Ever felt misjudged by a doctor? Or treated unfairly by a clinic or hospital? You may be a victim of patient profiling.

Patient profiling is the practice of regarding particular patients as more likely to have certain behaviors or illnesses based on their appearance, race, gender, financial status, or other observable characteristics. Profiling disproportionately impacts patients with chronic pain, mental illness, the uninsured, and patients of color. Like racial profiling by police, patient profiling by physicians is more common than you think.

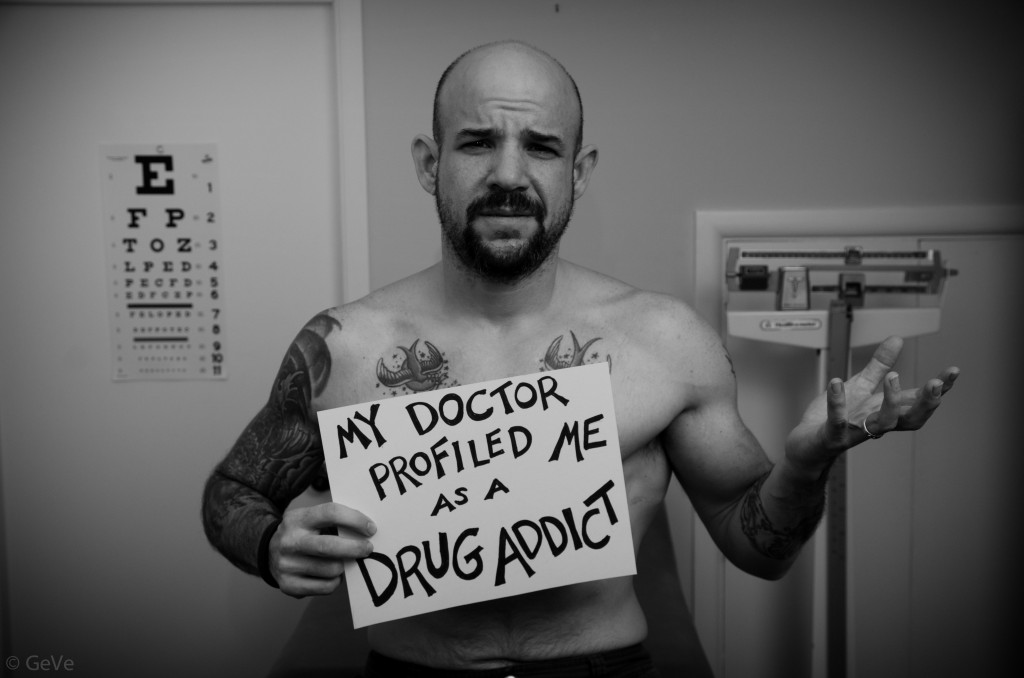

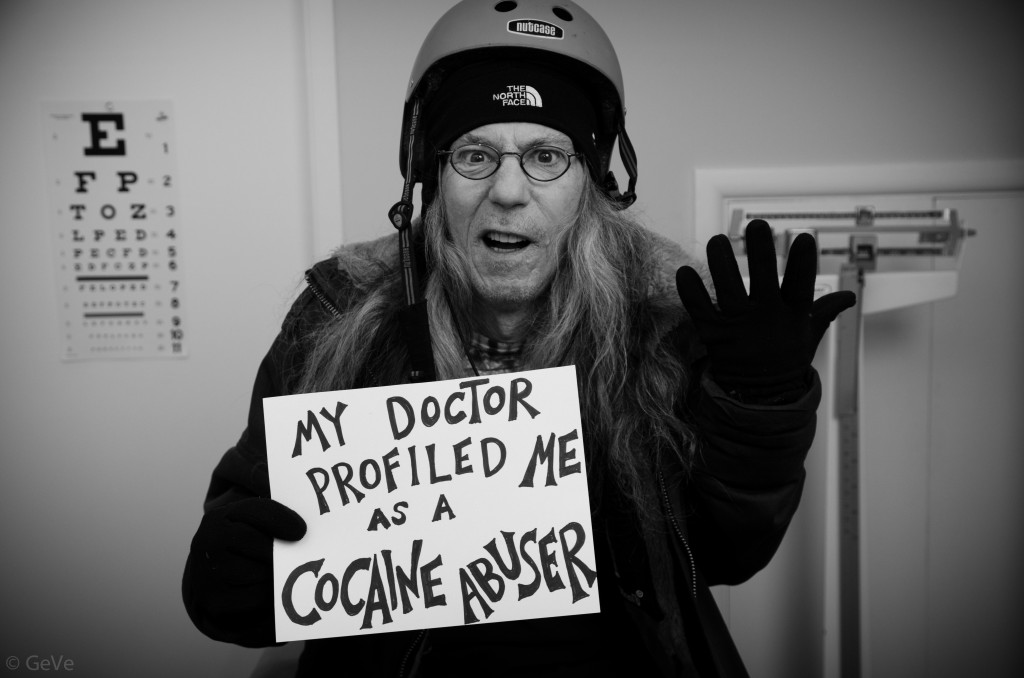

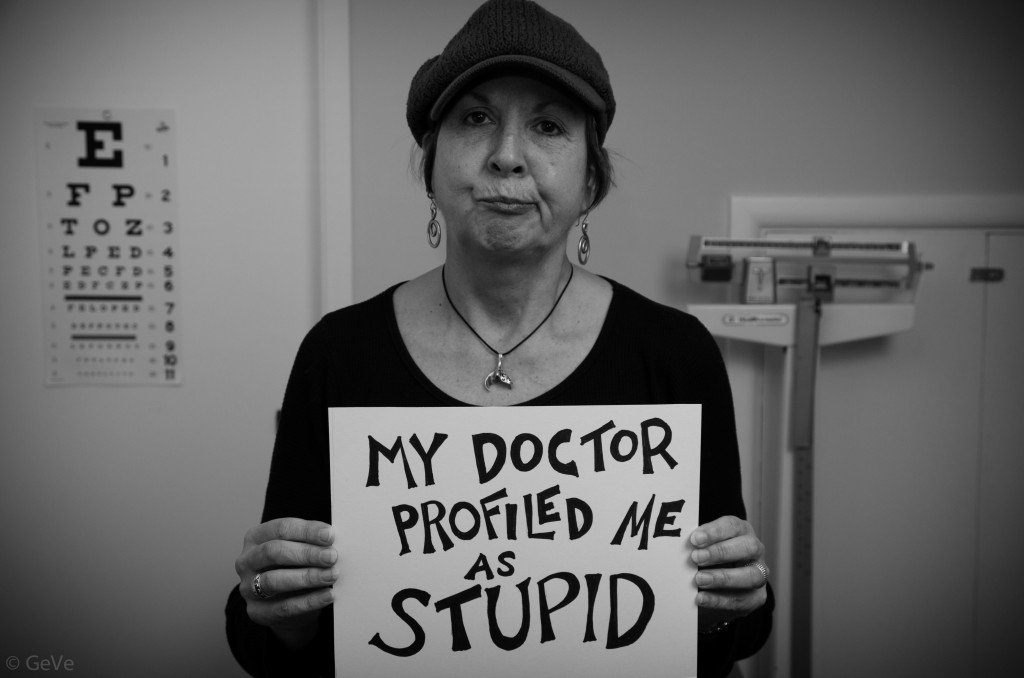

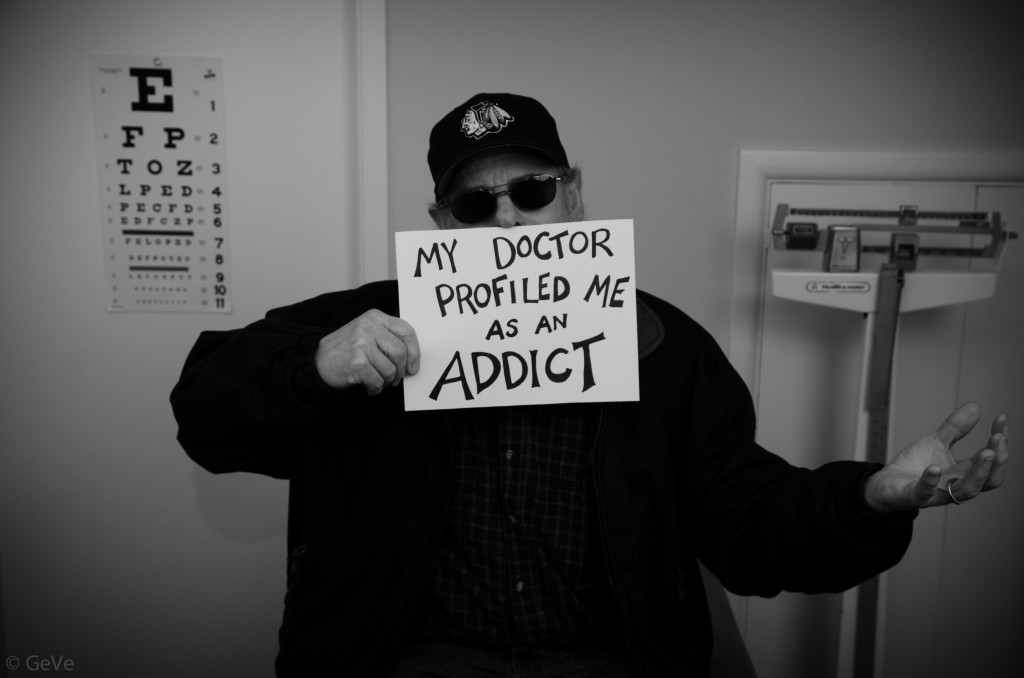

We rely on doctors to first do no harm–to safeguard our health–but profiling patients often leads to improper medical care, and distrust of physicians and the health care system, with potential lifelong consequences. For the first time, people share their stories:

“I was once denied pain meds after a fall off a 10-foot porch by the same doc who gave my pretty female friend pain meds after getting two stitches in her finger. I felt like my appearance had something to do with it.” ~ Jay Snider

“In 1986 I was in a motorcycle accident. I tore up my face on the road. I was taken to the ER and treated like crap because I had no insurance. They cauterized my facial wounds rather than stitch me up, and then dumped me on the sidewalk with amnesia. I still have distinct black scars; people think they’re tattoos. I went into collections and it took years to pay that one off. Six weeks ago, I fell while trimming a tree. When the ER found the insurance card in my wallet, I was treated like gold.” ~ James Cummings

“I was pressured by our doctor from my son’s birth all the way through grade school. I kept telling him no vaccines whatsoever, zero, nada. I was hassled, shamed, talked down to, and more. Not a fun experience, whatsoever. I was profiled as a bad mother.” ~ Sheri Ricker

“As a teen, I fractured my nose. Many sinus issues later, I consulted an ENT specialist. He insisted that I damaged my sinus passages by using cocaine. His assumptions caused me pain, humiliation, confusion, and anger. I repeatedly assured him that I wasn’t a user. Two surgeries later, my septum was removed. Afterwards, he was so cruel as to continue his tirade about my cocaine use. As the gauze was being removed from my nose, I fainted. When I was roused, he insisted that I leave immediately showing no concern about whether I could even make it home safely.” ~ Lonnie Stoner

“It was 1975. I was 23 and I’d been on the pill for 4 years, but I became concerned about potential negative side effects of long-term hormonal manipulation. So I researched other contraceptives and felt the diaphragm was the simplest and safest option for me. When I went to the county clinic to get fitted, I explained what I’d researched to the doctor. He scoffed at my concerns, urged me to stay on the pill, and disputed any potential negative consequences. He reminded me that taking a pill each day was SO much easier than having to be responsible for using the diaphragm properly. It was clear he thought I was too young and clueless to make this decision about my own reproductive health care. Although he tried to dissuade me from switching to a diaphragm, I insisted that’s what I wanted, and he finally fitted me for it. After he left the room, the nurse said, ‘Don’t worry, dear; it’s quite easy to use. I’ve been using one for years with no problems. It’s a good choice for you to make!’ It was clear she didn’t approve of his patronizing attitude either.” ~ Patsy Raney

“I injured my back at work. I couldn’t get time off, so my family doc prescribed pain meds so I could get through the day and Xanax for sleep. I returned every six months for two years and he always accused me of taking more than I was prescribed. He got progressively more rude and angry. I brought my wife with me to see if I was imagining it. She witnessed it too, so we searched for another doctor. I asked my new doctor to taper me off of the pain meds and Xanax so I could try medical marijuana instead. He was skeptical. He told me to go to the pain clinic. I’d gone there once before and was treated like a criminal. I didn’t want to go there! So he wrote up a contract that said I would agree to take pain meds and Xanax and I’d be drug tested monthly to make sure that I wasn’t using medical marijuana. When I told him I wouldn’t sign the contract, he told me to find another doctor. This was at a critical time when I needed real help and was worried about taking the meds for over two years.” ~ Carl Williams

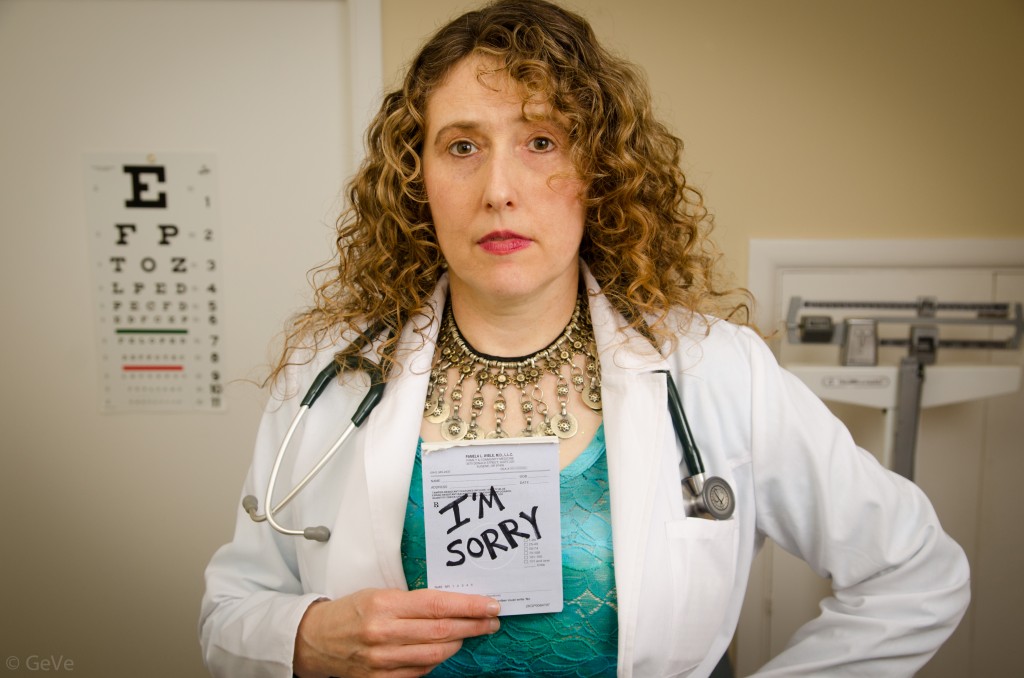

I’ve been a doctor for 20 years. I thought I’d seen it all. Drug addicted patients have altered my prescriptions, even forged my name. Patients have lied to me. Many haven’t followed my treatment plans. Some have died as a result. Still, I try to treat everyone fairly and with respect. But now I’m wondering, “Have I ever profiled a patient?” I bet I have. So on behalf of my colleagues and myself, I’ve got a message for any patient who has ever been misjudged or mistreated:

Comments are now closed. You can no longer leave a comment below.

Want ideal medical care? Here’s how you can get it.

Frustrated? Here’s 7 steps to get what you need from your doctor—fast!

Pamela Wible, M.D., is a family physician in Eugene, Oregon, where she founded the first ideal medical clinic designed entirely by patients. She is author of Pet Goats & Pap Smears. Watch her popular TEDx talk “How to get naked with your doctor.” Photos by GeVe.

Pamela Wible, M.D., is a family physician in Eugene, Oregon. She is author of

Pamela Wible, M.D., is a family physician in Eugene, Oregon. She is author of