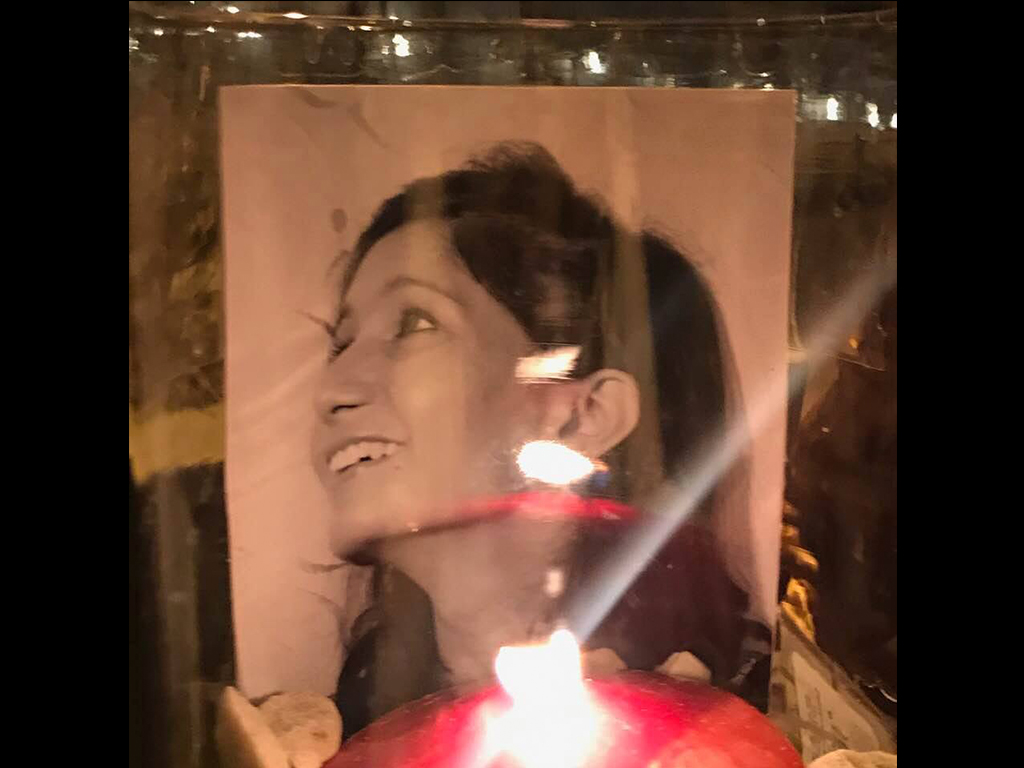

I spent last weekend in NYC. I didn’t go to a Broadway Show. I didn’t go shopping at Tiffany’s on 5th Avenue. I didn’t dine at any fine restaurants. Instead, I sat at 515 W. 59th—the location of the most recent Sinai suicide.

A new attending physician—just four days into her position at the hospital—walked across the street to a building that houses nearly 500 doctors. At 3:30 in the afternoon she stood on the roof of the 33-story high rise in her white coat. Then stepped off the ledge.

I planted myself on the pavement where she died. I brought flowers and candles. I bought her Valentine’s Day hearts full of truffles. I arranged the beautiful bouquets from all across the country. And I eulogized her—and the others who died in the same spot.

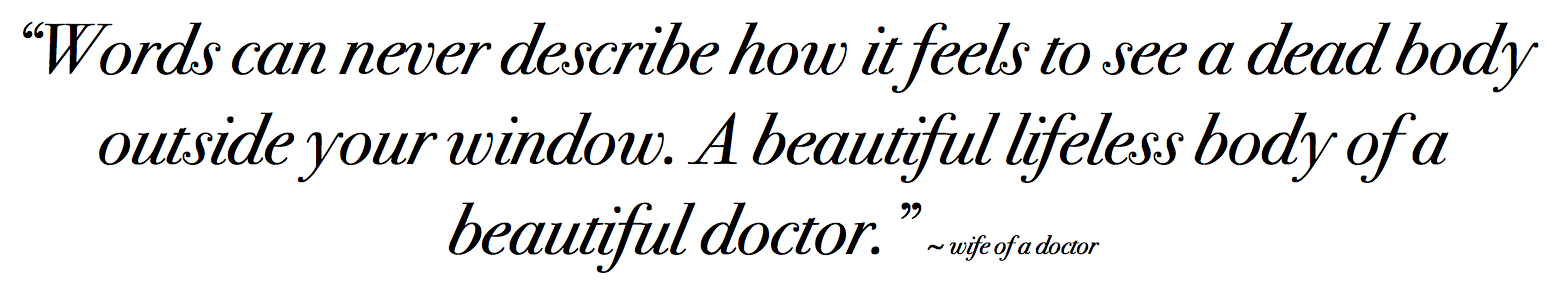

I learned of her suicide an hour after she died from the wife of a physician—a busy mom with three little kids who was begging me for help. She broke away from her usual routine—baking brownies and reading bedtime stories—to snap this photo of the scene outside her window. Then she shared this:

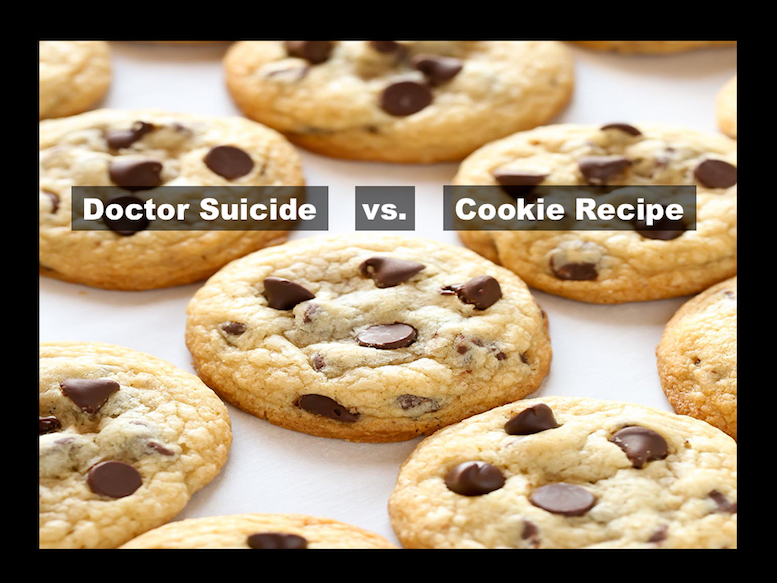

“I posted a heartfelt note on a private Facebook group called ‘Lives of Doctors Wives’ with over 11,000 members with the KevinMD article and your own. Many women saw it and fiercely responded in rage about what happened and very empathetic to what I wrote and wanted justice for this doctor too. But get this—the admin on the group DELETES my post! Apparently you can’t post a ‘call to action.’ I’m so upset—this group only talks about cookie recipes. WTF. If you’re going to have a group called ‘Lives of Doctors Wives’ we need to talk about these issues, so much more important than trading moving tips, come on. Anyways fortunately SO many women posted separately with just a link to your articles and so the conversation is still going. They have so much praise for you in all of the comments. I was going to screen shot and send them to you till they frickin’ deleted my post.”

What was the call to action? To buy flowers for a doctor’s memorial? To bring a candle to a vigil? To discuss doctor suicide?

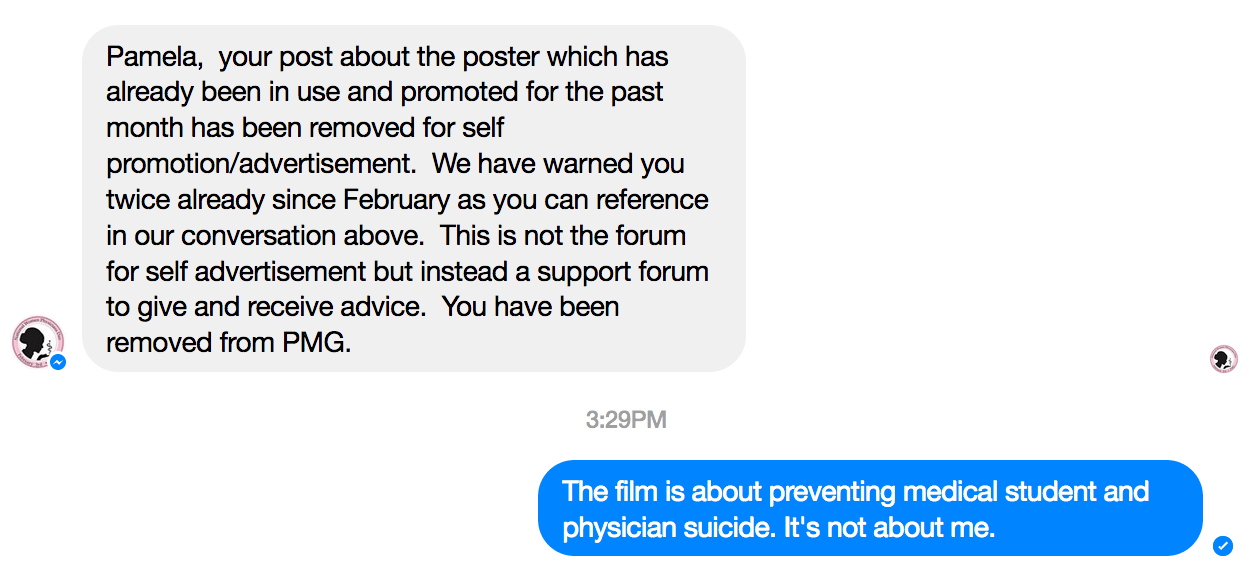

I’m no stranger to physician suicide censorship.

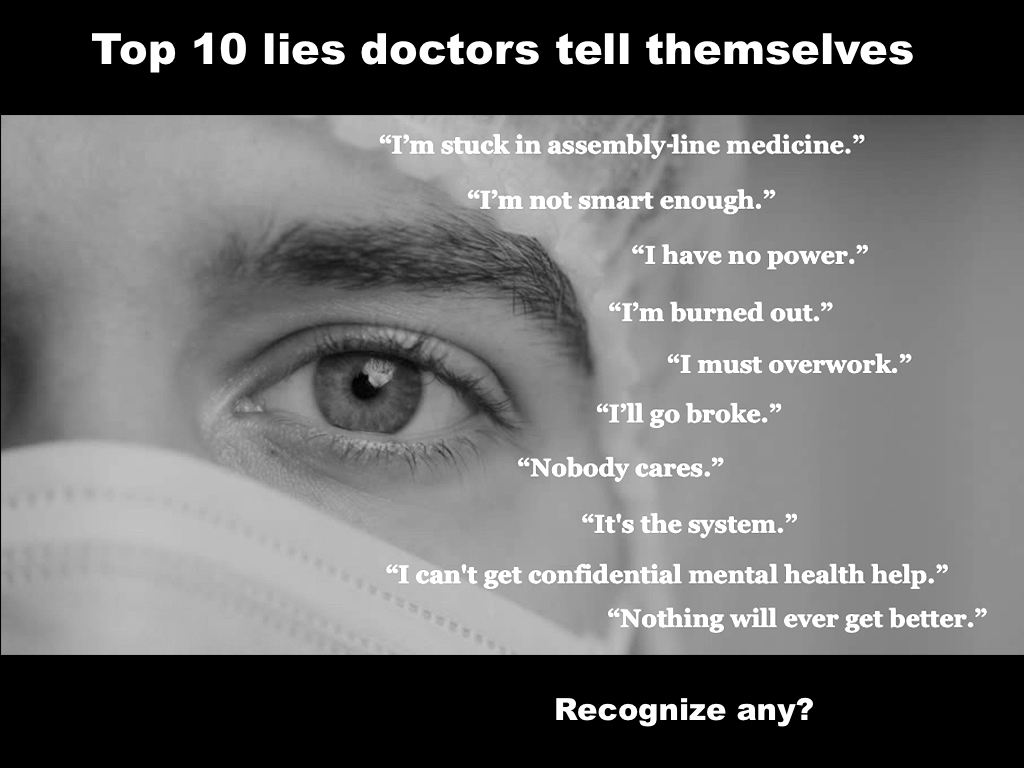

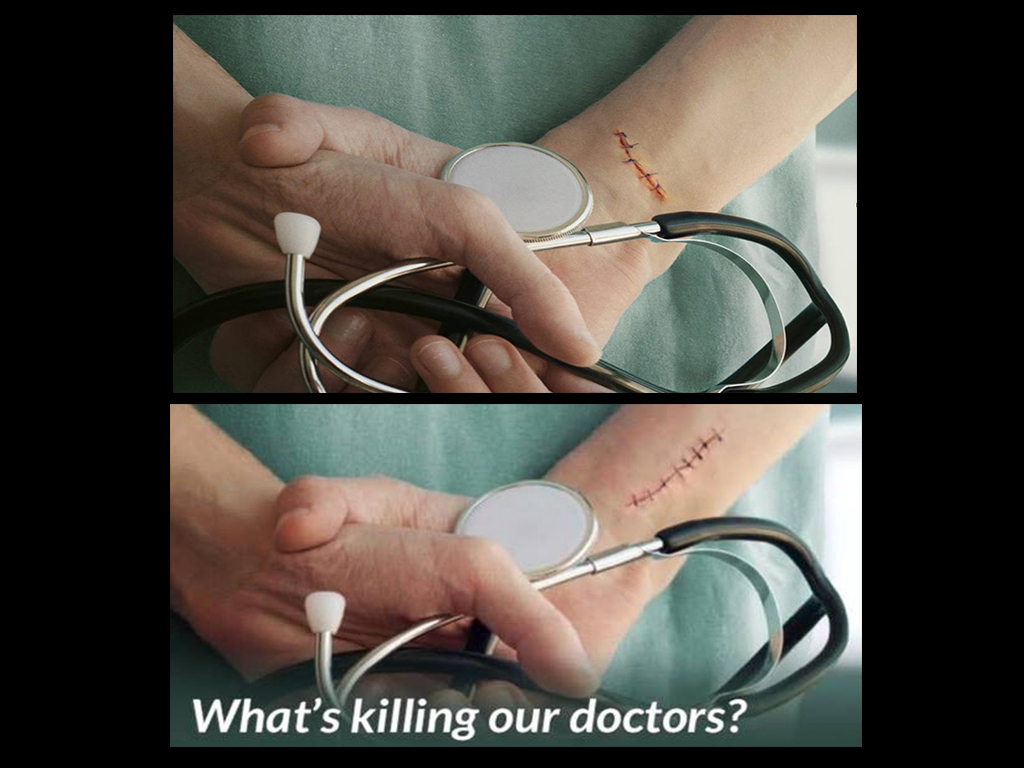

In July of 2017, my post was deleted and I was banned from Physician Mom’s Group—a Facebook group with > 60,000 female physicians who discuss everything from the most challenging medical cases to new business ventures. Women docs give and receive advice on book covers, clothing line launches, and, of course, cookie recipes. Here’s what I wrote verbatim about the forthcoming film by Robyn Symon—an Emmy winning filmmaker who has dedicated the last 3 years of her life to addressing our doctor suicide crisis.

“Morbid post. Need help. We are designing film poster for Do No Harm film to prevent doc suicides and we’ve got an internal dispute about BEST angle for slitting one’s arteries for suicide. Here are two versions. Definitely appreciate any help. Specifically what angle would a doctor use? Thoughts?”

In the midst of a lively conversation with nearly 150 comments my post was deleted and I was banned from the site.

On 11/8/14 after medical students shared that my blog “How to graduate medical school without killing yourself” actually saved their lives, I shared it on the Student Doctor Network. I had previously attempted to share information on medical student suicide prevention. Apparently I’m not allowed to post blogs (or excerpts from my blogs) on doctor suicide—even if information can prevent suicides of their own members on Student Doctor Network. So I was banned.

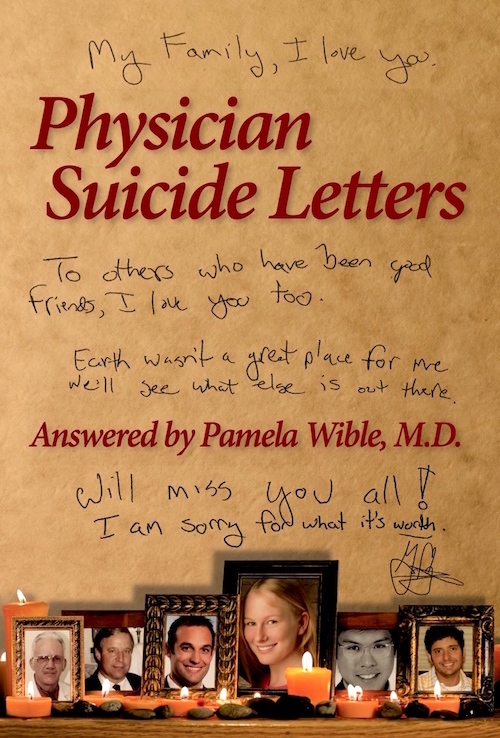

Then my book was banned from an anesthesia department. After the suicide of a former internal medicine resident and an anesthesiology resident at a prominent US hospital (in which no grief counseling was offered) an attending purchased 6 copies of my book Physician Suicide Letters—Answered to distribute to her residents. She was summoned to the office of the division chief who stole the books she had left for residents in the anesthesia workroom and told she was not to distribute these books to the residents.

After being invited by the AMA to deliver my TEDMED talk, I was disinvited shortly before the event because they were “uncomfortable” with the topic of physician suicide.

I write and speak on many topics. Somehow only the doctor suicide content keeps getting deleted and banned.

I am eternally grateful to those who have stood by me during the past 5 years in my quest to save doctors’ lives— Kevin Pho MD, The Washington Post, Medscape and TEDMED. Thank you for never censoring lifesaving content from your sites.

Censorship and secrecy will not solve our suicide crisis.

For those who are still uncomfortable with the truth, try a few of these:

Want the ultimate in free speech? Liberate yourself from assembly-line medicine. Launch your own practice. Learn how to be the doctor you always imagined at our upcoming seminar. Can’t wait? Join the Fast track.

Email #2

Email #2