for most of a month. I was interviewing a patient when I suddenly realized that I could not remember what I had just asked. I excused myself abruptly and rushed down the hall where I collapsed on the bathroom floor. I leaned against the wall and felt relaxed for the first time in weeks. My face was wet and I realized I was sobbing. I was so unaware of how exhausted and impaired I had become. I cried because I was tired, and also because the patient I was seeing deserved better attention and care than I was capable of providing. I couldn’t remember any details of his chest pain or risk factors for heart attack. I couldn’t even remember his name or his face. Only that he was friendly and he trusted me. I felt intensely guilty for not being able to stay awake, let alone think like a doctor. I nodded off while crying, propped up against the wall. I woke up and forgave myself. I think I was away from him for less than 10 minutes. I walked back into his exam room and said, “Where were we? Let’s start at the beginning to make sure I get this right. Because what you are saying is really important.” That month during my evaluation, my program director told me that my total number of work hours was a sign of inefficiency. I later learned that others were also working 80-100 hours per week but they falsified their hours to avoid criticism.

An email from doc:

Don’t these people read the studies??

Cognitive ability drops markedly after 6 hours. MDs are cognitive!

A dear friend from med school died during her neurosurgery residency. Drove over a median into a tractor trailer after a 30+ hour shift. She left behind her family, including a twin sister and her fiance. She was 30.

Petition the Department of Health and Human Services to limit the hours direct service providers can work consecutively. The ACGME wants to avoid this.

More on the dangers of sleep deprivation: “Just one night’s bad sleep can have fatal consequences in transportation, emergency services and war. A single night shift is enough to make even the most dedicated people sleep-deprived. Dr Steven Lockley in the Harvard Work Hours, Health and Safety Group proved that good doctors become positively dangerous during night shifts. Lockley suspected that even Harvard doctors – some of the best doctors in the world – would be deeply influenced by working night shifts. His team set up a random controlled trial to discover if this was true, and the results were truly shocking. Doctors on the 24-hour shifts (used in the US) made 36% more serious medical errors and five times as many serious misdiagnoses. Even their consultants showed an increased risk of burn-out and depression.”

I am mechanic in Michigan, I was a chief heavy truck mechanic for a fleet here in Michigan. I have worked every shift a man can work. 1st shift, 2nd and third shift, and yes all in a row as well. Although I can count on both hands in 20 years the times I worked over 24 hours. It is my opinion that after 12 hours of none stop work that their is a point that you can tell you are compromised, mentally and physically. And no I do not have a IV league education either. It is also my opinion taking that risk as a doctor, is the same as drinking a bunch of liqueur to the point of passing out, jumping in your car for a drive in rush hour traffic. You are your own boss, responsible for your actions. As a certified mechanic my boss is in control of a few things. How ever, how I repair a fleet or their customers cars is my responsibility and discretion. In other words I am as much as a boss to my boss as they are to me. And yes when employing a certified mechanic, they know it. Please tell me that doctors have the same or more control. If they do not, God help us all…..

I’m with ya Bob! And yes, God help us all! Change is coming. Check out the film trailer of forthcoming documentary that exposes all of this to the public –> http://donoharmfilm.com

I started medical school at age 19. Sometime in second year someone mentioned ‘on call’ and I said ‘What is that?’ Ha ha the joke was on me.

Let me mention another sleep deprivation factor – being a physician and young mom with a baby (and back to work at three months due to lack of maternity coverage). I used to go on call hoping that I would get a quiet night and some rest, because it certainly wasn’t going to happen at home since my baby compensated for my absence by staying up at night to breast feed!