Pamela Wible: I’m interviewing a really great friend of mine today, Daniel Herzberg. So Daniel, tell us a little bit about yourself and what kind of work you do.

Daniel Herzberg: I’ve had a long career doing educational consulting. I’ve also been integrating that with business consulting. On the educational side, I’ve been doing this kind of work for twenty-five years. I’ve met with over 8,000 kids, young adults, and basically helped them get into the top universities. I teach every junior high and high school subject and have kids who have gotten admission into every Ivy League school in the country. I’ve seen a lot in the course of teaching all these different subjects and doing SAT and ACT prep and writing college essays. Every possible path kids have gone down and also the struggles they’ve hit as they’ve been trying to get there, too.

Pamela Wible: You come across people at the earliest stages in their careers as they’re heading towards the field of medicine. So these young, premedical students with their dreams on fire, wanting to be neurosurgeons and they’re fifteen years old. And others that are pressured into going into medicine by their family who maybe are not quite right for it. Share a little bit about what you notice, how you got into helping these premed students in particular.

Daniel Herzberg: First I just want to mention that in terms of my personal path, I was premed. One of my degrees is in general science with minors in chemistry and biology, and I was on a path to go to medicine. It’s funny because we actually met right when I was at the point of deciding. You’d just finished your residency and I was just getting ready to go to med school. You were very influential for me in not going to med school. I’d been talking to a lot of doctors, a lot of people in the healthcare field, about medicine, and you were one of them. I probably interviewed about thirty different healthcare professionals before I realized that for me it wasn’t the right fit.

One of the things I’ve noticed with a lot of teenagers and their families is that oftentimes it makes parents very proud to hear that their kids are going to go into med school, that they’re going to become a cardiac surgeon or they’re going to do something noble like going into medicine. And it is a very noble field to go into. I’ll often ask them, “So when did you decide to become a cardiac surgeon?” And the kids will say, “Oh, I’ve wanted to my whole life.” And I go, “Well, how old were you when you decided?” And they go, “Well, I guess since I was seven.” And I’ll ask them things about the field, if they understand stuff about it. I’ll say, for example, “Do you know how long it takes to become a cardiac surgeon?” And they go, “What do you mean?” I go, “Do you know how many years it takes to become a cardiac surgeon?” And they’ll say, “No, not really.” And I’ll say, “Let’s just count it out.”

It’s four years of premed, then you have a transition year between premed and med school, or maybe you just go straight through into med school, but a lot of people do take a year off between the two to apply and catch their breath before they go on in the training. Four years of med school, three to seven years of residency depending on the specialty you go into. And after all that time you’ve got a lot of debt to pay off. Most doctors, if they’re lucky, finish that process when they’re twenty-seven or twenty-eight, and some are later than that, and then they’ve got debt to pay off. I said, “Have you thought about how long it takes to become a doctor?” And they’re like, “No.” So I’ll just point out to them that currently their commitment, their current career path, was decided when they were seven years old without having an informed decision about what they’re going towards. And the parents are, on the one hand, very anxious about this conversation, but at the same time kind of relieved, because at some point they need to be in reality about what they’re actually talking about and what the path looks like.

Pamela Wible: Wow. I really wish you could speak with all premed students before they get going. Because I end up interfacing with them once they’re depressed, anxious, suicidal, and some of them really are not meant to go into medicine, but they’re already in their first year of medical school, you know?

Daniel Herzberg: Yeah, and it’s hard to pull out of that. There’s the work itself that goes into all the study and all the commitment and sacrifice and hours that goes into doing all that study. I think the hardest part for teenagers and for premed students and for med students is the shift in identity, because many times they’ve gotten so caught up in seeing themselves as somebody who is a doctor, who will become a doctor, and every time they mention it to somebody, they get all kinds of recognition and approval and reinforcement that that’s a great thing to become. In the Jewish community, for example, if you mention you’ll be a doctor, your parent’s heart just swells. They just kvell that “Oh, my child’s going to go become a doctor.” It’s hard sometimes to step off of that track and think, “Well, okay, that’s a role that I could pursue. Is that me? Is that the only thing I could do that I’d be happy with?”

My sister is a physician herself. When I was going through premed coursework she said, “Is there anything you’d be happy doing in your life that was not medicine?” I listed about ten different things I’d be happy doing, and she said, “Then why don’t you pursue those other things?” Because if you do medicine, it’s kind of an all-or-nothing proposition. It’s binary. You’re either in it 100% or you’re not. That kind of opened my mind. It got me thinking more about other options and realized that maybe it wasn’t the right thing for me.

Pamela Wible: That’s extremely smart, and I would echo that advice—if there’s anything else that you would love to do, please pursue it because you will have no time to pursue anything else even as a hobby in some specialties. You will be very busy, and you may not even have time to procreate and have a family of your own. If you have personal life objectives, those are going to be delayed until you’re close to forty years old for some people.

Daniel Herzberg: When I was going through premed, I was living in Oregon, going to the University of Oregon, and at the time I was also tutoring. I was tutoring all these different families. I’d say probably about half of the families that I worked with one of the parents was a physician. So I had a chance to talk with a lot of these folks too, and what I noticed in general was, in all but one cases, there was an extreme imbalance, where there was just so much time and energy that went into working at the hospital and doing things that were medically related that they were often absent around the kids. They weren’t as engaged in their relationship with their partner. I saw several families actually divorce during that period because there was just not a connection. The physician parent wasn’t really engaged.

Pamela Wible: That’s fascinating, because at my retreats, I’ve had physicians attend who are children of physician parents. I remember one in particular still had so much anger in his mid-thirties for his father—a surgeon who was never around. I do intuit that some of these people often will pursue the specialty of their parent just to get close to the person they lost in their childhood. Isn’t that interesting?

Daniel Herzberg: Wow. Yeah, that’s extreme. I’ve seen that in other fields too, but in medicine, it is almost like there’s this attempt to solve the mystery of why the parents are not there.

Pamela Wible: I can definitely say I’m in medicine for the right reason, and I do feel like I was born to be a healer in this lifetime. But I will say that to bond with my father (a physician) I trailing around with him at work—that’s where I had most of my bonding with my father. I don’t really remember a lot of bonding with him outside of a professional setting in the hospital. Now you can’t really have your kids tag along in a hospital setting.

Daniel Herzberg: A generation or two ago, it used to be a doctor had their own typical physician practice, maybe. They could have a private practice or they could have a group practice of some kind that allowed them a lot of flexibility in terms of how and when they worked. It wasn’t as institutionalized as it is now. It’s not the same field anymore. Technology has increased. There’s the need to be constantly learning new things. You’re always keeping up on the treadmill with what’s the latest and greatest new technology that’s out there. And in the institutional environment most doctors have been more or less brought into hospitals for the most part.

Pamela Wible: I’m really curious to hear why you decided not to continue your medical education. You interviewed all these doctors. What did you learn? And how was I pivotal in this decision?

Daniel Herzberg: First of all, what I sensed when we talked was just the stress that you were under and the frustration that you had. You talked a lot about some of the stuff that you went through in the course of your own medical training, like having to dissect animals and stuff like that, that kind of threw me off. I was like, “Wow, there’s some ethical stuff here that people have to really make peace with if they’re going to go through this training.” I talked to a lot of doctors and healthcare folks. I talked to allopaths, I talked to osteopaths, I talked to chiropractors, I talked to homeopaths, I talked to acupuncturists, physical therapists, occupational therapists. I talked to just an array of professionals and academics. Nurses, nurse practitioners, physicians’ assistants, phlebotomists. Anybody who I could take time to interview and find out more of what they did in the medical field.

One of the challenging things for me was, I just didn’t find anybody I actually wanted to emulate. It wasn’t just the professional side, it was the aspect of how they were living. I had the sense that everyone felt kind of stressed out and a bit compromised. The one major exception, I would say, is the physicians’ assistants generally seemed more content. But there was just a lot of stress that I was seeing in the medical field. I remember at one point I was shadowing a gastroenterologist and he was introduced to me as a really wonderful internist who allowed me to even watch procedures and stuff like that, and talk to him about what he dealt with as a physician.

One of the reasons why I was introduced to him was because he was really interested in alternative medicine and even specifically acupuncture. I asked him about his interests, and he goes, “I’m really going to get into studying acupuncture as soon as I can.” I said, “When’s that going to happen?” And he pointed over to a stack of journals that he had on the floor that was two feet high. I said, “What’s that?” He goes, “Those are the gastroenterology journals that I have to read through first.” I said, “You have to read all of those before you start studying acupuncture?” And he said, “Yeah.” I said, “So, how long has that stack been there?” And he goes, “About three years.” “Has it always been about that height?” He goes, “Actually, yeah.” And I just realized he was kind of deluding himself into believing that he was going to ever catch up with that. The idea of having to read two feet of academic journals to keep up with what’s going on in the field before you get to do what he really wanted to do just seemed kind of sad to me, that he wouldn’t be able to do that.

I also got my certified nursing assistant license and I was doing a little bit of work in the hospital, and I was just shadowing doctors and going in and out of the hospital. I noticed every time I went into the hospital I started to feel a little bit ill. In fact, I started feeling ill getting ready to go to the hospital. That was probably the biggest indication for me that it wasn’t really the right thing for me, even though I had built myself into this idea that I was going to become a doctor. I’d committed my head, I’d moved to another state, I’d resettled in a new city and I thought I was going to do that.

Pamela Wible: How old were you when you decided this?

Daniel Herzberg: I’d actually gone and done another degree in humanities and literature before, and I’d taken a couple years to reevaluate things. It was especially hard because this was the second degree I was going for. I was now twenty-seven years old, finishing up my second bachelor’s degree, and the thought of not pursuing medicine was very difficult, especially given that I’d moved away from my family. I’d moved to another state. I’d reorganized my life around pursuing this path. It was very, very difficult to pull out and say, “I don’t think this is me. I don’t think this is what I want to do.” It really triggered an existential moment of reflection for me when I was going through all that.

Pamela Wible: Wow. So most docs you interviewed were not super content with their lives. They were not real excited to go to work every day. They are boxed in by all these stacks of journals and such and they somehow feel they will always be safe as long as they’re moving high volume in their own cubicle. Is that the sense that you had?

Daniel Herzberg: I remember you used a term that stuck with me. You said you didn’t want to practice McMedicine. This assembly-line medicine. And the more I looked at that, the more I started to really notice the volume that they had to see crowded out some of their own joy, humanity, peace, being able to actually take pleasure in what they were doing, other than just one patient after another. Now when I talk to doctors, I’m conscious that I don’t want to stray the conversation too far, because I know they only have a few minutes to talk. Then they have to go chart everything.

Pamela Wible: So what are your concerns about how these young adults are considering careers in medicine? What would you recommend to them now that you’ve been on the other side, both sides of this?

Daniel Herzberg: You should make big decisions with your eyes open. You should know what you’re getting into. You should know the good and the bad. If you have a rose-colored view of things, at some point you’ll learn the bad anyway, and then you might not be in a position to make a decision to the same degree you could when you were younger. So I just really encourage teens and young adults to basically go and research everything they can, learn as much as they can about the medical field beforehand. So that would mean doing any online research, but also interviewing doctors. As I mentioned, I talked to about thirty different healthcare professionals. I would talk to as many as you can possibly find, even to ask them to go to lunch or to offer to take them out to lunch, to talk with them and interview them.

Volunteer in hospitals. Get exposure to different departments, different areas of medicine, and always keep in mind that there’s an option to not go this route. You want to find the one that’s the right fit for you. You don’t really need to decide when going through medical training what you’re going to do before you finish med school. But at the same time you should have some kind of a guiding vision of what you want to be doing. For example, I was talking with one guy who got an internship in an emergency room. He realized that he resonated with that because he liked the adrenaline. He liked the vibe, he liked the energy, he liked all the doctors, he wanted to be that kind of a person, and everything about it he resonated with. That was really good for him—a good fit for him. I talked to other people who have done stuff like that with plastic surgery or other specialties that they just really resonated with. One of the biggest things I wish that youth knew before they go down the path is they should spend as much time as they can just getting exposure to the field.

Pamela Wible: Yeah, I absolutely agree with you because I think people get stuck in something that you’ve mentioned before—this trance state—which I definitely want to hear more about. I personally think it’s really important to enter medicine with a very clear vision of where you want to go. Sadly medical students now tell me about 75% of them are on antidepressants or stimulants or both just to make it through medical school. It’s so competitive and they’re so very stressed out with the way medical education is taught these days.

I always had a clear vision of being a family doc, doing house calls in a small town. I knew exactly where I was going. I was immune to detours and taking bad advice from naysayers. But if you go into medicine with a totally open mind and you have no idea what specialty you’re going into, then you could end up in a specialty for absolutely the wrong reasons just because, hey, you’re a miserable third year, but the one guy that was nice to you was a neurologist, so you decide to go into neurology because you think they’re nice. You know what I mean? People make very weird decisions based on just the random personalities that they end up getting rotations with.

The other thing that I’m really concerned about is people choosing specialties based on what they think they will enjoy as far as technical skills, but I don’t think that they’re assessing their tolerance for business models, because there are certain specialties that will lock you into working for a hospital system the rest of your life, and you will have no autonomy to open your own outpatient practice. Just because you love anesthesiology, you have to assess, “Am I a team player? Would I make it working in a hospital setting the rest of my life,where I could never be my own boss?”

Daniel Herzberg: Not only that, but what if you pursue a path where the people don’t actually appreciate what you’re providing to them? Let me give you an example. One of the things about the role that I’ve had in working with teenagers is opening up different kinds of conversations with them, so I work with them a lot on their college essays. I had one girl who kept telling me that she was interested in going into medicine. When we were working on her college essays, I asked her about different topics, things she could write about, and she mentioned that she had gone and done some house building in the Dominican Republic. She said, “But I don’t really want to talk about that. I don’t want to write about that.” I said, “What’s going on there?” I probed a little bit further to find out what was happening there with that particular story.

It turns out that she didn’t have a good time there because she felt that when she was there trying to help them and she just kept basically being sexually harassed. She had guys catcalling her and kept telling her this certain work wasn’t for girls. They would take her tools from her and take the bucket that she was carrying away from her as she was trying to do her work. When she was reflecting on what that experience meant to her, it made her really uncomfortable. Part of what I think she realized was that she was there providing a service to folks that they didn’t appreciate. They didn’t even seem to respect who she was as a person as she was coming there to help them. She realized when she started thinking about what that meant for her career, very indirectly, she realized she didn’t want to do a professional path if people didn’t appreciate her, people didn’t respect her. So she still wanted to give back, but she decided to go into medical research rather than direct patient care. For her, that provided her the opportunity … She’s still giving back and helping people, but not with so much on the line personality-wise of being so exposed to not really being accepted and appreciated.

I think that’s a thing for a lot of doctors, is that they go into it with this big heart, that they want to help people, but people on the other end may be thinking, “Oh, you’re just a wealthy doctor helping me. You’re so well off and you’re doing so great,” and maybe even being a bit disparaging sometimes to the people that are trying to help them.

Pamela Wible: Then they can leave these nasty online reviews and turn you in to the medical board. Just unreal.

Daniel Herzberg: That was one of the things that got me also, was when I looked at the liabilities associated with medicine that were really quite intense. You do all this work, you invest hundreds of thousands of dollars and all kinds of opportunity costs in going through this education, with premed and then med school and then your residency, and all it really takes is one significant mistake to just tank your career. The stakes of that just really threw me off. I was like, “That’s a lot of stress.” I didn’t want to live with that level of stress.

Pamela Wible: It doesn’t even have to be a mistake. It could just be one bad egg passes through as a patient that has a grudge with you and turns you in for something that then you have to go through an investigation. You didn’t do anything wrong. I’m going to pull up a story that I have got to share with you. It’s very intense.

Daniel Herzberg: While you look that up, what I was going to say is that at some point people get caught up in a certain kind of a trance that guides them from one thing, leads to the next thing, leads to the next thing. I was talking one time with a guy who described himself to me as a college dropout. I said, “Tell me about what happened.” He goes, “I got through two and a half years of college, and then I got sidetracked with an opportunity and I dropped out of college to go do that and never went back to school.” I said, “There’s a lot of other really good college dropouts. There’s very successful college dropouts. People who don’t even finish their freshman year, like Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs. There’s a lot of people who have been extremely successful who are so-called college dropouts who employ a lot of people who completed college.

Pamela Wible: There’s a lot of very brilliant entrepreneurs out there who got off the traditional educational trajectory rather early.

Daniel Herzberg: I was just watching a video recently where the speaker was talking about how C students employ A students. Sometimes the B students manage the A students and the C students employ the A students. That’s not always the case, but it’s not necessarily a correlation to say that those that go to college and get their degrees and check off all the boxes and do everything right are going to be at the top either. But in terms of the trance, I just think that people get caught up in this educational trance, whether it’s because they get attached to what it feels like to be in a certain educational environment, like in a certain university or be pursuing a certain degree, or if there are certain classes they have to take in sequence they get committed to that process and they fall into an identity trance in that process. And they don’t realize it can stay with them even long after they’ve either completed or stepped off of that. It’s still kind of insufficient that they haven’t done enough.

I just believe in free will. You can choose what you want to do. Part of that involves recognizing maybe you’ve been in a bit of a trance and waking up from that and then realizing you have choice in how you want to live, and it doesn’t necessarily have to be dictated by the things you’ve done years before or the day before. You can choose to do what you want to do.

Pamela Wible: Yeah. That can actually be very liberating to decide to give up the dream that you’ve had since you were seven years old and revise it with the mind of a fifteen-year-old or twenty-year-old that you now are.

Daniel Herzberg: Right.

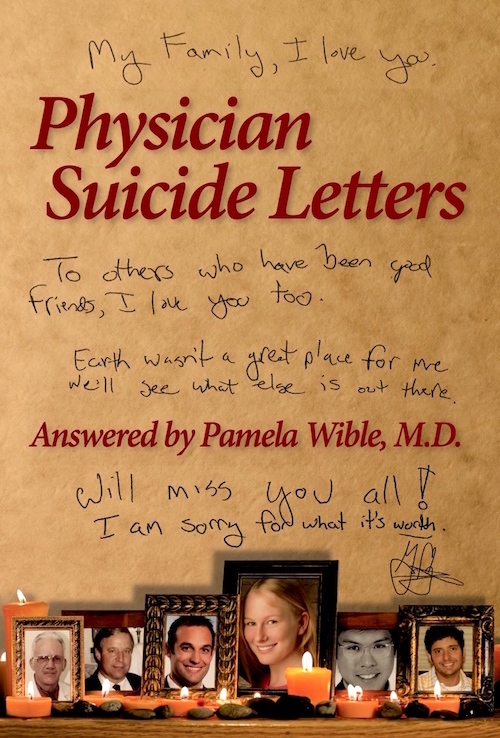

Pamela Wible: I just want to give people permission to live their dream in medicine—and live your dream outside of medicine. I’m not attached. What I can’t stand is watching people be victims—falling into that victim mindset, feeling trapped, hopeless. I do a lot of work preventing physician suicide and this hopelessness,starts brewing pretty early for some.

Daniel Herzberg: It does. The thing is also that a lot of times people will hide that. The people that I interviewed, I asked some questions that often made them uncomfortable because I would ask them things about, “Would you do it again?” And they’d pause and I didn’t get a lot of affirmation that they would necessarily want to do it again. The other thing I noticed was that the people that I would interview would go down to the cafeteria and I looked at the food that they would eat and realized they’re eating all this crap. Mac and cheese and all sorts of stuff they were spooning out to the physicians and they would eat this. I started to think about what are these folks … What’s their education look like? They must have learned about nutrition and health in their medical training.

As I looked into that, I realized that most physicians had no training in nutrition, had no training in areas that were related to wellness and health and vitality and things like that. I only found one school … It was actually the top-ranked school for family medicine. I believe it was Oregon Health Science University. They only had one course on nutrition. When I looked around, I found that in general it was unusual for med schools to even have one three-hour lecture on nutrition, and that the idea of having an entire course on nutrition was something that was innovative and breakthrough and was supposed to be somewhat emulated, but to me it seemed very limited. They only had one three-hour course, typically, in nutrition.

Pamela Wible: Yeah, here’s what I learned in nutrition during medical school. First of all, we definitely had a lecture on parenteral nutrition, which is what to do when you can no longer use your mouth to eat and you have to be fed through your veins. We did have that. And then I got made fun of because I was vegetarian. I had a surgeon that was lecturing us who basically spent portion of his lecture making fun of people for going to health food stores and buying from the bulk bins. I had that lecture. I wanted to get extra training in nutrition, so I signed up for a fourth-year elective—which was pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. They sent me into a room, I don’t know if I told you this before, where I was assigned to this guy who looked just like Homer Simpson, and I had to sit with him for a month, and we were surrounded by little rat bones in jars, and he had me do ridiculous research in the library looking ridiculous stuff up. It was not helping me be a healthy person or be able to help my patients make the right choices with food.

Daniel Herzberg: Right, but you kind of entered your training to get through and get your degree, but it didn’t really elevate you to learn what you wanted to learn.

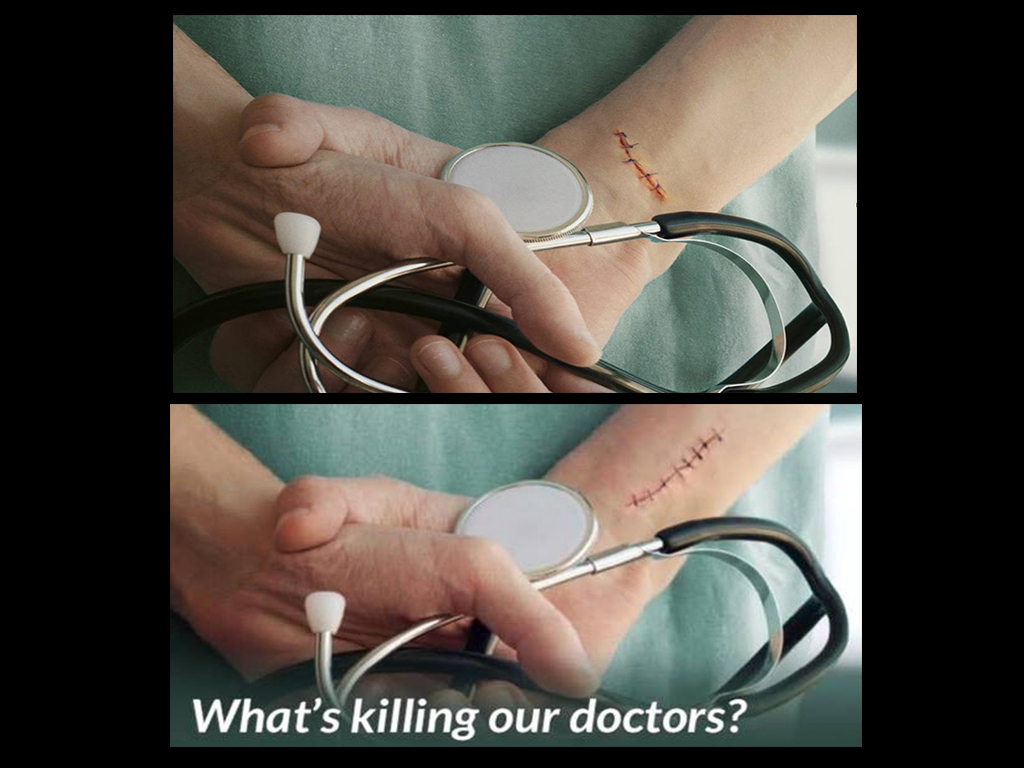

Pamela Wible: Absolutely not. So I definitely want to share this message I just got. Speaking of one thing that could upend your entire career. This is a note that I got the other day. I just had this article that came out in the Washington Post on physician suicide, and as a result I got a flurry of emails. This one came in that says, “I caught your article about physician suicide while on my computer. I’m an RN. My husband, John, was an ER physician in Santa Maria, California in 1995. A man was found under a tractor that had rolled onto him. It was over 90 degrees. Two people biking by happened to hear him calling out. Twenty-four hours later, he’s hydrated in the ER, X-rays are done, he’s all tucked in. Attending called, he was admitted. The man had no insurance. He was an uncle to a hospital employee. My husband actually undercharged for his services because he felt bad for him. The local news got the ‘miracle story.’ People sent the man money. Months later, the man sued everybody that touched him. For two years, my husband corkscrewed into major depression. In his head, he went from a bad doctor to a bad husband to a bad father and a bad person. Nothing I did helped. He shot himself, leaving me and four children under the age of ten years old. The legal case was thrown out for being ridiculous. I thought I was the only one.”

Daniel Herzberg: Wow.

Pamela Wible: That’s a huge price to pay for trying to help.

Daniel Herzberg: Yeah. This is the risk of the helper in our society, is that you help somebody and they may not appreciate it. Or they may even turn it against you, if you get somebody who’s really tweaked out.

Pamela Wible: Very sad.

Daniel Herzberg: That’s just a sad, sad story. But also, think of how many doctors live with the exposure of somebody who could turn things against them like that.

Pamela Wible: Especially in an emergency department where people are passing through and they have no real commitment to a long-term relationship with you. With an entitled population of people who are litiginous it could go south pretty quickly, right?

Daniel Herzberg: Yeah, especially dealing with populations of people who have substance abuse issues, who have all kinds of strange motivations, who are willing to throw anybody else under the bus to get what they need.

Pamela Wible: Right. So do you feel there are things that these young premed and medical students should learn that are not taught in school?

Daniel Herzberg: There’s a lot. First of all, they should learn about entrepreneurship. To me, that would seem like an important part, because otherwise people will just keep, more or less, directing and telling you what to do in your path. It’s important to realize that there’s other options outside of that. Apart from that, I also think that it’s important that youth and young adults learn about some things that are more personal development—related than what they’re going to learn in school.

If you think about it, you never really learn in high school or college or grad school, unless you pursue a particular course in this way, about how to have a successful relationship, how to set proper boundaries in a relationship both in terms of romantic relationships but friendships or clients or patients. The fact that they haven’t actually learned how to have effective relationships … I find that a lot of the doctors that I’ve talked to, especially soon after they graduate, in some ways are a little bit behind. They’re a little bit arrested, because they’ve been so preoccupied with those studies, they haven’t gone through the normal stuff that most people will go through, romantically, at least, having relationships, because they’ve just been too preoccupied. That yields all kinds of strange dynamics later on when they’re older, because now they haven’t learned things when they should have learned them. Other folks would learn them at the normal course, about dating and having normal healthy, successful relationships.

Pamela Wible: The number of women in their mid-thirties who I talk to in medicine who are having panic attacks and various mental health disorders as a result of the occupation. One of them, a neonatologist, and an ER doctor comes to mind. They are so distressed because of having to tell people their children and their babies have died all day long. It’s not a cakewalk. They have PTSD just from what they’re witnessing at work. They really haven’t had any time to date. Their eggs are frozen, hoping that one day they’ll meet somebody to be able to get married and have a family with. With the extent of their mental health issues and the eighty-to-hundred-hour work weeks, imagine, when would they be able to date, and what would that date actually be like? Could they go to a movie and go out to dinner and have normal conversation? You know what I mean? They’re so distressed?

Daniel Herzberg: Especially for female physicians, I think it’s especially hard, because there’s still, I think, an inherent dynamic in our culture where the man oftentimes wants to be the one who’s at least equal or maybe a little bit more earning, or in a slightly more powerful role, whereas the woman might be home more taking care of the kids or a little bit more towards that role. For strong career women who want to have an equal relationship, they can sometimes come across a little bit dominant to guys and maybe it can freak them out a little bit.

Pamela Wible: I can vouch for that. I’ve freaked out my share of men. I have.

Daniel Herzberg: What that partly means is that the pool of men that you can date …

Pamela Wible: Is shrinking rapidly.

Daniel Herzberg: It diminishes rapidly, because there’s not many guys who can handle that, a really strong woman who has that same level of parity.

Pamela Wible: Good point. Yeah, I really like to ask people when they contact me, premed and young medical students, and they’re wondering and they’re confused about their future, I’m like, “Hey, paint a picture for me of your life ten years from now. I just want to know. How many kids? Where do you want to live? How many hours a week do you want to work? And then let’s reverse-engineer the steps to get there.” Because neurosurgery or being an orthopedic surgeon or whatever might not lead to the destiny that you’re really hoping for. You know?

Daniel Herzberg: Yeah. I think you’re getting at something that I think most youth and young adults actually lack the capacity to think that far out. Most adults, I’ll say thirty and up, are pretty good at planning out for the next ten, twenty, thirty years. They have some vision of what that’s going to look like. Maybe they’ll think about retirement, things like that. Most teenagers, they’re fantastic at being in the moment. They’re awesome at entertaining themselves and enjoying the moment and doing things in the moment, but they don’t really have the long-term cognitive skills to really be thinking about how to plan out the future. They might plan out maybe finishing college, or they might plan out someday maybe imagining being a doctor. But they oftentimes have trouble really imagining what it would be like beyond that point.

At the same time, they’re taking on all this debt and they’re taking on all this commitment and putting in all this time towards this path. That’s one of the reasons why I’ll often go the extra yard to make sure that they’ve really thought about and investigated and learned about what the path is they want to go towards, even if they know they want to continue on a path where they want to explore. Just to make sure that they really go in with their eyes open, because the degree to which they don’t really realize what they’re getting into often yields a pretty much corresponding level of disappointment and frustration down the road, because they don’t really understand what they committed to.

Pamela Wible: So I think in wrapping up can you to share what would be appropriate or when somebody could maybe contact you. I know you have some services that you offer. I’m just wondering, first of all, what option does a premed or med student actually have, especially if they want to get off the exit ramp there. Then also, physicians are pretty miserable these days. I help a fair number of them open their own clinics, but some of them might want to just get out of medicine, and could you speak to that and what you recommend?

Daniel Herzberg: Let’s talk about the premed and the med students. They’re both going to have different options, but for premeds there’s just huge demand for folks with background and training in science technology, engineering, and math, the STEM fields. Premed students actually have a whole array of options open to them if they want to go into a different area in science, if they want to take that, if they want to go into teaching, if they wanted to go into business. There’s just many, many options open to them. They’re just getting the basics of their core education down. Once they finish their premed coursework, they pretty much have the world open to them. In fact, premed is not a bad training for developing your mind and developing your knowledge base to open up a lot of different options. If someone is in med school or if they finish med school, they’re still going to have options that don’t necessarily involve going and working as a clinician. They could go into research, they could go into engineering. If they wanted to, they could get involved with lots of different opportunities in entrepreneurship and startups and things like that. I think there’s lots of choices they have along the way if they wanted to get off track.

There’s also always just the possibility that they can pursue some other thing that they’re really much more interested in, that even doesn’t necessarily align with what they were studying in school. I did that, and I’ve had a pretty happy career. I’ve enjoyed a lot of freedom. One of the things I decided when I was in my pre-med coursework was, I just wanted to be able to get up when I wanted to wake up, which a lot of doctors don’t have the luxury of doing. As I realized talking to doctors, they often seem sleep deprived. For me, I thought about that and structured my career being able to dictate my own hours. Sometimes it just involves being open to exploring, and I would say that the earlier you open yourself up to really traveling, exploring, looking into other fields, looking into other things, the more quickly you’ll be on the path that’s more aligned with who you actually are, rather than just keep doing what you did the day before.

As far as for actual physicians, doctors who are already actually in the field, I do have some solutions. This kind of ties over to the business consulting work I’ve been doing also, where I’ll actually work with doctors to actually structure out ways to financially exit from what they’re doing, whether they own a practice or if they’re working as physicians, but ways to actually set up. More typically for folks who are the owners of a practice, or if they’re one of the co-owners in the practice, to help them actually exit that, and if they want to move on to something else, they can.

Pamela Wible: That’s awesome. How would people reach you if they’re interested? And I don’t know if you’re still helping premed and med students.

Daniel Herzberg: I’m still open to talking to people about that stuff. I feel like it’s an important consideration to make, and again, it’s one of the reasons why I did so much work with teens and youth, is because it’s one of the most highly leveraged moments in a person’s life, when they’re making decisions about what they’re going to do next, and decisions that will affect the next five, ten, twenty, forty years of their lives. I do not mind having those conversations with people. I think it’s one of the most important, sacred roles I could have, is actually helping somebody figure out how they’re going to navigate the next stage of their life and what path they’re going to go down. If people are interested in talking further, they can go ahead and email me at dcherzberg@gmail.com

Pamela Wible: Awesome. Daniel, this has been incredible, and I’m really, really happy that we got to do this and share our private conversation with the world, because we’ve had amazing conversations over the years, and you’re a gem as far as information for these young people going into medicine. You’ve sort of done the research for them, in a way, and between the two of us guiding them, certainly they could make some better choices with their careers, so thank you.

Daniel Herzberg: I appreciate that, Pamela. I also just want to acknowledge you again. I want to thank you, because if I had not met you at that time in my life … I know that you were very instrumental. You really helped me to make that change. Seeing what you were going through at that time and how much stress you were dealing with, trying to fit into a conventional medical framework, you really affected the course of my life, so I appreciate you for helping me to do that. Thank you.

Pamela Wible: Yeah, no problem. I’m happy to help anyone who reaches out. I would just encourage anyone listening to this or reading this blog later to please ask for help, because that’s one of the skill sets that helpers also have not honed. We tend to want to give other people help but not ask for help. I think I would just encourage you throughout your career to ask for help, because help is out there. You do not have to struggle alone. You do not have to be isolated and withdrawn. We want to help you make the right choices.

Daniel Herzberg: The irony is that a lot of doctors, they’re the helpers, but there’s no one to help them. They have to ask, because there isn’t really a framework to get that always necessarily. So if they don’t ask, they won’t get the help.

Pamela Wible: You have to be assertive about it. Daniel and I are offering ourselves to others so please take us up on that offer. Thanks for being here and I will go ahead and say goodbye, and we will get this out to everyone. Thanks for joining me, Daniel.

Daniel Herzberg: You’re welcome, Pam. Thanks so much.

Need more inspiration along your medical journey? Contact Dr. Wible.