BBC World Service Business Daily Report on overworked doctors

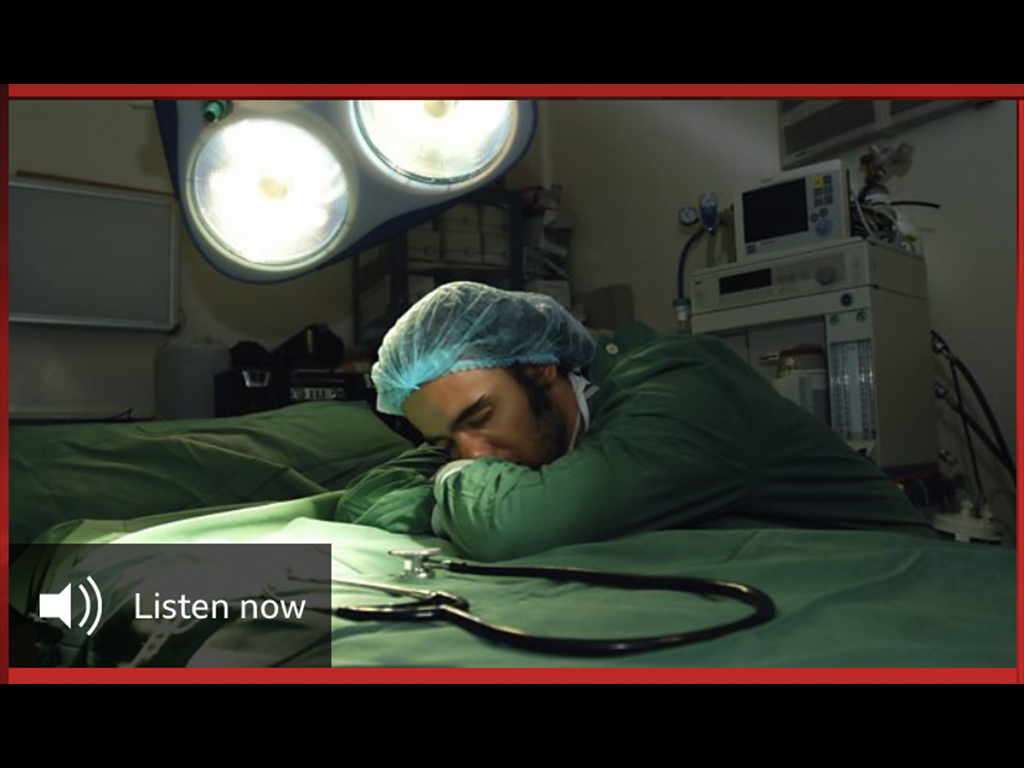

Dr. Yumiko Kadota: There was one day where I worked for about 20 hours, and the next day I was absolutely exhausted and I wanted to have a quick break and then return back to the operating theater. I wasn’t allowed to, the consultant said to me, “Oh, I remember working those hours as a registrar. It’s good for you.”

Vivienne Nunis: Exhaustion, depression, even thoughts of suicide, in today’s business daily with me Vivienne Nunis, I’m exploring the work pressures pushing some doctors to breaking point.

Dr. Pamela Wible: I saw medicine in its heyday, and I knew what a real doctor was, and that’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to do house calls and be the womb-to-tomb physician that you and your family members could trust for a lifetime. I actually became suicidal to the point where I did not get out of bed for six weeks, and I was just praying for my own death.

Vivienne Nunis: Medicine has long been looked upon as a respectable career. We trust doctors with our lives, and in return, we expect certain standards of care, but what if those doctors were under so much pressure and working such long hours their jobs became impossible, and yet they felt unable to speak out. Today we’re looking at the hidden problems in medicine, and asking what to do in any job where a culture of silence prevents bad practice from being exposed.

Margaret Heffernan: They’ve absorbed the hierarchy of the medical system, and they know that advancement depends on pleasing their seniors, which equals—don’t rock the boat.

Vivienne Nunis: Business Daily from the BBC.

Dr. Yumiko Kadota: I wanted to do plastic surgery since I was in high school, because I’d heard about a man who had had severe trauma to his jaw, and the reconstructive surgeons used a part of his rib to reconstruct it. I thought, “That’s something that I’d love to do, because it’s so creative.”

Vivienne Nunis: Thirty-one-year-old, Yumiko Kadota, spent six years in Sydney Medical School. After graduating as a junior doctor, she developed a passion for plastic surgery. By 2018, she was eight years into her medical career, working as a registrar, and hoping to be selected for the extremely competitive final five-year training course that would mean that she could work as an accredited plastic surgeon in Australia. But the pressures involved in pursuing that dream, left Yumiko traumatized.

Dr. Yumiko Kadota: So I would be doing mainly hand surgery at this hospital, as well as trauma to the face and elective skin cancer surgeries. The greatest demand was being on-call for 10 days out of every fortnight, and sometimes calls were coming in the middle of the night, and when I did get a phone call about a sick patient or any patient that a doctor or a nurse at the hospital was concerned about, I would get called back into the hospital.

Vivienne Nunis: So what kind of hours were you spending at the hospital by this stage?

Dr. Yumiko Kadota: So the contact hours were about 70 hours a week, and then on top of that I was on-call. So the typical fortnight was that I would be on-call for 180 continuous hours, and then I would get one night off, and then do another 80 hours on-call, and then I would get the weekend off, and then the two-week cycle would start again.

Vivienne Nunis: And how did that affect you?

Dr. Yumiko Kadota: Being on-call for 10 days means that there is a lot of mental unrest, and then eventually I started to notice a deterioration in my physical health.

Vivienne Nunis: And at this stage, you were spending a lot of time at the hospital, not just when you were working, but between shifts because there was just no point in going home.

Dr. Yumiko Kadota: If I would finish operating at three o’clock in the morning, I wasn’t going to drive home for an hour, sleep for an hour, and then drive back again, so I just ended up sleeping in a chair or a spare hospital bed whatever I could find. And there was one day where I worked for about 20 hours, and the next day I was absolutely exhausted and I wanted to have a quick break and then return back to the operating theater, but I wasn’t allowed to, the consultant said to me, “Oh, I remember working those hours as a registrar, it’s good for you.”

Vivienne Nunis: Yumiko raised her concerns with the hospital, pointing out that she’d worked 100 hours of overtime in one month. She suggested changes to the staff schedule that would have spread the workload more fairly, but senior consultants resisted the changes. At the end of last year, Yumiko wrote a blog post detailing her experience as a trainee surgeon in Sydney, the response was overwhelming. Medical students and health professionals from as far away as the UK, Poland, the US and Columbia contacted her to share similar tales of extreme pressure and overwork.

Dr. Yumiko Kadota: Though I realized that I had to remove myself from the situation if I wanted things to get better.

Vivienne Nunis: Did you feel at any stage that your own state of fatigue was putting your patients at risk?

Dr. Yumiko Kadota: Absolutely. I explicitly said, “I am concerned about my level of fatigue to the point where it might start affecting the care that I give to my patient.” You know, we’re not machines, we’re humans, and so anyone under that kind of duress could easily make a mistake.

Vivienne Nunis: You took the decision to resign.That must have been very hard?

Dr. Yumiko Kadota: It was something I dreamed about from when I was in high school, so to let go of your dream is a very difficult thing to do because often we attach our sense of self to our hopes and dreams, and becoming a surgeon was a huge part of my identity, instead of thinking of it as something I did, I thought of it as something that I was.

Vivienne Nunis: So you found yourself in a position where your health was so impaired, you ended up in hospital, but not as a doctor, as a patient.

Dr. Yumiko Kadota: That’s right. Yes it was very strange. Initially when my doctor suggested I go to hospital, I said no. It was because I just wasn’t getting better, it just got worse and worse. I was having problems with my sleep, and I was having flashbacks and traumatic symptoms, so I really was in a terrible place. I think it’s prevalent everywhere, and especially in Australia. The greatest response has been from people in Australia. I think it’s medicine’s dirty little secret. We all know how terribly the unaccredited registrars are treated, but no one really talks about it because these are the registrars who are still waiting for selection onto the advanced training program, so no one would ever say anything about it. We just keep it to ourselves.

Dr. Jason Lamb: I was also pursuing a career in plastic and reconstructive surgery, and frankly found myself just burnt out, and ended up deciding to give up on plastics. I was regularly doing 100 hours a week, and I was on-call for an entire year. I actually ended up being replaced by two and half people for that particular job. My boss said, “I’m not telling you to do these hours, but if you don’t, patients will suffer. But I’m not telling you to do them which really puts you in a really difficult situation.”

Vivienne Nunis: That’s Dr. Jason Lamb. Like Yumiko, he was a junior doctor, hoping to one day become a plastic surgeon. He too was put under enormous stress at a Sydney hospital where he worked.

Dr. Jason Lamb: You’ve got such a desired position and so few of them, and that power is held by a very few people. Yeah, we want to do these hours. We want to impress these consultants so no one will speak out, because if you speak out that’s kind of it for your career.

Dr. Jason Lamb: I remember the consultants sat us down and said, very bluntly that you have three chances to displease me, after that I will call the relevant consultants and make sure you never work in plastics again.

Vivienne Nunis: So how is it that bullying, intimidation, and impossible working hours became part of the deal in some parts of medical practice, and why are such harmful work practices allowed to persist?

Margaret Heffernan: So my name’s Margaret Heffernan. I’ve run five businesses. Ten years ago I started work on a book called Willful Blindness, looking at how it is that organizations make huge, often catastrophic blunders, and afterwards realize that all the information they needed to make a better judgment was right in front of them, but they somehow missed it.

Vivienne Nunis: Margaret has also written two plays about Enron, the US energy giant that collapsed in one of the biggest corporate failures in history, and it’s now a byword for corruption and mismanagement.

Margaret Heffernan: In the trial of the executives at Enron, the judge cited the doctrine of willful blindness, and I remember reading that and thinking, “Ooh, that’s a really interesting idea.” And at the same time, the banks started to collapse, and everybody said they couldn’t have seen it coming, and I thought, “Oh, come on. Lot’s of people saw it coming.” And this idea of willful blindness really stuck.

Vivienne Nunis: So it’s the same culture of staying silent in the face of such obvious bad practice also a problem in medicine.

Margaret Heffernan: If you lose one night’s sleep, which doctors routinely do, it’s the equivalent of being over the alcohol limit. We don’t let people drive like that, but we let them operate on us? In the United States, for example, physician-induced errors is the third leading cause of death. This is a big, real problem, and it’s about fundamentally human limits, which managements, and definitely finance officers and economists choose to ignore.

There is something in medicine known as the hidden curriculum which is, if you ask medical students when they start their training, “If you were asked to do something that wasn’t really appropriate. If you were asked by a consultant, ‘Would you do it?'” Most students will say, “Yes.” By the end of their medical training, more students would say yes. They’ve absorbed the hierarchy of the medical system, and they know that advancement depends on pleasing their seniors, which equals—don’t rock the boat. You also have to factor in to the fact that at the junior level, you often have people who have paid a very large amount of money, or their parents or their whole family may have paid a large amount of money for their training. Their family, especially in a first generation of medics, are unbelievably proud of their children. Taking all that education and throwing it away, it’s just, it’s too distressing for too many people that other people really love.

Vivienne Nunis: And also their sense of self, often this happens in many careers, is wound up so tightly in their profession that that’s also hard to let go of.

Margaret Heffernan: Yeah. And it’s a really good point, and it’s not just a sense of self, but it’s a sense of self as someone whom society regards as respectable, valuable. It’s a big deal to throw that away.

Vivienne Nunis: You’re listening to Business Daily, with me, Vivienne Nunis. Today we’re investigating the extreme pressure some doctors face as they try to build a career. We’ve heard from two doctors in Australia who’ve walked away from their careers in surgery. The next story you’ll hear is from a doctor in Hong Kong. He’s asked to remain anonymous, but he got in touch to explain that doctors there are required to work shifts in public hospitals that last 36 hours.

Hong Kong Doctor: I think everyone knows what you’re getting into as a doctor in Hong Kong. The 36-hour shifts are very well known, not just to doctors but to also to the lay people. There is a TV series called On Call 36 Hours. In Hong Kong the doctors are quite fortunate in that after their first year of internship, they get their full registration and they can go out to private practice. So a lot of people survive for that one year, then leave to private practice.

Vivienne Nunis: Practices like this, forcing new doctors to work so many hours, 36 hours in one shift, is actually driving doctors away into the private system.

Hong Kong Doctor: That’s definitely one of the issues.

Vivienne Nunis: And the problem continues.

Hong Kong Doctor: And the problem continues.

Dr. Pamela Wible: I’m Pamela Wible, a family physician in Eugene, Oregon. I’m also an activist in preventing physician suicide, and the author of Physician Suicide Letters—Answered.

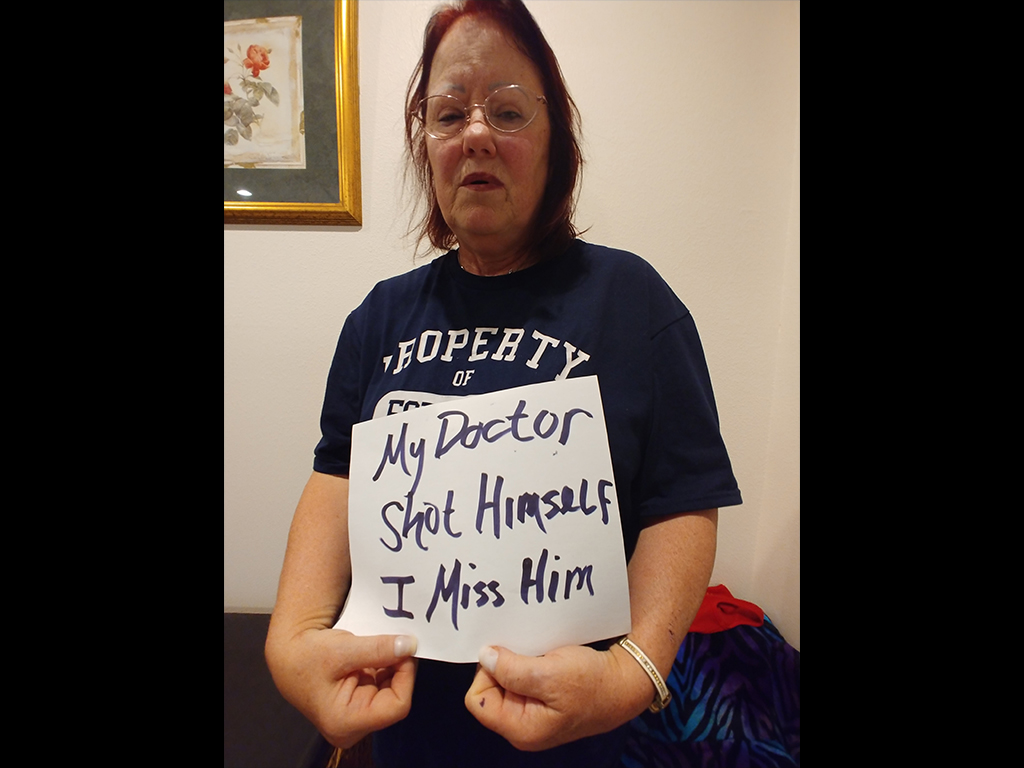

Vivienne Nunis: Dr. Pamela Wible is somebody who knows all too well how common it is for overworked doctors to be pushed to the brink.

Dr. Pamela Wible: I became suicidal myself in 2004. It was 100% occupationally induced. Both my parents are physicians, so as a child, I saw medicine in its heyday, and I knew what a real doctor was, and that’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to do house calls, and be the womb-to-tomb physician that you and your family members could trust for a lifetime. I actually became suicidal to the point where I did not get out of bed for six weeks and I was just praying for my own death. Every night I wanted to die in my sleep peacefully.

Vivienne Nunis: Dr. Wible realized she needed to step away, and she opened her own family practice based on old-fashioned doctor-patient relationships. Years later, as a number of doctors she knew were found to have killed themselves, she realized her own experience was far from unique.

Vivienne Nunis: She started a blog that led to her receiving cries for help from suicidal doctors all over the world.

Dr. Pamela Wible: Yeah, I feel like the suicide rate is accelerating. I would love to have the clear accurate data for this, but because it’s a taboo topic it’s not been tracked properly. So when I began to express myself through speaking, blogging and such, the floodgates just opened. The cascade of emotions flowing towards me from people, from all ends of the world, Pakistan, India, UK. Even in US, like truck drivers, and pilots, and such, if they wanted to, they cannot work more than 60 hours a week, there is a cap. That cap is placed there for safety, for the safety of the person driving the truck, flying the plane, and of course, everyone else on the highways and on the plane. You do not want the person at the helm being sleep deprived, and depressed, and suicidal, without treatment. So why are we allowing this to happen in our intensive care units, when our loved ones are on a ventilator, being treated by somebody who has not had sleep in several days, and is working essentially three full-time jobs?

Vivienne Nunis: So what can be done to prevent harmful work practices becoming the norm?

Dr. Pamela Wible: I mean I think it’s sort of a no-brainer, like we shouldn’t be treating people like this anywhere in the world. But in our hospitals? Not just in the type of care you receive, but the medical mistakes and your likelihood to die or even survive a hospitalization has to do with the mental health of the person who’s caring for you, and they simply are functioning on fumes, if we don’t re-structure our medication education system in a way that’s absolutely humane for everyone.

Vivienne Nunis: Author and expert on institutional blindness, Margaret Heffernan, says other industries have successfully stamped out poor working practices. Are there other industries, I’m thinking about banking perhaps, where this kind of expectation is put on junior members of staff?

Margaret Heffernan: Definitely, banking is one, but I think one that’s really striking because in all of my research, it’s the one that has made the greatest changes, is the aviation industry. Really for the last 30 years, there has been a huge effort to ensure that the industry as one, where the culture is what they think of as a speak-up culture. Anybody who sees anything going wrong, has an obligation—an obligation to speak up about it.

When, due to fatigue, or distraction, or overwork, or whatever, when a plane drops out of the sky, everybody notices that. There is an investigation, and the findings of the investigations are public. When a patient gets bad treatment on the whole it gets glossed over. It’s invisible. There are patients every day who get inferior sub-optimal treatment. When a patient dies, there’s some kind of investigation, but it isn’t a headline case. This isn’t hundreds of people dying, this is someone who was ill who died, and so it becomes kind of invisible in hospitals. It becomes a little bit invisible to the poor people working in these systems, and this is not that they are heartless, brutal people, but when this happens day-after-day, it isn’t exceptional, and so reacting to it as though it were exceptional, seems a kind of over-reaction, and so it becomes normalized, and that’s how it comes to be that people are blind to it.

Certainly sticking together is really important. You know, the doctor who wrote the blog post took a huge risk, and in general, I intend to advise people, if there’s an issue you want to confront, do it as a group, not on your own, because you’re really exposed if you just do it on your own. But I take my hat off to the people who do dare to raise it, because it truly isn’t that people don’t know. They’re getting away with it.

If you’ve have been a victim of human rights violations in medicine, have been overworked to the point of self-harm or harm to patients, please leave your comment (even anonymous) below, or reach out to Dr. Wible confidentially here.