(Listen in above to a rerecorded keynote—due to a fire alarm during event—or read transcript of Dr. Wible’s presentation below)

Michael Phillips MD: Good morning everybody. I want to introduce the lectureship and remind everybody who Gil was. Gil was originally from Philadelphia and then moved to Oregon where he joined The Gastroenterology Clinic, which at the time was the only GI-specialty clinic in Oregon. He became one of the preeminent gastroenterologists well-loved by patients and staff alike and known for his outstanding humor, his clinical skills, and patients who absolutely adored him. I continue to take care of patients that he took care of 20 to 25 years ago and they still think of him as their gastroenterologist. I’m just kind of standing in. That’s the kind of guy Gil was. Gil really dedicated himself to education. He was Outstanding Teacher of the Year twice—a testimony to who he was. He died unexpectedly at the age of 50 [on a ski trip, not a suicide]. In response to his untimely passing, we established this lectureship 20 years ago. We’re here today to commemorate him and to continue to use his legacy to help facilitate our practice and humanity in taking care of patients.

It’s really with a great pleasure that I get to introduce our speaker today, Dr. Pamela Wible. Pamela is family physician born into a family of physicians. Her parents actually warned her not to become a physician. Shortly into her first year of medical school, she experienced the adverse effects of medical education on her own mental health. It wasn’t until 2012 after losing three colleague physicians to suicide that she began to investigate the mental health crisis among medical students and fellow physicians.

For the past six years, Dr. Wible has reported on doctor suicides and human rights violations in medicine. Her articles have been picked up by major media including The Washington Post and Time Magazine. She’s the author of the bestselling book, Physician Suicide Letters—Answered (free copies available today). Dr. Wible has two TED Talks on doctor suicide. She’s been interviewed on primetime investigative television and featured in a new award-winning film Do No Harm that’s currently being screening at hospitals and medical conferences internationally.

In between treating patients as a solo family physician in Eugene, Oregon, Dr. Pamela Wible continues to run a free doctor suicide hotline that’s been in operation since 2012. Today, she’ll share the results of her investigation into more than 1100 physician suicides and reveal simple truths and solutions to prevent the loss of our healers. Please welcome Dr. Pamela Wible. Thank you.

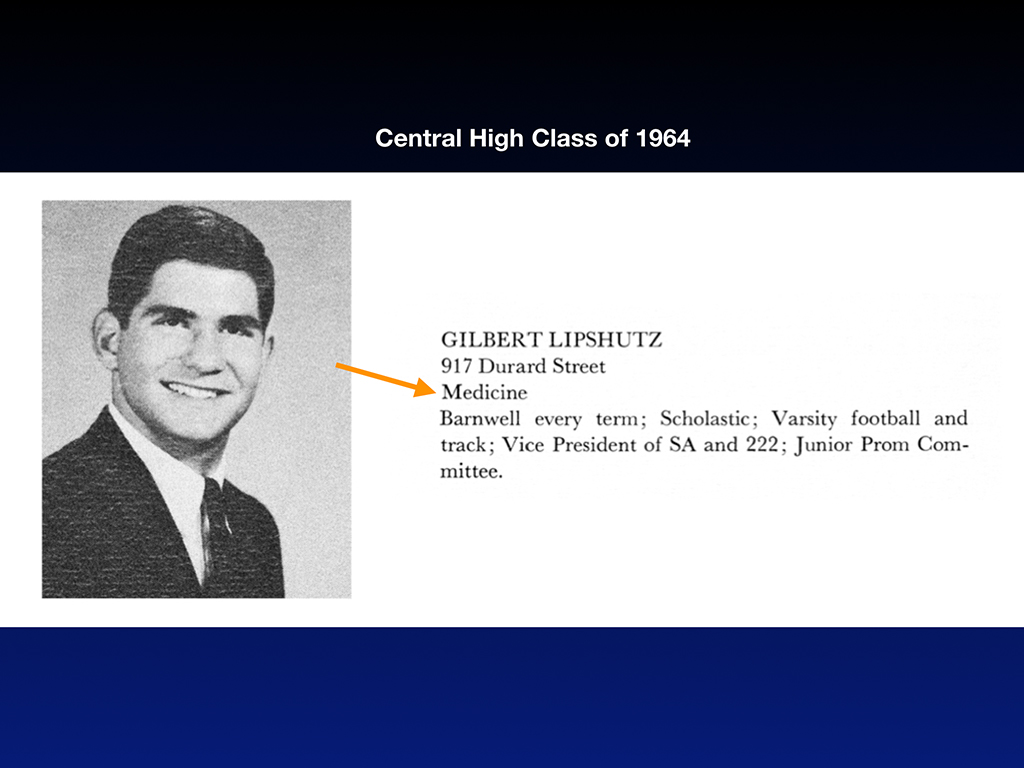

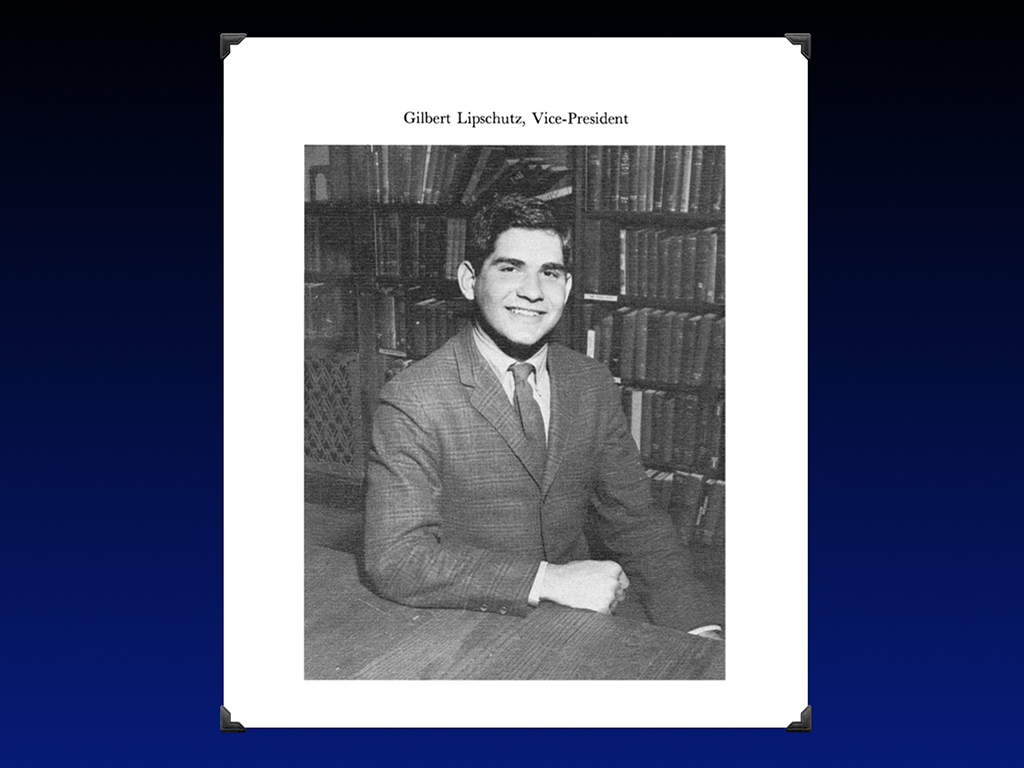

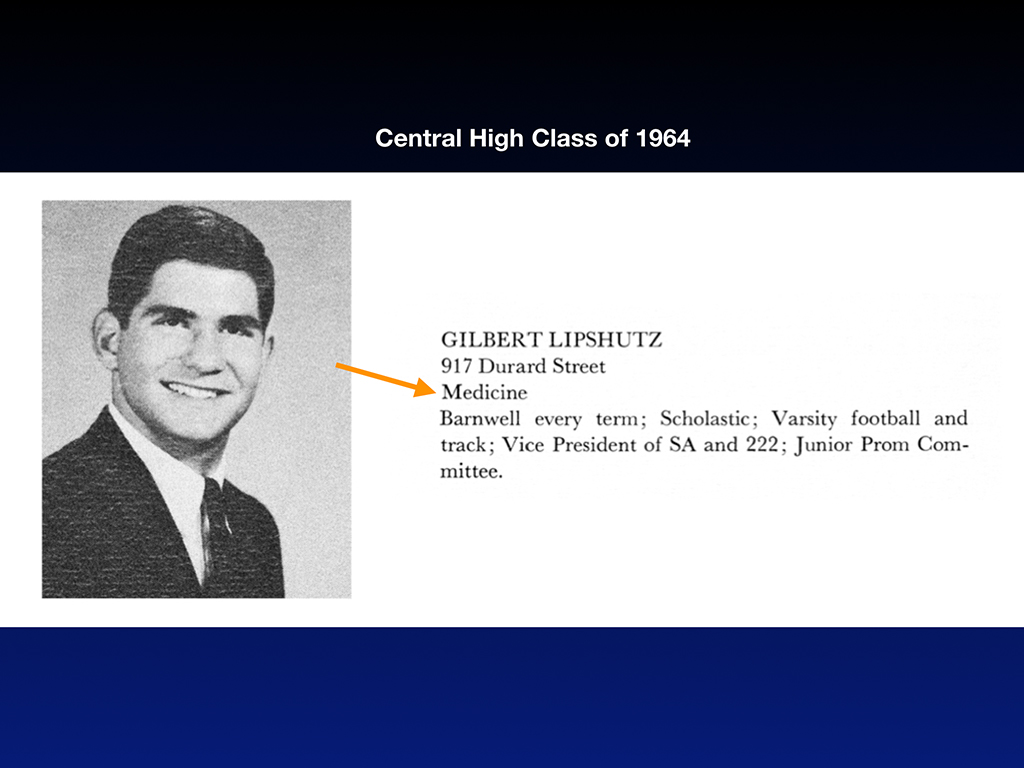

Pamela Wible, MD: Thank you all so much for being here. I want to thank Providence for hosting this event and taking on this topic of doctor suicide. Though I never met Gil in Oregon, our paths did sort of cross in Philadelphia. Turns out my dad and Gil attended the same high school where Gil was actually the vice president of his graduating class.

There he is. Teacher of the Year at Providence as a young guy before he had the mustache. Gil knew from early on that he was headed for a career in medicine. He declared that right away at Central High.

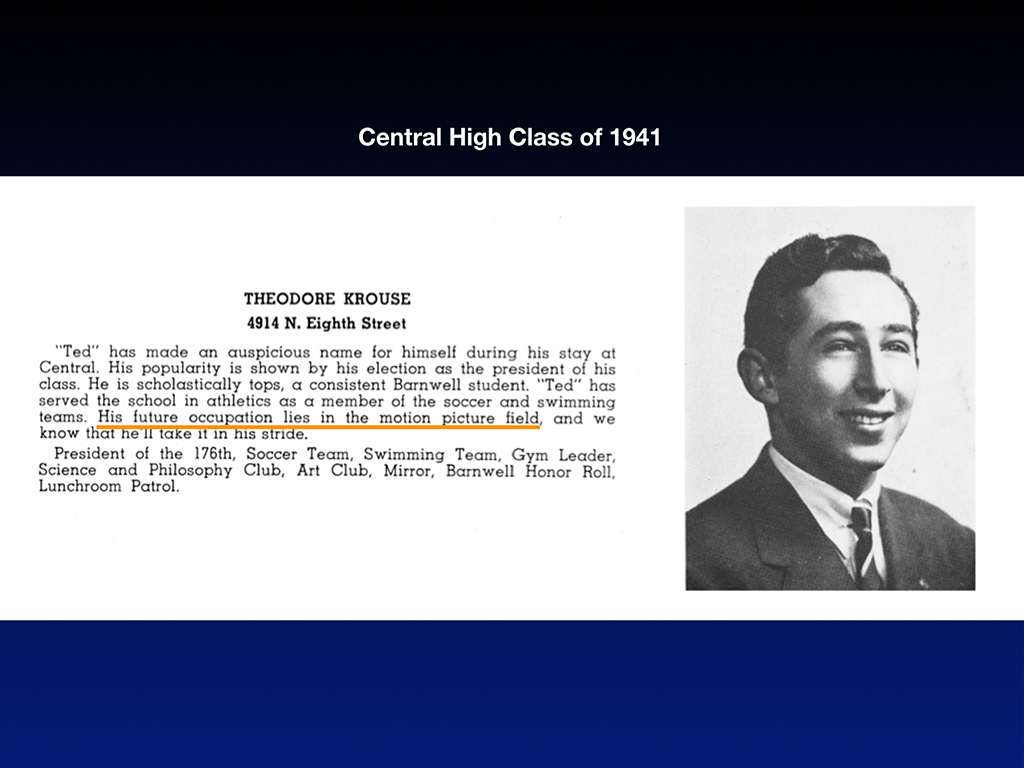

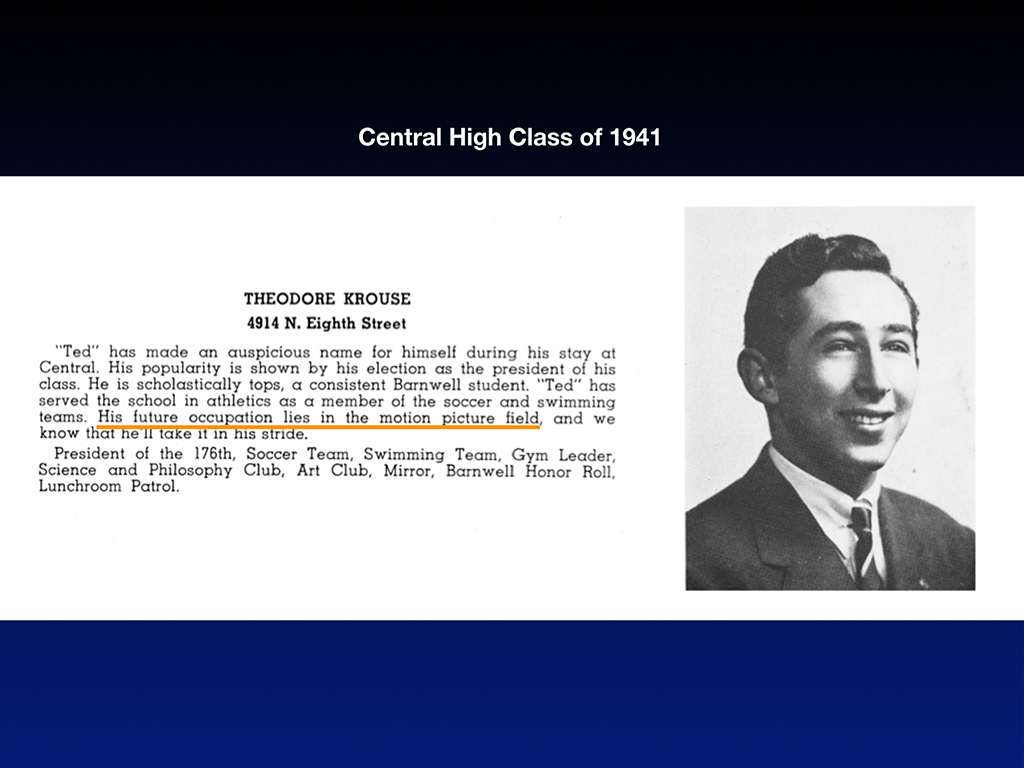

Unlike Gil, my father assured his classmates as the president of his class that his future occupation would be in the motion pictures.

Like a good Jewish boy he relented to parental pressure and became a doctor. Both Gil and my dad did some of their training at Hahnemann in Philadelphia. Both pursued internal medicine. How odd is it that I’m invited to do this lectureship and my father and Gil have such parallel paths in medicine.

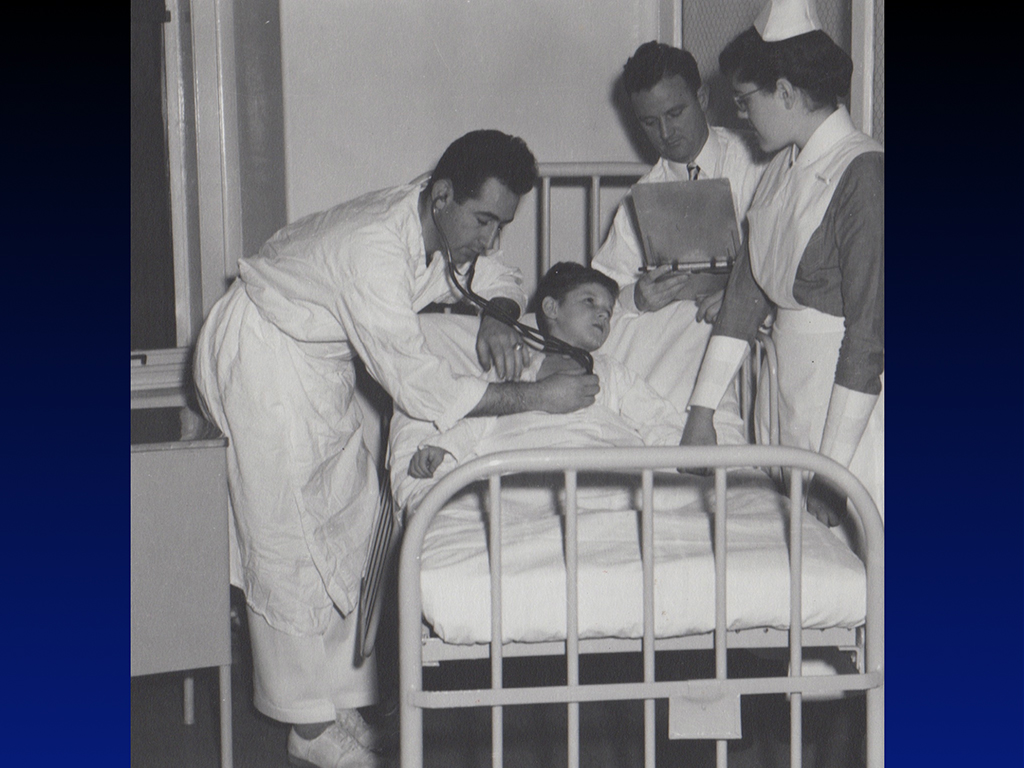

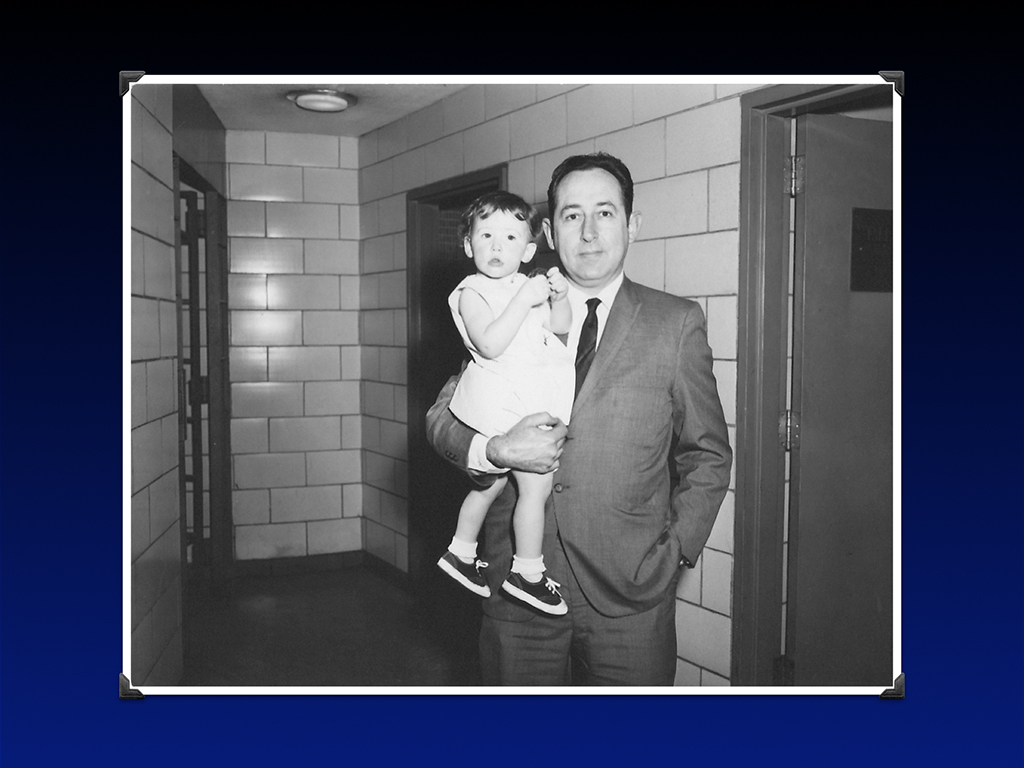

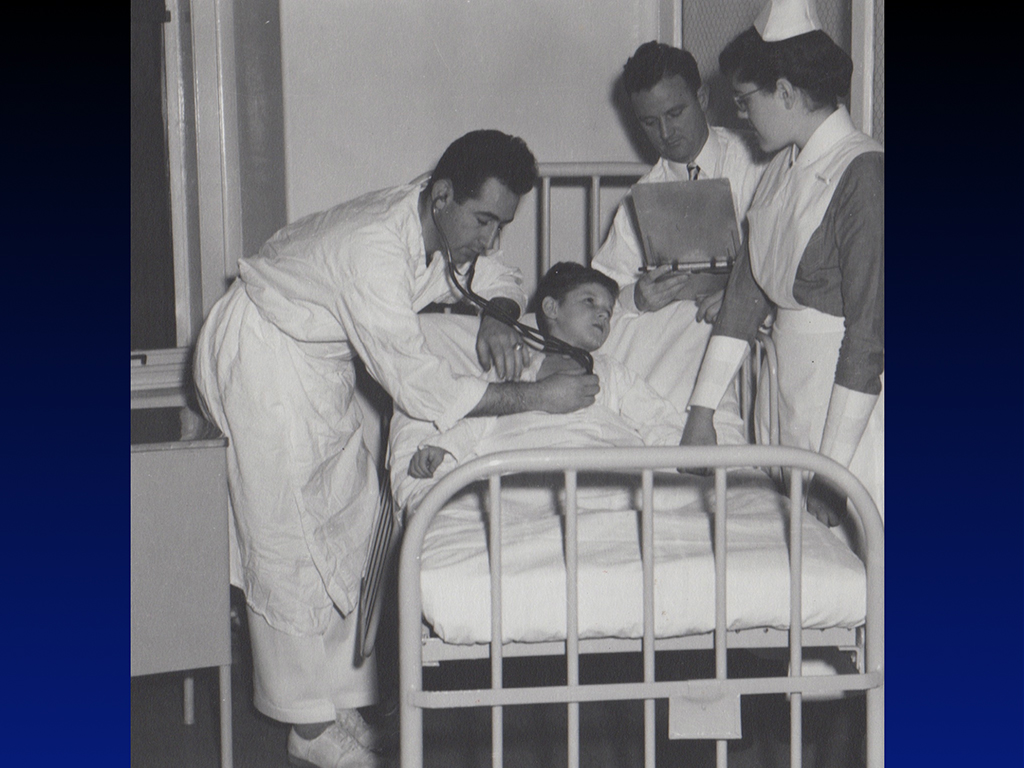

Unlike Gil who died at the height of his career, my father practiced medicine for 62 years and retired at 87. He died four years ago this morning at 91. My dad ignited my interest in medicine. Here I am following him around in the hospital. With physician parents I grew up in the hospital hallways back when they didn’t care if your kids crawled through the morgue with you. I don’t see many physicians’ toddlers wandering the hospital hallways today. Too bad. I had so much fun playing with the paraffin in the pathology department and looking at this huge glass jar with all the bullets and foreign bodies he found in patients (that I thankfully inherited after he died).

Dad’s a pathologist. I think the human drama of running a small neighborhood internal medicine practice was a little bit too much for him, so he chose a more predictable patient population in the morgue. My mom is a psychiatrist so I tagged along as a child at the state hospital. So I spent my time with mom hanging out with the seriously mentally ill and with my dad I got to hang out with dead people. Neither of my parents needed stethoscopes so I inherited all their equipment from med school too. I developed this love for medicine and a fearlessness about mental illness and death because of the unusual experiences I had with my parents—amazing for a blossoming young doctor, but for my siblings morgue visits were horrifying and traumatic.

Unlike my father, I’m much more of a rebel. Since I was warned not to pursue medicine, here I am graduating from medical school and becoming a solo family physician (who still doing house calls and practices medicine the old-fashioned way—which is kind of a rebellious thing to do in 2018!).

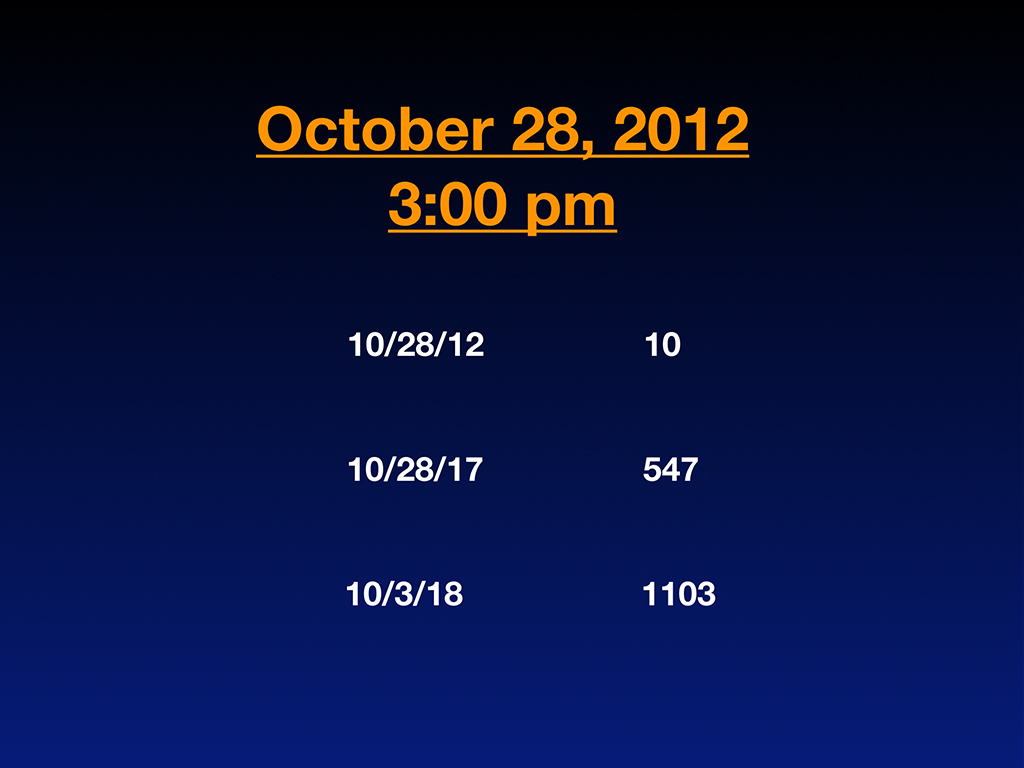

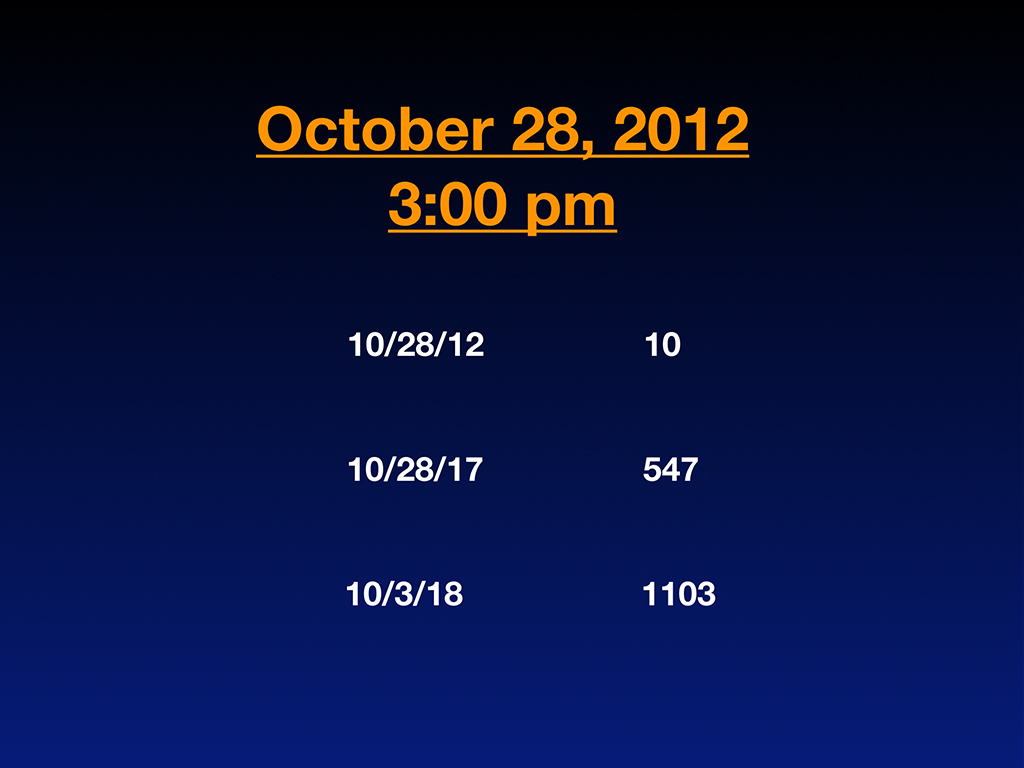

I was living the happily-ever-after life of an old-fashioned family doc in the sweet town of Eugene, Oregon until October 28th, 2012 at 3:00 p.m. when my entire life got turned upside-down. I found myself sitting in the second row of a memorial service for our third physician suicide in our small, idyllic little town full of farmer’s markets, organic food, and friendly hippies. Sitting at this memorial service, I started to count on my fingers the number of doctors that I had personally lost to suicide in my life and/or who died under suspicious circumstances that I thought maybe were suicides covered up with the classic euphemisms.

Within a few minutes, I had counted 10. Startling for me in my early 40s—the prime of my career. So I did what I needed to do to get a handle on this epidemic—I gave up knitting and mosaic mural artwork and began tracking doctor suicides as a hobby. I became completely obsessed with why so many doctors were dying by suicide. Two of the doctors on that list of 10 were men that I dated in medical school who died by suicide (not while I was dating them I want to make that clear) but later on when they were married. They died at 39 and 44 leaving wives and young children behind.

Because I am so vocal and such a prolific writer on doctor suicides, I ended up well-known among my peers for my investigation into doctor suicide and soon people began telling me about more and more doctor suicides. Five years later, I ended up with 547 cases submitted to me by physician colleagues and family members. I never went looking for these suicides. They were submitted from people calling me saying, “Hey, I want you to know my neighbor shot himself in the head a year ago. I was in my backyard. I heard the shot, I saw the police come. The family’s not really talking about it, but here’s the backstory and I want you to know what really happened to this cardiologist.”

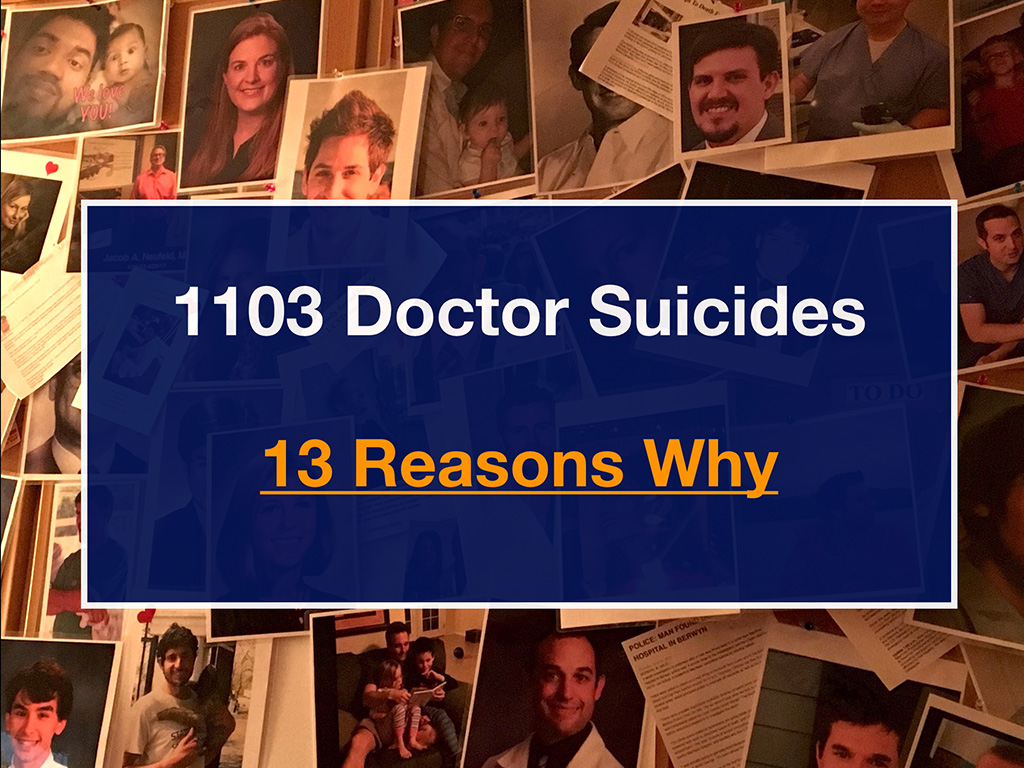

So I end up with this list—an informal suicide registry where I’m tracking by name, specialty, date, method, and location of suicide, plus any extenuating circumstances. Now I have a very deep understanding of why my peers chose to die. And cases keep coming to me almost daily. Now I have 1103 doctor suicides that I’ve personally investigated by talking to family members, friends, the last boyfriend, and medical school classmates.

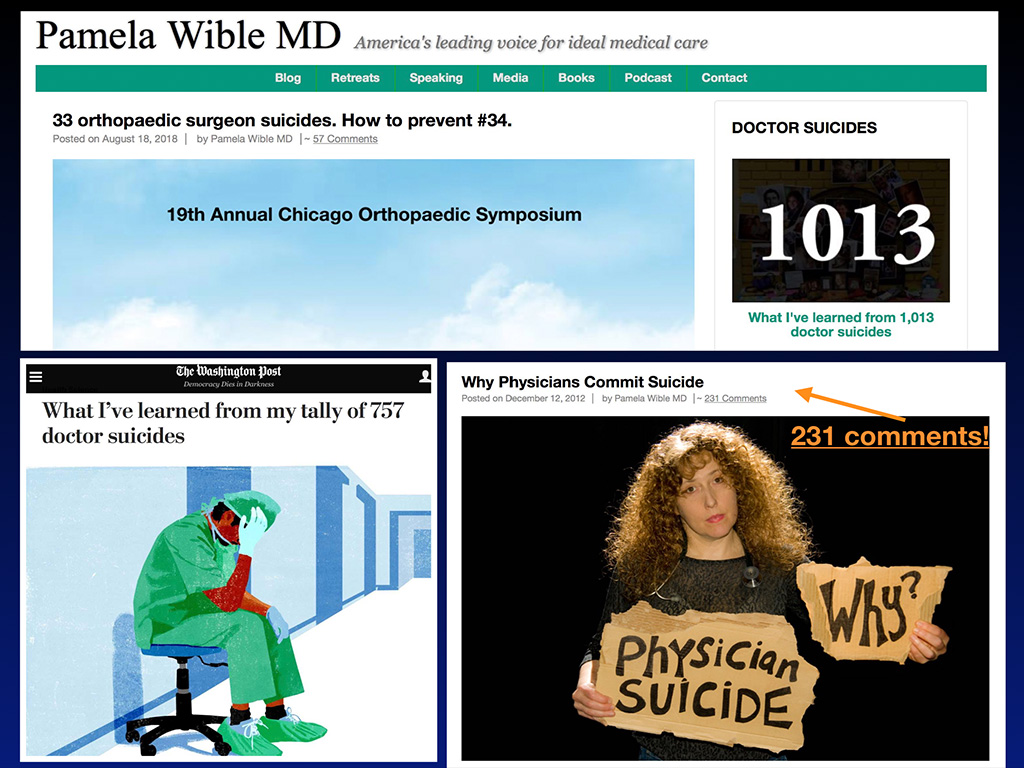

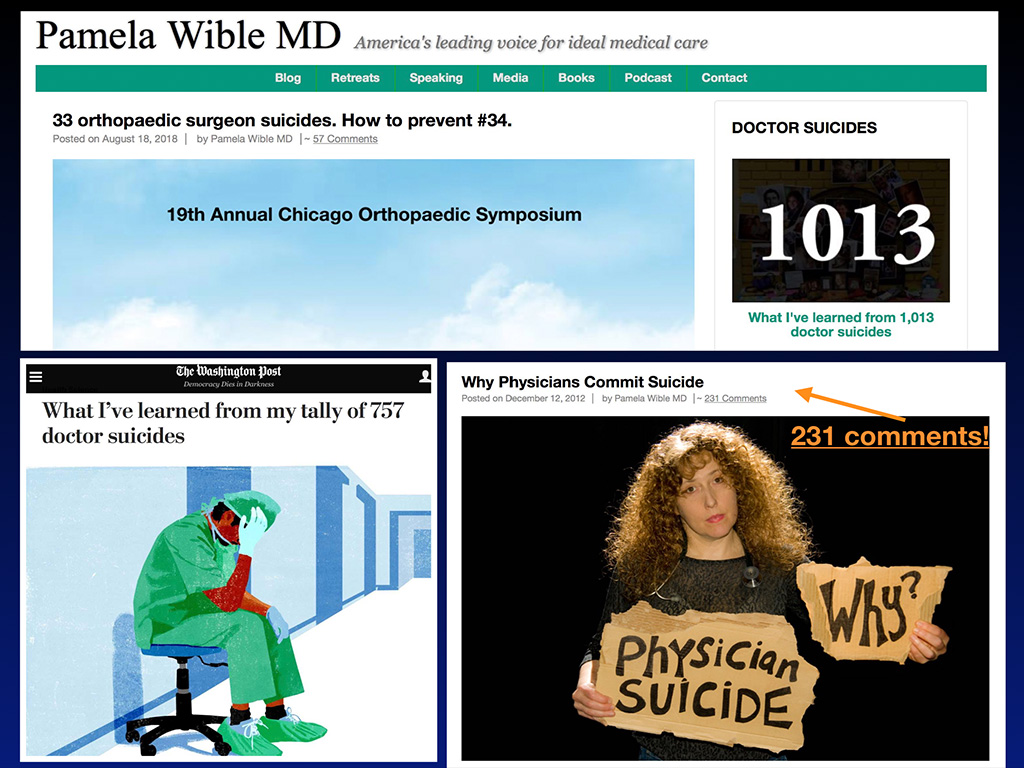

With so much content, I’m discovering themes. Here is my blog where I began to share results of my investigations. Full disclosure: Personally I’m so obsessed with this topic because I was a suicidal physician myself in 2004. I thought I was the only one. I had no indication that other doctors were suffering. I felt like the oddball, the sensitive one. Maybe I was too idealistic. I just had no idea physician suicide was such an epidemic.

Professionally, I feel called to be a healer. As a scientist and physician, it is my obligation to research why my peers are dying. So I started blogging about suicide and my blog (that nobody really read up until then) suddenly on December 12, 2012 when I published Why Physicians Commit Suicide ended up with 80 comments right away and now 231 comments. So the public response kind of egged me on to continue talking and writing about it.

Then my blogs started to get picked up by The Washington Post, like this one, What I’ve learned from my tally of 757 doctor suicides. That was how many cases I had on my registry as of January 13th this year. Here’s a screenshot of the top of my blog a month ago back when I had just over 1000 cases and reported on my latest data at my keynote at this orthopedic surgery conference. I was the only female physician speaker during this four-day orthopedic surgery symposium. I consider that a huge accomplishment. All the orthopedists only got 10 minutes to deliver their content and they gave me an hour on doctor suicide! There’s an indication that we’re making progress as a profession addressing doctor suicide.

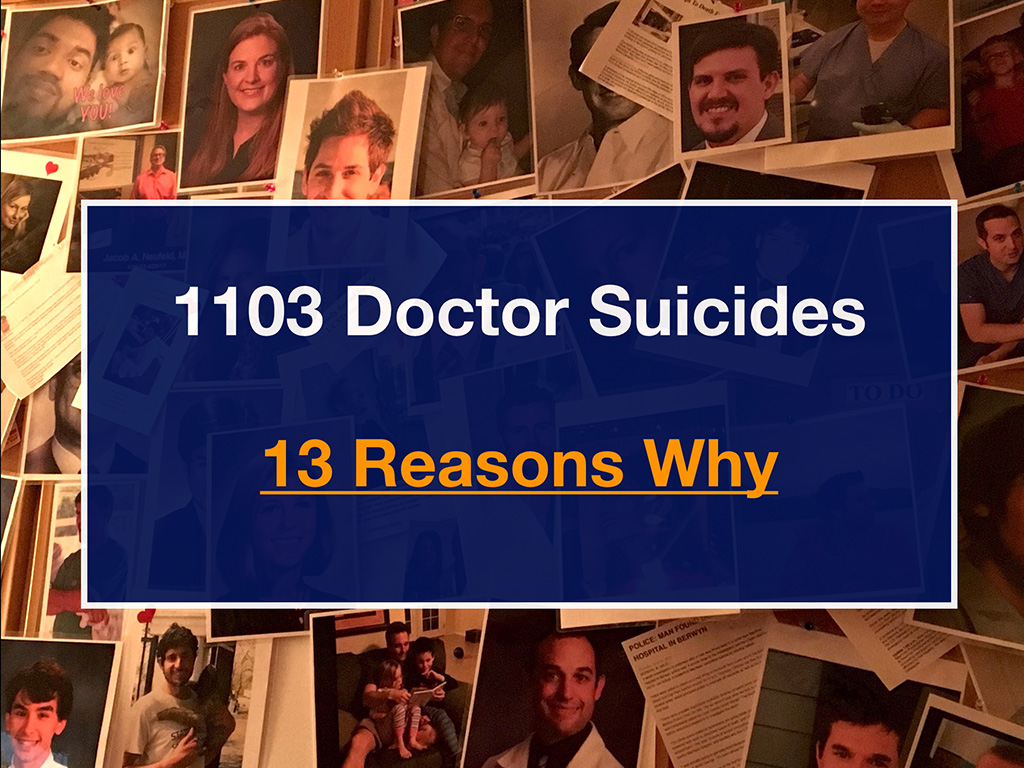

So here’s a wall in my house covered with physicians and medical students who have died by suicide. Again, I’m taking this very personally and I’m in touch with many of their family members.

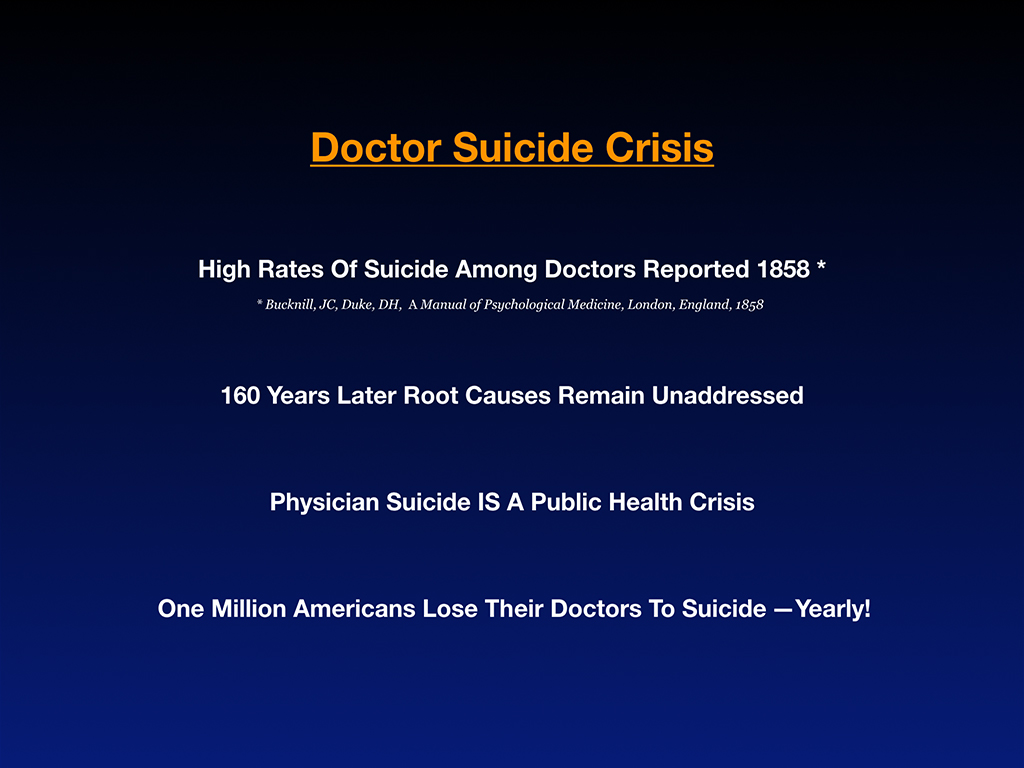

Now a bit about the scope of the doctor suicide crisis. We’ve known about the high rates of doctor suicide since 1858 when first reported in the UK. Now, 160 years later, the root causes of these suicides remain unaddressed. That’s because we don’t really understand the root causes of a taboo topic—hidden for more than a century. Because as a culture we’re scared to say suicide out loud in and we’re definitely scared to say doctor suicide out loud.

Doctor suicide is a triple taboo. Death is not a topic anyone wants to discuss over dinner. Suicide is death suddenly in your face. Now doctor suicide—the people that are supposed to be helping us are dying by suicide too. This strikes terror in the hearts of patients and makes doctors feel vulnerable. It’s just a scary topic for most people so I’m taking this on because lives on the line that can be saved today by the way we behave with each other and our willingness to tell the truth about physician suicide.

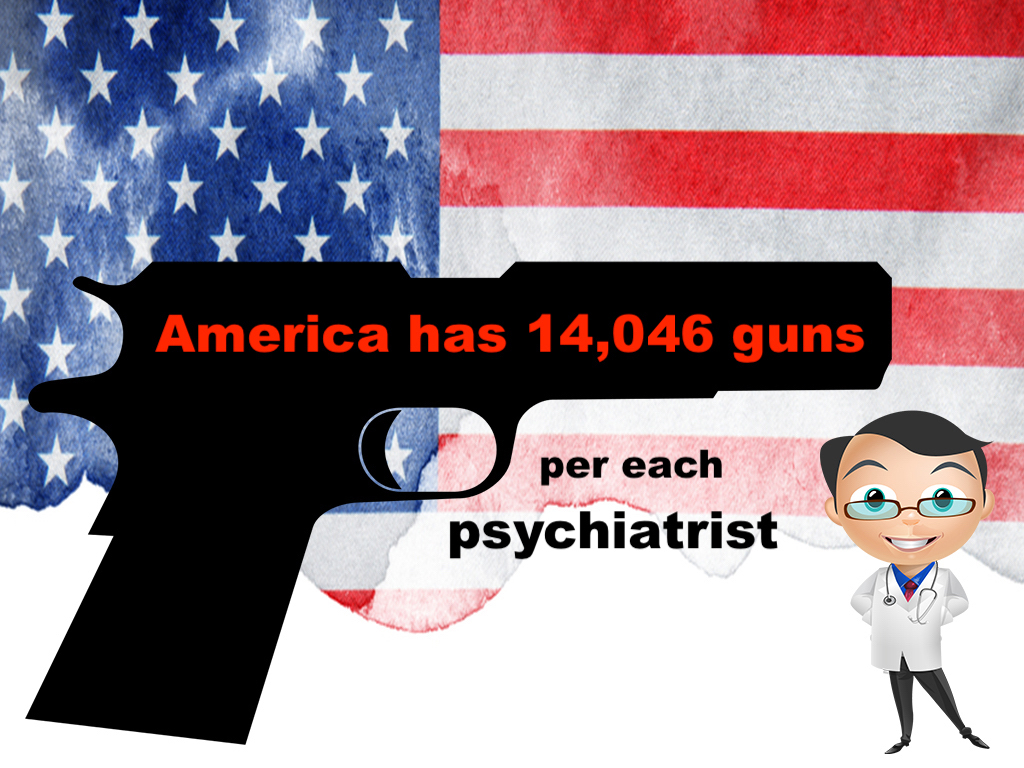

Physician suicide is a public health crisis. More than one million Americans lose their doctors to suicide each year—just in the United States. Researchers say we lose 400 physicians per year to suicide (they believe this is an underestimate), yet 400 is the size of an entire medical school. The average medical school has 126 students in each class, and so that’s an entire medical school equivalent of physicians per year. Due to all the secrecy and underreporting—even death certificates that are completed as accidents when they are self-inflicted—doctor suicides are often well hidden. A physician in family medicine has a patient panel of 2,300 patients. The average emergency medicine doctor probably sees even more per year. Simple math on 400+ times 2,300+ and you’ve got a million patients who’ve lost their doctors to suicide (and that’s not including student doctors).

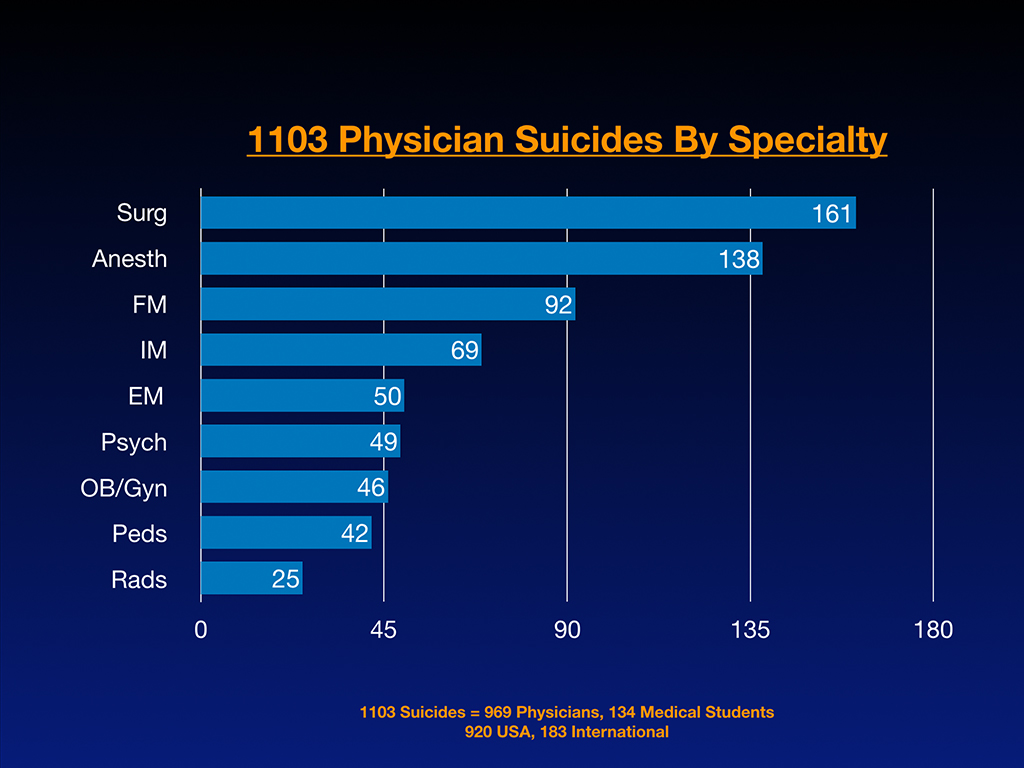

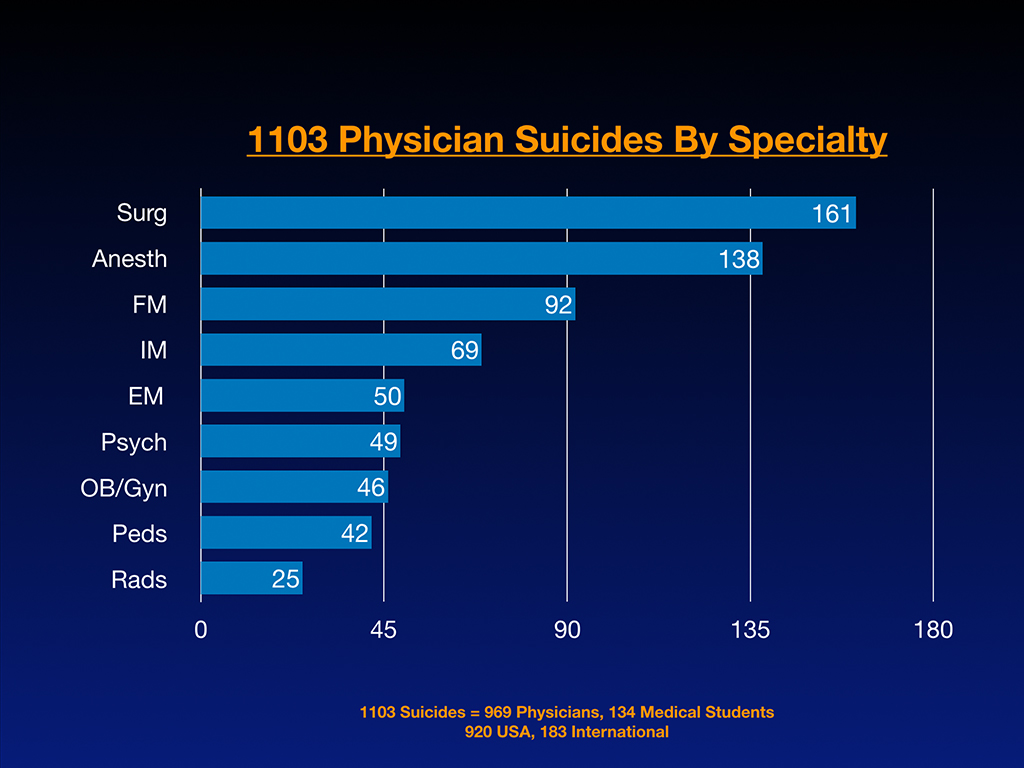

Here’s some raw data on more than 1100 cases I’ve received. Of 1103 suicides. 969 are physicians and 134 are medical students on the registry and 920 of these happened in the U.S. while 183 are international. People are contacting me from all around the world. Last week I was on a Skype call with a doctor form Israel telling me about the head of the department who died by suicide, as usual “happiest” guy and totally unexpected. When looking at raw registry numbers per specialty (and not accounting for size of specialty), surgeons are in the lead, then anesthesiologists, family medicine, internal medicine, emergency medicine, psych, ob/gyn, pediatrics, and radiology. However when evaluating these numbers based on active physicians per specialty we can see the real impact of suicide per specialty below:

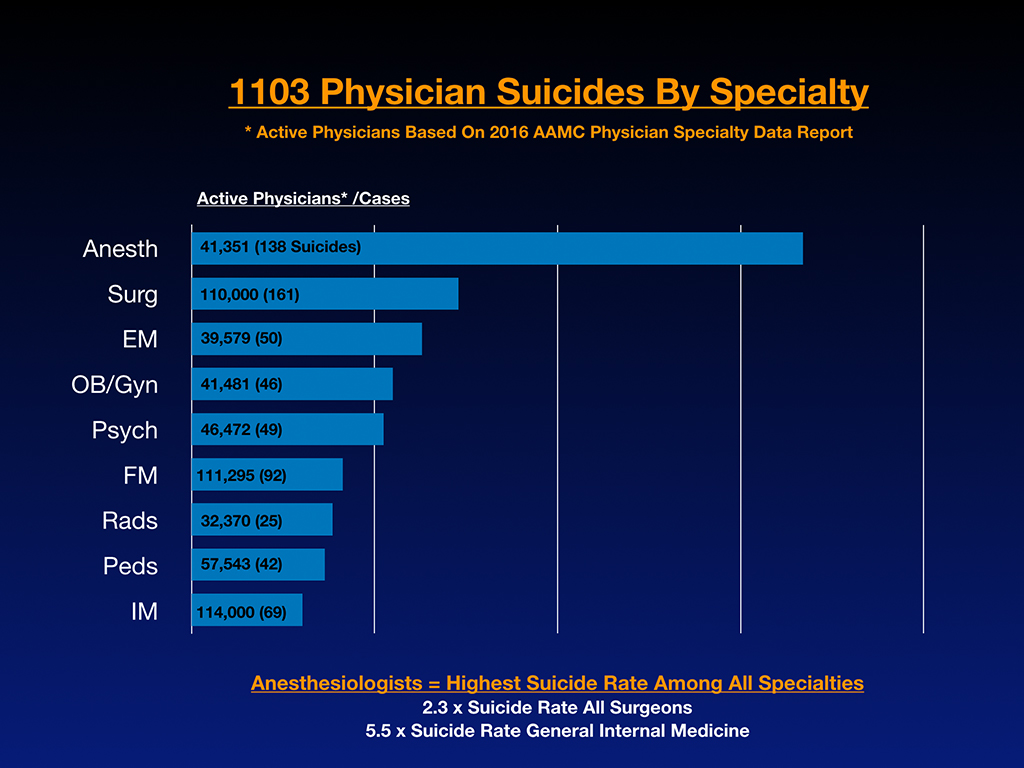

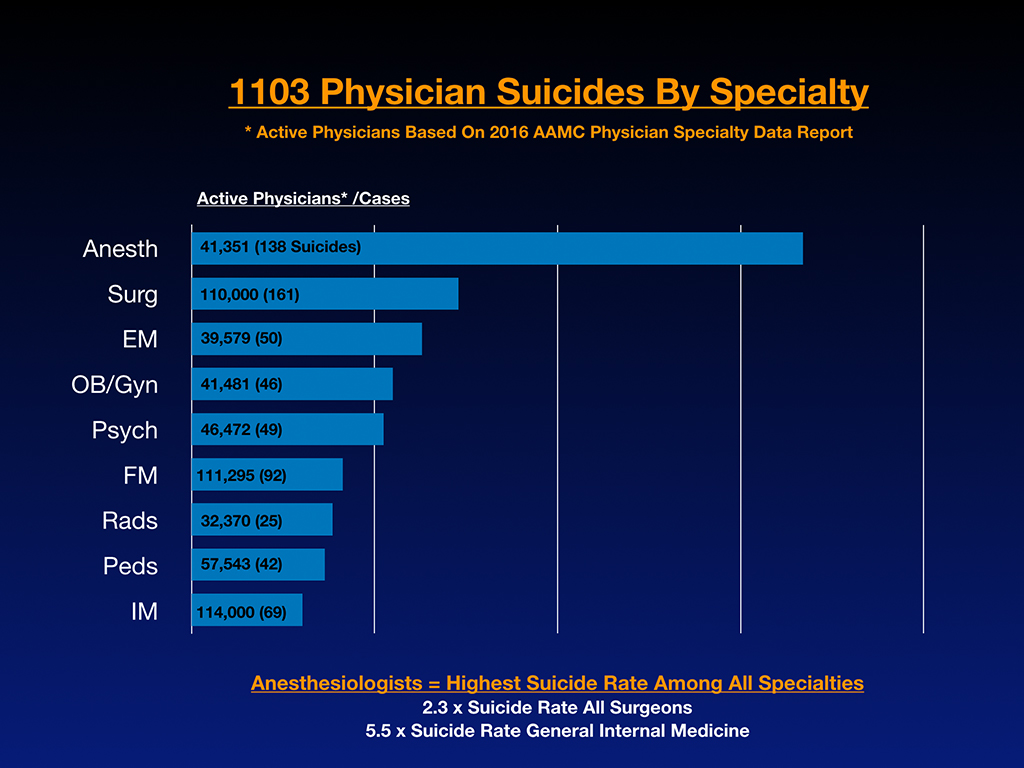

These are numbers based on active physicians in the largest specialties. Now we start to see some really interesting trends. Anesthesiologists are really off the charts. Of the largest specialties, general internal medicine has the lowest number of suicides according to my 1100+ cases. Anesthesiologists actually have 2.3 times the rate of suicide of all surgeons (general surgeons plus all surgical subspecialties). Anesthesiologists have 5.5 times the rate of suicide of general internal medicine doctors.

Medical students with preexisting mental health conditions deserve informed consent about mental health risks per specialty. I have premed students calling me who’ve had previous suicide attempts or panic attacks that are poorly controlled right now and they want to go to medical school. They deserve to know this information just for their own sanity and survival.

To fill in the gaps of this underreported epidemic, I’ll review 13 reasons why doctors die by suicide through case studies by introducing you to 13 our best and brightest colleagues who have died by suicide.

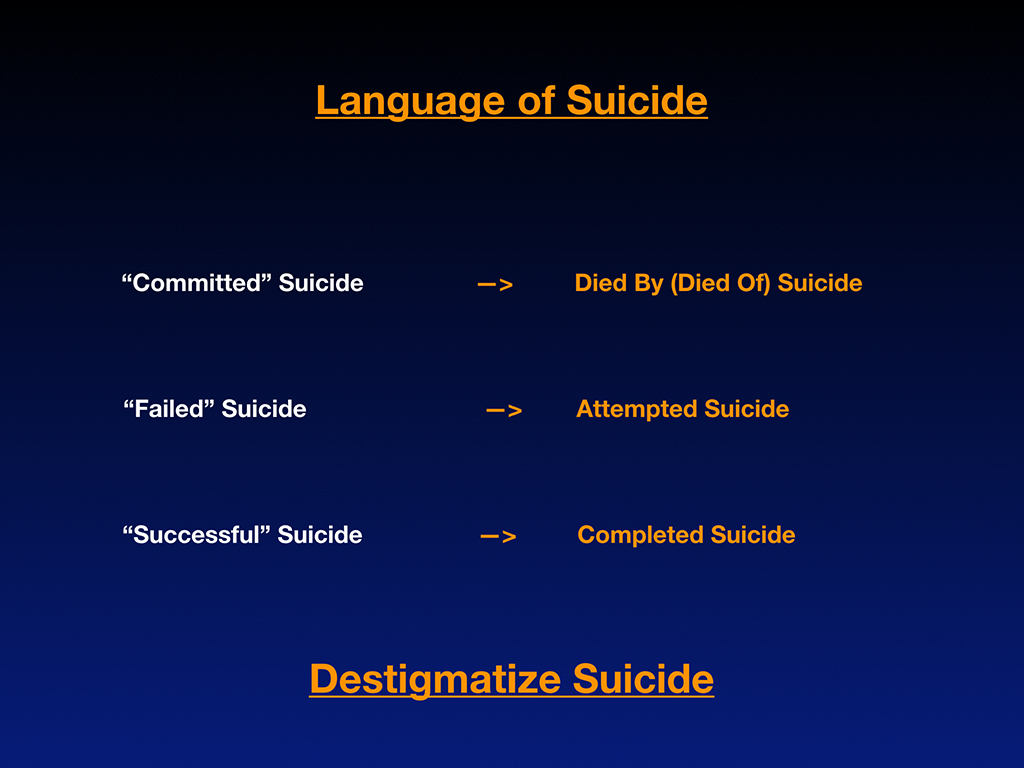

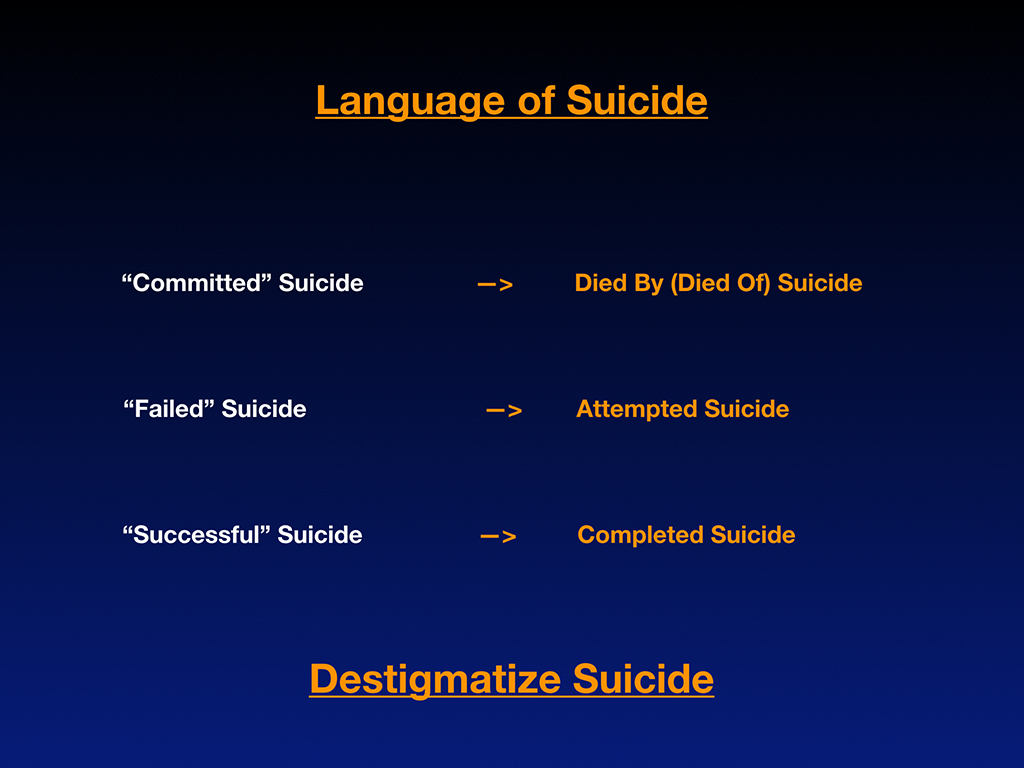

First, a quick recap on the language of suicide. Because this is such a taboo topic, people have been afraid to even say suicide aloud. By the way, at that memorial service that I went to they never said suicide out loud. Everyone knew that he shot himself in the middle of the day at Mount Pisgah in Eugene, so it wasn’t hidden. He’d had a public death in a public park, but nobody at the memorial service said suicide out loud. In the bathrooms and milling around, everyone kept whispering, “Why?” Everyone wants to know why and nobody will say suicide out loud. Imagine if we we were afraid to say diabetes out loud but we had to sneak into the bathroom to whisper about our diabetic patients. How far we would be with treating diabetics? Imagine if patients had to sneak out of town and pay cash and use paper charts to keep diabetes off the EMR. Insane. Right?

My plea here is let’s destigmatize suicide so we can actually discuss this crisis factually with data—and without such terror and shame. We can actually solve this problem. Because we don’t often know how to talk about suicide I’d like to encourage correct terminology.

“Committed” suicide is actually a very antiquated, stigmatizing way to discuss suicide because it makes it sound like a crime (like committed burglary or rape). Really suicide is a medical condition in which people are dying prematurely and should be discussed like every other medical condition—died by diabetes, died by heart failure, died by or of suicide. I know it’s hard because it’s like a knee-jerk reaction to say “committed” suicide. Even newscasters are still saying “committed” suicide, but I’ve been schooled on this through a psychiatrist who is the parent of a 29-year-old internal medicine physician who died by suicide. She was one of the first who commented on my blog Why Physicians Commit Suicide and she wanted me to know the title of my blog was stigmatizing. I didn’t know any better. I was just starting to discuss this myself and it was a great teachable moment for me, and so I’d like to pass that on to you.

Next, the idea of a “failed” suicide. How weird is it that when a physician attempts suicide and actually survives that should never be framed as a failure? Call that an attempted suicide in which we now have salvaged the person’s life by the grace of God. “Successful” suicide. To die as a 29-year-old internal medicine resident is not success. That’s a completed suicide which shouldn’t have happened in the first place. To prevent the next 29-year-old internal medicine resident from dying by suicide, I would ask you all to please destigmatize the suicide conversation.

Now I’ll share 13 case studies and 13 reasons why we’ve lost some very beautiful and brilliant people to suicide. I could talk about each of these amazing people for hours. Due to time constraints I’ll give just a thumbnail sketch of each case (some have been discussed in far greater detail in my other articles and keynotes).

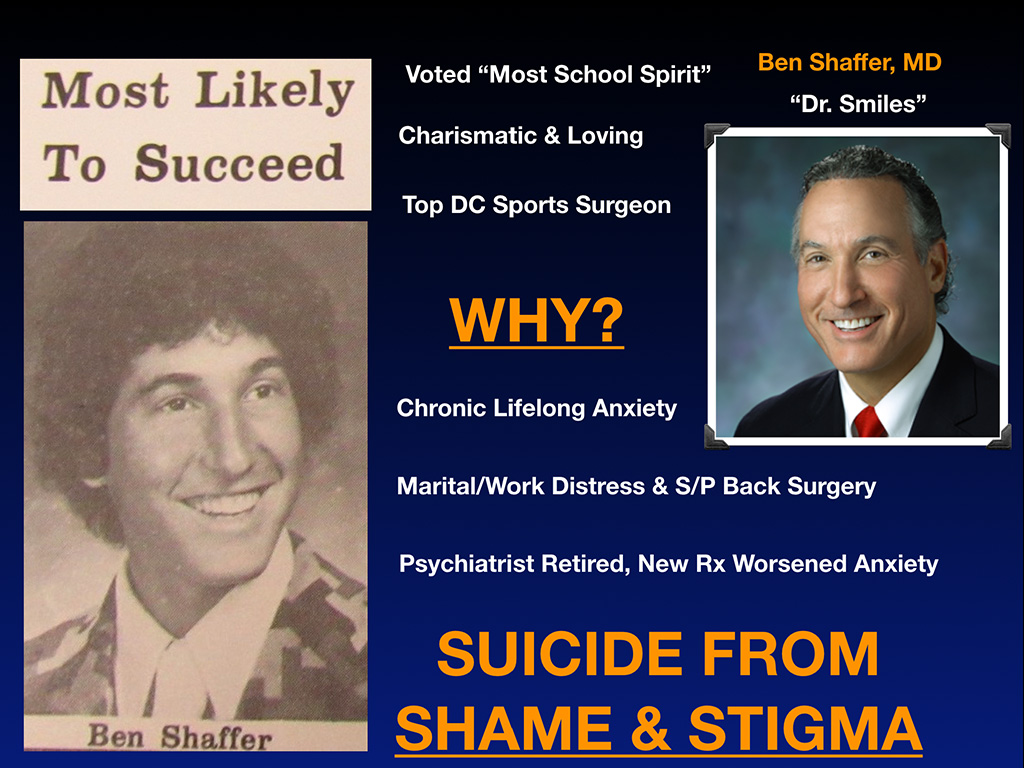

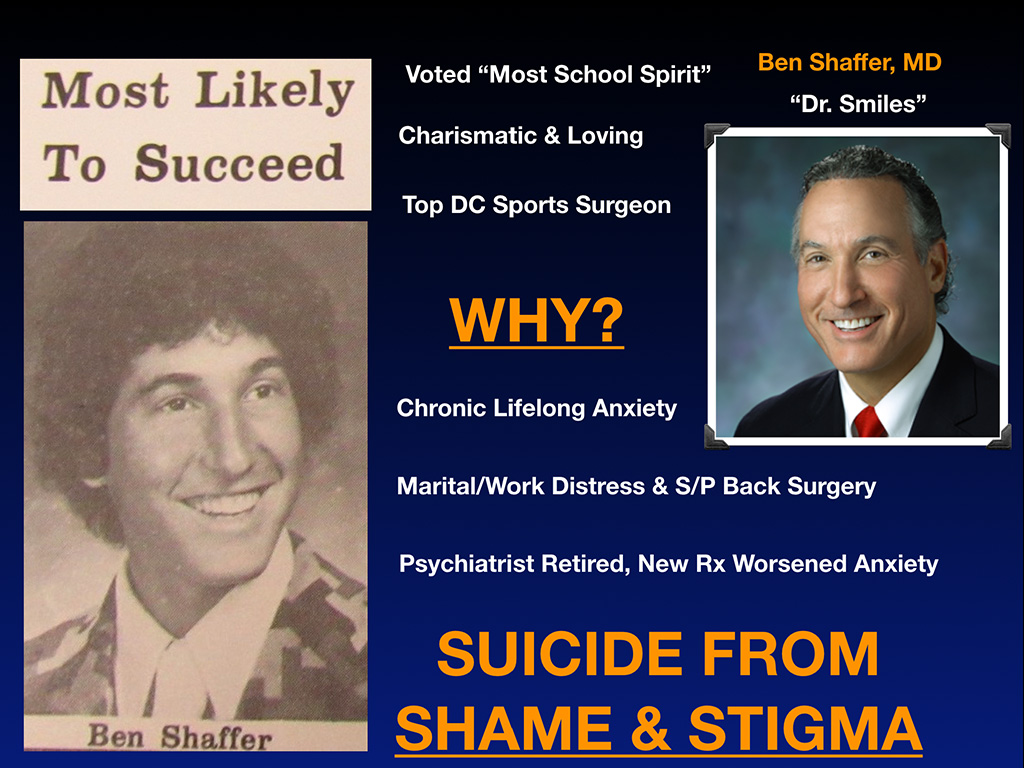

First meet Dr. Ben Shaffer. Ben’s sister just sent this newspaper clipping to me. Ben was voted Most Likely to Succeed in high school. That has a new meaning for her now. He was also voted Most School Spirit in junior high. You can see this guy is awesome, charismatic, loving. He was the top DC sports surgeon at the time of his death. They called him Dr. Smiles. Nobody had any idea he was suffering. Such a smiley guy cracking jokes up and down the hospital hallways.

Why is he now suddenly dead by suicide? Read more ›