Most physicians appear self-assured. Yet even doctors have self-doubts. But who wants an insecure physician? A confident doctor inspires confidence in patients. So how do physicians cope with their hidden insecurities?

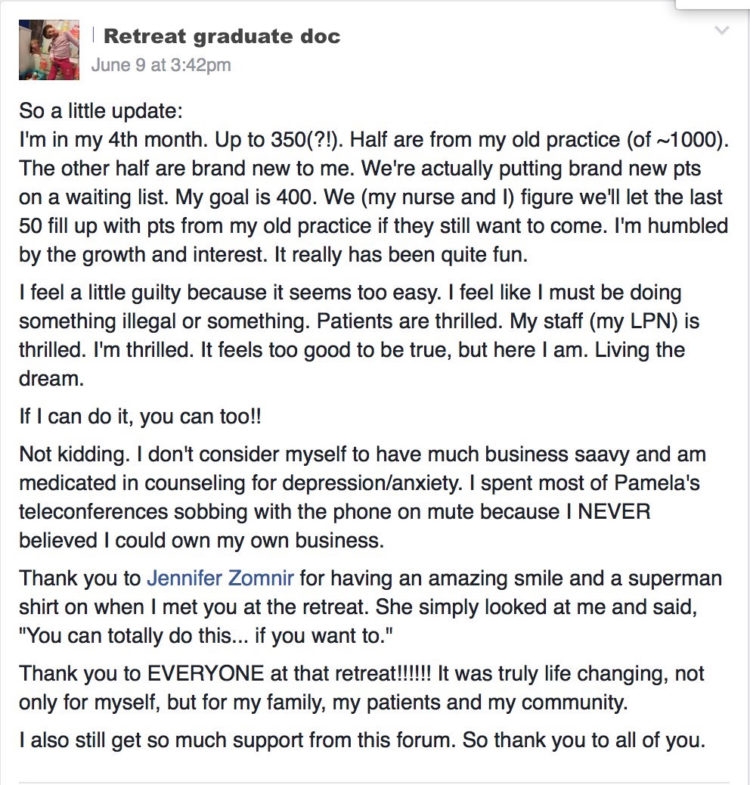

I actually had no idea that doctors lacked self-confidence until twelve years ago when I began teaching physician business strategies to succeed in independent practice. When I ask physicians what they need most, self-confidence always ranks near the top. One doc told me, “I want my confidence back. Right now I don’t know what to think. I feel like I’ve been second guessed at every turn by administrators, ‘evidence-based medicine,’ peer reviews, and patients. I’m beaten down.”

Physicians are highly intelligent. We enter med school as high achievers, top of our class—even valedictorians. We’ve got confidence. So where did it go? To investigate, I asked 189 medical students: “How has medical school impacted your overall self-confidence and/or self-esteem?” Of the respondents, 42% reported an increase, 50% reported a decrease, and 8% noted no change.

Why do half of all medical students graduate with less self-confidence while 42% have more? I asked those I surveyed to share their thoughts. While some claim all the new knowledge and skill increased their self-confidence, others like Lynn share, “Med school completely destroyed my self-confidence. I am constantly feeling stupid and worried about failing out.”

The most disturbing report comes from Claire: “I imagine all med schools are difficult, but mine is sadistic (a direct quote from our school counselor). My school is notorious for failing students—10-20% of every class every semester. It doesn’t matter if your brother just died, If you’re .01% away from passing any class, you’re dismissed. No makeup tests. Before med school, I was a 3.98 student. Today I’m a C+. Talk about deflating. I’ve gone to every department to figure out how to bring my grades up, but the response is, ‘you’re not smart enough.’ I know that’s not true, but it hurts that my school doesn’t think I belong here (but they’re happy to take my money). All this crap has culminated in a deep depression. I’ve developed test anxiety that paralyzes me during exams. The only help I’ve received is antidepressants. I constantly doubt myself. I even struggle to interact with my husband and son. I feel like an idiot for coming here—and even worse for dragging my family into this $200,000 mess without knowing if I’ll ever pay it off. I worry that I’ll never be able to practice medicine. It’s enough to drive anyone mad. Worst of all, I’ve become cocky just to deal with all the assholes that I’m surrounded by, but my confidence is down the toilet.”

Often students report self-confidence being “destroyed in the didactic years” and “built back up in the clinical years” as reported by Oliver: “Medical school locked me in a study dungeon. I floundered, fell further behind, and felt intimidated to ask for help. I had gone from the top 10% at my undergrad to the bottom and felt completely helpless. One professor suggested I wouldn’t make it as a doctor. The school provided CYA-type meetings, but didn’t give actual help. Then I excelled in clinical rotations. I’m back in control of my world. If I continue on this trajectory, I’ll be more confident than ever, but that’s because I survived nearly being destroyed. The system isn’t set up to make you feel good about yourself, and some of my classmates are coming out ready to pay their debts and then retire from medicine.”

Post traumatic student disorder?

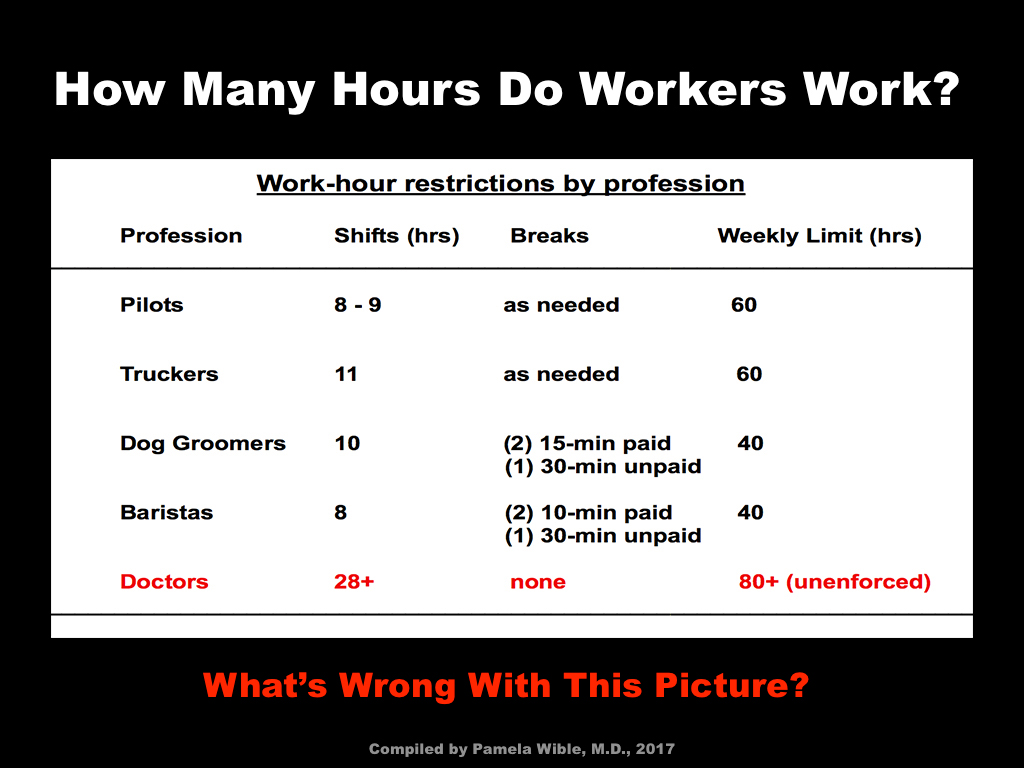

What are the long-term effects of medical training on physician self-confidence? I asked 1,123 physicians the same question: “How did medical school and residency impact your overall self-confidence and/or self-esteem?” Of those who responded, 46% reported an increase, 46% reported a decrease, and 8% noted no change. Of those who reported a decrease, their experiences often led to chronic mental health issues, including PTSD, depression, anxiety—even suicide among their classmates.

“I was near death when I departed my residency. I’ve personally known three very compassionate, competent residents who took their own lives while mired in their darkness and disillusion during my training. Medical school was a devastation in my life and forever changed not only my career path, but also my personal health, relationships, and my perspective on the medical field,” reports Laurel, who is no longer practicing medicine.

“I had emotional whiplash in residency,” reports Rochelle, a solo family physician, “Attendings would gang up on one resident and say, ‘You’re destined to fail. You’re lazy.’ I received scathing reviews about ‘attitude’ and ‘difficulty with authority.’ I remember standing in my bedroom having these crazy panic attacks and thinking I could not go on. They stopped picking on me after a few months and picked on someone else, but I’d see it and it would make me sick. I personally know of one resident in every class who became suicidal while I was there. One had a car ‘accident’ and died going off a cliff but we all wondered if that was actually an accident.”

Abusive preceptors who use fear-based teaching often undermined students’ education. Renee, an obstetrician shares, “It would be many years before I recovered from the fear of what was the motive behind a question. The sad thing is that I now realize most people are not coming at you in attack mode, and I had missed out on a lot of opportunities. However, most of my colleagues, it seems to me, have never recovered. Physicians do not befriend one another. They are either arrogant and don’t need friends, or distrusting and will never let you in.”

“I entered medical school so very confident in myself and that was beaten out of me.” confirms Amelia, who is now applying to residency. “I was repeatedly told I was stupid. I was threatened with being sent away from my 6-month-old without warning for the sake of medical school. Motherhood was not supposed to be a priority. I was labelled ‘too emotional’ as I burst into tears after being bullied. I begged for help with my anxiety and was flatly denied any assistance.”

Many female physicians also survived sexual harassment. Steve, an internist, confirms, “My residency director used to punish females who wouldn’t put out—medical school or residency, married or single. For us males, it wasn’t that bad.”

“Our program director suggested we get slave T-shirts for the group.” according to Melissa, an internist, “In my residency mailbox I even received nasty anonymous you’re too fat notes, ads for diet pills attached.”

Medicine often endorses a culture of groupthink that discourages dissent, discussion, and individuality. Jenny, an internist, recalls, “The further I progressed in my training, despite acquisition of more skills and knowledge, the more fearful I became. Criticism in various forms never ended. The further my confidence dwindled and I became more outwardly hesitant (despite feeling inwardly confident about my answer or plan) the more colleagues questioned my decisions. This may have to do with my almost extreme introversion and difficulty asserting myself. I watched colleagues often act and speak very confidently even when I knew they didn’t totally know what they were talking about. I never mastered this skill of acting confident even when in doubt. I felt it was disingenuous. My true opinions on what was best for a patient were frequently different from the group. I became afraid of expressing myself, even when I knew I was absolutely correct. Before medical school I was never afraid to be a dissenting voice, but I learned in residency that it did not matter if I was correct—disagreeing with someone higher up than myself, even if in the interest of patient safety, was not in my best interest.”

Ann, a neurologist, summarizes, “One needs a trust fund of self-esteem in order to survive medical school and residency.”

Insider secrets to physician self-confidence

For every physician who reports a decline in self-esteem and/or self-confidence in medical training, another reports an increase. What’s the secret to thriving in medical training? Just getting into med school and residency is a confidence builder for most. After graduating, many physicians like my mom (a psychiatrist) believe they can survive anything. Physicians fared best in progressive schools that promoted student health and medical humanities. Having a good support system strengthens students’ self-worth as does a welcoming atmosphere of mutual respect and open communication. “My medical school was wonderful,” Rochelle explains. “We were called ‘young doctors’ and generally allowed to question things. We were encouraged to report harassment and they told us, ‘You are all the brightest and the best and you are going to go on to amazing things.’”

Throughout my research I’ve become aware of the predatory nature of some medical schools. So what can be done now to help the next generation of medical students and physicians? Let’s replicate what’s working. Here’s what the most progressive medical training programs already do:

1) Provide inspiring professors rather than cynical and abusive ones.

2) Create a collegial atmosphere in which physicians and students befriend one another.

3) Offer non-punitive academic support to all students.

4) Discourage all forms of harassment on campus with anonymous reporting.

5) Avoid fear-based teaching and pimping.

6) Provide accessible and confidential mental health care.

7) Uphold the human rights of their students.

What’s the self-esteem quick fix?

Medical training will become more humane. Yet systems are slow to change. What can med students and residents do now? Linda, a family physician, reports, “I think self-esteem is a more fundamental issue that is pretty set once you’ve reached med school and residency. My self-esteem is generally good, which is why I refuse to put up with this abusive medical system. I don’t let other people abuse me and I won’t allow this broken system to abuse me either.” I agree with Linda’s tactic. Salvage the self-confidence you have now and refuse to be abused.

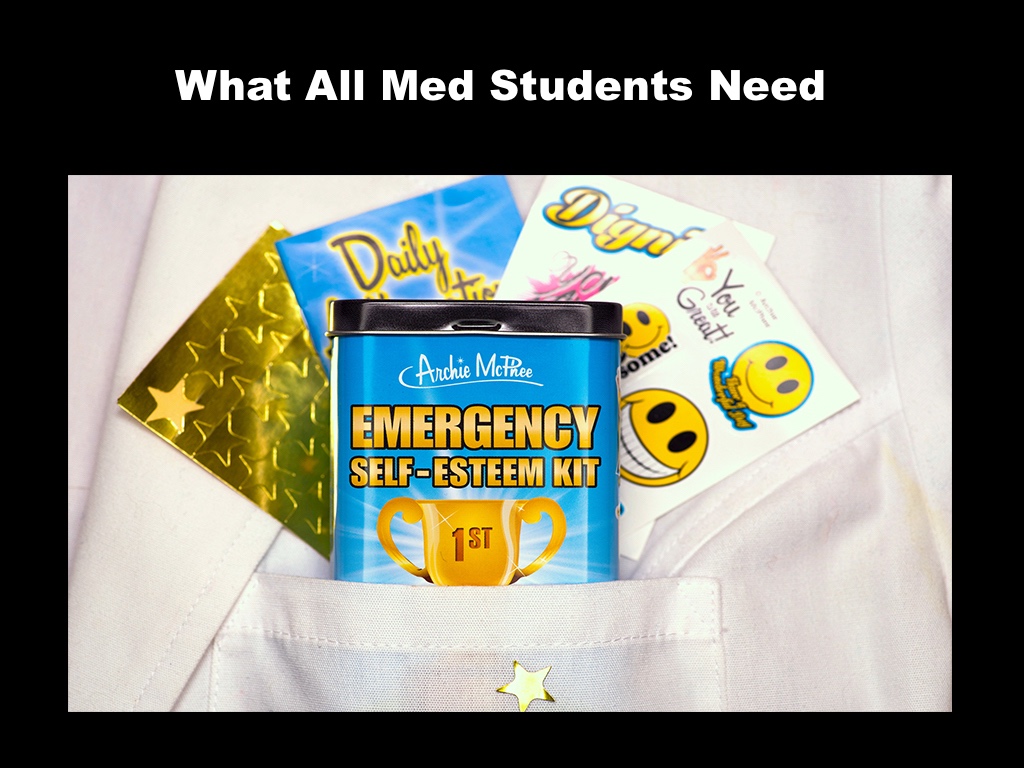

Oh, and here’s something all med schools should hand out during orientation: an emergency self-esteem kit. This cool little kit contains a mirror on the back with a message “you are awesome.” Inside there’s a trophy for first place in specialness, self-esteem building stickers, a book of daily affirmations, and gold stars you can give yourself. Nobody makes it through medical training without some bumps and bruises to one’s self-worth from a challenging case or a cynical attending. I would have loved to have one of these emergency kits during med school. In fact, I just handed some out to a local residency program last week.

Pamela Wible, M.D., is a family physician who reports on human rights violations in medicine. View her TEMED talk Why doctors kill themselves. She is author of Physician Suicide Letters—Answered. Attend her upcoming retreat for medical students & physicians. For scholarships, contact Dr. Wible.