VIEW FULL KEYNOTE above (including narrated slideshow)

In this closing keynote at Psych Congress 2019, Dr. Wible reveals the results of her 7-year investigation into more than 1,300 doctor suicides—and shares simple solutions to the suicide epidemic in an uplifting, life-changing, and surprisingly entertaining session. Warning: Though content is tragic, audience bursts into laughter more than 20 times during the first few faculty disclosure slides.

Dr. Rakesh Jain: This next topic of conversation we will have is obviously of great importance to you and me, otherwise you wouldn’t be here, that’s “Healing our Healers: Preventing Physician Suicide” and, you know, psychiatry is all about storytelling, is it not? That’s why we came into this field, so can I tell you a quick story about a 27-year-old intern in internal medicine about three decades ago? Would you be okay if I told you a quick story about this intern?

So a 27-year-old, first-year intern, three or four months into his residency was struck down by his second episode of depression, didn’t quite know what was going on with him, but somehow found a family physician, knew something wasn’t quite right. Went to see him, got put on imipramine, which was at that time, this was before there was an SSRI, but no therapy at that time, no understanding. No one actually asked him about anything, about suicidal ideas. Things sadly did not go well for this intern and he started really slipping into his depression and one night actually put out all his imipramine on the bed to decide what would be a fatal dose, how quickly it would work. Just heartbroken. That intern was me.

This is from a long time ago, 32 years ago, and from literally nowhere, for reasons I didn’t even know, it is a family issue. I was struck hard. I think it was because of a failing marriage and new stress. I went in next morning to my program director, handed him my beeper (at the time there were beepers), handed him my ID and I was three months into my internship. I said, “I quit.” I didn’t tell him why I wanted to quit, which was to end my life. I was wanting him to know that I was good enough, that I was giving him notice.

He though saw something. He made me sit down. He made me talk and I talked and I talked and I talked and he took me to the next door office, which was a wonderful psychiatrist who for the rest of my life, I will be forever grateful, and she took me under her care and talked about suicide for the first time. Things were, however, rough. I went back to work, she put me on new meds. They seemed to help work. I called her at 8:00 in the evening. This is to tell you how grateful I am to you—psychiatry and psychotherapy. This is not a sob story. This is actually an optimism story.

I was crying my eyes out. It was 8:00 in the evening. I was on call. She drove over to the hospital, asked me to check into a hospital. Things were bad. I wasn’t psychotic, but I wasn’t that far from it. Then she said, “Okay, we’ll meet in the morning, we’ll decide.” What I didn’t realize is she was writing up the paperwork to commit me. Next morning, we met 8:00. I was still on call, so I just walked in my fatigue and I don’t know what the matter was but I was a little more optimistic. I think it was the human connection with her. To know someone who cared that deeply was profoundly helpful.

She did not commit me. I actually, by the way, didn’t find out that I was to be committed that morning at 9:00. I didn’t find that out until years later, but things turned around. But what turned it around was actually this profession. It was psychiatry. It was psychology. It was their desire to heal the healer. My gratitude to psychiatry is never ending. So, you guys, you not only help your patients, we often help each other.

So we’ve been talking about suicide very openly at this conference. It actually has come to visit us. I am someone who’s had lived experience with it myself. So we wanted to have a real expert come talk to us and we found Dr. Pamela Wible, who will be here in a minute, and she has a very wonderful resume that I would like to read to you, but at the end of the day, what she’s going to tell us is her experiences in helping other physicians recover.

Our risk is very high, really it’s high. Male, female, doesn’t matter. Nurses, very high. Nurse practitioners, most likely, MDs, psychiatry is high so we have a real expert. Sadly there’s a lot of me out there in psychiatry, in medicine, and we need to heal the healers.

Dr. Pamela Wible is a family physician born into a family of physicians who had the great insight to tell her not to go into medicine. She had the great desire to completely ignore them and come into the field and she got fed up with assembly-line medicine. She has had town hall meetings where she invited the citizens to help create their ideal clinic. Wow! Ask the customer what they want? Pretty weird idea.

Since 2005, she has had an innovative model that sparked a populist movement that has inspired Americans to create what are now called ideal clinics worldwide. She’s helped more than 500 physicians and clinician launch their ideal clinics. I’m assuming you’ll talk some about that, Pam.

But here’s why she’s here—when she’s not liberating doctors in this way or treating her own patients, she devotes her time to medical student and physician suicide prevention. She has investigated more than 1,300 doctor suicides and her extensive database and suicide registry reveals high-risk specialties and solutions. We are a high risk specialty by the way.

Dr. Wible runs a free doctor suicide hotline and has helped countless medical students and physicians, and I’m assuming other specialists, heal from anxiety, depression, PTSD and suicidal thoughts. Named 2015 Woman Leader in Medicine, Dr. Wible’s pioneering work has been featured on most major news outlets, The Washington Post, CNN, ABC, CBS, and NPR. She has delivered two truly outstanding TED Talks. I’ve heard both of them, watched both of them, and is a subject of a new documentary Do No Harm, a film that exposes the silent epidemic of physician suicide.

Think we made the right selection? We did. Let’s talk about “Healing our Healers: Preventing Physician Suicide.” Pamela, please come over to the stage.

Dr. Pamela Wible: Wow! This is amazing. You all are the survivors, the ultimate survivors of a week-long conference. Give yourselves a hand. I would also like to thank Dr. Rakesh Jain and thank this entire team of Psych Congress for putting this amazing event on. I’ve met some of the most incredibly brilliant people on the cutting edge of mental health and psychiatry and so I would like us to please give them a round of applause.

View rather hilarious full disclosure video above on full screen for full impact.

Full disclosure: I am not a psychiatrist. I want to make that clear. Some people think I’m a psychiatrist because I’ve devoted most of my life to mental health care. My mom is a psychiatrist, though. Has anyone in here had the great fortune to have a psychiatrist as a parent? One. Who has had the great fortune of having physician parents, one or both physician parents? Wonderful. Both my parents were physicians as was shared earlier.

So literally, I had to be an expert in physician psychology to survive my childhood. What’s interesting, there’s only one person that might have had this shared lived experience with me—the gentleman in the front row who also had a psychiatrist as a parent. My mom, a psychiatrist, did this interesting thing (it only happens with psychiatrists, I don’t think any other children have had these experience) my bedtime stories came from psychiatric journals.

She was in residency when I was just really little, and you know these needy kids need so much of your time and she’s got so much of her time devoted to listening to her patients. You know, it just makes sense to multitask. Right? So she would read the psychiatric journals to me and every time she landed on one of those pharmaceutical ads, she would stop and she would tell me to analyze the woman’s face.

These are 1970s Valium ads. Anyone have the great privilege to see one of these? Usually like really freaked out housewives. Right? She had me staring at them and she would do what Dr. Rakesh Jain suggested we do at breakfast this morning, which is look at the face of the person on the screen and not just look at the face—figure out the mood of the patient. These are the questions my mom was asking me when I was like two. So I got really good at analyzing people’s faces, and to the point where in high school I’m on a city bus, and my boyfriend’s like, “Stop looking at people that way!” It really is disturbing to other people who weren’t used to analyzing people’s faces in public.

Yes, let’s see, a few other things I want to share. This is a very brief one-line faculty disclosure (on the slide above), I want to give you the FULL disclosure. You’ve heard about full disclosures? I’m an open book. I don’t want to hide anything. I want you to understand who I am, what I’m talking about, and we’re going to have a really interesting conversation here and by the way, there’s no Q&A after my talk, but I am devoted, after the wrap-up, there’s a 15-minute wrap up when I’m done but afterwards, I will stay in this room till the last person leaves, answering any and all questions that you have. If you have to run out in the middle of my talk, because your flight’s leaving, IdealMedicalCare.org is my website. I return every single email, every single phone call, so your question I guarantee will be answered whether it’s here with the group or later.

So the problem that happened for me is when I entered medical school, I loved every specialty. I loved it all, and so it was hard for me to pick what to do because I didn’t want to exclude any organ system, any gender, any age, and so I managed to fall into family medicine. I went to this wonderful residency that had a behavioral health track, because you might not know, but there’s sort of two types of family medicine residencies, the ones that are very procedure based. You know, they train you to do C-sections in Alaska, that sounds terrible, or you could do like behavioral health, which seems much safer and easier for somebody who’s had my training with my mom and the psych journals, so I chose that route.

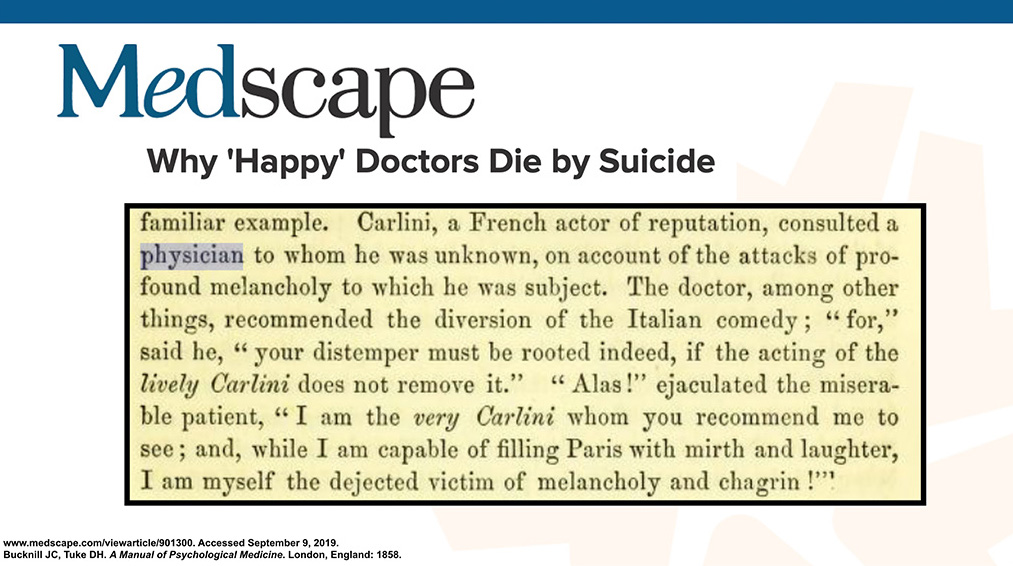

That’s the first full disclosure. I have four that I want to disclose. The second one is that I am sort of one of these “change-the-world” type people. Like the big picture system thinker and I have been accused of being “too happy” and also grandiose. This is by other psychiatrists, you know, online and such, and I think it’s because I have this unrealistic optimism, according to some people, about solving a centuries’ long suicide crises. This has been going on since 1858, you’ll see in my slide when the first reports came out that physicians had a higher suicide rate than the general public.

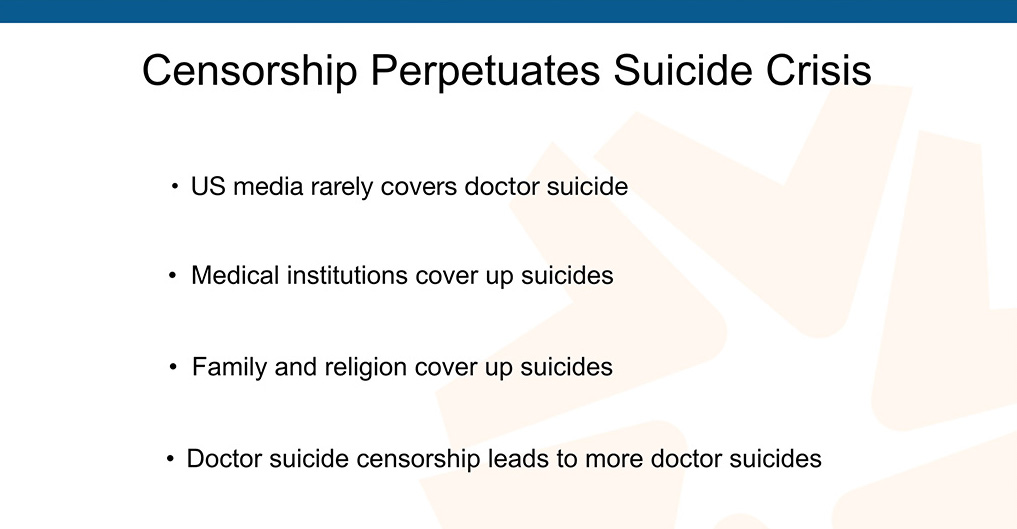

I’m very optimistic, excessively optimistic, about solving this. Now that I have the data, which I’m going to share with you, I feel like we can actually solve this because this is a problem that unlike Ebola or something where we have to like create a new drug or create something, figure out the human genome. The problem with suicide is really that it’s been a secret. Suicide isn’t really the problem, the problem is the secrecy. Once the secrecy can stop, and the stigma ends, I absolutely believe that we have the brain power, just in this room to solve the physician suicide crisis, if we stop hiding it.

I’d like to know how many of you by a show of hands know of a physician or a medical student who has lost their life to suicide? So most people in the room, and how many of you by a show of hands would like to end this physician suicide epidemic? Everyone. Great. I’m going to show you how in three easy steps. It might seem too easy to believe, but I’m excessively optimistic that it will work.

The third, I’d like to give you a full financial disclosure about who I really am and how I earn money because I’ve been accused of making money from human suffering. Now most doctors make money from human suffering, that’s sort of the business we’re in. If you’re not making money from human suffering, raise your hand. No hands in the room. Thank you.

I wanted to just really share how I do this. For seven years I’ve been running a free suicide helpline for physicians, and I’ll tell you how this came about in a little bit, but how I do this is I actually have this amazing clinic designed by my patients and community. They wrote my job description for me so there’s no like invisible tug of war in the room, we all are aligned in our intentions and goals and so I’m over here in my family medicine clinic, you know, where I like to work in my cute little Eugene, Oregon neighborhood and I do like ingrown toenail procedures and Pap smears and rectal exams. What else do I get? Acne, you know all this bread-and-butter family medicine, and I make all this pile of money over here, right, that supports my humanitarian free stuff that I do with doctors over here.

Because I’ve never charged any medical students or doctors for anything, any help that I’ve given them and so I run this suicide helpline and because I’m late night West Coast person and there’s a lot of people freaking out at like 1:00 in the morning in New York City and they’re residents. They call me. They don’t feel safe to necessarily tell their colleagues in their hospital that they’re having a meltdown, but they’re like, “Maybe I’ll call Dr. Wible in the woods in Oregon,” and since I’m usually up at 2:00, 3:00 in the morning, I end up on the phone for a few hours with residents on the East Coast.

The interesting thing about this is so I might be on the phone anywhere from five minutes to two hours with some people. Sometimes they call from unknown numbers, and one woman called from an unknown number and all she did was sob on the phone with me the whole time. Never gave her name, I don’t know if she’s alive. I don’t know what happened to her, but I just kept talking because you can see, I can fill up 75 minutes pretty easily, and I was hoping that something I said might click, right, might help her.

What I do with people when they call me, some of them feel immediately better because they were able to share their story for the first time with a colleague, without feeling like they were going to be turned over to the medical board, or get in trouble or lose their job. Some people email me, and they say, “I feel better just writing this email to you. Don’t even worry about calling me back.”

Great, and some people do need to see a psychiatrist, so of course I refer them to a real psychiatrist, not a family doctor who lives in the woods in Oregon, dealing with ingrown toenails. I do the best I can with the knowledge that I have. I have a whole group of psychiatrists that I refer to. If anyone in here specializes or would like to specialize in treating your colleagues, please let me know. I would love to refer people to you because there are people in all different states who need help.

The lovely thing that has happened as you heard in the introduction, since I have on the side, sort of helped other physicians launch independent practices, many of those are also psychiatrists who’ve launched independent practices specializing in physicians. So now I have like all these wonderful people who I know very well to triage people, too. That’s sort of how I make money. I just want to be completely transparent. I’m not funded by a drug company. I’m not aligned with any organization. I think that makes people feel nervous.

“Wait, she’s not at Stanford. She’s not aligned with any institution.” She’s a free spirit just running a suicide hotline without any permission from anyone. So that probably makes people feel a little unnerved. Right? Okay, I want to share more.

Full disclosure: the last little piece I want to share is that I do have critics. There are people that absolutely disapprove of the fact that I am running a suicide helpline, that I am doing this research and that I’m an activist in preventing physician suicide and there’s sort of a group of haters online in closed groups where I’m not invited that like to like put vomiting emojis up when they see my name and all sorts of things like I don’t know, (and a lot of these sadly are female psychiatrists). Like this was leaked to me in the last 24 hours. Somebody sent me a whole screen shot of all these things like, “How could they have her at this conference?” and I just want to apologize to Dr. Rakesh and if you’ve been pulled into this or Psych Congress in any way, if I have marred your reputation, I am so sorry, but I’m going to do a good job here and hopefully you’ll learn something.

The other thing, I just want to say, there’s many things they’re critical about. In fact, I have a whole spreadsheet. My plea: don’t kill the messenger, listen to the message. I’m sorry I’m not a board-certified psychiatrist. I’m a family physician with a good heart. I’m a truthspeaker, like that’s the thing that’s probably most important to me. I’m just absolutely against censorship and so pro-truthspeaking, and I think that’s where the healing comes from, and this is by the way, not a choice for me. It’s like having brown eyes. It’s not a choice for me. I was born this way. Some people say, “Oh, this is courageous.” This is, have nothing to do with courage, bravery, this is like I have brown eyes, and I tell the truth and I can’t help it. That’s just who I am. I can’t lie.

Before I go to the next slide, I just would like to share with you that you have a choice. I didn’t have a choice. I have to tell the truth, that’s just who I am but you have a choice as audience members. You have a choice whether to believe what I’m saying. If you don’t like what I’m saying, you can leave. If you want to stay and clap, you could do that. If you want to email me later. I want to give you the choice to do whatever you need to do, because this is a difficult topic. I will try not to trigger you, but I am going to tell the truth.

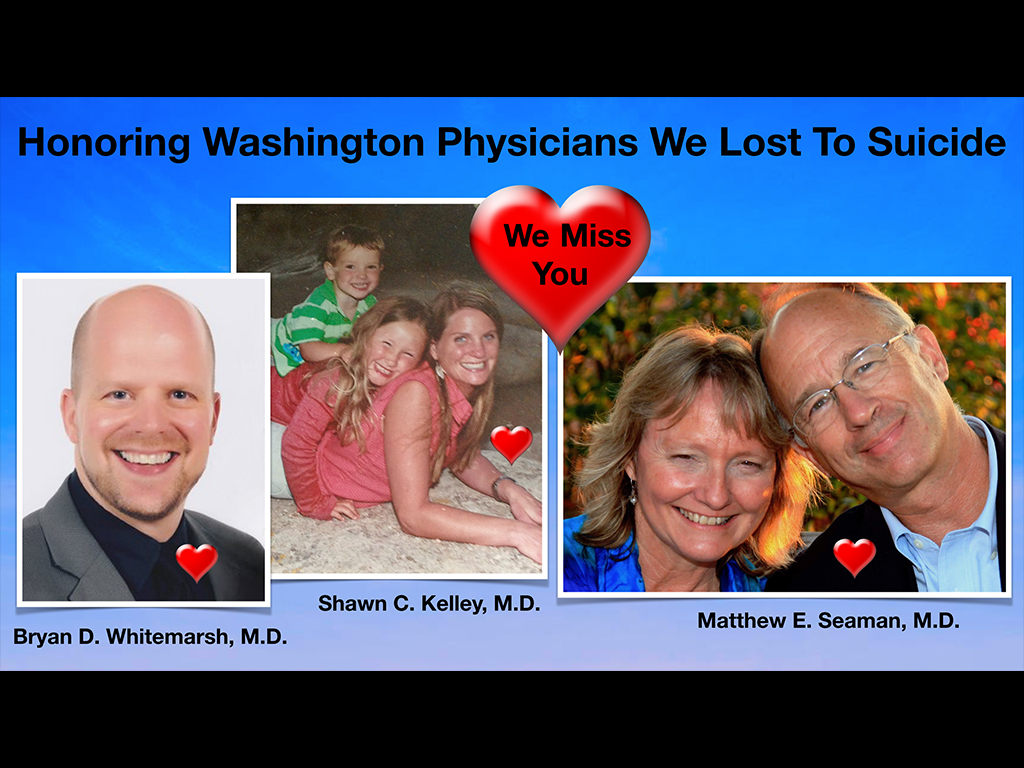

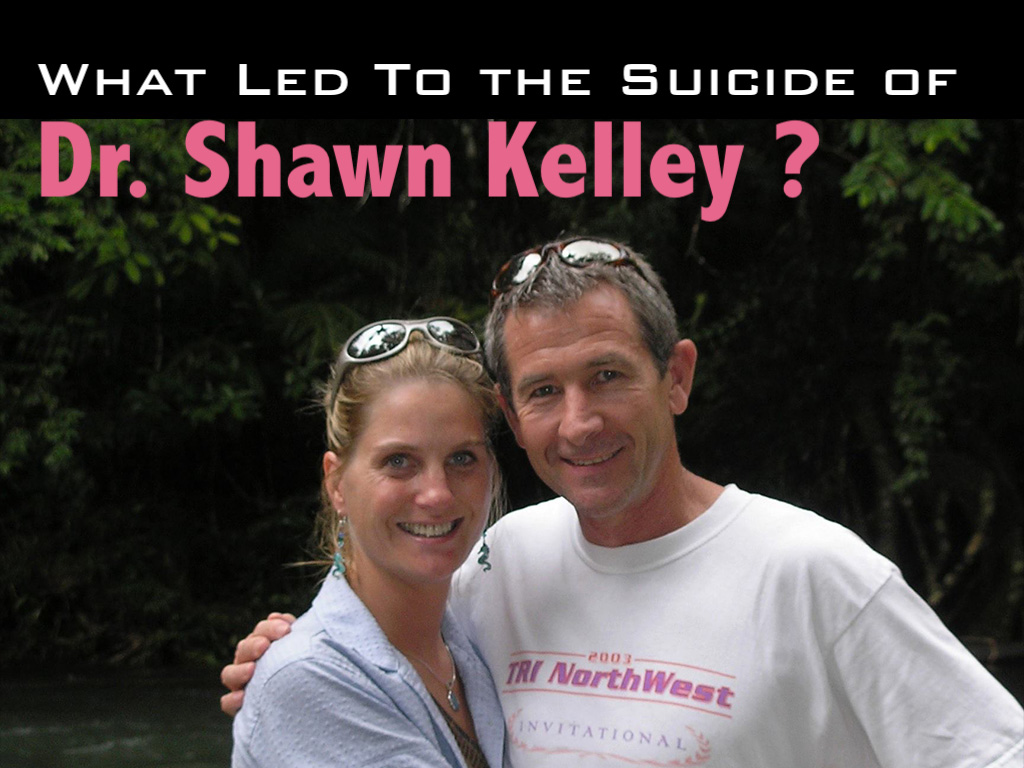

A few more disclosures here, the most important one is that as is typical of my behavior, I have permission from the surviving members of these physicians’ families who died by suicide who I feature in this presentation to share their stories. In fact, many of them are honored that I’m celebrating their loved ones. Some of them have reached out to me and before I even knew they existed or lost the family they’ve read parts of my blogs at their family members’ memorials and funerals overseas.

I’m going to introduce you to a few people that are really interesting in here, but I want to start with some learning objectives. Today we’re going to review why physician suicide is a public health crisis. We’re going to identify highest-risk specialties, discuss, why doctors fear seeking mental health care, and I’m going to describe three very simple ways that we can all destigmatize physician mental illness.

Before I move on to the first slide of the presentation, I have a request. One of the things that others are so critical of me about is my support of nurse practitioners and other professionals in medicine and so I know many people here, there are psychiatrists, there are nurse practitioners. I met lovely psychiatric physician assistants and psychologists and my request is: can we please stop the turf war between health professionals so that we can work together? We have a public health crisis and people are dying.

If you can prevent a suicide I don’t care if you’re board certified, I don’t care if you’re a medical student. I really don’t care whether you have a diploma or not. I’m just please asking for you to honor and love one another and let’s truly work together as a team to stop the death, to stop the needless suffering, so thank you.

These are our brothers and sisters in medicine, we are brothers and sisters in medicine and nursing and we are family, like you often hear during this Psych Congress, they refer to us all as a family, and I want you to take that seriously. We are family.

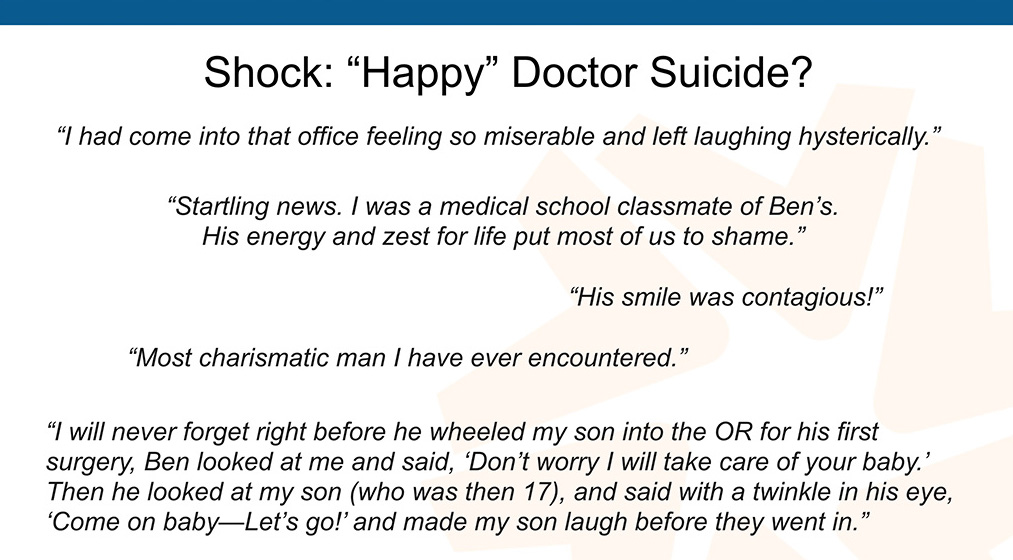

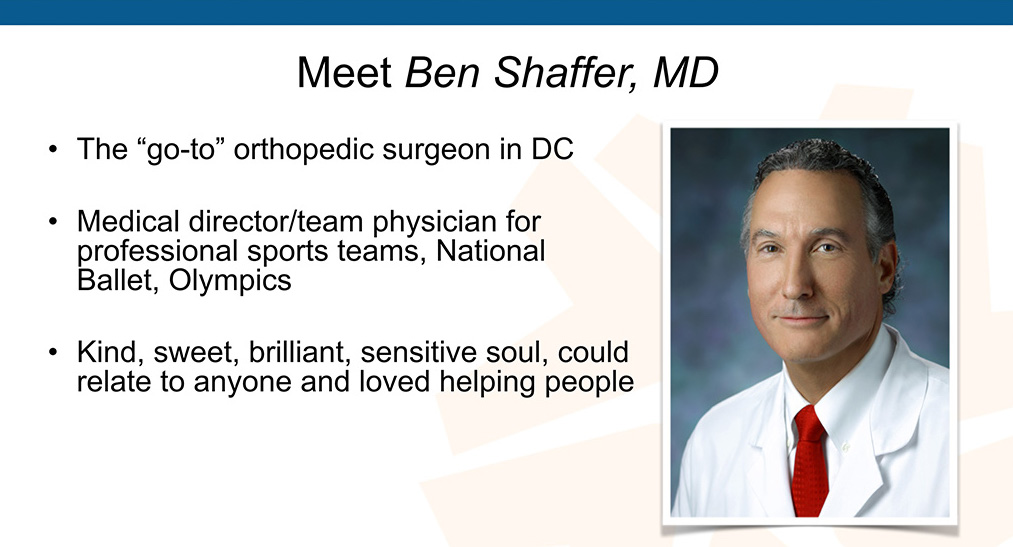

Here’s one of our brothers. This is Ben Shaffer. He was the go-to orthopedic surgeon in DC. Medical director, team physician for professional sports’ teams, the National Ballet, Olympics. I mean this is a job I would not want. How many psychiatrists in here would want to be sitting on the front row of the Olympics and when somebody has an injury of their shoulder, and that’s how they earn their millions of dollars a year, who would want to do that surgery? That seems high risk.

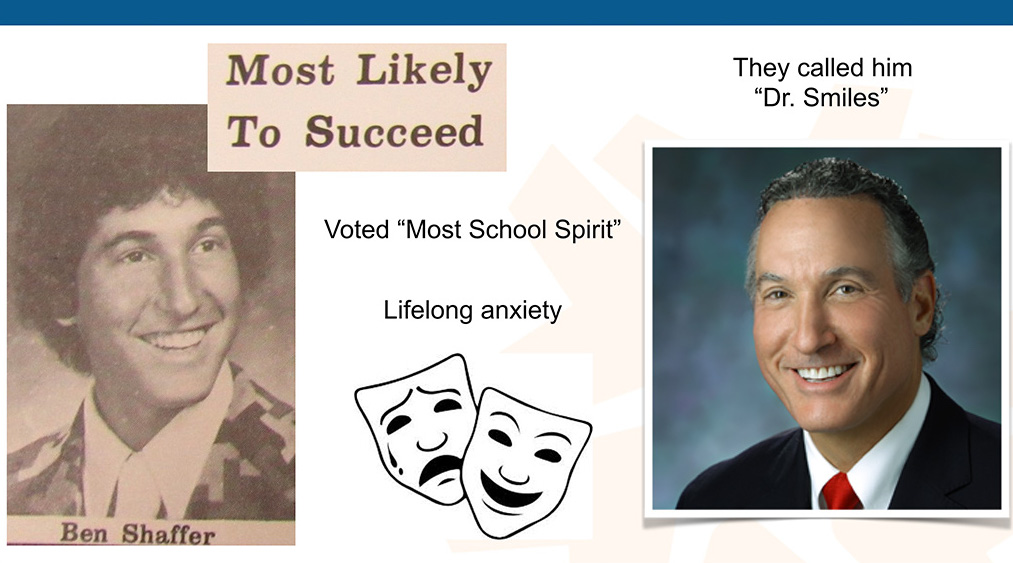

This guy is just built for this. This guy was fabulous, fabulous guy. A kind, sweet, brilliant, sensitive soul, he could relate to anyone, loved helping people, and in fact, you could look at this beautiful man, they called him “Dr. Smiles,” such a happy guy. I want to show you, this is Ben Shaffer in high school, right. He was voted most likely to succeed. Now that has a double meaning now that is terrible, right, but look at him, just look at his face. Do what my mom did with me, when I was young, stare at this man’s face, this man is a beautiful person.

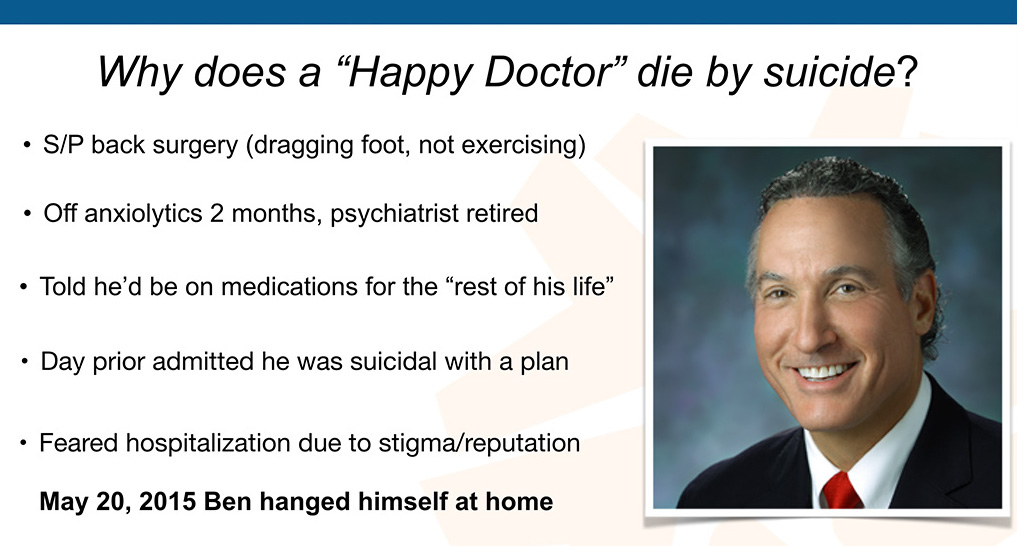

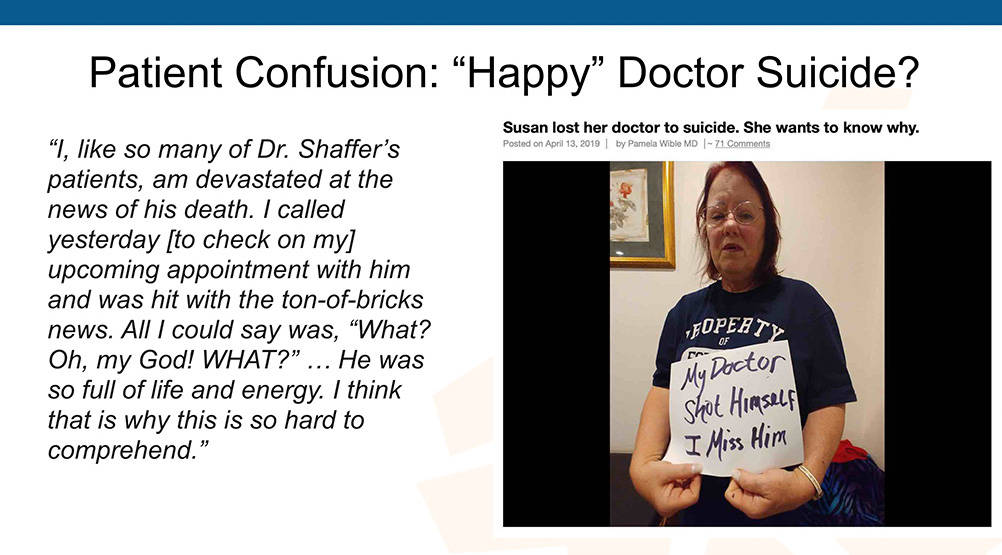

He was voted also in junior high or middle school most school spirit, had lifelong anxiety, covered up with a beautiful smile, look at that, and so here’s the situation we’re in. Now why does that happy doctor die by suicide? See this is the most confusing thing for people. Everyone, nurses, patients, they’re like, “Wait a minute, he was just joking with me yesterday. What do you mean he hung himself in his office?” “Wait, she just had a newborn baby and was so happy.” People don’t see this coming.

It’s because if what you see is the smile, you don’t see the pain, right? And so, here’s the situation, the backstory with him is that he had just had back surgery. He knew (as an orthopedist) he was going to recover from this, he was given a good prognosis, but at the time he was like dragging foot, he couldn’t exercise, which of course one of the things that helps you when you have mood issues, right? Unfortunately, he was weaned off anxiolytics two months before, and his psychiatrist just happened to retire during this whole time, so he was transferred to a new psychiatrist who told him he’d be on medications the rest of his life. Ofcourse, he’s seeing this new doc in his worst moment and the psychiatrist doesn’t really have the full picture and so the day prior to his suicide, he admitted he was suicidal with a plan, but he feared hospitalization due to the stigma and reputation.

If you’re a guy that is at the Olympics, treating all these professional sports players, you can’t risk damage to your reputation. He did not want to be committed or be hospitalized for suicide, right, and so this man made a decision to hang himself at home after dropping his son off at school. Look at what we lost here.

I mean how long does it take to become a brilliant orthopedic surgeon? I read his whole CV, it was like 74 pages, the guy has done amazing work and we lost him. This should be a never event, right? Should this be a never event?

Audience: Yeah.

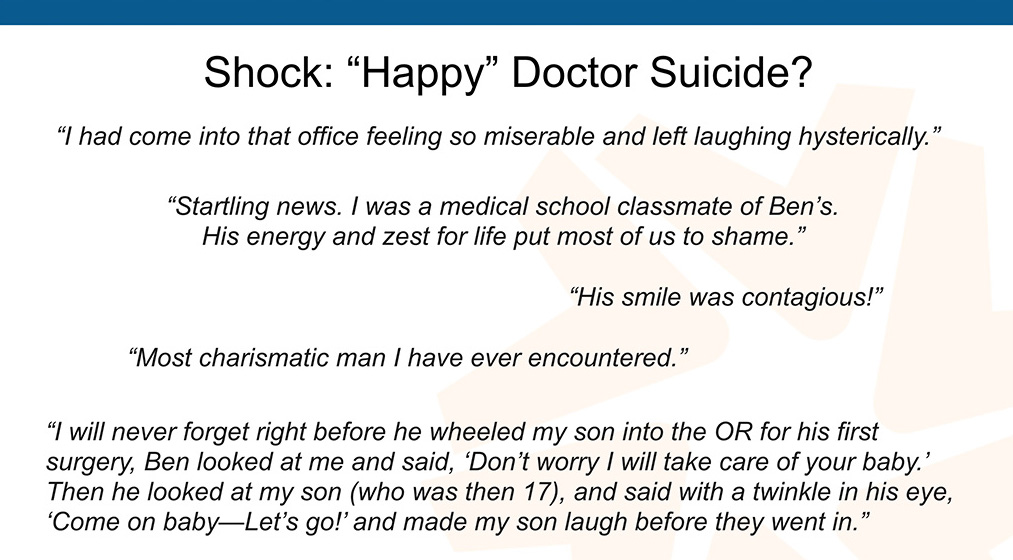

Thank you. So here’s the shock and the aftermath. These are actual quotes from people who were shocked:

What a great surgeon. What a great sense of humor. This guy made this child laugh before he went in for surgery. So patients are very confused.

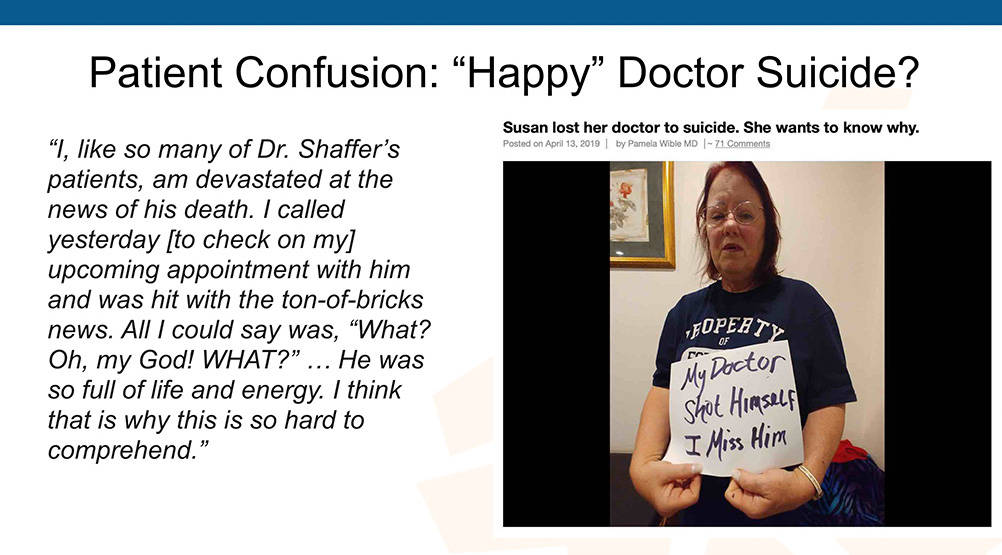

I think that’s why this is so hard to comprehend. So there’s this other group of people that we don’t think about very much who are very adversely affected by this, which are patients. Now the research shows, potentially, that maybe we lose 400 doctors a year to suicide (researchers believe that number is an underestimate). It’s probably more because we’re putting a whole bunch of these suicides in the “accidental overdose” category, which I have a huge problem with. Let me explain.

A 100% accidental overdose is a toddler on the floor in a bathroom, playing with pink pills. That’s an accidental overdose, there is no way in the world . . . you can disagree with me. . . we can talk later, I’ll stay here till midnight, I’m open minded. I personally believe there is no way that a doctor dies by 100% accidental overdose on a drug they prescribe every day to patients. This makes no sense. They totally have been to a million meetings with pharmaceutical reps. They know the narrow therapeutic index.

So it’s either a 100% intentional overdose when a doctor dies by suicide, because they line the pills up and they’ve done the calculations, right, or it’s sort of like a Russian Roulette thing, like partially intentional, “If it happens, it happens, I don’t really like my residency. I’ll see if I wake up tomorrow.” That sort of thing. I think the issue is that we probably are losing a lot more physicians to suicide than we know of, and for each of those doctors that dies by suicide, they each are responsible, at least in family medicine, the average is 2300 patients in your panel.

Now I don’t know how many patients emergency doctors see per year or in other specialties, but if you do the math, let’s just say, 2,000 to 3,000 multiplied by 400+ suicided doctors, you end up with like one million Americans (or more) every year, this just in America, who lose their doctors to suicide. We’ve abandoned one million patients, that is a public health crisis and so now I’m being contacted by patients who don’t know what happened to their doctors and they’re wanting to know,” Is my doctor on your registry?” because they love this doctor, the doctor delivered their first baby. I mean there’s a doctor in Washington State who delivered in a small town 6,000 people in that town, 6,000 babies. He died by suicide in his bathtub, because of like an insurance situation buyout of his clinic. He was the like a third-generation OB/Gyn. Apparently, he couldn’t take losing his clinic to the economic environment.

Just unbelievable. Patients are calling me, trying to get answers to what happened to their doctor because nobody tells them. If we whisper it among ourselves, these one million patients are left to wonder forever what happened to their doctor. You know what they’re told when they call for a follow-up appointment? “Pick another doctor.” Pick another doctor? This guy delivered my baby, saved my life, did my liver transplant. Just pick another one. What are we? Like just commodities? Just ridiculous.

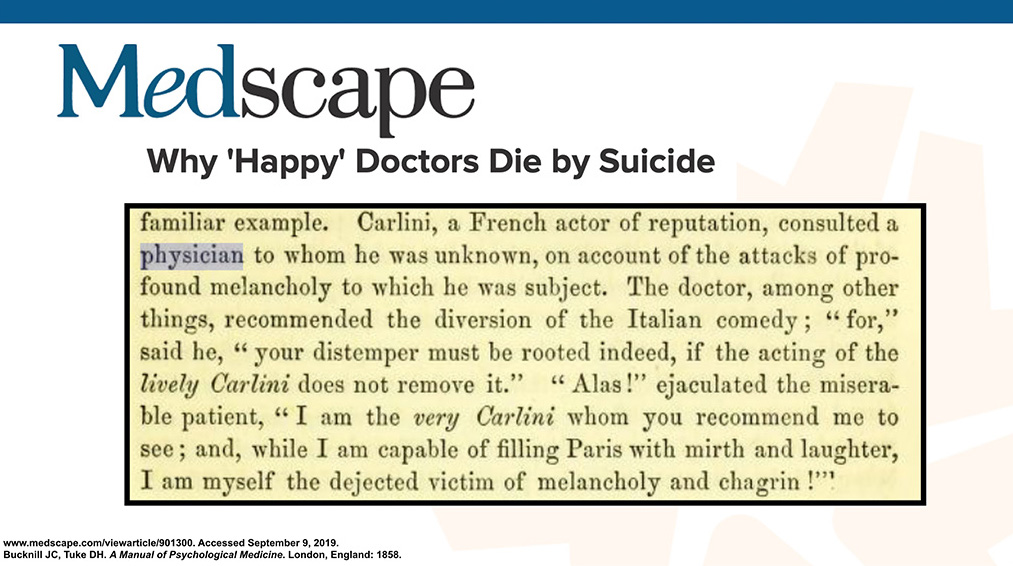

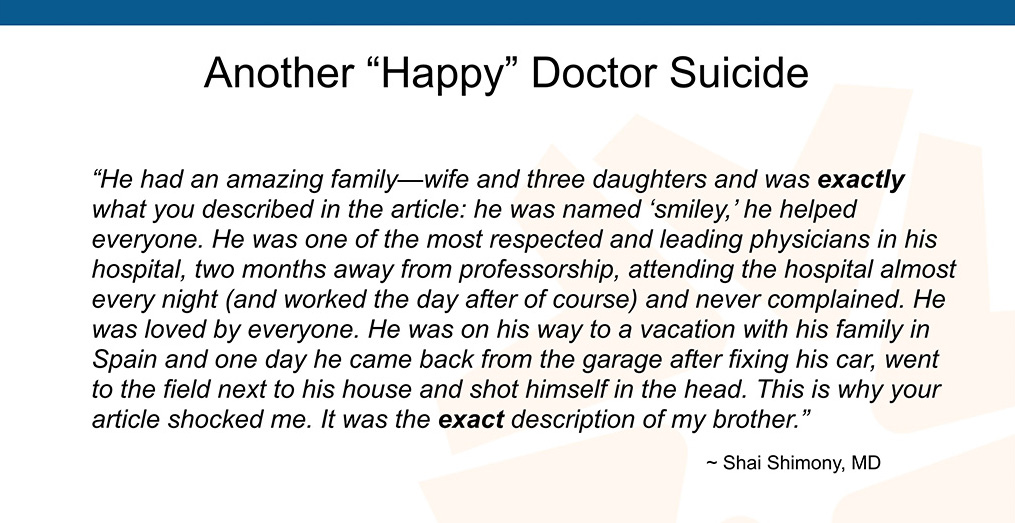

I want to tell you that I actually wrote this article, Why Happy Doctors Die by Suicide. Medscape picked it up. It became one of their top 10 articles in all of 2018. I would highly recommend you read it. I’m going to give you a little quote here, from the article, which I love, this came from a book from 1858, which apparently is where that original quote came from about doctors dying by suicide at higher rates than the general public, but this is really interesting.

Might bring back memories of Robin Williams and others who have died by suicide, looking really great on the outside. It’s a huge problem. This is the book. You have all the slides, so you’re free to grab all the original publications and look them up. This is what’s going on here in medicine. This picture, this tragedy, sort of comedy, sad/happy face like you don’t really know what’s true or not, right?

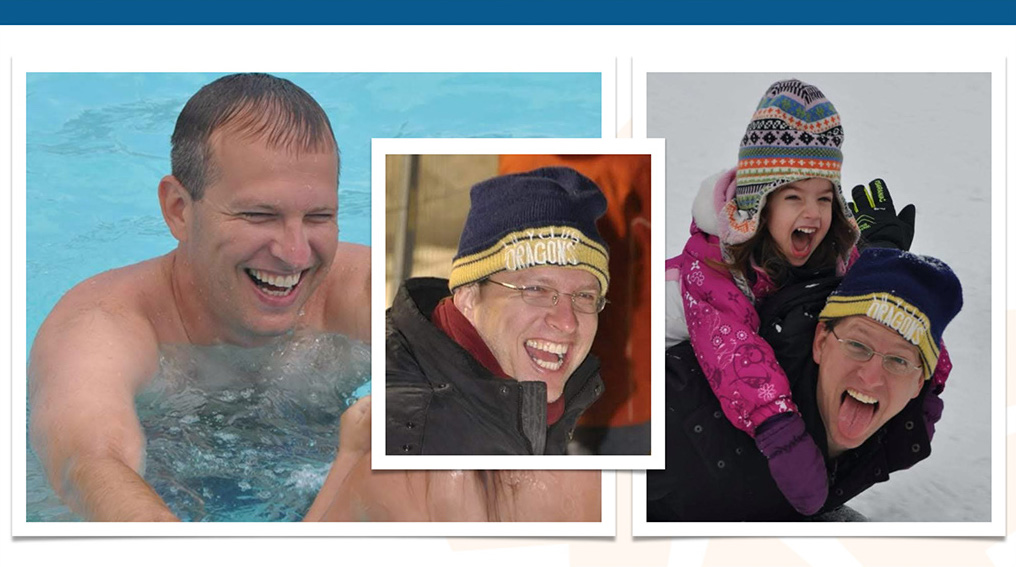

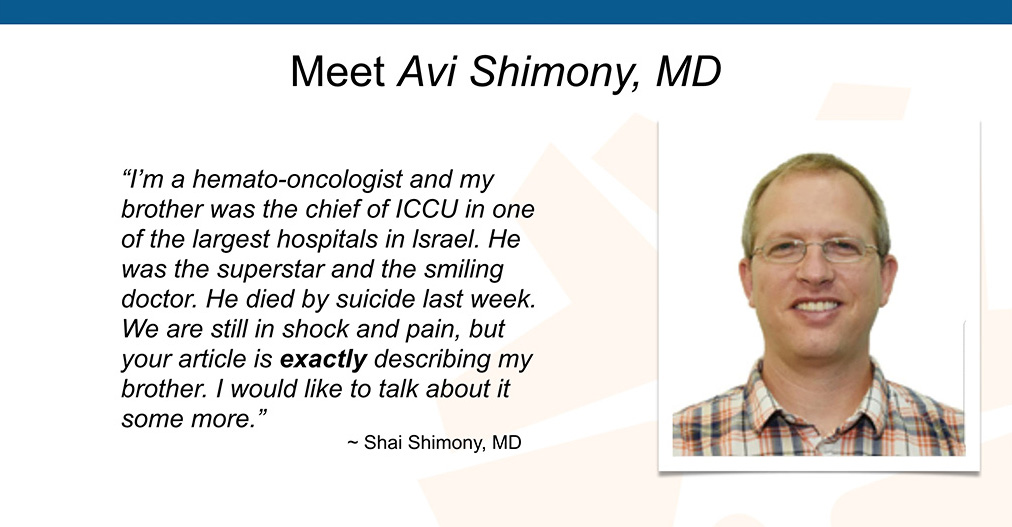

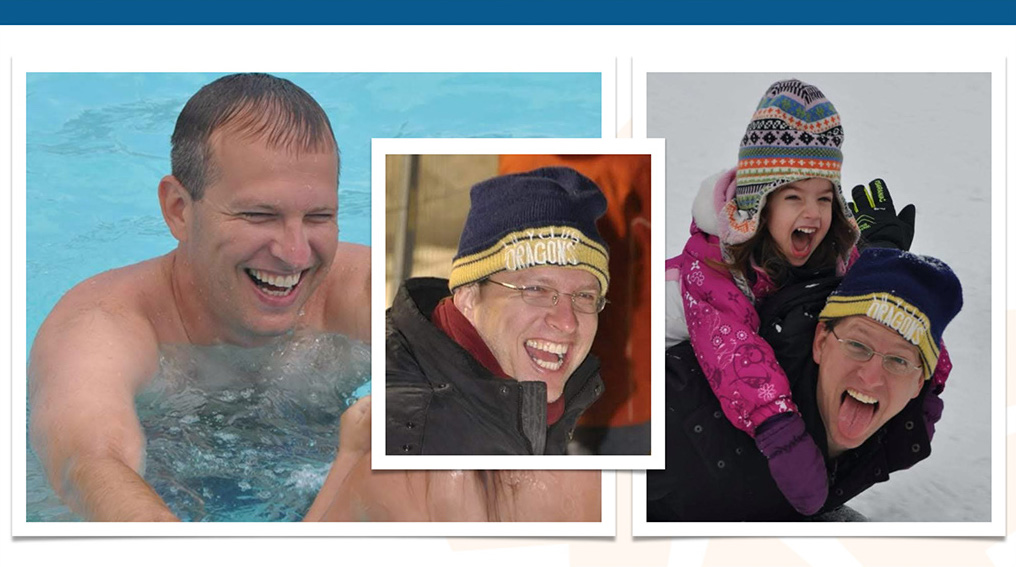

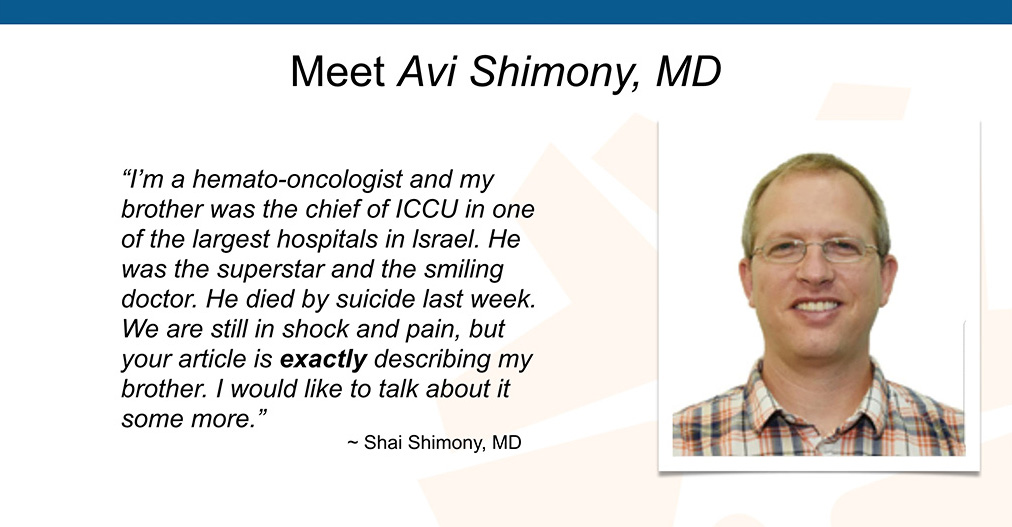

Here’s another man I’m going to introduce you to. Look at this smile. Look at this beautiful smile on this man. Look at that smile. Is that somebody who’s going to die by suicide?

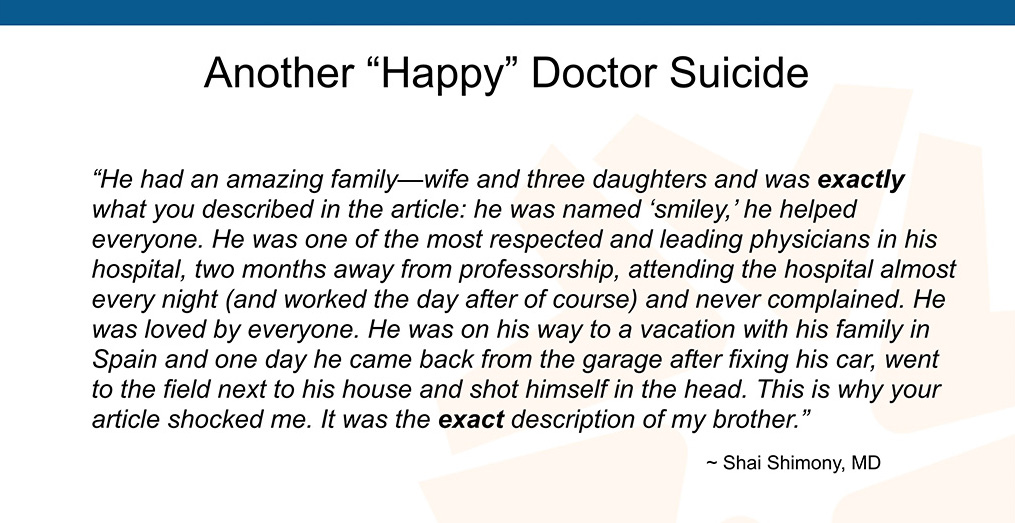

Well, he died by suicide. He died by suicide and his brother is a doctor. This is Avi at work when he’s not as happy as sliding in the snow with his child, right?

I ended up on Skype with Shai Shimony and another brother. In fact, I didn’t realize this, they had found my “happy” doctor article and read portions of it at Avi’s funeral in Israel. He went on to explain this in an email. Notice how many times he uses the word exactly.

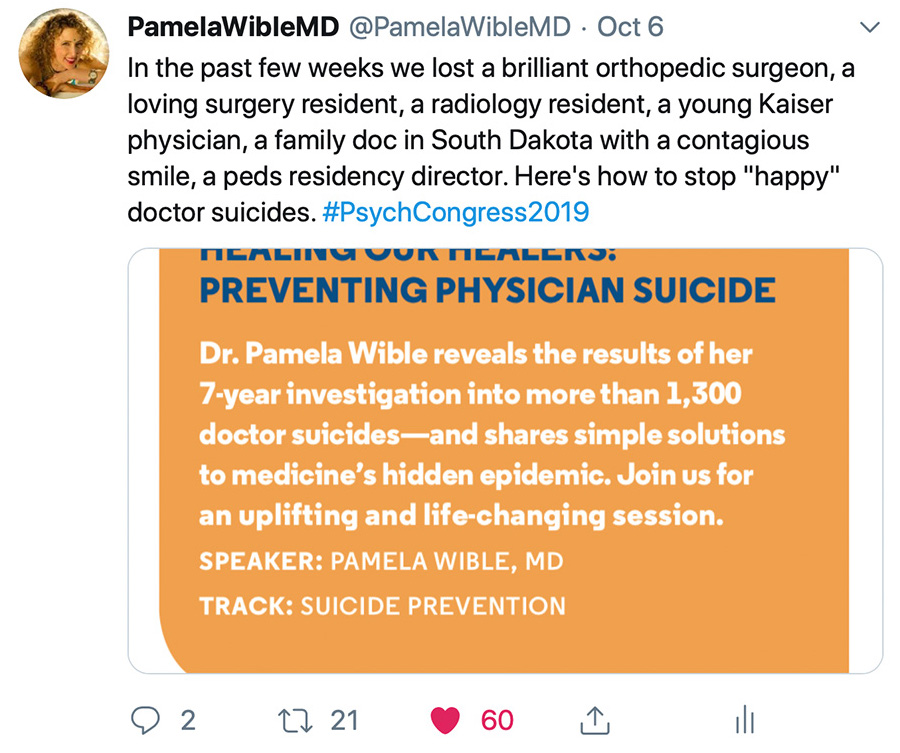

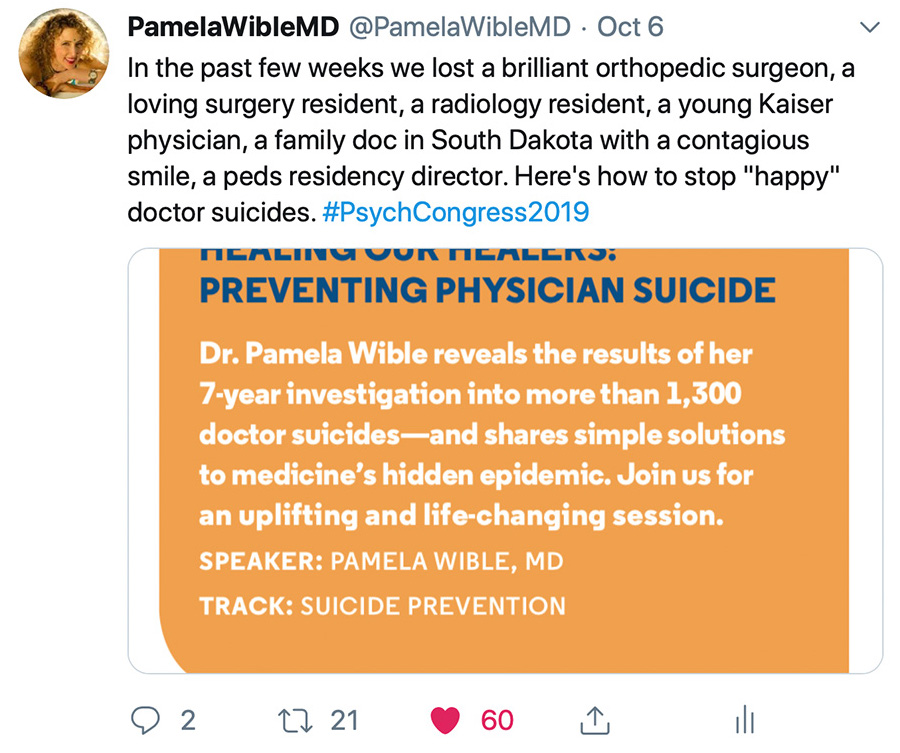

How many other doctors are the exact description of this? So many. If you go on Facebook, you can see beautiful pictures of smiley faces of doctors who’ve just died in the last few weeks. I was going to share this at the appropriate moment here. I just posted this on Twitter a few hours ago:

Okay, so I think the issue is that everyone is just in complete shock and they always in the aftermath want to know, “Wait, he was happy. What could we have done? Could we have done something? How could we have intervened?” But it’s very hard to intervene when all you see is smiley faces.

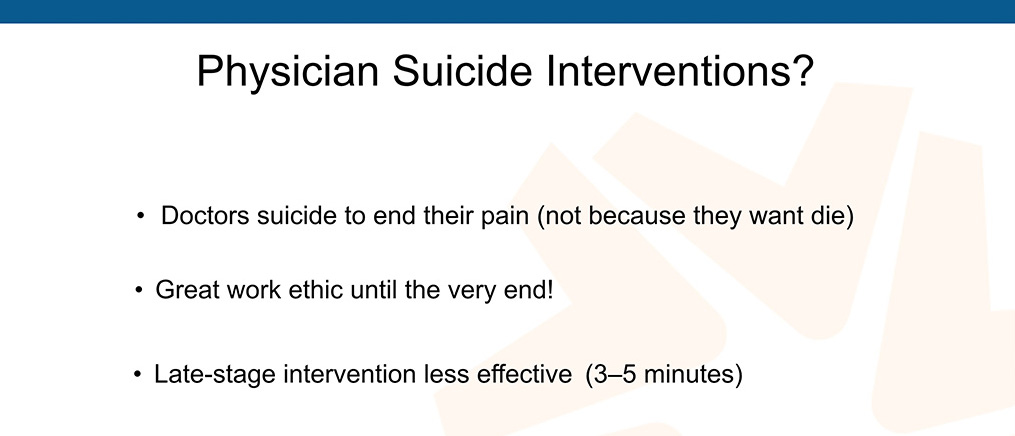

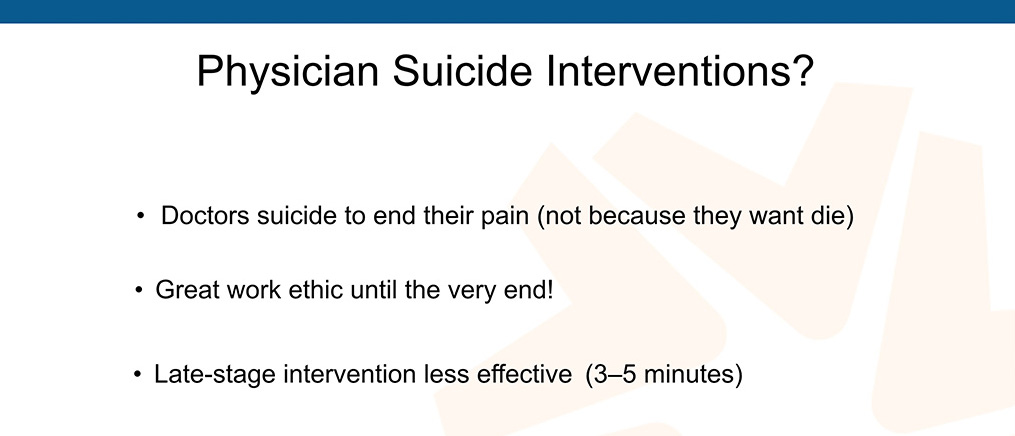

I interviewed a number of male physicians who survived their suicide attempts and I asked them, “Hey, how long between when you sort of made the decision, ‘That’s it I’m going to die by suicide’ and you actually sort of grabbed the gun, got the pills, started moving?”

Three to five minutes.

Now if we wait till the last three to five minutes, it’s going to take a lot of heroic psychiatrists and such to jump in there and find these people, but meanwhile, these people have had hundreds of missed opportunities, over decades. We’re surrounded by the highest density of health professionals who could help us and yet, we’re sort of not doing anything, that’s working very well or this wouldn’t be a problem, so I am really encouraging you to take action and the action steps are very simple and I’ll talk about that in a minute.

I want to show you a picture of a wall in my home business office that’s covered with the photos of doctors who have died by suicide, and medical students. I really don’t want to add anyone else to this wall. I don’t have enough space. I’m in a 900-square-foot house, I have a very like voluntary simplicity lifestyle. I don’t have enough wall space for this and so we’ve got to really do something about this.

My partner who’s very funny, he’s like, “You know, when you go to these conferences, these doctors’ spirits are still here. I can feel them here. They live in the house, as soon as they die, they move in. This is really not great for our relationship.” I don’t know, I mean, just to salvage my relationship, this guy’s a musician. He says, “I never thought about suicide before I got together with you. Now all we talk about is doctor suicide. Yeah, this is killing our sex life, this is not going to work out. I love you, but we have all these dead doctors, all I think about is dead doctors. This is not inspiring. I don’t feel like making music.” It’s causing slight rift. He’s a sweet guy. He’s like living with the house cat, he’s very sweet but the doctor suicide thing, I mean, I need more people to help.

Okay, full disclosure again, I in 2004 was a suicidal physician myself. I’m not a violent person, so my method. . . I guess I was just deeply depressed, it was 100% occupationally induced. I ended up sort of in bed after quitting my last job, six jobs in 10 years looking for a way to practice real family medicine. You know, the housecalls. It’s impossible to get to know people, like seven minutes in a cubicle, that’s all they wanted me to do. Seven minutes. Just wanted me to generate the most revenue per millisecond. I mean it caused this terrible existential crisis, because I feel like I was born to be a healer. I saw what real doctors did in the 1970s and they weren’t in cubicles and they weren’t doing seven minute office visits so I was just like, “What is this?”

The occupational distress. It caused me to fall into a deep depression and I was praying every night that I could die in my sleep. I was trying to will it to happen. The problem is when you’re 36 and you’re a vegetarian and you’re really healthy, it’s so unlikely to die in your sleep. So I’m still here. I mean, I’m still here and what happened after that, I mean, so I had an epiphany to start an ideal clinic. I was like, “Okay, if I’m not happy and my patients are not happy we’ve got to do something different.”

Suddenly it clicked in me, like maybe I could just ask them to help me start the clinic because I’m exhausted. When you’re depressed, you’re not super-creative about, “how am I going to get out of this.” Right? But I live in a beautiful small Eugene town and my patients love me and I love them and I was just like, I hosted a town hall meeting where I said, “Look, I’m suicidal and depressed. I can’t figure out what to do. I don’t like seven-minute visits. You don’t either. Tell me what you want, I’ll do it, as long it’s basically legal, I’ll just do it.”

They wrote me one hundred pages of written testimony. I just followed what they said and I’ve been happy ever since—for 14 years.

My mom thinks I’m hypomanic. She thinks I use excessive happiness as a coping strategy. I’m totally open now and I’m in a room with all these psychiatrists. If you can DSM me properly, you’ll save a lot of other people the hassle, because I don’t know what’s wrong with me. Am I hypomanic? Am I too happy for no reason? I don’t know, but I believe mental illness appears on a continuum. We all have had experiences with mental health issues. I believe in channeling your mental illness into something productive, like saving suicidal doctors or if you’re manic, go into marketing.

Match up your mental illness with the right profession and give people an outlet. I’m just channeling my (whatever it is) excessive happiness, grandiosity, histrionic I’ve been called, but you know what? I come from a family of physicians and entertainers. I’m related to the Three Stooges. Okay, so it’s like, “Am I being too theatrical?” I don’t know. Hey at family meals when I was younger, I’d sit at the table and my family and it was so funny, I would fall off my chair laughing all the time, because my dad is hilarious. I’m related to all these theatrical people but suddenly when psychiatrists look at me, they’re like, “You’re histrionic.” But I’m an extrovert. I understand most physicians are introverts and yes, sometimes I wear glitter and they’re like, “Hmmmm . . . grandiosity.” I did a talk in a medical school and I had all these folks lined up with question. I asked this woman, “So what’s your question?” She says, “I’m just here to see if you’re really wearing glitter.” I said, “Yeah, you can wear glitter—and be a doctor. You can be a doctor—and be a human.” It’s possible, I’m proof.

One day I was at my mom’s house. We both went to the same medical school. I’m sitting there. I’m looking through our alum magazine. For some reason, she gets the alumni journal and I don’t usually. I haven’t received any alum stuff from my med school. I’m still paying for therapy to recover from medical school. I don’t have any money to donate. Some suicidal docs have disclosed, “And by the way, what really pisses me off and I just got this thing in the mail, they want me to donate money to my medical school. They gave me all these psychiatric problems. Why do I have to donate money to medical school?”

Anyway, I’m looking through this alum magazine, you know at the end, they have updates on what your classmates are doing and you sort of want to voyeuristically figure out all the awards everyone won that you didn’t and you want to look through there, and it’s like, “Oh, my God.” I look through under obituaries, I saw the name my anatomy partner who I dated. You know how startling that is because he was like 39 and I tried to call his office to see what happened. I tried to track down his family. Then at a certain point I was like, well, let me back up. Leave it to the family, it’s none of my business. I love this guy. I dated him. We did some really interesting things after hours in the anatomy lab, and so it’s like I just wonder what happened to him. Then this other man I dated in medical school for three years, he died suddenly in his sleep. Right, I feel like, “Wait a minute, both men that I dated in medical school are dead, so what is going on here?”

Let me chronologically catch you up. I open the clinic happily ever after in 2005 on April Fools’ Day and then 2012, I ended up in the second row of a memorial service for the third doctor that we had lost to suicide in my small town in Eugene, Oregon, within a year. Top guys, like top of their game and I was sitting there and as a truthspeaker, you have to know, it was very odd, everyone knew that he had died by suicide, by shooting himself in the head in a public park in the middle of the day. People were all whispering why, nobody said suicide out loud during the whole service. Everyone was whispering in the bathrooms and the corners.

I was like, “What kind of behavior is this for adults?” Why are we not talking about this? Everyone was asking in whispers, “Why did he shoot himself in the head?” That’s what they wanted to know and it’s like, we’re not going to get very far if nobody will say this out loud, and so I’m sitting there in the second row and I kept hearing this why (I guess I’m an empath). I really pick up on what’s going on in a room, right, so I just kept hearing “Why, why, why, why” and I just felt this, like a reverberation in my head, “Why, why, why, why,” and so I just started counting on my fingers how many doctors I knew personally had who had died by suicide.

Ten. I knew 10 doctors who died by suicide. I was only 41. That’s a lot of people to know in your profession that have died by suicide so I appointed myself an investigator. I wanted to know why my friends were dying by suicide. I had no idea this would lead to me helping my entire profession figure out what to do next. This was a personal quest of mine, because I had lost all these people. Please help me. Please help me. Please help me stop these deaths.

I wasn’t very smart about figuring out why at the beginning. I came up with a list of 35 reasons on the fly that I thought might have been causing doctor suicide in 2012. I published a blog. What was funny is that I had a blog for a year and nobody was coming to my blog. No comments, no likes, no shares. Nothing. As soon I wrote Why Doctors Die by Suicide, it was like 80 comments (now 234) and a million emails and I was like, “Well, this is reinforcing that I probably need to keep doing this.”

Five years later, fast forward, I end up writing a piece, basically what I’ve learned from the first 757 doctor suicides, that was picked up by The Washington Post and then generated, of course, a lot more interest. Media begets media. I was very frustrated at the beginning, because I kept talking about all these older male doctors who had died by suicide and nobody seemed interested.

I couldn’t get the media interested. I told my therapist, “This is so frustrating. Like nobody cares that all these people are dying,” and she tapped me on the shoulder because I’d figured out some solutions and she’s like, “Well, you know, you can’t really solve a problem, that nobody knows exists.” Oh, no. I’ve got to go back to preschool. You know, I’ve got to go back and do a lot of the whole public awareness, decrease professional denial campaign. Frustrating!

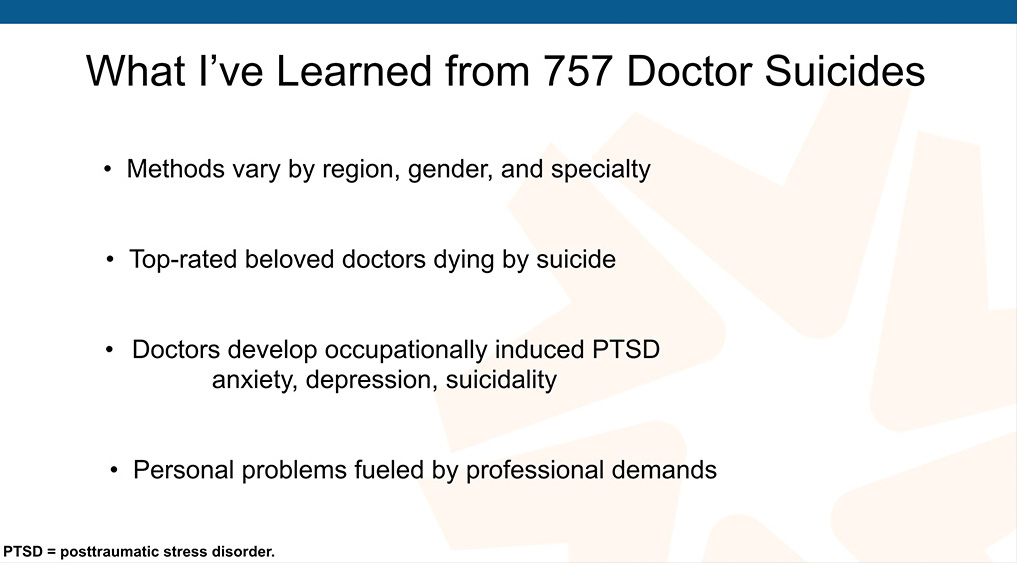

Oh, so anyway, what I’m saying is I’m extremely happy that the media has picked this up, that there’s now been a film (view movie trailer here). We’re finally getting the media traction that we’ve needed all along, Now medical conferences like this, forward thinking conferences are really taking this on and so here are some of the things I learned from the first 757 doctor suicides. We’ve known about the high rate since 1858.

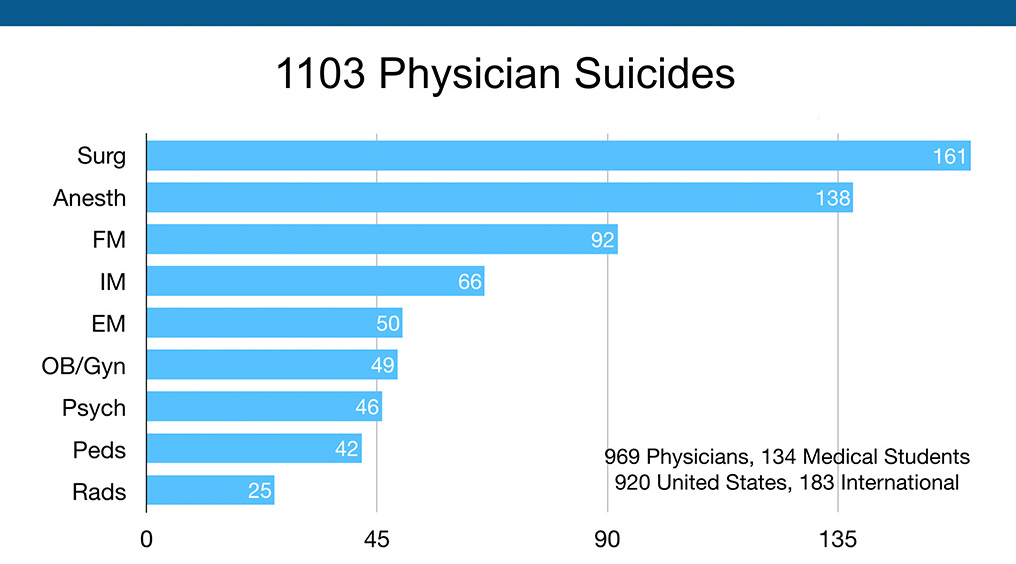

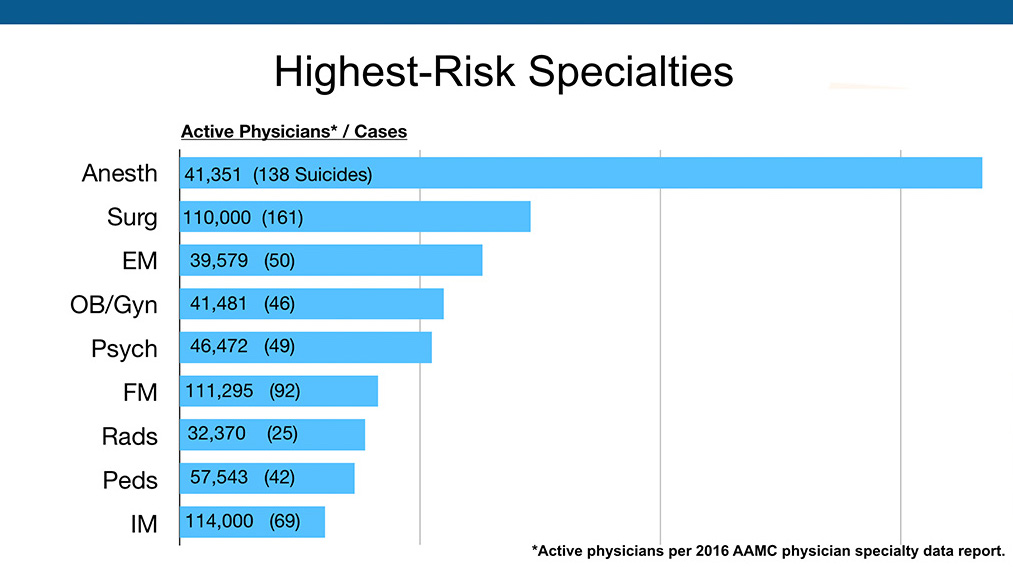

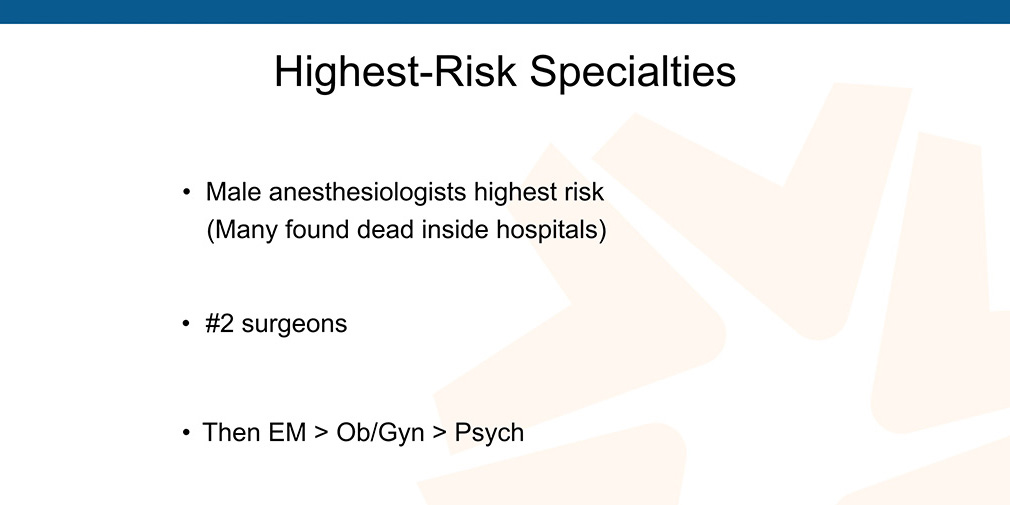

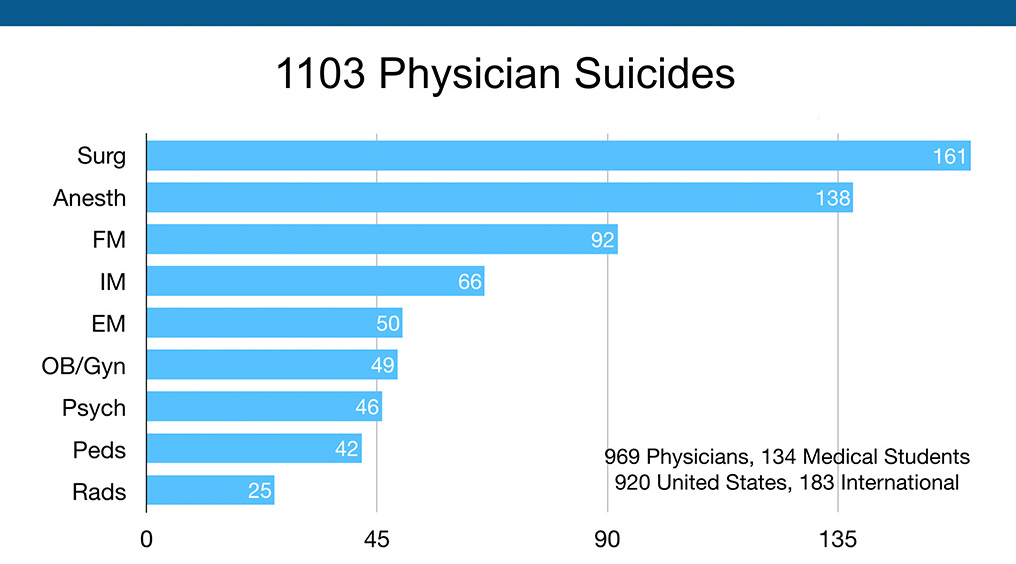

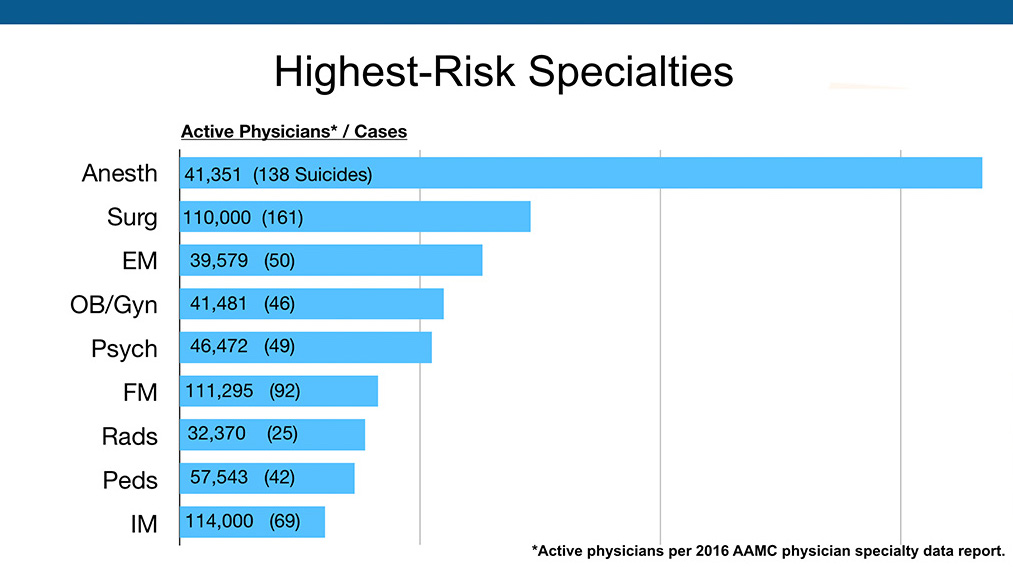

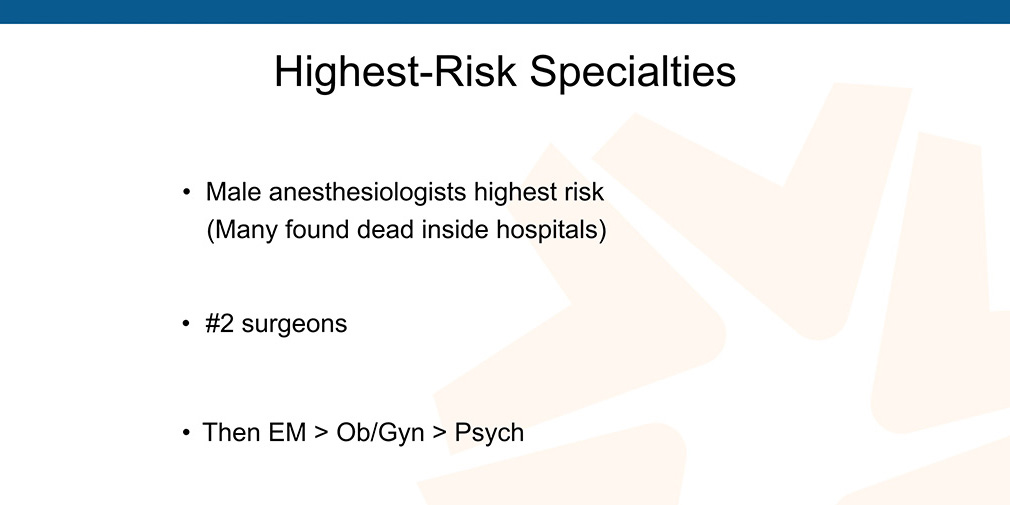

Physician suicide is a public health crisis because of just the sheer volume of people who are dying, of a dying family member, loss survivors that are suffering and patients that have been abandoned, like I said earlier and most doctors, many doctors, actually have lost several colleagues to suicide and I sort of had this hunch that, yes, anesthesiologists were number one and number one in a contest you don’t want to win, as the highest risk for specialty because I would get emails from anesthesiologists listing eight colleagues they’d lost to suicide.

I’ve never received any emails from any docs in other specialties with that many losses. You’ll see a graph in a little bit where I actually have numbers by specialty. I thought psychiatrists were highest risk, I mean just from looking at my mom going, “Oh, no, oh, no,” but actually psychiatrists are the highest risk non-surgical specialty.

The methods vary by region, gender, and specialty, of course, you’re using whatever you have, you’re stepping off tall buildings in New York, on the West Coast of the US, using guns. In India, they’re hanging by saris, ceiling fans. They just, you know, three to five minutes, they’re going to pick whatever they have.

Some have been critical because reveal these methods of suicide. “You’re not supposed to talk about this. You’re not supposed to talk about the method. You’re supposed to follow suicide reporting guidelines.” Like how are we going to discuss this as medical professionals if we don’t piece this apart and get the data and the method is so important.

If you Google “doctor found dead in hospital” those are all male anesthesiologists. They all overdosed in closets and ORs and one even happened in our town. A high-ranking official’s husband in my town was dead in the hospital for several days before they found him in a closet of an overdose, an anesthesiologist. This is shocking. Shocking. I mean just shocking that you could be dead in a hospital for that long before somebody noticed.

Top-rated beloved doctors are dying by suicide. Doctors develop occupationally induced PTSD, anxiety, depression, suicidality. The personal problems, some people will blame, like, “Oh, he was in the middle of a divorce.” Well, what caused the divorce? Working a hundred hour weeks as an orthopedic surgeon, hasn’t seen his wife in weeks. Like haven’t had sex in so long, and he’s just throwing money at her to like sedate her because he’s away at the hospital.

Let’s stop blaming personal problems, saying, “He was upset.” Leadership within institutions will defame and blame the deceased: “Oh, she was sad.” Well, why was she sad? Because her human rights are violated, because she’s working a hundred hours weeks, because she’s been bullied. You know, there’s a reason doctors are so desperate and hopeless and my impression here tracks back to professional etiology, including the fact that you’ve not been able to get mental health care without stigma. So many docs feel like they are dying inside because of our profession. The last straw there was your recent divorce or your disabled child or something terrible, your house burned down, whatever.

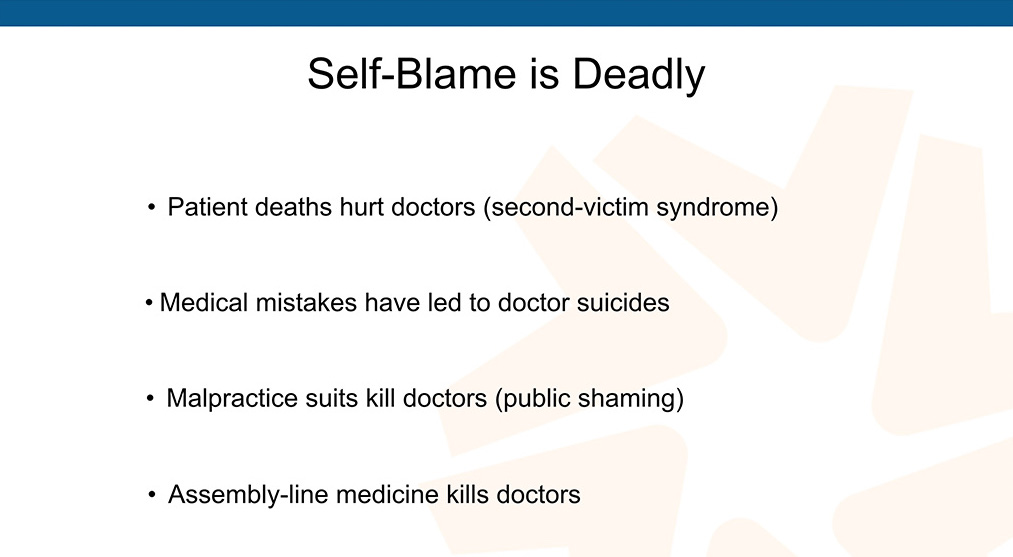

If you track back and do a little archaeologic dig, psychological autopsy, you might find that the originating issue is probably professional somewhere along the way. Another huge issue is self-blame. It’s deadly, it hurts doctors. Second Victim Syndrome has been studied by Dr. Stacia Dearmin, if you’re not familiar with her, she’s a physician who has done a lot of work on this, helping other physicians with Second Victim Syndrome.

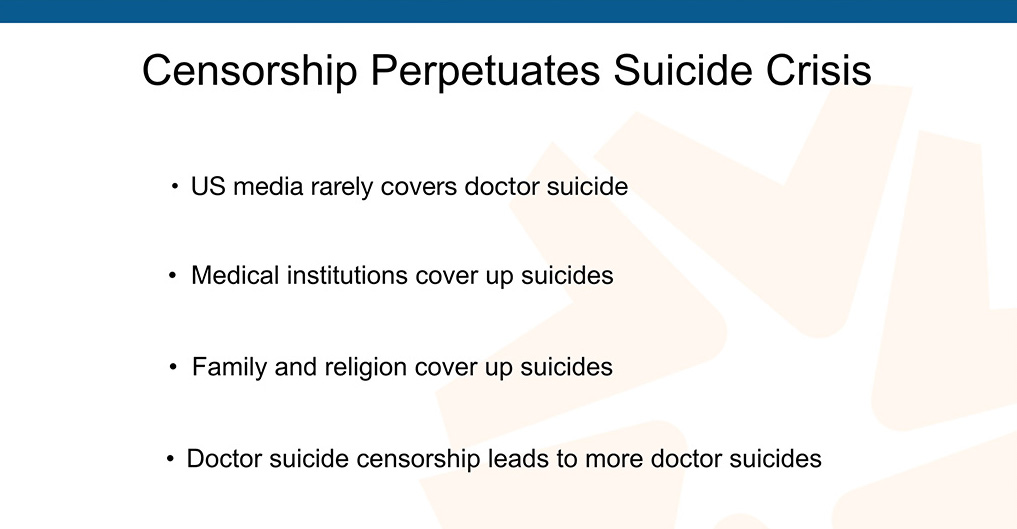

Medical mistakes have also ed to doctor suicide, even if it’s like it’s not your fault. Even if you did nothing wrong, somehow doctors still have the self-blame thing. “Well, what if, what if I checked the labs? What if I would have changed the medicine?” And then they can’t stand it, they still, they take their own lives. Assembly-line medicine kills doctors like it almost sort of killed me—and censorship is part of the problem. The US media rarely covers doctor suicide, medical institutions cover up suicides, family and religion cover up suicides and the censorship just leads to more suicides.

If we did not talk about high blood pressure, diabetes or schizophrenia, where would we be? Nowhere.

This is a graph I put together of the first 1103 physician suicides with a breakdown of the raw numbers that came to me after the first 1103.

This graph above is not as important as the next one below where I used the 2016 AAMC Physician Specialty Data Report to rank specialties based on the numbers of physicians per specialty. When you break it down based on the numbers per specialty, anesthesia is through the roof.

Anesthesiologists die by suicide at 2.3 times the rate of surgeons and 5.5 times the rate of general internal medicine. According to my data, the first 1103, we need more data. I’m not saying this is written in stone. This is just what I got and it gives us a place to start the additional data gathering. Male anesthesiologists are the highest-risk group. I currently believe the highest risk for suicide are anesthesiologists and veterinarians. Psychiatrists are the highest out of non-surgical specialties for suicide, according to my data.

By the way, doctors end their lives not because they really want to die, they just want to stop the pain and they can’t figure out any other way and they certainly have a lot of access, especially anesthesiologists. What’s surprising that’s sort of not surprising when you think about it is they have a great work ethic until the very end.

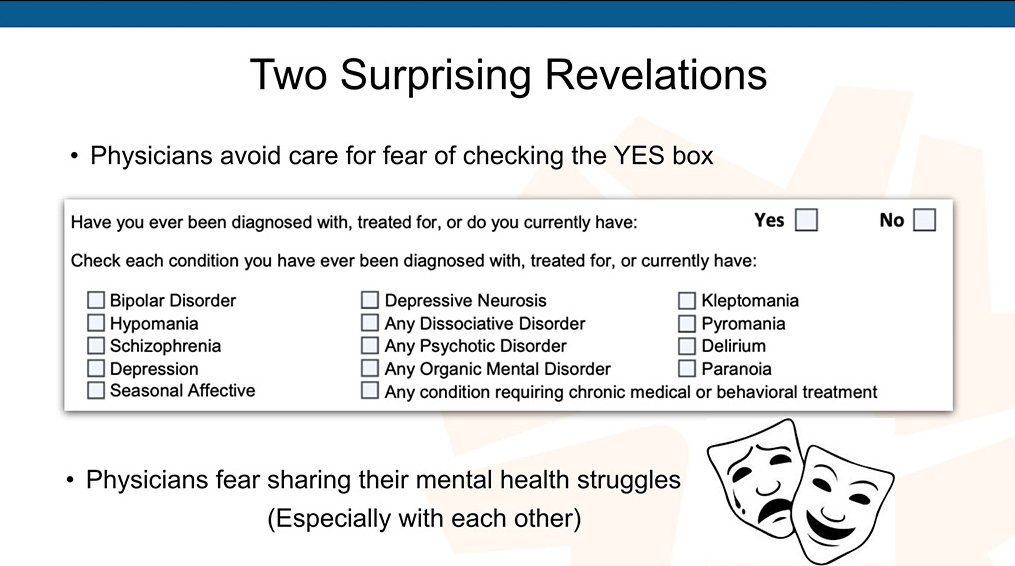

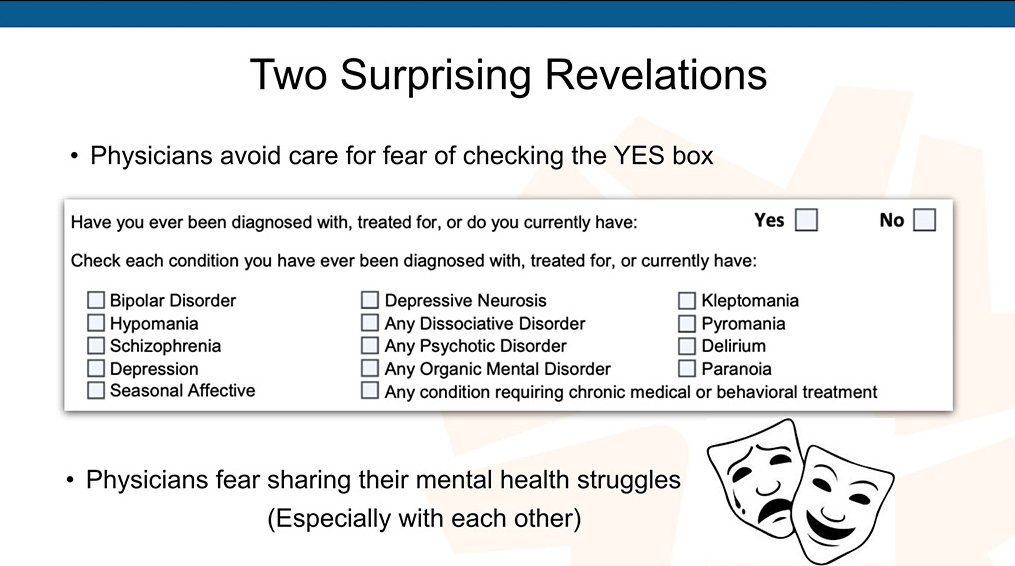

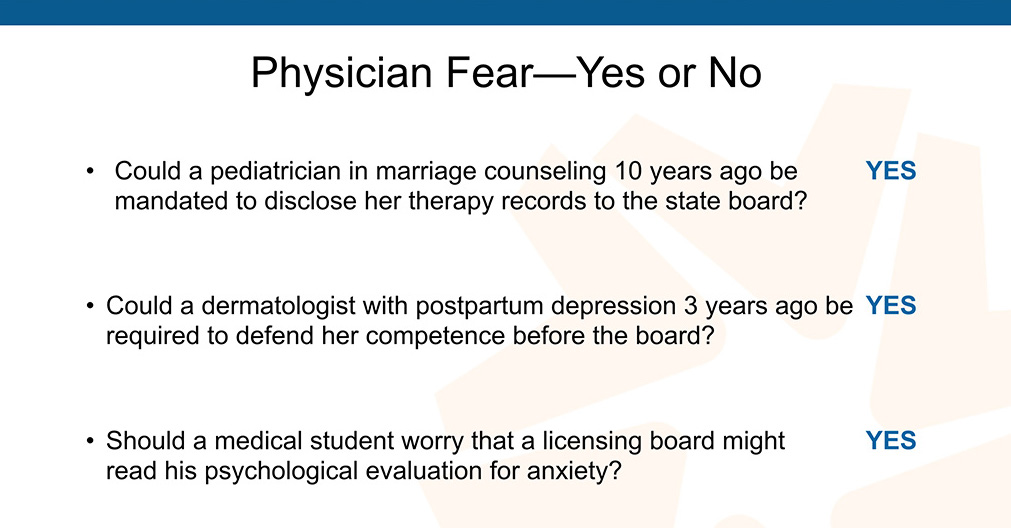

They’re smiling and doing complex surgeries and cracking jokes, thumbs up to the surgical team, and then they shoot themselves up in the closet. Like I said late-stage intervention is less effective, you only have three to five minutes, but here are their surprising revelations. Now we’re going to go into solutions and deeper dive. Fact is physicians avoid care for fear of checking the yes box. This is an actual medical licensing initial application for the State of Alaska, a section of it:

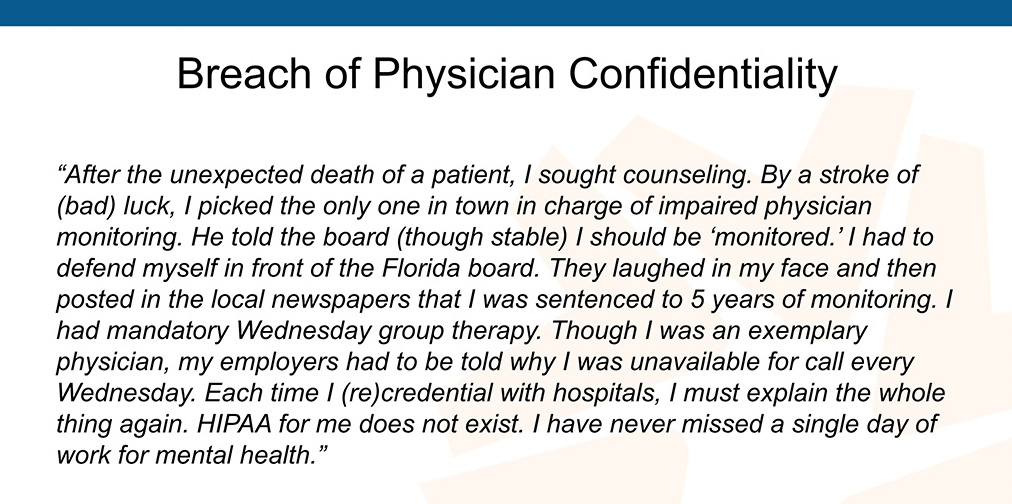

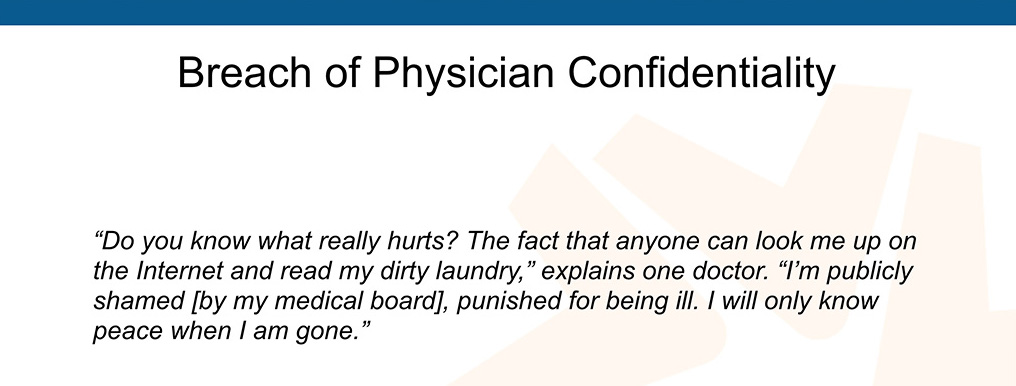

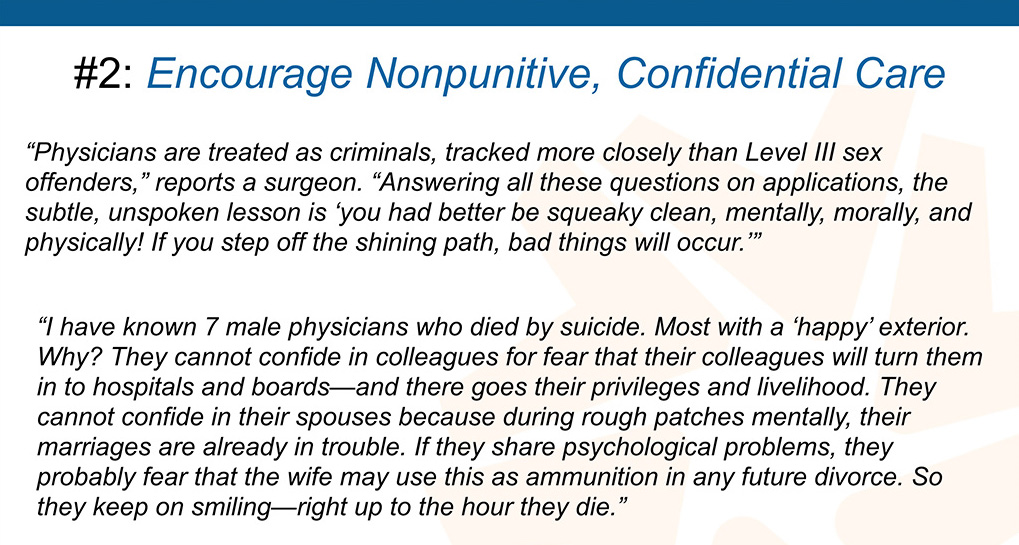

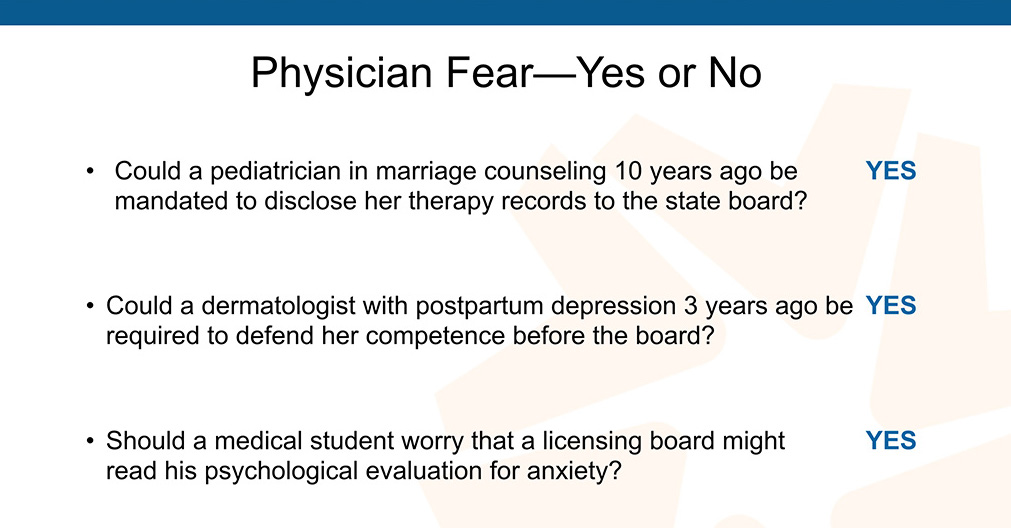

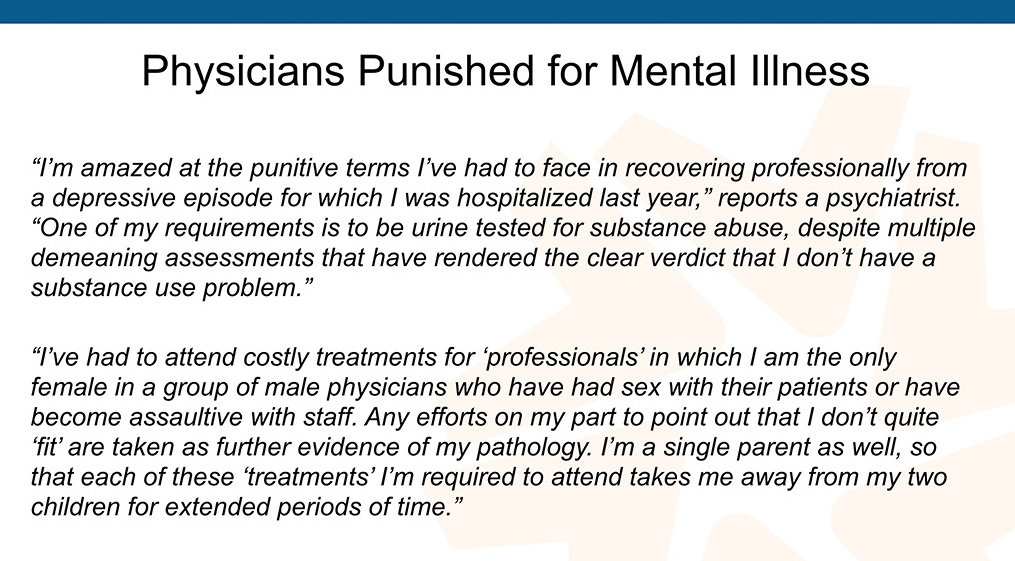

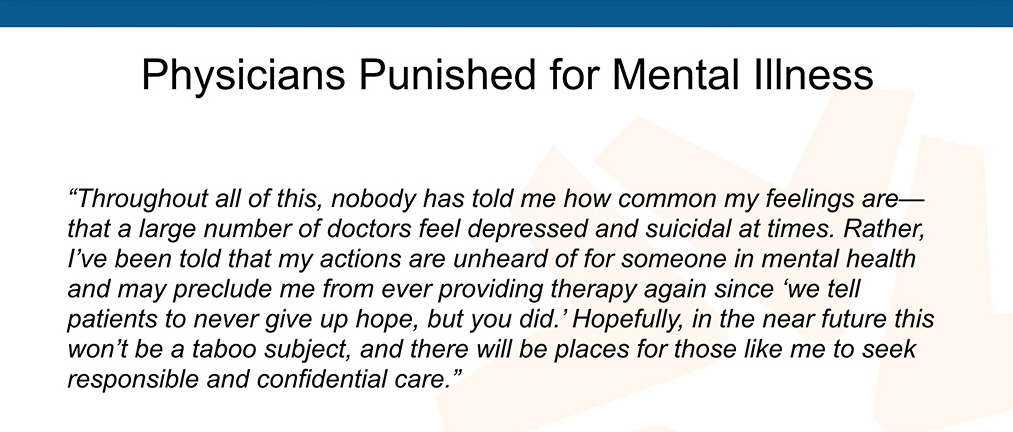

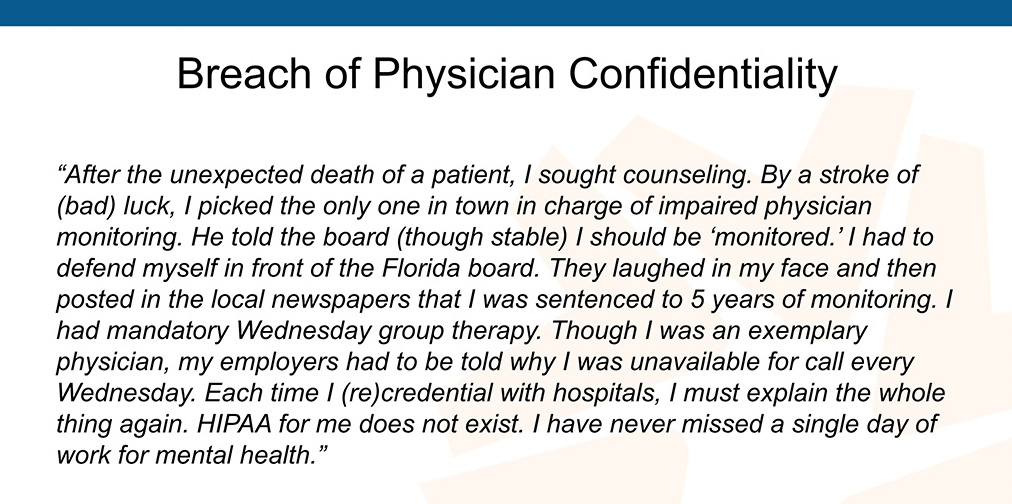

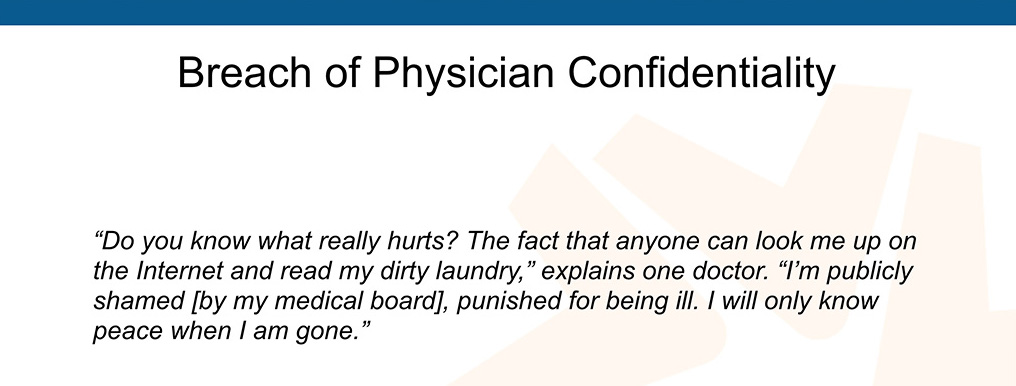

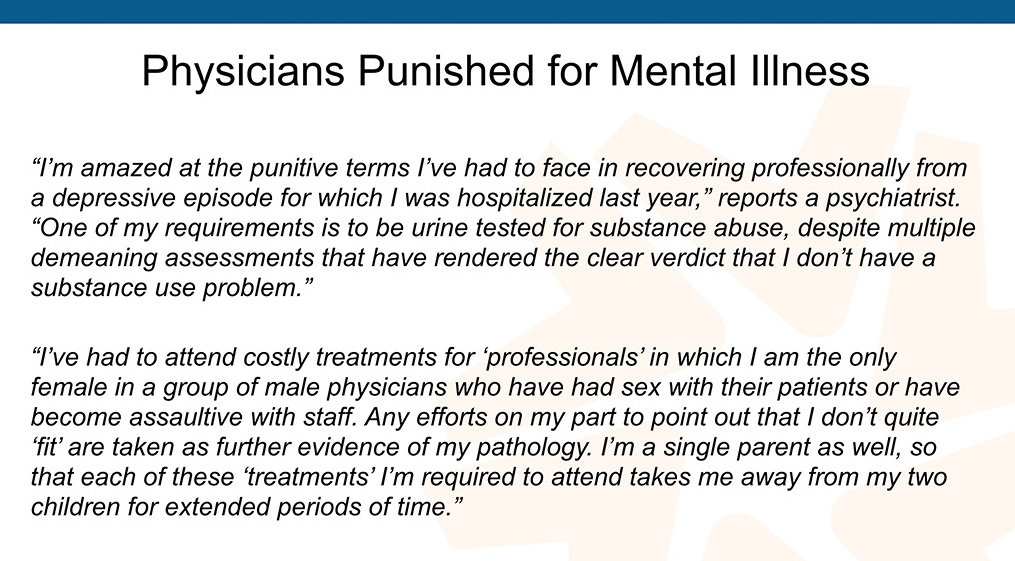

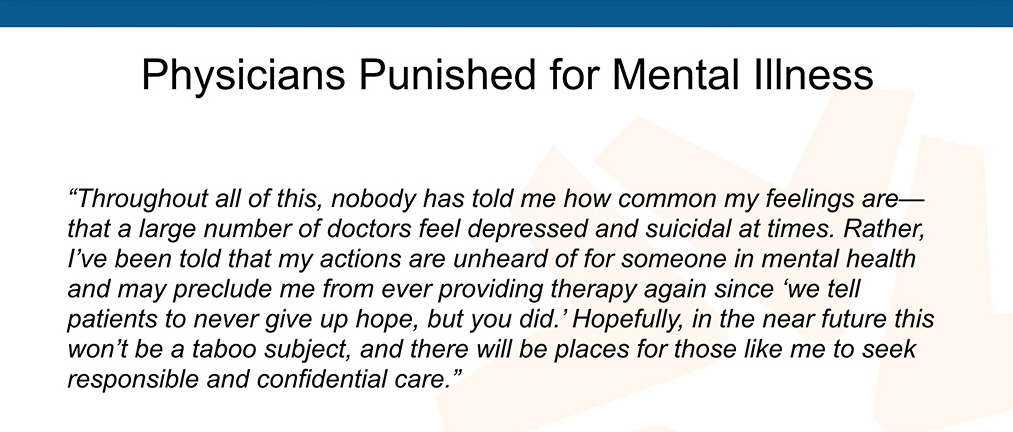

Pretty invasive and a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act. As a result, physicians fear sharing our mental health struggles with the medical board. They’re adversarial. Medical boards exist to protect the public from us, so they’re fishing for reasons why they should keep you away from patients. So physicians fear sharing their mental health struggles with medical boards and with each other because there’s like this subtle sort of suggestion that we should turn each other in.

See a doctor suffering, drinking a few extra drinks at a wedding, turn him in, turn him in. Turn all these guys in, we’ll take care of them. We’ll beat the shit out of them and . . . (Sorry) . . . so this is a problem. This is like, if you’re looking for the archaeologic dig, where do we start with this, this is the number one thing. We’ve got to get rid of these questions. They’re illegal and they are creating a huge hazard. They’re creating this mask scenario where we’re not safe to cry.

A female resident called me one day because she was crying after the death of a patient and she got in trouble, written up at work as unprofessional. She called me because she wanted to know if I had any scientific research proving that it’s okay to cry. You’ve got to be kidding. Is this where we are with our profession?

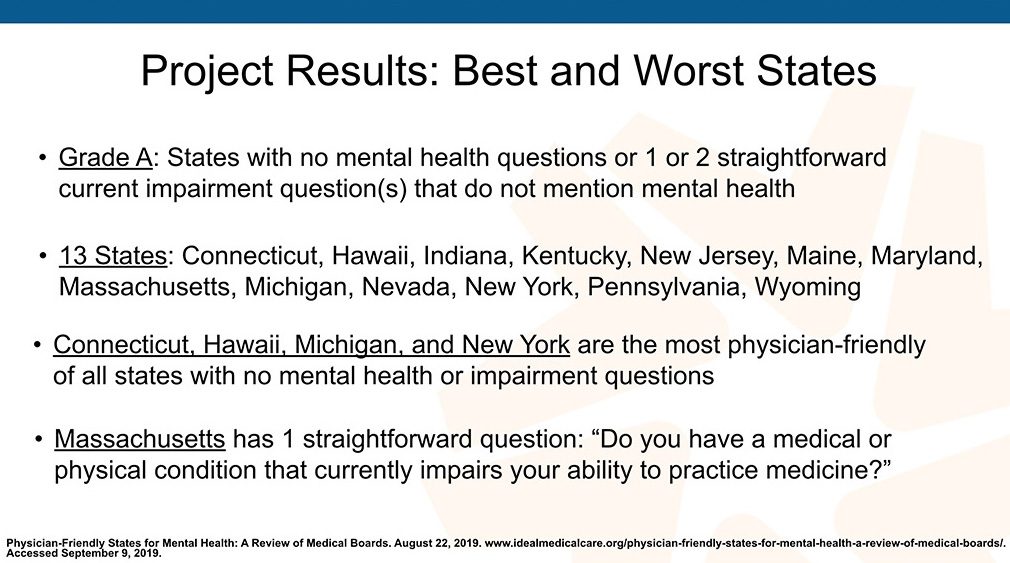

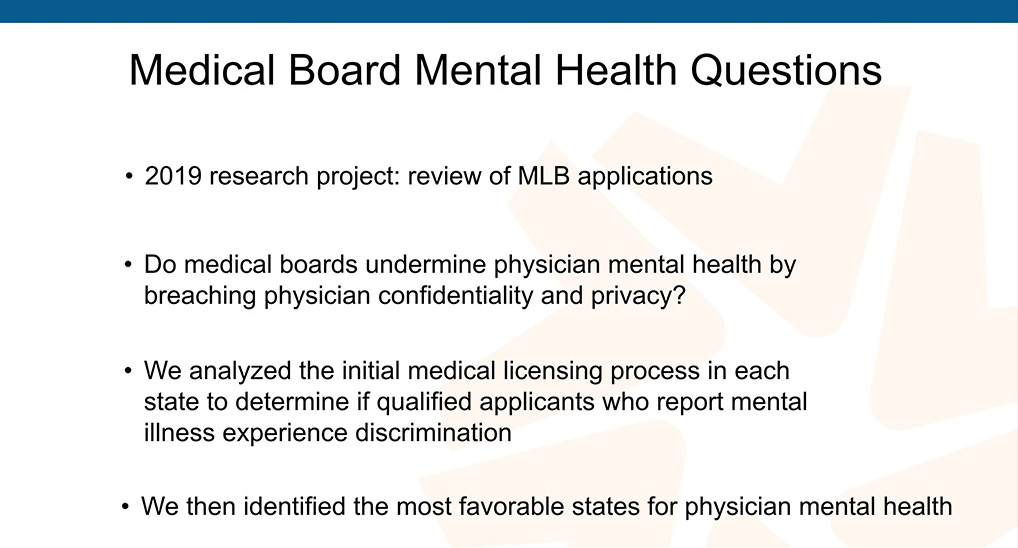

This summer I did a research project on medical boards mental health questions. I want to give a big shout out to Arianna Palermini, she is a medical student who called me up and wanted to work with me all summer on any sort of project. I said, “Well, grab every single state medical board initial licensing application and pull out the mental health questions, let’s analyze them state by state. Read full research study here.

So our overarching question was, “Do medical boards undermine physician mental health by breaching physician confidentiality and privacy?” We analyzed all these applications.

We identified the most favorable states for mental health. Here are three questions to get you thinking about this:

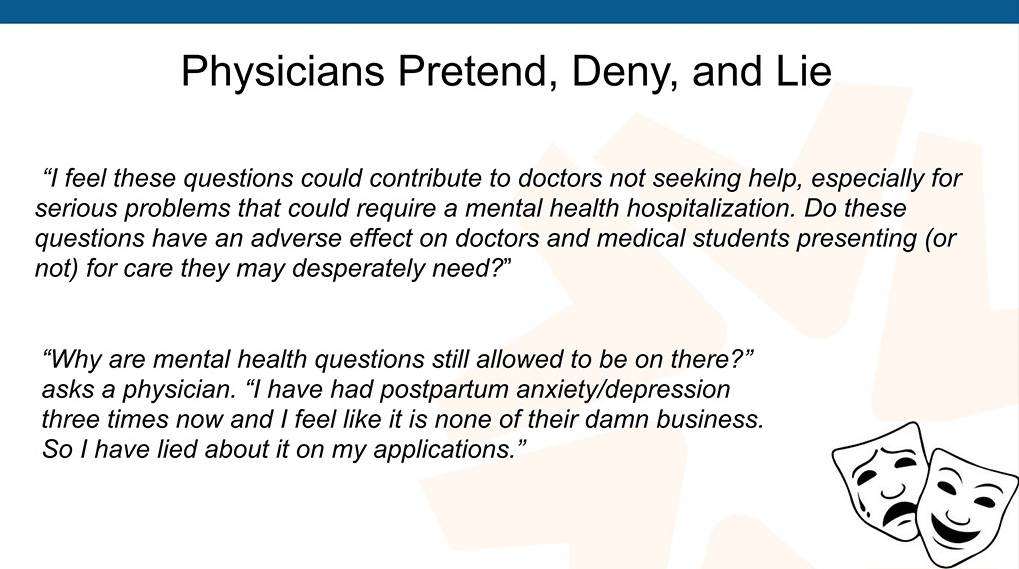

This is a big problem. Violation of our rights to confidential care. So what physicians do is they pretend, deny, and lie. Okay, that’s what we do.

This is the reality of people. I know, many of you in here are lying on their applications. You’re with the majority of docs who have mental health issues. I mean, it’s what people do.

So physicians sneak off-the-grid care.

So physicians sneak off-the-grid care.

How freaked out do you have to be to sneak care in one direction and then drive a 100 miles in another direction to nervously fill prescriptions for antidepressants?

We also have super-honest physicians. A lot of people are just lying, sneaking meds, getting prescriptions online, right, but then we have this whole other group—the really honest physicians, like they’re so honest that they want to correctly check the no box, so they will withhold getting care because they want to be honest on their applications because that’s their philosophy of life and their religion and all that, so they have to be honest, right?

How humiliating is that for an introvert who didn’t even have the problem as an anticipatory decision to take the med? I mean, you wouldn’t really believe this unless you’re on the suicide helpline, you hear these stories all the time. They become more believable but when I started all this, all this stuff seemed like the Twilight Zone, like unbelievable. The same woman above reports:

Would you all agree this is a culture of shame created by our own industry? How are we going to be there for school shooters and veterans and everyone else if we are tormented within our own industry? We certainly have to start here first, I would think.

These “approved” doctors and facilities are part of a larger issue with a conflict of interest, kickbacks, lots of things going on with these “approved” programs. Get on my website. Talk to me later. There’s more, much more to this. [Read about why doctors fear physician health programs here—and view TV investigative reports on what happens to vulnerable doctors.]

Do we really want to create a situation where physicians are scared to get medical care? That’s what we’ve done.

To summarize here, we’ve got three problems. Physicians are self treating and lying, which is a problem, because most of them are not psychiatrists and even if you are a psychiatrist, self-treatment probably not a good way to go. Physicians sneak off-the-grid care and I should have put and lie on that one because the top two are forced to lie and these are people that really probably don’t want to lie, but they feel forced to lie. Then we’ve got the whole big group of honest physicians who won’t get care because they want to tell the truth and they want to check the no box.

Every way you slice and dice this, it’s a problem and so here are the results from this investigation, this research project that we did. This was really fun. What we got to do, I mean it seemed painful at the beginning, especially if I was going to be the one pulling all these reports but thank God a medical student helped me, Arianna, who is a Godsend, but what we did is we actually graded the states from Grade A through as it felt really pleasurable to grade medical boards. You know, after we’ve been graded so much ourselves by just every regulatory body out there. I was like, “Whoo, this is fun. I’m going to grade the medical boards.”

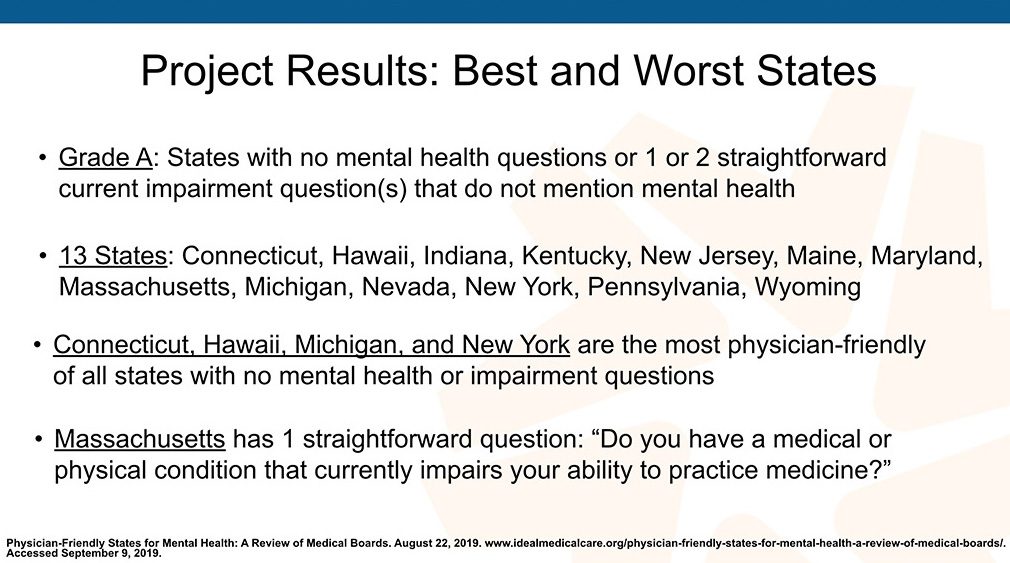

Grade A states had no mental health questions or one to two straightforward current impairment questions that do not mention mental health. 13 states fell in that category. This is a little dense but just go to IdealMedicalCare.org, you can read the full version of this 9,000-word piece with all the hundred comments afterwards and adding your own, if you have an experience. Read full article.

What’s really interesting is Connecticut, Michigan, New York, and Hawaii are the most physician friendly of all states. They ask no mental health or impairment questions. There is the precedent that four states are not asking any questions. In fact, my call to Hawaii Medical Board, it was just so relaxing, because they were like, “Aloha,” which was very different than different from what happened in Alaska, which was 25 yes-or-no mental health questions. Maybe some of this has to do with the climate. I don’t know.

I list Massachusetts here because it’s an example of a straightforward question. The other problem is so many of these mental health questions have multiple commas, clauses, you can’t even figure out (even as a pro at multiple choice questions) you can’t really figure out what the question is aiming at except your career. So this is an example of a question that makes sense. “Do you have a medical or physical condition that currently impairs your ability to practice medicine?” That’s a question anyone can understand and I think that’s good wording.

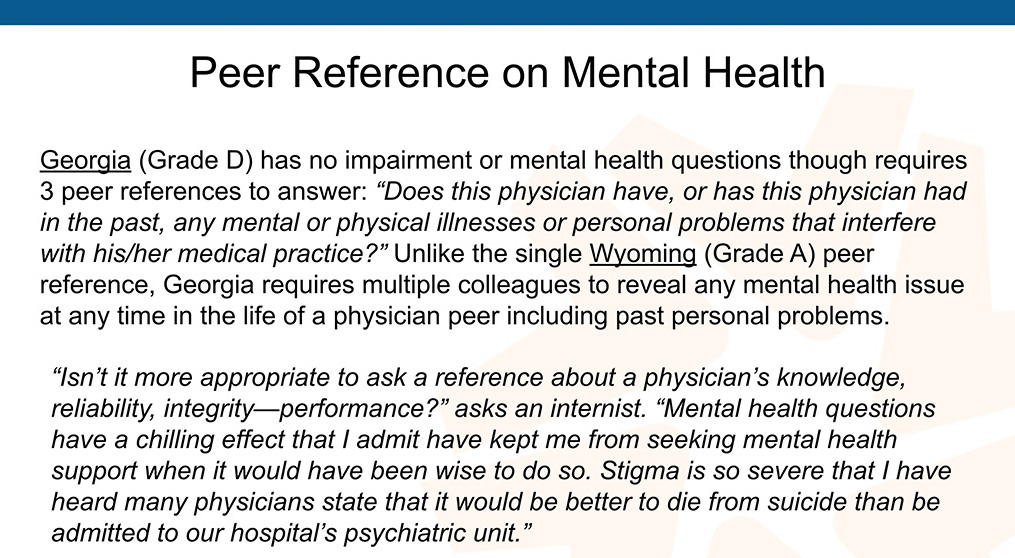

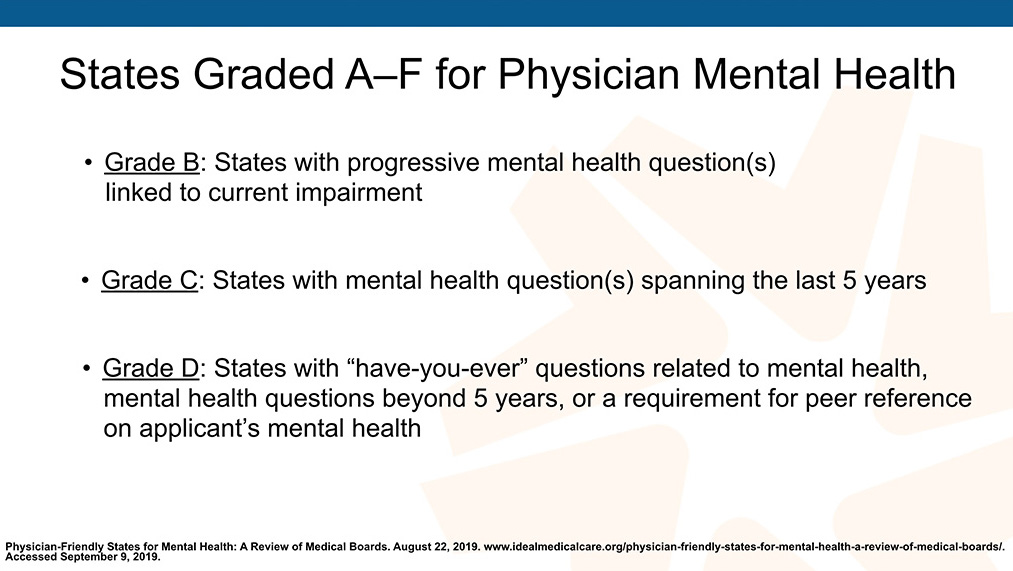

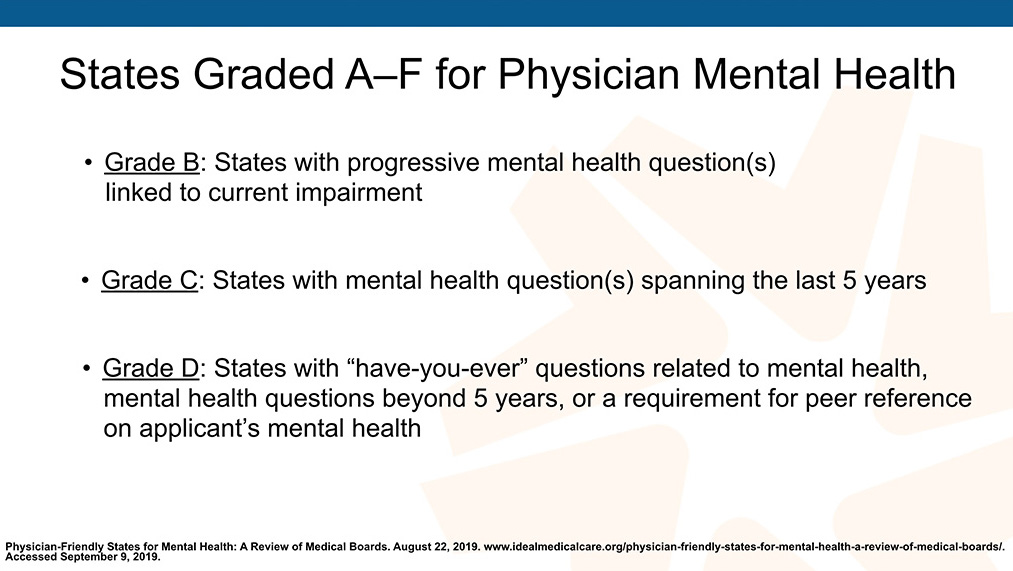

Grade B are states have progressive mental health questions so they mention mental health but they link it only to current impairment. Grade C states are states with mental health questions where they want to know your mental health for the past five years. Grade D states that have, “Have you ever had questions,” related to mental health, beyond five years or like in Georgia they require peer references where your friends who you work with in the next cubicle get to write about your mental health for you, which is very unnerving and they’re not even psychiatrists, at least most of them, as you know, so it’s a problem.

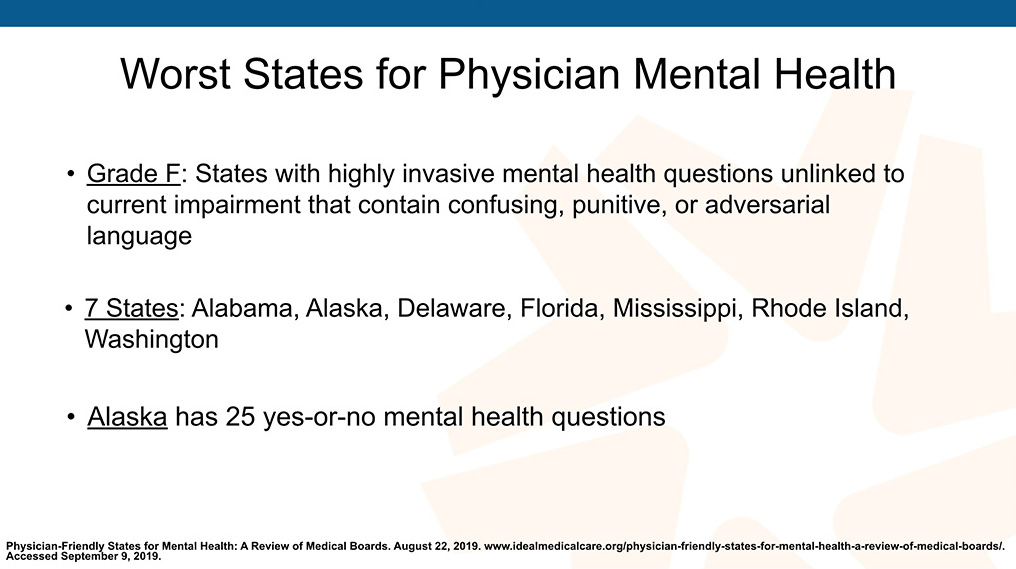

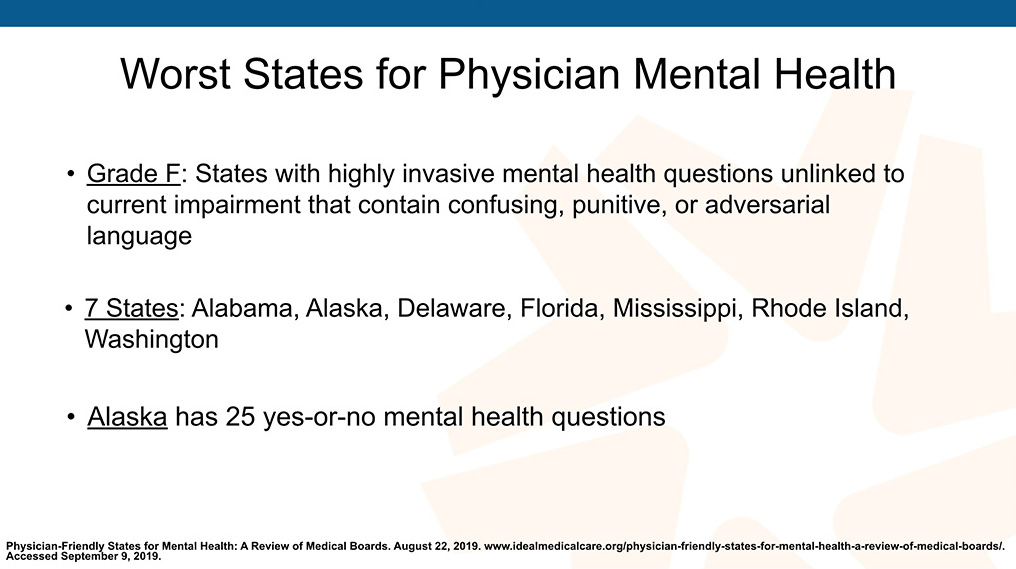

Here are the worst states: Grade F states and you can see all the states that fit in every category. I didn’t want to burden the slide show with all sorts of detail but I want to do this in the A and F states, just so you could get an idea. These are states with highly invasive mental health questions. Probably each one has 12 commas in there. Unlinked to current impairment. They contain confusing, punitive or adversarial language and we have Alabama, Alaska, Delaware, Florida, Mississippi, Rhode Island, and Washington are the worst.

Alaska has 25 yes-or-no mental health question and is the very worst when it comes to mental health licensing applications and I only looked at the initial licensing applications, to have them analyzed, it took all summer just to do the initial. I didn’t do the renewals. Here are some examples of things people have to say.

I just want to say these are physician health programs these doctors are sent to where you end up in a room with two people with a 10-month community college degree who hold your license hostage and can give you a mental health diagnosis (yet it’s not considered practicing medicine) and then you could lose your license.

I just want to say these are physician health programs these doctors are sent to where you end up in a room with two people with a 10-month community college degree who hold your license hostage and can give you a mental health diagnosis (yet it’s not considered practicing medicine) and then you could lose your license.

This is just total crap. I can’t believe this is going on. The first time I heard about it I thought the person I was talking to was delusional, then I heard it again and again in all these different states and like we have a really big problem with physician health programs. (Note: Some physician health programs have helped doctors with substance abuse issues but not for postpartum depression).

Can you tell I’m a little angry? I am angry about this. I think we should all be furious about this. I think psychiatrists should be at the helm of changing this. I’m happy to help, do my little part as a family doc in Oregon. Please help me.

This guy couldn’t even date because women would look me up online and see all this stuff.

I mean, this is so unfair. The peer reference on mental health is from Georgia which is a Grade D state. They don’t have an impairment or mental health question for the physician, but they want three of your cubicle physician friends to answer, “Does this physician have or has this physician had in the past any, ever, any mental or physical illness or personal problems that interfere with his or her medical practice?”

Do you think Ben Shaffer is going to go tell his colleagues he’s struggling if they might have to fill one of these out. I mean this is a deterrent, a huge deterrent. Now Wyoming is a Grade A state and they require a peer reference but they don’t ask anything about mental health. It’s just a straightforward competency question. That’s fine, I’m not against peer references but stop getting in everyone’s business with their psych history.

The stigma is so severe. I have so many examples. Why not focus on what we really want to know. Are you safe with patients? These questions pose barriers to seeking mental health care. They create collegial distrust when physicians fear revealing their struggles with peers who may report them to boards so here’s the solutions. Here’s what we do.

We’ve got to remove these mental health questions. This is the number one thing, if we could do this, oh, our profession will be so much better and we won’t lose so many people. Please, I’m begging you. Get rid of these illegal questions, if you’re in one of those states. [Find where your state ranks here.] Over half the states still have these questions that violate the Americans with Disabilities Act. Call all your smart attorney friends. Get them on this and we need to be actively petitioning. You know what, some of these states you can’t even get them on the phone. Aloha was really nice, Hawaii, but like Washington is an F and some people didn’t really think Washington deserved an F. We have been trying to call them. We haven’t got a call back in many weeks.

I mean you can’t even get a hold of these people and then some of the states, were like, “Well, we’ve updated our language,” but you go on their website it still has the discriminatory questions. “You still have the 2012 version up on your website,” and then they have this long my-dog-ate-the-homework story about why it’s not updated. I have a website. I can change things immediately. If there’s a typo. I can go in there right now and change it. I don’t know why it’s taking some states three years to update wording on a question that they decided they were going to update at a committee meeting three years ago. They do this. There are several states that voted to get rid of illegal mental health questions and the questions are still on there.

Here is the question that I would suggest we use, “Do you currently have a condition that impairs your ability to practice medicine?” It’s very simple, straightforward. Comply with federal law, it’s called the Americans with Disabilities Act, or follow the best practices of Grade A states or maybe the four states that don’t have any of these questions.

Then there is pedophilia and criminal or predatory behavior. Move those to the criminal section, okay. Don’t put postpartum depression and anxiety and seasonal affective disorder next to a DUI and all these other felonies. I mean that’s stigmatizing mental health as a crime. Check out what this one doctor did. I love this guy:

These invasive mental health questions are found beyond medical boards. We have to answer these questions when applying to be in network with insurance companies or hospital credentialing. Once we remove illegal questions at the medical boards, we should across the board get rid of these invasive questions everywhere. So be on the lookout for mental health questions and circle them and make a stink and get them removed. Once people realize this is a problem, physicians are willing to change these questions.

Here are three solutions. Number one, get rid of these illegal questions. Number two encourage everyone to get non-punitive confidential mental health care. I think everyone in a high-risk professions—fire fighters, police officers, all of us in high-risk professions—where we see terrible things, should all be in therapy or have a therapist on speed dial. Should doctors in New York be calling Pamela because they can’t figure out who they could talk to in New York? I mean that’s a population dense state. There’s got to be someone there you trust, right? I mean, I’m happy to do it, but it would be so much easier if there was local help.

So most physicians enter medicine as humanitarians with noble intentions, let’s help physicians be well. How can we as physicians give care to patients that we’ve never received? I’m going to take a breath because that’s important, to breathe and also to allow you to understand what I’m saying.

So the final quote from a surgeon I spoke with the other day:

Finally, my big overall plea that we could all start doing today, I mean I wish I could snap my fingers and get rid of these questions on medical boards. If anyone’s a hacker and knows how to get into these systems, we could get in there and take all those questions off tonight, just talk to me afterwards.

The other one, non-punitive mental health care, please open your office doors, consider seeing your colleagues and keeping this confidential but the most important thing that we can all do today, immediately after this session, into the evening. I’m going to be here till tomorrow. If you want to go out to dinner, let’s all hang out. I’m happy to be your best friend, and we can keep talking about this forever. I’m a late-night person. I stay up till 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning.

If you can DSM me, great, I’d love to know what’s wrong with me, but anyway, what we really need to do is share our stories. It’s therapeutic for you and it’s therapeutic for your colleagues. They’ll be like, “Oh, I’m not the only one.” It creates collegial trust and bonding and it destigmatizes physician mental health, and I would really like to ask that we, at least in this family, at the Psych Congress feel safe enough to take off our mask and be human with one another, we can do that here, I believe with safety.

Here is the summary. Three simple things we can do. Remove mental health questions, number one. Number two, encourage nonpunitive confidential care and share your story.

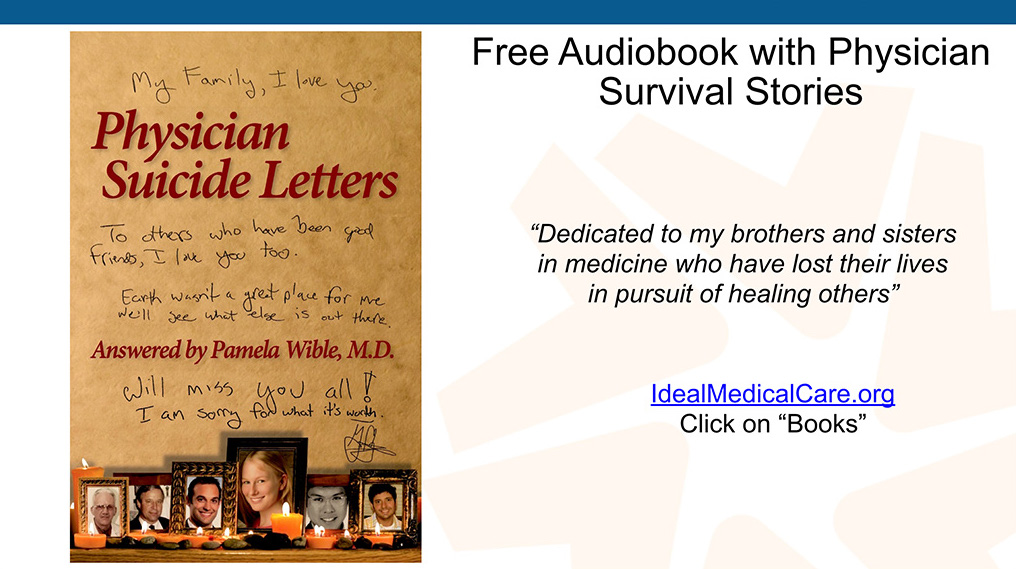

I have a free audiobook for all of you, which has 53 chapters of physician survival stories. I know it sounds terrifying, the title Physician Suicide Letters. You’ll hear me, my voice lulling you to sleep, maybe it’s better than reading a psych journal and looking at Valium ads as a bedtime story. A few of the people in the book have died by suicide and their parents, of course, gave me their suicide letters and asked me to please publish them.

The rest of them are people who contacted me and I do not use any names in here (outside of the real names of the suicide victims with family permission) so you don’t know who the other still-living physicians are. I altered their identity a bit. They wanted to share their stories with other physicians. The book is like being a fly on the wall on my suicide helpline. “What does Wible do? What is she doing in the woods?” Well, listen to what I say and do and you’ll get a sense of who I am.

I think I’m much more mature now than at the time I published this book back in 2016. I understand this topic a lot better, The book was sort of my initial outrage, like “I can’t believe this is happening and here are some true stories,” book.

I will end with another plea to please help me get all these dead doctors out of my house. I love them, I just don’t have space for this many people in my house. It’s a small house.

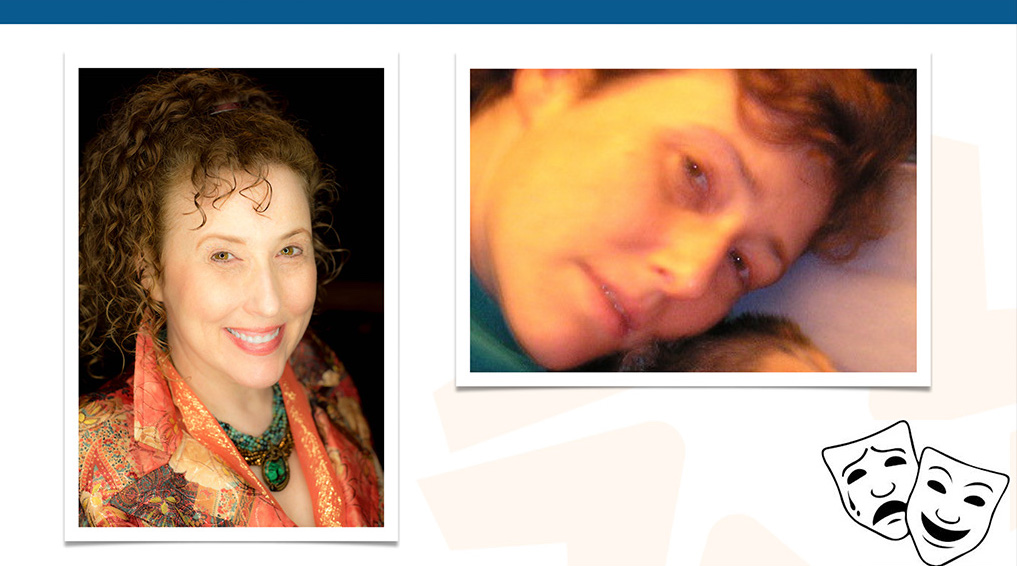

My final slide. I’m going to show you, this is a happy doctor. I’m also going to show you, so you understand what a suicidal doctor looks like, so that’s me in 2004. That’s how I looked laying in bed for about six weeks, so that’s a real suicidal doctor. Problem is we don’t see doctors walking around looking like this. You’d have to sneak into their house, take a picture of them.

Some suicidal doctors have sent pictures of themselves to me as they are sobbing on the bathroom floor with just snot hanging out, like just absolutely on the edge of death and they’ve sent me pictures of it. I don’t have permission to share them. So I’m going out on a limb here, sharing my story in hopes that this will inspire all of you to take out your really depressing pictures and show people that you’re human, yet you are still a competent doctor that can run an ICU and help your patients and you actually do cry at night and you have survived being anxious and suicidal—and that actually makes you a better doctor because you actually understand what it’s like to be human and patients want human doctors.”

Psychiatrists reaction to our closing session:

So physicians sneak off-the-grid care.

So physicians sneak off-the-grid care.

I just want to say these are physician health programs these doctors are sent to where you end up in a room with two people with a 10-month community college degree who hold your license hostage and can give you a mental health diagnosis (yet it’s not considered practicing medicine) and then you could lose your license.

I just want to say these are physician health programs these doctors are sent to where you end up in a room with two people with a 10-month community college degree who hold your license hostage and can give you a mental health diagnosis (yet it’s not considered practicing medicine) and then you could lose your license.