A psychiatrist in Seattle had picked out the bridge. At 3 a.m. he would swerve across his lane and plunge into the water. Everyone would assume he fell asleep.

A surgeon in Oregon was lying on the floor of her office with a scalpel. Nobody would find her until it was too late.

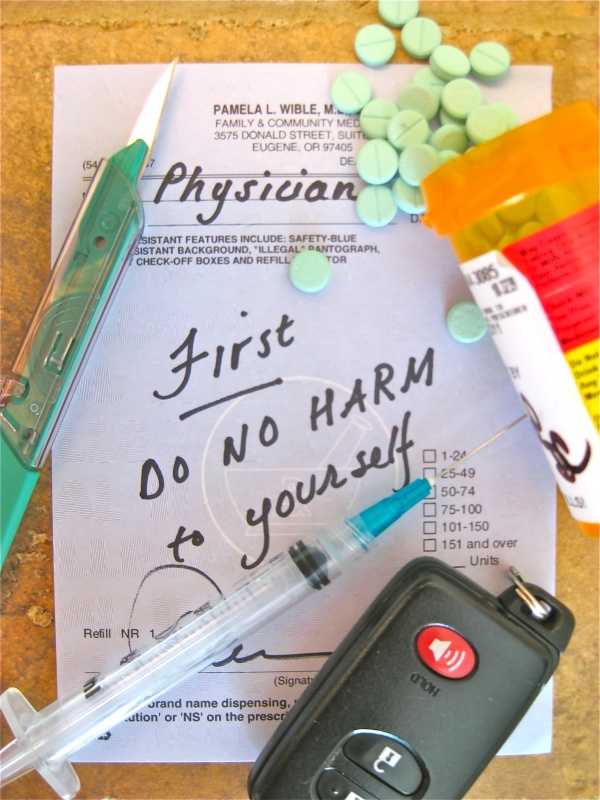

An internal medicine resident in Atlanta heard an anesthesiologist joking about the lethal dose of sodium thiopental. Alone in the call room, she would overdose that night.

Three planned suicides. All three physicians survived. Why?

While preparing to overdose, the internist was interrupted by an endocrinologist calling to check on her. Before grabbing her scalpel, the surgeon called several physicians pleading for help—I responded immediately. Two days before he was to drive off the bridge, the psychiatrist spotted my ad for a physician retreat. He called me begging to attend.

One week later, I’m hiking through the Oregon Cascades. The scent of cedar envelops me as I approach the lodge where I’m welcoming physicians who have arrived from all over the United States and Canada, all of us on a pilgrimage for answers.

Tonight we begin a retreat for doctors who yearn to love medicine again. Studies confirm most doctors are overworked, exhausted, or depressed. The tragedy: few seek help.

I ask the group, “How many physicians have lost a colleague to suicide?” All hands are raised. “How many have considered suicide?” Except for one woman, all hands remain up—including mine.

“Physicians have the highest suicide rate of any profession,” I explain. “In the United States we lose over 400 physicians per year to suicide. That’s the equivalent of an entire medical school. Even that’s an underestimate because many physician suicides are incorrectly identified as accidents.”

I tell them, “Both men I dated in med school are dead. Brilliant physicians. Loved by their families and patients. Both died young—by ‘accidental overdose.’ Really? How many physicians accidentally overdose?”

The room is quiet.

It’s easier to say accident than suicide. Doctors can say gonorrhea and carcinoma. Why not suicide? Maybe we can’t face our own wounds.

“I’m a family doc in Eugene, Oregon, where we’ve lost three physicians in eighteen months to suicide. I was suicidal once. Assembly-line medicine was killing me. Too many patients and not enough time sets us up for failure. Rather than kill myself, I invited my patients to help me design an ‘ideal clinic.’ It is possible to love medicine again.”

The Canadian doctor to my right wipes her eyes. “I’m feeling so discouraged. I want to give up and work at Starbucks. My head is exploding from banging it against the system.”

A bright-eyed, blonde woman reveals, “I just took a leave of absence from med school because it was ‘killing my soul.’ Three classmates attempted suicide.”

A newlywed couple join in. “I’m a nurse. My husband is an internist. He’s suffering, but I don’t know how to help him. Doctors don’t seek psychiatric care because mental illness is reportable to the medical board. He fears he’ll lose his license.” Her husband adds, “I was suicidal three months ago. On the edge. My wife and I are hoping to find answers here.”

Here, physicians, nurses, and medical students share their wounds and their wisdom—in community. We share new practice models, communication techniques, and strategies to care for ourselves—so we can care for our patients.

In four days, I witness more healing than in four years of med school. Once strangers, we’ve become family. Parting ways, the psychiatrist from Seattle thanks me again.

I didn’t know these doctors, but I know their despair. By speaking about my own pain, I validated their pain. By being vulnerable, I gave them the strength to be vulnerable too.

But mostly we healed each other by not being afraid to say the word suicide out loud.

Pamela Wible, M.D., is a family physician, author, and expert in physician suicide prevention. She offers biannual retreats for physicians struggling with burnout and depression. Contact her at idealmedicalcare.org.