Edited version of article reprinted by the Washington Post July 14, 2014

An obstetrician is found dead in his bathtub. Gunshot wound to the head. An anesthesiologist dies of an overdose in a hospital closet. A family doctor is hit by a train. He’s decapitated. An internist at a medical conference jumps from his hotel balcony to his death. All true stories.

What are patients to do?

When they call for appointments, patients are told they can’t see their doctor. Ever. The standard line: “Sorry, your doctor died suddenly.”

In most towns news spreads fast no matter how veiled the euphemisms. Trust me, when a physician under 50 is found dead, it’s suicide until proven otherwise.

The fact is nearly 1,000,000 Americans will lose their physicians to suicide this year.

So what’s the proper response? Deliver flowers to the clinic? Send a card to surviving family? As far as I know, physician suicide etiquette has never been discussed—anywhere.

Etiquette is defined as the customary code of polite behavior in society or among members of a particular profession or group. The customary way to deal with suicide is to ignore it. Physician suicide is rarely uttered aloud—even at the memorial service. We cry. We go home. And doctors keep dying.

I’ve been a doctor for 20 years. I’ve never lost a patient to suicide. I’ve lost only friends, colleagues, lovers–all male physicians. In the U. S. we lose over 400 physicians per year to suicide—the equivalent of an entire medical school gone!

What can we do? Let’s break the taboo.

Physician suicide is a triple taboo. Americans fear death. And suicide. Physician suicide—even worse. Yes, the people who are here to help us are dying by their own hands. And nobody is accurately tracking data. This is not popular dinner conversation. But it should be.

I’m a family physician born into a family of physicians. Raised in a morgue, I spent my childhood, peeking in on autopsies alongside Dad. I don’t fear death and I’m comfortable with suicide. So comfortable I spent six weeks as a suicidal physician myself. Even I was in denial—clueless about all the other physician suicides. Until our local pediatrician shot himself in the head. He was our town’s third physician suicide in over a year. At his memorial, people kept asking why. Then it hit me: Both men I dated in med school are dead. Brilliant physicians. Both died—by “accidental overdose.” Doctors don’t accidentally overdose. We dose drugs for a living.

Why are so many healers harming themselves? And when would be a good time to discuss this? During afternoon apéritifs? Discussing a decapitated doctor doesn’t pair well with any wine.

During a recent conference, I asked a room full of physicians two questions: “How many doctors have lost a colleague to suicide?” All hands shot up. “How many have considered suicide?” Except for one woman, all hands remained up, including mine. We take an oath to preserve life at all costs while secretly plotting our own deaths. Why?

I cover physician suicide in my TEDx talk. And Dr. Daniela Drake correctly identifies many of the reasons doctors suffer in her article gone viral, How Being a Doctor Became the Most Miserable Profession.

In his rebuttal to Drake, Sorry, being a doctor is still a great gig, Pediatrician Aaron Carroll calls the misery BS. He claims doctors are well-respected, well-remunerated, and they complain far more than they should. He predicts people will soon ignore doctors’ “cries of wolf.” To cry wolf is to complain about something when nothing is wrong, yet doctors suffer from depression, PTSD, and the highest suicide rate of any profession. Physician suicide etiquette rule #1: Never ignore doctors’ cries for help.

Bob Doherty of the American College of Physicians also downplays physician misery. His response is classic: when doctors complain, quickly shift conversations from misery to money—their astronomical salaries. But when a doctor is distressed how is an income graph by specialty helpful? It’s not.

I run an informal physician suicide hotline. Never once have I reminded doctors of their salary potential while they’re crying. Think doctors are cry babies? Read these physician suicide letters before dismissing doctors as well-paid whiners. Physician suicide etiquette rule #2: Avoid blaming and shaming.

After losing so many colleagues in town, I sought professional advice from our county’s medical society CEO, Candice Barr. She explains:

“The usual response is to create a committee, research the issue, gather best practices, decide to have a conference, wordsmith the title of the conference, spend a lot of money on a site, food, honorariums, fly in experts, and have ‘a conference.’ When nobody registers for the conference, beg, cajole and even mandate that they attend. Some people attend and hear statistics about how pervasive the ‘problem’ is and how physicians need to have more balance in their lives and take better care of themselves. Everybody calls it good, goes home, and the suicides continue. Or, the people who say they care about physicians do something else.”

So what works?

Our medical society established a Physician Wellness Program. The first in the nation to create a comprehensive program with free 24/7 access to psychologists skilled in physician mental health. Since April 2012, physicians have been able to access services without fear of breach of privacy; loss of privileges; or notification of licensing and credentialing bureaus. That works.

The key is to “do something meaningful, anything, keep people talking about it,” says Candice Barr. “The worst thing to do is nothing and go on to the next patient.”

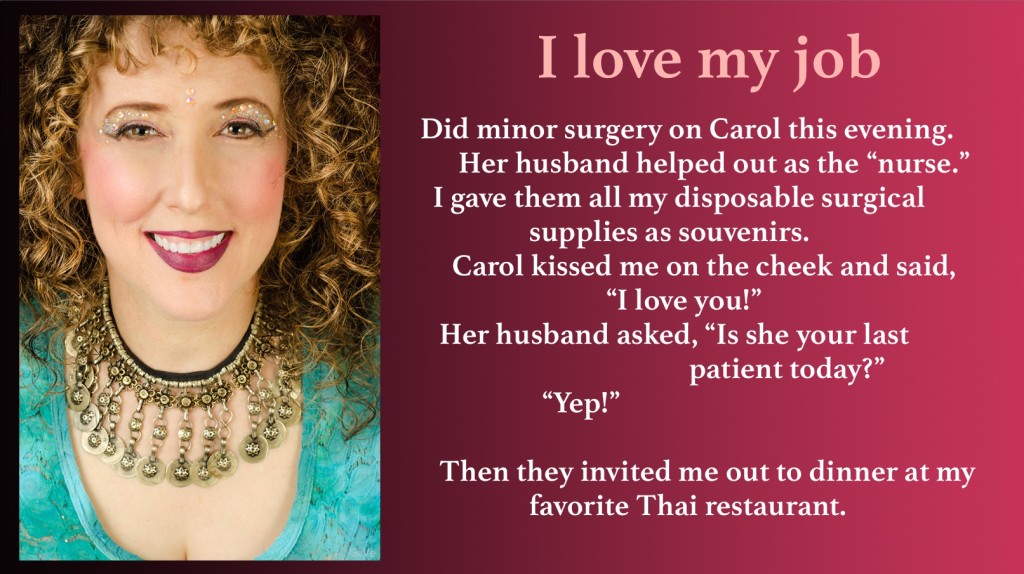

What’s most important is for doctors to know they are not alone. Doctors need permission to cry, to open up, to be emotional. There is a way out of the pain. And it’s not death. Physician suicide etiquette rule #3: Compassion and empathy work wonders. More than once a doctor has disclosed that a kind gesture by a patient has made life worth living again. So give your doctor a card, a flower, a hug. The life you save may save you.

Pamela Wible is an author and board certified family physician in Eugene, Oregon.

This blog was reprinted with author’s permission in The Washington Post.

* * *