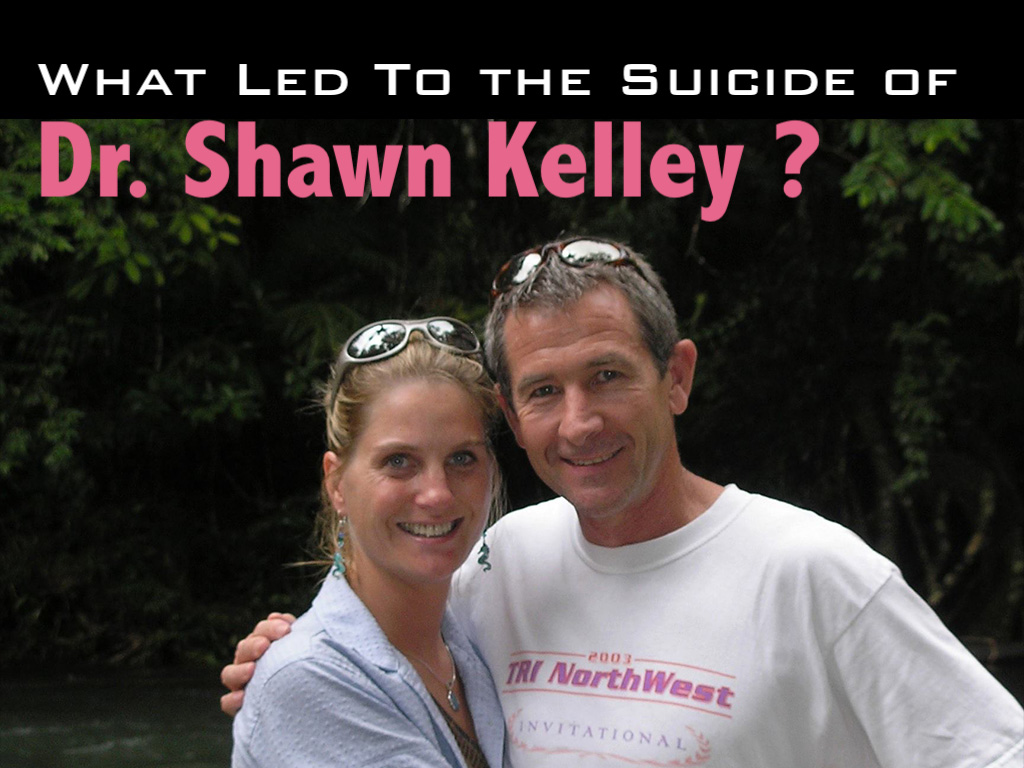

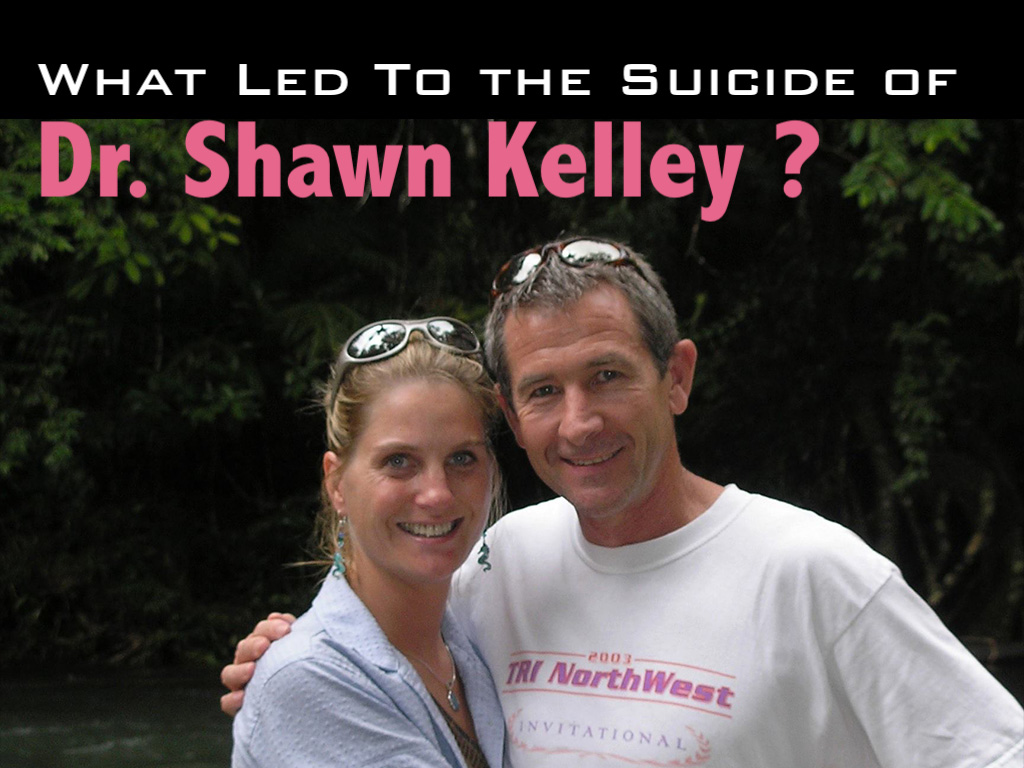

Shawn C. Kelley, M.D., died by suicide under the care of Washington State Physicians Health Program. She was referred to the WPHP based on one unsubstantiated allegation unrelated to patient care. Her husband shares his thoughts and experiences about the program tasked with protecting his wife—and he appeals for a more objective and transparent process for helping vulnerable physicians. (interviewed on date 9/20/19)

I’m Vince Nethery, professor of clinical physiology, and my wife Shawn passed away six years and 55 days ago. I received a phone call at midnight on a Saturday night, and that’s never a good time to receive a phone call. It was from a law enforcement group in Seattle informing me that she had passed away. I got in the car and drove to Seattle. The circumstances that led to this are complicated, multifactorial, and questions come up all the time. We will probably never get answers to many of the questions, even today, six years later.

Shawn was a loving wife, tremendous mother of two children, 1,000 patients or more lost their physician, the medical community of North Central Washington lost one of their longtime members, and how this all came about, as I mentioned, we’ll never know. What we do know is that there are circumstances that led to some level of discontent in the workplace with one particular individual. That individual filed a complaint to the medical director of the hospital. Later we learned the complaint had something to do with an out-of-work experience. It was a private function that had nothing to do with the workplace. The complaint expanded to the workplace with the individual saying they would never work with Shawn again. We asked for an investigation to say, “Well, what’s the basis of this? Give us a root cause analysis of the situation. See how many others were affected by some allegations of . . . I don’t really know what they were, but whatever those allegations were.

Ultimately, Shawn was directed to go to the Washington Physicians Health Program. She wasn’t exactly sure why, but she was directed to go there and based on that directive she had no choice but to go. She met with two individuals in a conference room and those individuals discussed or asked or interrogated her, I don’t know, I wasn’t there, for about 45 or 50 minutes. At the end of that time period, the medical director of WPHP came into the room and within five minutes indicated that she was to go to an inpatient facility within a few days [Note: she was to pack her bags, leave her family, and travel to Georgia to enter their “preferred” inpatient facility at her own expense for four days. She was not given a diagnosis or a clear reason for their decision].

She walked out of there. She called me. I remember it as clear today as it was then. She was incredibly upset, as anybody would have been I would think.

We communicated about how it went and I asked her what was the basis for the directive that came from the psychiatrist at WPHP. She indicated that he was in the room for maybe five or 10 minutes and when he made the directive to her that she needed to go, she asked why, and he indicated to her that her speech was pressured or pursed and that was the basis for his evaluation. I wasn’t exactly sure what that meant so I asked Shawn and she indicated that, “Well, that’s usually a sign of stress, that you have pursed or pressured speech, and it’s a sign of stress.” And she said, “Well, how do you think I would be? I just spent 50 minutes in this meeting having these fairly one-sided conversations with two individuals and I was stressed out. It would be unusual for somebody not to be stressed.”

I asked her who the two individuals were who were in the majority of the conference meeting with her and she wasn’t sure. She knew the names because they introduced themselves, but she didn’t know what their role was, what their qualifications were.

A subsequent meeting with the medical director of WPHP many months later where I accompanied Shawn to that meeting, I asked the medical director who the two individuals were.

His first response was, “They are professionals in WPHP.”

I said, “Okay, are they trained psychiatrists?”

He said, “No.”

I said, “Well, perhaps they’re psychologists, right, they’re certified through psychology?”

He said, “No.”

I said, “Well, do they have a bachelor’s degree?”

He said, “They have a substance abuse certification.”

I said, “Okay, how do they get that? What level of education do they need to get that?”

He said, “They received that through a program at a local community college.”

I said, “So we’re making a decision that’s going to have a significant impact on somebody’s life here on the basis of 45 minutes of questioning discussion with two individuals who have a community college certification. That doesn’t seem right, does it?”

He said, “They’re professionals in our organization.”

I then followed up with the medical director and I asked him, that given the heavy emphasis in medicine today and for the last decade or more, on evidence-based being the base for making critical decisions, I asked him to explain what the evidence base was for the medical decision that he made. He got up and left. Came back five minutes later and said, “Our meeting is finished.”

We had spent about 90 minutes in this meeting with him to try to get to the bottom of a basis for his decision. He would not provide a rationale for it, none whatsoever. He provided no evidence to support it beyond the hearsay or the allegations made by a single person that were unsubstantiated in a following followup investigation of the setting in which this individual worked.

I was flabbergasted, actually, that an individual who had so much quote unquote “power over” the functioning of a physician could make those types of decisions and make them without being able to provide a justification, especially to the person to who that decision was being rendered. I’ll take a break.

Of course with 20/20 hindsight there are probably some things that might have been done in a different way that may have averted the outcome that did exist. One area I personally think would have benefited this particular situation would have been the development of a clear pathway to the resolution. That is, what are the specific areas that need to be addressed and completed in order to have a return to normalcy of the workplace? It seemed like we were forever chasing a moving target. One thing was asked to be done, it was complied with. At the end of that, there was another thing, and that was done. Then there was something else. And at the end of the day there was no clear pathway to resolving the matter and allowing individuals to return back to a professional environment that they were trained to be in.

In addition, the establishment of an ombudsman type of person within the setting to provide an objective evaluation of it without the workplace evaluations being conducted by essentially some of the individuals who were inherently at the root cause of some of it. And that didn’t exist. There wasn’t an objective individual who was doing a root cause analysis to find out at a very basic level the underlying factors and the veracity or lack thereof of the allegations that were made.

There was really no support provided from a physician perspective. Shawn felt like she was out there like a shag on a rock. Just at the whim of whatever direction the wind was blowing. To put a more defined mechanism in place and to have a clear set of directives that need to be addressed, to find out whether they need to be addressed, and then determine the pathway to follow for addressing them, if there is validity to them, would have been extraordinarily helpful in this case.

Questions that remain unanswered:

1) Why is it that one disgruntled individual in a social setting can leverage a complaint (unrelated to patient care) against a competent physician and undermine a doctor’s entire profession?

2) Why are two individuals with 10-month community college certificates in charge of determining the fate of a doctor’s career in 45 minutes?

3) Why are physician health programs not using evidence-based medicine?

4) Why is there a lack of transparency in physician health programs so that the physician and family and not given a diagnosis and treatment plan with a clear pathway to resolving the unsubstantiated allegations against the doctor?

5) Why are physician health programs unwilling to answer questions about physicians who have died by suicide under their care?

If you have answers to these five questions, please share your insight below as Dr. Shawn Kelley’s family deserves to know what happened to her.

Questions raised about physician health program safety:

Doctors fear PHPs—why physicians won’t ask for help (TV report)

Physician Health Programs: More Harm Than Good

Physician health programs: ‘Diagnosing for dollars’?

Top 10 things you need to know about PHPs

After investigating more than 1,300 doctor suicides during the last seven years, I’ve noticed a disturbing trend in which physicians have been dying by suicide under the care of physician health programs. Victims are sent to PHPs for unclear reasons, mandated to one-size-fits-all “preferred” substance abuse treatment centers for up to five years at great personal expense—even though many had no substance use issues. If you have been harmed (or helped) by a PHP, please share your story below.