An investigation is underway after a Chicago-area doctor is found dead—a suicide according to the medical examiner. What demands investigation is the callousness with which the this doctor’s death was reported by the media—and received by neighbors, many healthcare professionals themselves.

I’m alerted to the death initially by a Facebook friend: “Pamela, check this out!” Headline: Police: Doctor found dead near hospital in Berwyn. (Interesting side note: on 4/21 ABC news changed this headline to “Man found dead near hospital in Berwyn.”)

The facts:

On Thursday, April 16, a maintenance worker calls the police to request a well-being check on a tenant, Dr. Jon Azkue, a 54-year-old physician employed at MacNeal Hospital.

Police discover his decomposed body with suicide note surrounded by helium tanks. Mistaken as propane tanks, police call the bomb squad and evacuate the 4-story building which primarily houses healthcare professionals and medical businesses. How do his neighbors and colleagues respond?

“I was actually going to get some baby food,” says Jemin George. “My daughter is in one of the vehicles and it’s been almost three hours since she’s had something to eat.”

“It’s an inconvenience for the patients,” claims Riz Ahmed, an employee at Chicagoland Retinal Consultants, a clinic located in the building.

Anna Futya, clinic manager at the retinal clinic, is also frustrated by the inconvenience. “All the calls that are coming here—whether from patients or doctors—nobody is able to answer . . . “

Wait, I thought this news story was about Dr. Jon Azkue. The headline clearly states: “Doctor found dead near hospital in Berwyn.” So why is the focus on inconvenience to patients? How did the dead doctor get scrubbed from the story?

Who is Dr. Jon Azkue?

My online research reveals that Jon Azkue is a foreign medical graduate from Central University of Venezuela who was a senior internal medicine resident at MacNeal Hospital at the time of his death. He was just a few months away from graduating.

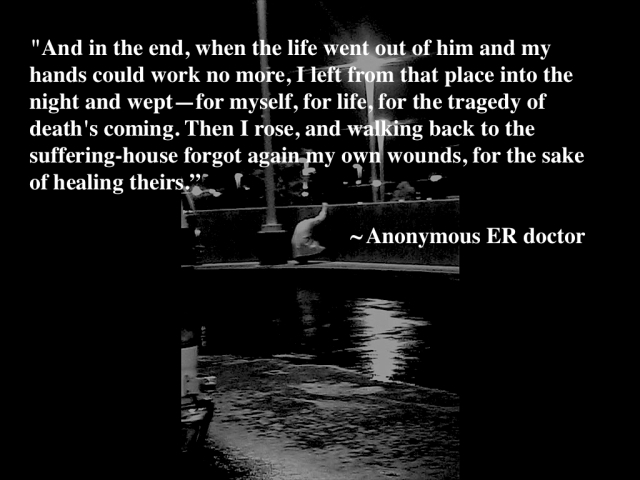

In this news report, Dr. Azkue is treated as if he is guilty of a crime. There is no expression of sadness for the loss of this doctor—presumably a man who spent his entire career caring for patients in at least two countries. In the comment section—amid jokes about terrorist plots and remarks about the selfishness of suicide—Doc T writes:

Wow. I’m appalled by the lack of sensitivity for the loss of life here. I myself am in residency and unless you live through it, you cannot begin to imagine the stress and sacrifices that we and our families endure—far greater than missed eye appointments. My condolences to his family and colleagues. The journalist and editor should be ashamed of the slant through which they allowed this ‘news’ to be delivered.

Facebook comments continue throughout the afternoon where Cailean Dakota MacColl, a premedical student, is equally appalled. “Hi Patient X, your doctor is selfish and died by suicide so they cannot do your eye exam today.”

Heather Springfield, another premedical student, chimes in:

I had the same line of thoughts. What a sad situation that a fellow human being who dedicated their life serving/helping others, is considered an inconvenience. It’s pretty damn ridiculous that society cries for its physicians to have an open doctor-patient relationship—to not be robots—but the moment a doctor shows their shared humanity, either they’re sued/abused/or die by suicide because they can’t take it anymore… etc. etc. What the hell is wrong with people? I wish, as a populous, we’d stop acting as if we live on separate planets when in fact, we share one planet. How hard is it to take a moment, and realize we lost a precious life to something preventable? It’s a damn shame, and my heart mourns such a loss…. This shouldn’t have happened. Shame on those residents, clinicians, and those who don’t take pause for what this is.

Physician suicide: more questions than answers

With his suicide confirmed, the real investigation must begin. Why did he die by suicide?

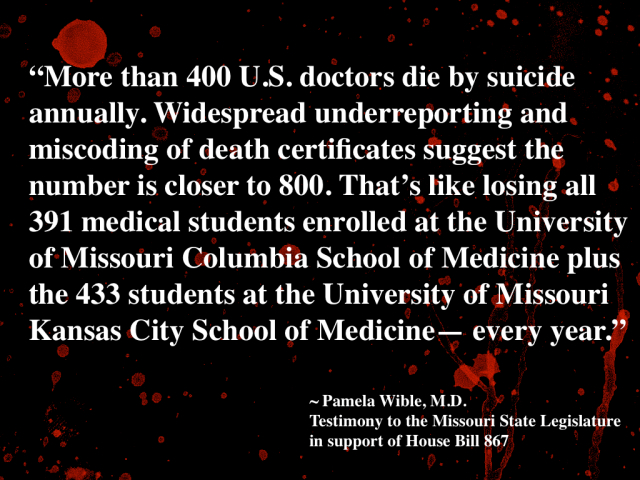

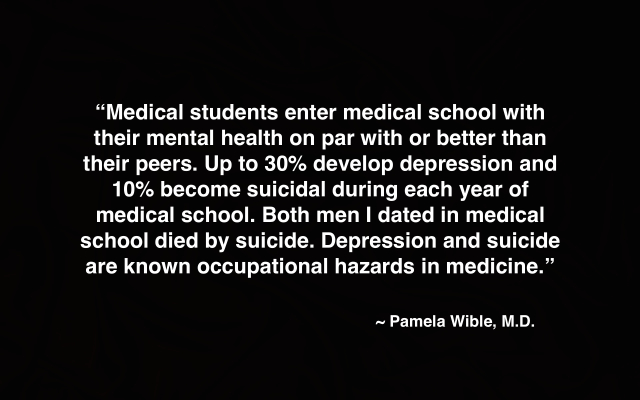

And why do we lose more than 400 U.S. physicians each year to suicide? Why are these suicides not investigated?

Like most suicided doctors, Dr. Jon Azkue left a note. Why are we not analyzing these suicide notes for common themes to prevent future physician deaths?

Sadly, we are unlikely to hear any more about Dr. Jon Azkue. We will not hear about the many patients he cared for, the lives that he saved. This is his 5 minutes of fame.

Pamela Pappas, MD, a psychiatrist writes:

Rest in Peace, Dr. Azkue. Being a resident at age 54 is not easy, and I’m wondering about his life and what led to this kind of end. No mention of family being notified before releasing this news to public, etc. Our culture (both medical and non-medical) apparently regards doctors as dispensable. Yes, of course patients are ‘inconvenienced’ when a doctor dies! Houston, we have a PROBLEM here, and we need serious remediation.

Why is this news story so unsympathetic to this deceased doctor?

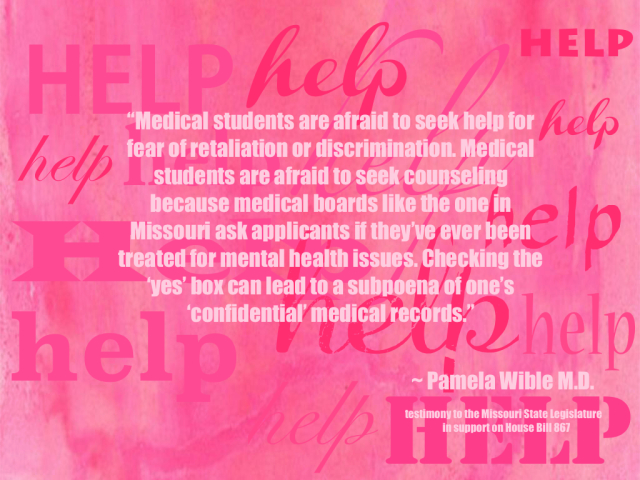

And why are clinics, hospitals, and medical schools so willing to sweep these deaths away—often with no debriefing for survivors. Why are physicians not receiving routine on-the-job mental health support for such a high-risk profession?

Georgia Jones, a Facebook friend, shares:

This is so sad. They [doctors] deserve to have therapy without being judged or the worry of losing their job. Schools need to start preparing students for what is to come, and have help in place if they become emotionally overwhelmed. It’s so sad that this is still happening. Doctors are human beings, like us. Start treating them as such. They’re not machines! They have emotions, and believe it or not, the death of their patients DOES affect them!! Give them a break! R.I.P. Dr. Azkue. I’m sorry it came to this.

Here’s the truth: until we investigate why this doctor died by suicide, we will continue to lose more doctors. Maybe if we took a sincere interest in Dr. Azkue’s death, we could prevent the next one.

Incidentally, Kim Aaronson, a chiropractor in Chicago, adds:

Here’s another note of interest, a local chef here in Chicago died by suicide on Tuesday of this week. It has remained in the news every day. (even covered in this NYT article) The doctor’s suicide has not even been mentioned. There is clearly uneven coverage going on here…. The FB comments show the kind of empathy the press should have shown…. You are so right on, a doctor dies and it seems that no one cares at all….

Pamela Wible, M.D., reports on human rights violations in medicine. She is the author of Physician Suicide Letters—Answered. Struggling? Need help? Contact Dr. Wible.