Excerpt from a conference call tonight on how to fall in love with your medical records—just in time for Valentine’s Day! Download and listen in to podcast below or read transcript for a journey through the history of the modern EMR—with fun solutions!

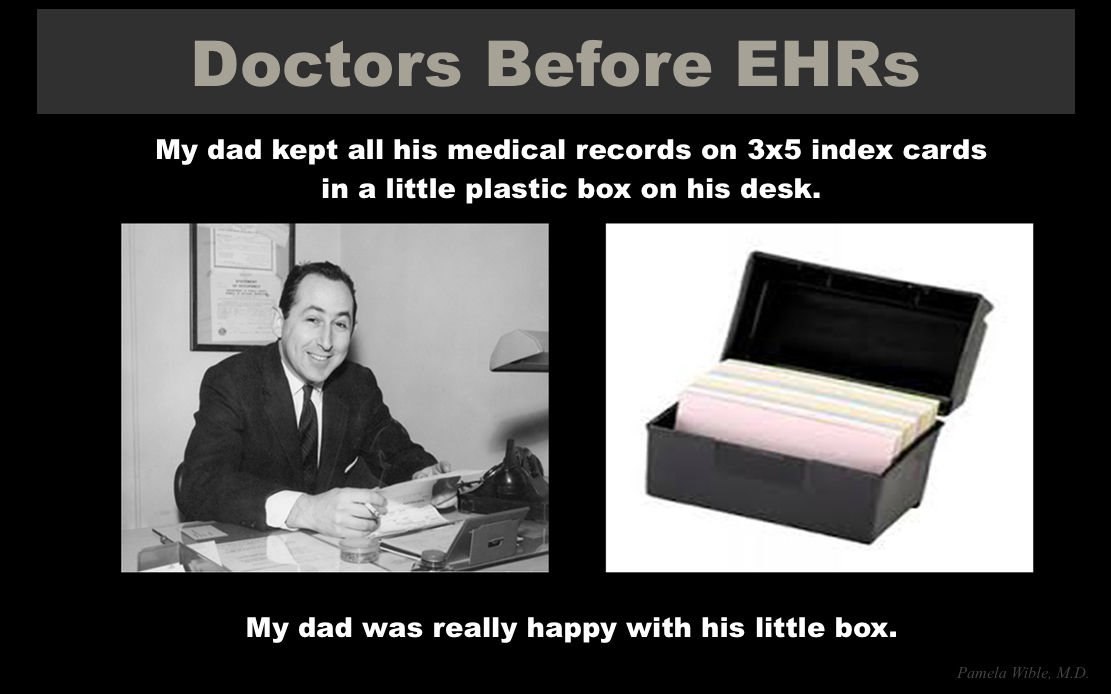

Once upon a time there was a doctor, a patient, and an index card. Here’s my dad and his box of medical records—all on 3 by 5 index cards in a recipe box.

Life was good. One doc with tiny handwriting—a man of few words—fit 30 years of a patient’s record on one index card. A friend told me she got an index card in some transferred records with 13 visits on the back and front of a 5 by 8 card and now she gets 8 pages from the podiatrist for an ingrown toenail—total insanity!

Need help designing your medical record system? Contact Dr. Wible here.

It wasn’t easy to separate doctors from their index cards. When an insurance company complained about his 3 by 5 cards, one old-time doc relented and switched to 4 by 6 cards. My dad always had his index cards with him in his shirt pocket—until his death, constantly taking notes (even during our phone calls!)

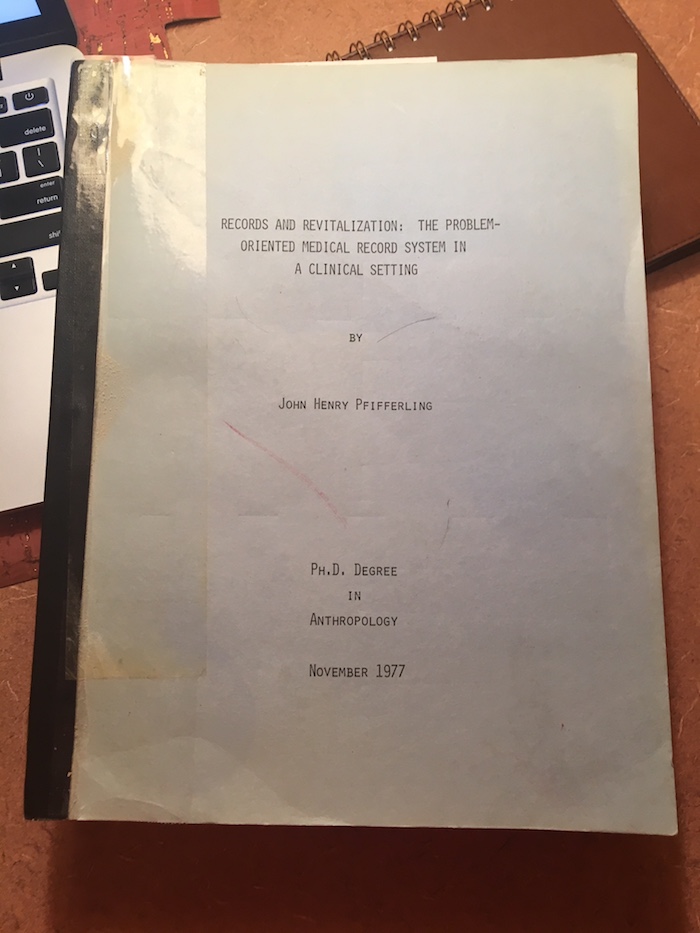

Don’t you wish you could have been a fly on the wall as they ripped the recipe boxes away from old-school docs and forced them to type on computers? Well, you’ll never believe this (and of course this would happen to me) . . .What are the chances that I would actually run into a brilliant anthropologist named John-Henry Pfifferling who actually followed docs around with a notepad for two years studying the index-card-to-computer transition? And he lived to tell about it!

As you might imagine physicians not only had resistance to EMRs but also to an anthropologist following them around taking notes on their behavior. The entire project was considered “too dangerous” because medicine just “wasn’t ready for anthropology.” Plus doctors and hospital admins found it difficult to believe that an anthropologist would actually be interested in modern cultures, particularly the profession of medicine and the transition to electronic records.

So I just read his 343-page PhD thesis from 1977: “Records and Revitalization: The Problem-Oriented Medical Record System in a Clinical Setting” that recorded the adoption of the problem-oriented medical record among practicing physicians.

Our current SOAP note originates from the problem-oriented medical record (POMR) and was developed by Lawrence Weed, MD for doctors—the only ones allowed to write in medical records back in the day. Weed’s hope was that the POMR would end chaotic, non-cumulative episodic and illegible medical charting—and lead to a new and exciting era in medicine—in which (fingers crossed) we could all work together. Imagine that!

Pros & Cons of Problem-Oriented Medical Record

Here are some of the advantages and disadvantage of moving into the electronic age with a uniform medical record system according to physicians interviewed in the anthropological study.

Advantages:

Systematic organization of medical data with problem-orientation rather than disease-orientation

Easily-accessed and complete problem list (that includes psychosocial)

Medical education reform—logical thinking vs. “tyranny of memorization”

More patient-centered & transparent

Uniform communication for teamwork (social workers, RNs can add to record)

Encourages honesty, continuity, and may weed out incompetence

SOAP acronym easy to remember

Legibility!

Disadvantages:

Forced segregation into patient problems fragments vs. whole-person narrative

Territorial loss of control by encroachment on doctor’s notes/orders

Leads to an “explosion of paperwork”

Reveals ambiguity in patient care

False sense security in titles of problems

Over-medicalization of life

Strong physician supporters trusted this charismatic leader, Lawrence Weed, MD, and his new model of organizing medical records—yet many doctors resisted. Surgeons were most resistant, the internists were ambivalent, psychiatrists demonstrated “damp enthusiasm,” according to the anthropologist.

Culture of Distrust

Most fascinating to me was the obvious culture of distrust in medicine generated by physicians themselves. Doctors back in the day displayed distrust of hospital administrators, nurses, medical students—and even each other! A few quotes from his thesis related to distrust of these four groups—bureaucrats, nurses, medical students, and physicians:

Physician-Bureaucrat Distrust

Ongoing tension between the entrepreneurial and autonomous physician and the bureaucrats has been present throughout modern medical history. Computerized medical records were welcomed by bureaucrats for the “systematizing, auditing, controlling potential” of doctors.

“One of the most common phrases that was used by resistant physicians was ‘the POMR is a conspiracy.’ When questioned further they indicated that it was a conspiracy by those in administration to function as administrators want them to: ‘pushing piles of paper around.’ It was also a conspiracy to ‘get the doctor.’ If the game was to get the doctor, then some requirement that everything must be documented would surely be a useful ploy.” (page 269)

Physician-Nurse Distrust

There was “polarization between doctors and nurses who could now question the logic behind a physician’s therapeutic plans on the computer so the ‘computer was voted out of the ward by a closed meeting of the senior medical staff” because it was “territorially unacceptable to those in power.” (page 80)

The “nurses’ SOAPed progress notes were renounced as “ungrammatical gibberish.” Physicians complained of “non-physicians ‘overstepping their responsibilities’ and were concerned about “who was in control of patient care, exemplified by satirical remarks on ‘nursing diagnosis’” The physicians in both the medical and surgical services spoke of the doctor-patient relationship as being “corrupted by nursing arrogance.” (page 250)

“Within days of the initial physician’s outcry, humorously characterized as ‘who’s writing in my notes?,’ several other physicians used the same ploy to denigrate the nurses.” (page 253)

Physician-Medical Student Distrust

Higher education is about learning and asking questions, yet I’ve found the medical hierarchy methodically oppresses medical students who may be discouraged from thinking independently or questioning their superiors. Some for the first time in their lives fear asking questions during medical training. Our trusted anthropologist writes:

“Within the U.S. medical culture, age, and concomitant status categories (medical student, extern, intern, resident, etc.), usually confer greater authority and greater power. As a medical student, the opportunity to affect peer and faculty behavior is minimal, and the well-documented passage from humanist to cynic occurs. Medical students are low in the professional hierarchy, and behave accordingly. For example, rarely do medical students display disagreement and displeasure to their medical school clinical faculty. As student physicians increase in age, credibility, and credentials they gain the right to assert their opinion. Innovativeness is not customarily rewarded medical student behavior. Only with the acquisition of clinical experience can the opportunity to innovate occur.” (page 145)

Physician-Physician Distrust

The anthropologist found that frequently physicians use “alienating humor” to converse with one another explaining that “much of the humor was at the expense of patients, at other specific physicians or services, at psychiatry or medicine in the surgical domain and vice versa, or commonly placed one physician in a subordinate position. (page 122)

“Internists rarely requested psych consults and had ‘disparaging remarks about the entire psychology and psychiatric services.’” (page 120)

“In medicine, the surgeons claimed that ‘heroic actions are rare in the medical service.’ The surgeons claimed that chronic care is the ‘ballpark of the internist.’ The internists criticized the surgeons as ‘one night stands’; ‘going in and cutting as spectacularly as possibly while we have to do the painstaking clean-up work.’ The ideological differences between internists and surgeons are well known. They begin in medical school, and are strongly reinforced in informal contacts between surgical and medical residents.” (page 253)

“Internists commonly described surgeons as ‘technicians’ and as ‘heroic princes.’ Surgeons referred to internists as ‘boy scouts’ and ‘pill pushers.’ I regret that I did not keep a systematic record of the insulting metaphors that were used by each department; the underlying feeling of division and competition was pervasive in the institution.” (page 141)

After reading the anthropologic study, most shocking to me was the resistance of physicians to befriend one another and how doctors actively attempted to “suppress physician friendships.”

“Many physicians had doubts about the strength, intimacy, and candor of their friendships. Often they mentioned that they worried whether non-physicians were friendly because of the security the physician offered those friends when they were in medical need. Some of the physicians, notably those in the surgical service, were quick to point out that they deliberately made every effort not to build intimate friendships with other physicians.” (page 121)

Of course the “attitude of the hospital’s administrative leaders were totally non-conducive to friendship formation.” complained physicians. (page 122)

So my question today is how is it even possible to create a uniform medical record system with so much animosity and distrust?

Physician Resistance To Innovation—A Paradox

I believe the origin of physician resistance to innovation is threefold: 1) Fear of change (universal among most people), 2) Territoriality and 3) Culture of distrust.

Our anthropologist points out “ . . . the medical record has traditionally been called the doctor’s record, and progress notes were labeled as doctor’s progress notes. If the record is to be considered the patient’s record and notes labeled as progress notes (with team participation), two areas of resistance can already be identified.” (page 261)

Medicine is conceived as “a discipline receptive to change—constantly and carefully evaluating innovations for better ways to help the patient. Paradoxically, any changes on the traditional doctor-patient relationship, on fee-for-service transactions, on review of medical care by non-physicians (or by peers), and on the demystification of medical terminology are fought vigorously.” (page 267)

On the one hand, the media reinforces “the desired self-image of dynamic medical and research progress” while “higher education is notoriously conservative and resistant to change”—especially in medicine. (page 268)

So that’s the backstory to electronic medical records. Now let’s look forward . . .

Why Medical Records?

The original purpose of a medical record was to simply record the patient encounter. The therapeutic relationship that flourished organically over time. Appointments were face-to-face with eye contact (no staring at a computer screen) and real conversation that allowed the doctor to get to know the patient’s philosophy, desires, culture, and address their medical needs in the context of their real life. Physicians back in the day could do that with no staff as a solo docs in a simple one-room neighborhood office—often right inside their homes. The record could be one sentence on one index card. Before hospitals dominated the medical scene, all records were primary-care outpatient-based and involved two people—doctor and patient.

Now the modern medical record has been overrun by so much complexity and competing interests that the doctor and the patient risk losing the very foundation of their sacred and healing relationship. The medical record system is a multi-page/multi-window experience that is often neither intuitive nor ideal for any specialty. Tertiary-care hospital-based record systems amass so much information from so many sources that sometimes what you are looking for can’t be found. So the SOAP note has turned into the APSO note so we can locate the assessment and plan amid all the crap entered by medical staff. Except maybe housekeeping, everyone seems to have the ability to add to this ever-more-complex medical record.

Medical records are now not so much used for the patient encounter but to document things done to the patient in ever-shorter visits with unreasonably lengthy documentation required for billing and coding in case of auditing or lawsuits. Of course, the sheer volume of material required for documentation requires more face-to-screen time with the computer than face-to-face time with the patient—and sadly encourages dishonesty and outright lying in the official record with boxes checked for questions never asked and entire sections cut and pasted over and over again on a bloated record based on distrust.

Doctors distrust patients who may sue them so the medical record expands due to CYA medicine and excess labs, tests (and additional documentation) increasing medical expense. Patients distrust doctors and don’t share what’s really on their minds (how can they in 7-minute visits?). Many patients have written me seeking help because their doctor profiled them in the medical record as a “drug addict” or a “bad mom” or “noncompliant” and they can’t get that phrase off their records. Even if they change doctors they feel labeled and experience discrimination. Let’s not forget these medical records are stored in the cloud and on systems that can crash and be hacked in a moment with all patient records and physician NPIs and social security numbers leaked to the world.

So if the truth of a patients life is no longer captured by a medical record due to distrust and bureaucratic bloat, what next? Meet some doctors who have actually fallen in love with their medical records

Welcome Your Ideal Medical Record!

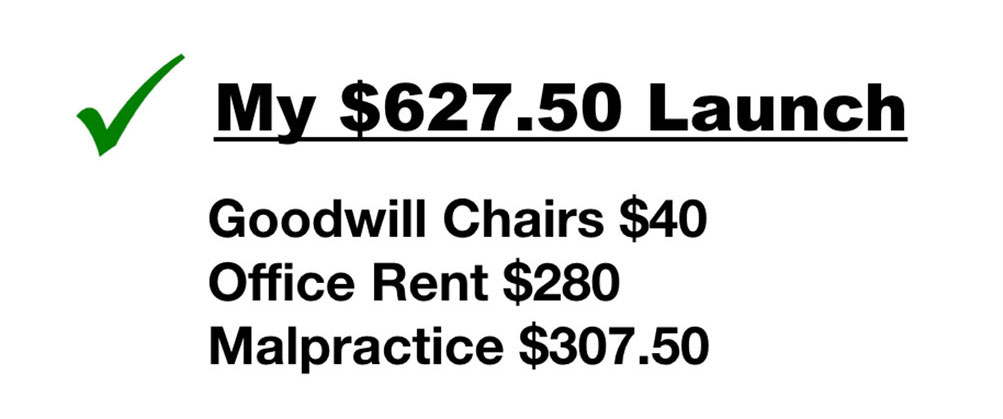

You can actually create an ideal medical record! I did nearly 15 years ago. Back in 2004, fed up with assembly-line big-box medicine, I launched an ideal medical clinic designed by my community. And I created my ideal electronic medical record! I originally intended to buy a real EMR, but while searching for a system, I started my own electronic records on my apple laptop and turns out the system I created with primitive text edit files (now on password-protected Pages files) was better than anything that I could buy! I accidentally created my own ideal medical record and have been practicing happily ever after since 2005 having spent nothing on an EMR! My IT buddy claims that my electronic record may be one of the most secure in the country! How ’bout that?

Since 2005, I’ve helped hundreds of doctors launch ideal medical clinics—and find or create ideal medical records that work for them. One part of the ideal medical clinic experience is to enjoy—even fall in love with—an ideal medical record. So I encourage all doctors out there who are struggling and fighting with a medical record system you don’t like to STOP—and do it differently. Rather than continue weird workarounds to be more efficient and play better with a flawed medical record system, I’m encouraging you as an independent, entrepreneurial physician to create YOUR ideal medical record—even if just a weekend science experiment. You can even go back to paper or index cards if you want! You are the boss. Do what’s ideal for you and your patients.

Four Impediments to Ideal Medical Records

1) Third-party intrusion that treats doctors as economic units and patients as widgets. 2) Competition among health systems that won’t do what’s in the best interest of the patient. 3) Infighting among doctors. Academic vs. community, tertiary vs. primary care, MD/DO vs NP/PA vs. ND so is it really possible to have a system that works for everyone? 4) Patient distrust. Ask yourself if your current medical record system allows complete trust and transparency in your relationship with your patient? Is your medical record in any way impeding the ability of your patient to disclose the full truth of their life experience? If so, you must change!!

Here’s how a great idea can turn into a shitshow. I asked several doctors, “What’s the most ridiculous thing you ever had to do on EMR?” 1) One hospital required progress notes to be dictated (could not be typed) into their horrific EMR. Notes would take several days to post, so most consultants (and even the primary team) had no idea what was going on with the patients. 2) Our EMR is a black screen with green print. 3) When I was working as an emergency physician, they switched EMRs. I was then told I had 1700 charts to complete which I had already done in the previous EMR. I refused to do this. They called security to escort me off the premises. 4) To dictate, have to use internet explorer. To prescribe have to use Firefox. So, to do one note have to use two browsers at a time. Frequently when saving what has been typed, I get a spinning wheel and then receive a message that there is an error and everything done is lost. 5) An gynecologist lamented a standard template that noted “gravid uterus” on every normal exam. She had to edit it to a default normal on every single note. 6) Family doc says: “Spent months doing stage 1 MU, correcting problems for EMR company. Finally switched to different EMR after much frustration then got audit from Medicare looking for MU screenshots from Old EMR which could not be done on read-only status. Wrote a letter of explanation and was told to pay back MU ‘bonus’ of $36K on top of the $75K we spent on IT support and staff time to be able to attest. Total loss over $100K not counting a year of my time away from my kids.” 7) Surgeon asks, “Isn’t the primary purpose of EMRs For the government to more easily track Medicare fraud?”

5 Ways Distrust Undermines Medical Records

As a patient, have you ever wanted a doctor to keep some things you share off the official medical record? Why? In one word—discrimination. Fear of discrimination makes comprehensive medical records a joke.

1) Pre-Existing-Condition Discrimination. “My entire GI tract was excluded based on one episode of stomach pain treated with antacids,” a friend reports. “Exclusions can go on for years. The Affordable Care Act greatly improved this, but if that were overturned?” he asks. Patients frequently request to use fake names or exclude diagnoses from chart. Genetic tests (like 23 and me) are done under assumed names (otherwise a gold mine for insurance companies to jack up rates). Doctors are often careful not to label a patient with a working diagnosis to prevent insurance company discrimination.

2) Drug-Use Discrimination. Due to federal government’s inclusion of marijuana as an illegal schedule 1 narcotic, even suggesting CBD oil can be seen as violation of regulations. In NY doctors say they cannot counsel patient to use cannabis products or any other schedule 1 under DEA regs or it’s a violation of their DEA license. Of course, any number of illicit and legal drugs are kept off the official record for a variety of reasons—including mental-health discrimination (see #4).

3) Sexual-Orientation Discrimination. Lesbian, sex worker, polyamorous relationships not declared to doctors leading to obvious difficulty is screening/risk reduction conversations and exams.

4) Mental-Health Discrimination. Physician mental health is a huge taboo for doctors. One physician writes:

“I’ve seen good friends denied disability and life insurance policies tiered to same as 1 pack per day smokers because of history of depression (even well controlled with meds). Coercive and unnecessary referrals to Physician Health Programs. Sometimes boards take away the physician’s freedom, dignity, even license. Agencies and some medical boards don’t differentiate between illness and impairment. They apply policies of the American Disability Act and HIPPA differently to physicians in the name of ‘protecting public safety,’ licensing agencies, corporate medicine authorities, and many other powerful bodies can mandate release of such information without even the slightest sign or evidence of impairment. One recent example is our physician ER colleague who had to fight 10 years for her license due to disclosing feeling the Baby Blues at work. discrimination SHOULD NOT and DOES NOT only apply to a few listed categories of race, gender. Discrimination due to one’s profession is also a type of discrimination that is not addressed enough when it comes to physicians’ rights.”

Veterans/firefighters/paramedics mental health is also an issue as it related to discrimination based on employment. The fear of denied benefits based on PTSD. Many will only talk off the record and away from prying eyes and ears…no paper, no pens, no electronic devices. Some have suddenly been fired after PTSD evaluations.

5) Legal-System Discrimination. Release of medical records to attorneys can cause huge problems so patients avoid disclosing their most intimate traumas. Workers compensation attorneys deny claims based on previous alcohol or drug use or experimentation. Medical records are a common point of attack in divorce, criminal, civil and child custody proceedings. A slip-and-fall case can lead to big disclosures in court displayed right on the big screen in front of 12 peers and anyone else in attendance (these court cases are public, by the way)

Dx: EMR TMI

“Our EMR’s are overly inclusive with way too much personal information on the summary sheet,” reports one doctor, “which can be viewed not only by other doctors but their nurses and nursing assistants and any one else who has to open your chart to take vital signs or document history. That’s a lot of eyes on your personal info. Curious staff can scroll through the whole thing right in front of you and make faces without realizing it and people talk.”

“My doctors at a clinic put my dependence on government housing in their summary of my medical history when referring me to another doctor,” says one patient. Another woman says, “I always laugh when I read privacy policies, knowing that they are lots of exceptions.”

Discrimination EMR Workaround -> Fake Names/Fake Charts

Doctor reports, “Our local hospitals routinely use fake names for VIPS and I have been asked to use a fake name to protect the patient from being shut out of life and disability insurance plans.” I personally know of medical students admitted under fake names for psych admits. How destabilizing is that for someone who is already having delusions? A psychiatrist reports placing “high-profile athletes” on fake charts with fake names and even keeping those charts with her and not left with other charts in clinic or on EMR when working corporate medical jobs. Patients request the use of fake names to order meds to avoid problems getting life insurance.

My Challenge to YOU—those of you no longer willing to submit to a system that is failing . . .

We are undergoing a transition in health care from centralization to decentralization, from tertiary care back to more primary care, from production-driven to relationship-driven care. Doctors and patients are not well served by big-box assembly-line medicine—it’s dangerous and unsustainable emotionally, spiritually, even financially. There is no way in the world you can deliver the kind of care that you dreamed of delivering to your patients in 7-minute increments while documenting on a computer system for twice as long as your face-to-face visit. I’m encouraging you all to think way out of the big-box. Your life is too big for your little cubicle. Your patients need the real you and your expertise. What medical record would allow you to create the ideal encounter in your ideal clinic with your ideal patients and help them heal?

I’m spending the next two weeks helping physicians create their most out-of-the-box ideal medical record for themselves that makes every patient encounter pure joy. I will report back our success!

My 3 Challenges For YOU. Ask yourself . . .

1) Should your ideal medical record be specialty specific? If you could create a specialty-specific medical record for your ideal clinic what would it look like? For your flow? For ideal patient encounters?

If you’ve ever felt that EMRs were created by people who according to one doc, “no fucking clue what your job is,” then why not create your own? If you don’t want to talk about blood pressures and arrhythmias and how many bags of NS given, and want to talk about mood, thought process and content, hallucinations, delusions, and suicidal thoughts, then go for it! What what would that medical record look like?

2) Is there a section/question you wish were in the medical record that is not? Maybe in contrast to the problem list, you prefer personal strengths and triumphs or a timeline of life events. Do you care about hobbies? Want to know what patients do for restoration and joy? Don’t want to limit social history to just tobacco and alcohol? You want details on relationships and abuse history, occupational and recreational exposures risk? Want a spiritual section or a diet history? Go for it!

3) Do you want to try paper charts? Lots of ideal docs in ideal clinics LOVE their paper charts!!! I really had no idea how many doctors I truly admire that are loving their paper charts in successful practices—and some still accept insurance! Create an ideal paper chart as a fun weekend science experiment.

Need help designing your medical record system? Contact Dr. Wible here.

In summary, we have a failed medical record system and slapping BandAids on something that is not working to try to make it work is not the answer. Maybe one of you innovators will come up with a med record that can be used by many more docs to bring them joy too! WE ALL NEED YOUR INNOVATION!

Now go have FUN! Then definitely share your successes! If you doubt that this can really be done, listen to these doctors who are living their dreams!

Join our fast-track and launch your dream clinic in less than 30 days.

You could do rat-race pediatrics, seven-minute visits with kids shoving needles in them.

You could do rat-race pediatrics, seven-minute visits with kids shoving needles in them.