Dr Pamela Wible has been described as medicine’s Martin Luther King. Born into a family of physicians, her parents warned her not to pursue medicine. She followed her heart only to discover that to heal her patients she had to first heal her profession. So she led a series of town hall meetings inviting citizens to design the clinic of their dreams. Celebrated since 2005, Wible’s pioneering model has sparked a populist movement that has inspired Americans to create ideal clinics and hospitals nationwide. Dr. Wible is author of Pet Goats & Pap Smears: 101 Medical Adventures to Open Your Heart & Mind and is co-author of the award-winning anthology Goddess Shift: Women Leading for a Change with Michelle Obama and Oprah Winfrey. Dr. Wible has been interviewed by CNN, ABC, CBS, and is a frequent guest on NPR.

Could you tell us about your background and what made you decide to become a doctor?

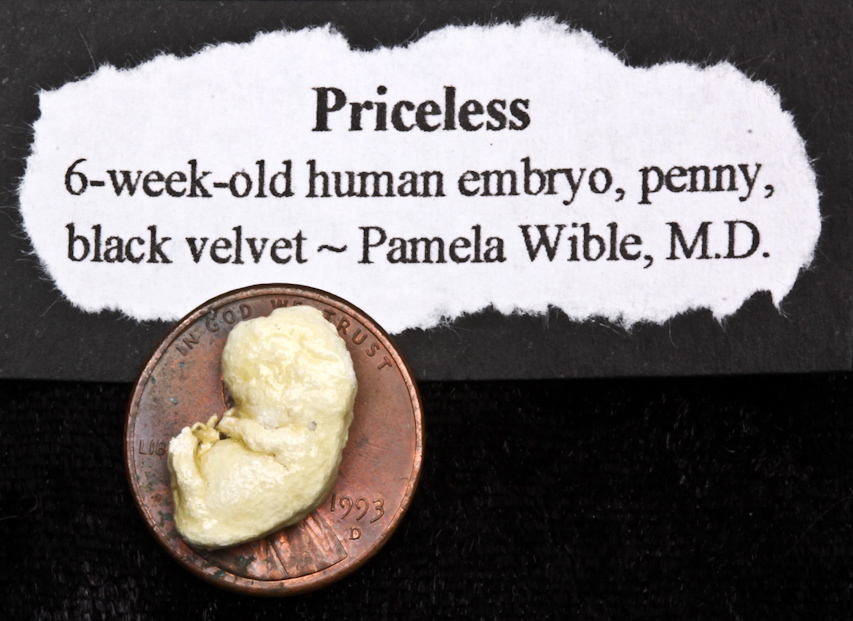

I was born to be a doctor. My parents are physicians, so it’s in my blood. In utero, I accompanied my mom, a psychiatrist, on rounds at the state hospital. Raised in a morgue, I worked alongside my dad, a pathologist. I peeked in on autopsies and examined body parts, even miscarriage specimens. Dad and I examined itty-bitty rib cages and femurs. He could age the body by the size of the bones. I thought he was amazing.

From the morgue, I followed Dad to three part-time jobs. At the Philadelphia jail during pre-breathalyzer days, on-site doctors examined drunk drivers. Bored coloring the policeman coloring book week after week, I got clearance to interview the inmates. At the methadone clinic, Dad told clients to show me their track marks. On call for the Philadelphia Fire Department, Dad would lift me from bed for late night drives to industrial warehouses engulfed in flames. I’d sip hot chocolate with Dad and the crew in the lead fire truck. Introduced as a doctor-in-training. My parents set me loose on schizophrenics, inmates, addicts, and cadavers while most girls my age were playing with Barbies. How could I not be a doctor?

You wrote the book Pet Goats & Pap Smears which has received astounding reviews. Could you tell us a bit more about the book and if you have any other books planned for the future.

This book offers what medical school doesn’t. Medical training teaches technical skills, but not the art of medicine. Doctors are taught to order blood tests and CAT scans, to diagnose and drug, to perform surgery. But we have no courses on how to serve patients with joy. We have no textbooks on love and compassion. We aren’t tested on creativity. Intuition is rarely recognized as a diagnostic tool. And all too often, we view death as our own failure. Trained to detach emotionally and spiritually from patients, medical students eventually lose connection with the meaning of life and the mystery of death.

When premedical and medical students shadow me in my office, they often tell me that I’m the first happy doctor they’ve ever met. And the only solo doctor they’ve ever known. Students tell me they have no mentors. In this book, I offer myself as a mentor to students who will never have the opportunity to hang out with me at our community clinic. Though I’ve written this book for medical students, doctors and patients love it too! This book is now taught in medical schools and undergraduate medical humanities courses. And yes! I have Pet Goats & Pap Smears sequels coming. But first I need to complete the Kindle conversion of this book . . . coming soon!

What made you decide to start a physician retreat and what did you learn from that experience?

I published Pet Goats & Pap Smears to celebrate the joy of doctoring. Two days later, a local pediatrician shot himself in the head in a public park. In just 18 months we lost three physicians in our small town to suicide. At the pediatrician’s funeral, I realized that both men I had dated in med school were dead. Brilliant physicians. Loved by their families and patients. Both died young—by suicide.Physicians have the highest suicide rate of any profession. In the United States we lose over 400 physicians per year to suicide. That’s the equivalent of an entire medical school. I was suicidal once. Assembly-line medicine was killing me. Rather than kill myself, I invited my patients to help me design an ‘ideal clinic.’ It is possible to love medicine again. I wanted to do something to help other doctors love medicine too.

I learned that doctors lack the basic skills to run a successful solo community clinic. They lack camaraderie. They lack joy. In the retreats, I teach community organizing and business strategies that doctors need to succeed. Doctors deserve to be happy, to live their dreams fearlessly.

In your opinion why have so many physicians, at one point in their life, considered suicide?

Doctors are wounded healers. Many docs tell me that they graduate medical school with PTSD. We carry the trauma from every life-and-death experience we witness in our training. We carry the pain and suffering of our patients’ lives. Yet we don’t receive mandatory mental health services to help us cope. In fact, physicians are afraid to seek mental health care due to licensing repercussions. I have compiled a list of reasons why doctors die by suicide here.

How do you personally deal with stress on a day-to-day basis?

I do not compartmentalize. I love my work. I work a humane schedule. I allow my patients to help me. I invited my patients and community to design an ‘ideal clinic.’ So many people volunteered to help open the clinic. They saved my life and my career. My patients give so much energy and love back to me. And I feel very, very supported. I have no stress.

The majority of readers of this blog are medical students. What advice would you give to any of them who may be considering suicide or who are suffering from depression?

Remember your personal statement. Honor yourself and your dreams. Ask for help. Remember that you are paying tuition to learn a skill set so that you may be the doctor you described on your personal statement. Do not settle for less. Allow classmates, patients, other doctors to help you. See a therapist or counselor. Do not isolate. Do not suffer in silence. Do not give up on your dreams. Contact me anytime. Seriously!

Are there are any clinical predictors of physician suicide? And if we are worried about a colleague, what is the best approach?

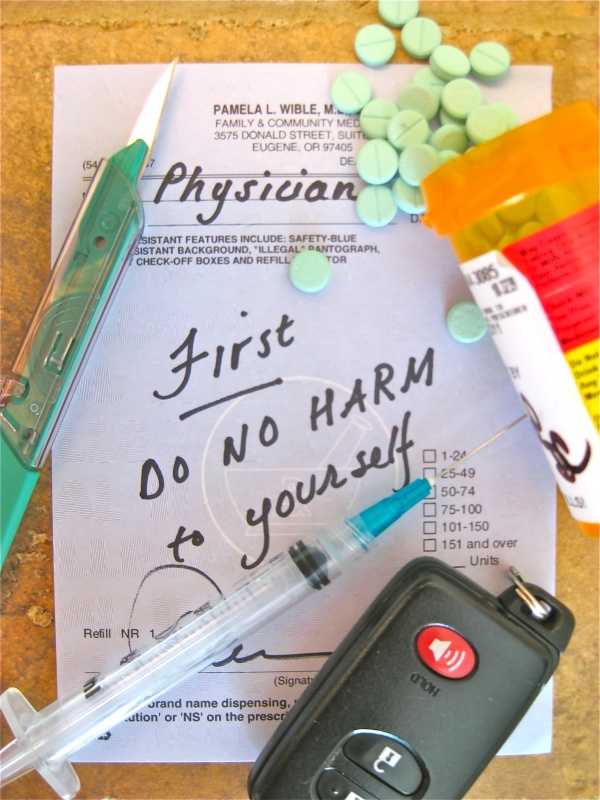

Clinical predictors are history of suicidal ideation, depression, substance abuse, isolation, pessimism, cynicism, and hopelessness. We have easy access to lethal drugs and firearms. Not a great mix. If you know a colleague who is suffering, reach out to him or her. Realize that men often have a harder time asking for help. Keep your heart open for others who may be having a hard time. Invite them to lunch. Listen to them. Sometimes just having someone to talk to is enough.

Has becoming a doctor impacted on your social life, relationships and family life?

Yes! Doctoring is my life. I love it. The key for me is working part time so I can love my personal life too.

Could you explain what an ‘ideal clinic’ is?

An ideal clinic is defined and designed by the patients and community the clinic serves. In 2005, I held town hall meetings and invited citizens to design their own ideal clinic. I collected 100 pages of written testimony, adopted 90% of feedback, and we were open just one month later. For the first time my job description had been written by patients, not administrators. My patients are my heroes. I discovered that patients and doctors want the same things. By bringing my patients’ ideal clinic to life, I was suddenly practicing medicine in the clinic of my dreams. Here’s how any community can design an ideal clinic.

If you had 1 billion dollars to improve one aspect of healthcare, what would you spend it on?

Humanizing medical education. We need happy doctors, not reductionist robots. I’d start by giving free copies of Pet Goats & Pap Smears to every premedical and medical student in the world.

Reposted from Meddebate. Interview by Jamal Ross, London, UK.

Jamal Ross, London, UK.

Pamela L. Wible, M.D. is a family physician and bestselling author of

Pamela L. Wible, M.D. is a family physician and bestselling author of