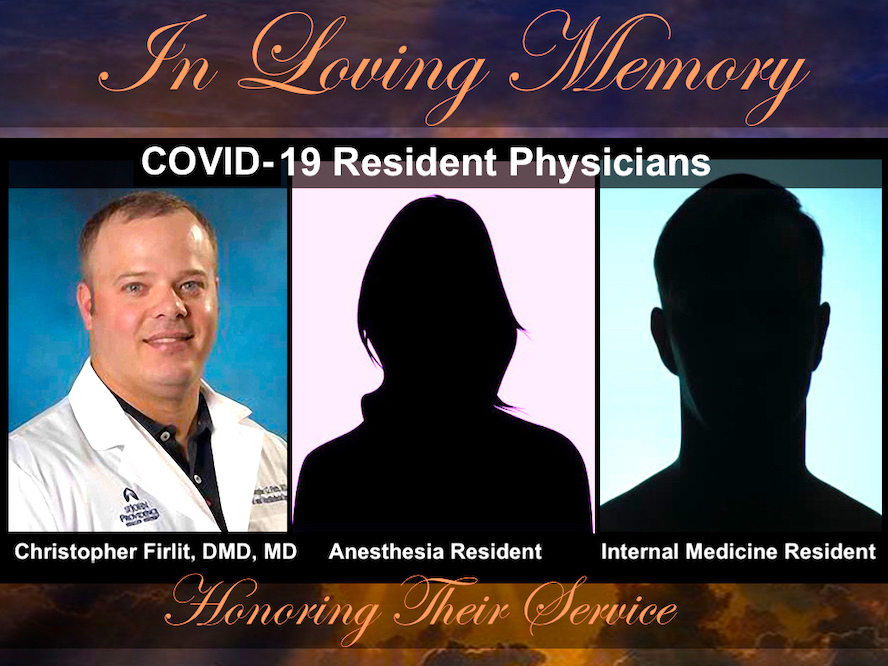

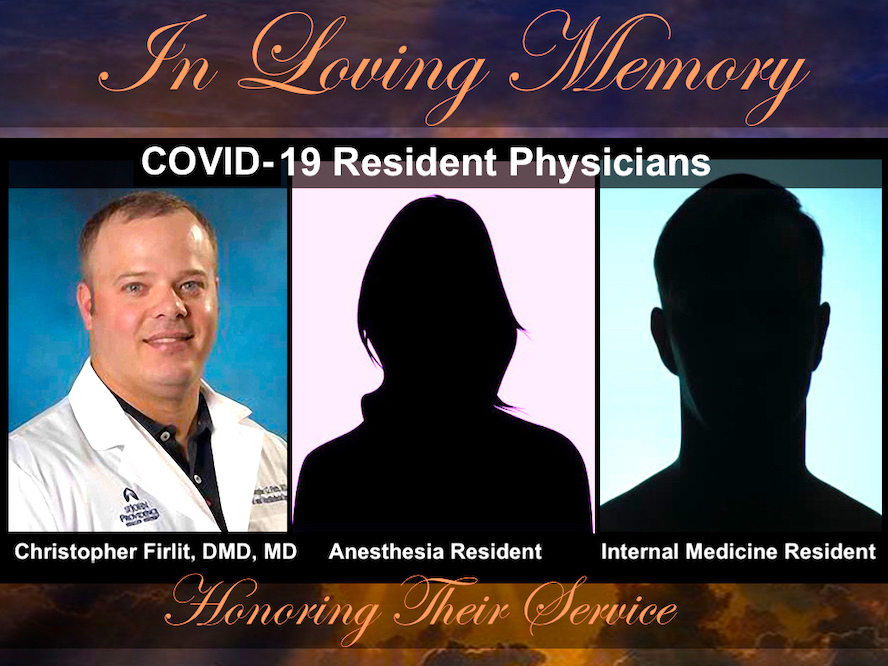

Dr. Christopher Firlit, age 37, a PGY6 senior oral maxillofacial surgery resident in Detroit, Michigan, was to graduate in 3 months. He developed a fever and his chief fellow drove him to Providence Hospital where he died on April 3 of suspected COVID-19. He was employed at Ascension Macomb-Oakland Hospital. He leaves behind his wife and three children.

An Anesthesia Resident in New York City has been reported to have died of COVID-19. A mother, she leaves at least one child behind.

An Internal Medicine Resident in New York City has been reported to have died of COVID-19. A PGY1 male, age 26, with no underlying health conditions ended up on ecmo (a heart-lung by-pass machine) at Montefiore Medical Center where he died on April 3 from a catastrophic brain bleed, according to an ICU doctor. As an International Medical Graduate (IMG) from Pakistan, his visa is sponsored by his employer, reported to be Elmhurst Hospital (Mount Sinai Health System). Recently married, his spouse may now be deported.

It’s been more than two weeks. No media outlets have covered these New York resident physician deaths. Why? Hospitals are censoring doctors—threatening termination for breaching “media guidelines” if they speak to reporters. So physicians have asked me (in emails published with permission below) to honor our fallen physicians:

“I am a resident in NYC. We have heard of multiple resident doctor deaths in the past 2 days (outside of my hospital system). We have heard rumors of gag orders being placed, preventing any publicity around their deaths. It is unclear if they had access to PPE. Could you advise how to stop these resident deaths from remaining secrets when they deserve to be honored? Is there a news outlet we can talk to to publicize this? Please keep me anonymous. Thank you for your help.”

“I am sure others might have contacted you about this issue already because of all of the work you have done on the topic of resident/student deaths from suicide and how it’s not talked about. I am a member of a COVID-19 group on Facebook that has mentioned possibly 3 or 4 medical residents dying from COVID-19 in the last 7 days. In the news there has been one death acknowledged-—Dr Firlit from Detroit. I don’t know if there are actually 3 more young trainees who have succumbed to this but I work with residents/fellows/students and am hoping to prevent further devastating loss. Thank you.”

“Dr. Wible, I was wondering if you’ve been hearing about the eerie silence around resident physician deaths (and physician deaths in general) during the pandemic. It seems that every resident I’ve spoken to here on the East Coast knew within a day that 2 residents had died from COVID-19 after being on the frontlines, but our hospital administrators have been silent. In fact, I know a resident who tweeted a text screenshot from a friend who had heard the news, and is now being reprimanded by her department and was asked to delete the tweet. The most suspicious part of me is concerned that hospitals are working to keep these stories from getting out to prevent residents from losing morale. Or rather, from realizing more and more that we are being tossed around like possessions and thrown into a burning mess created by the government and hospital administrators’ failure to prepare. We don’t even matter enough to them to deserve hazard pay, like our colleagues in nursing are (rightfully) earning when they volunteer. In the same way physician suicides are covered up, I believe our deaths now on the frontlines are being minimized so as to keep us grinding away, unprotected by PPE or workers’ rights. Thank you for all your work in amplifying our voices, when people are losing their jobs and lives left and right.”

I’ve witnessed hospitals cover up physician deaths since 2012 when I began investigating why so many doctors were killing themselves inside our hospitals. For 8 years, I’ve been running a doctor suicide hotline. I’ve now amassed a registry of 1,473 doctor suicides. Root cause analysis reveals hazardous working conditions and human rights violations as the culprit. Predating the pandemic, medicine’s well-hidden physician suicide epidemic became the focus of a now newly released award-winning documentary—Do No Harm: Exposing the Hippocratic Hoax—by an Emmy-winning filmmaker. View the world premiere streaming live this Sunday, April 19 at DoNoHarmFilm.com.

I’m very familiar with censorship by medical institutions. Parents who lost children to suicide during medical training have been given honorary diplomas for signing nondisclosure agreements preventing them from speaking about their own child’s death. One mom told me she was offered hush money by the med school to keep quiet about her son’s suicide. Residents have been threatened with termination for speaking about their colleagues’ suicides.

Hospitals don’t want you to know about these hazardous working conditions that are killing doctors—and patients (especially during the pandemic).

I bet you didn’t know that:

1) New doctors are forced to work 28-hour shifts for less than minimum wage—and they’re the workhorses in our hospitals. After graduating medical school, residents must work up to 7+ years in hospitals, 80 hours weekly (some 100 or more) while severely sleep deprived leading to medical mistakes that have harmed—even killed patients. During the pandemic, residents have been forced to work even longer without hazard pay,

2) Hazardous working conditions cause new doctors to age six times faster than their non-medical peers. Scientific studies prove that residency leads to serious chromosomal damage and a weakened immune system that places new doctors at high risk for illness—including dying from COVID-19.

3) International Medical Graduates are most vulnerable to abuse. Hospitals bank on the fact that foreign doctors from poor countries can’t defend themselves. If they don’t submit to abuse, hospitals fire them and they’re deported. Without local friends and family IMG COVID-19 deaths are easier to hide. Without a local support system, many have no online obituary and no friends posting tributes on social media. Not to mention, how in the world will grieving family members overseas get their body shipped back with pandemic travel restrictions? Devastated families have no emotional (or financial) resources to defend themselves and their loved ones from the criminal practices of US hospitals.

4) Doctors with inadequate protective gear are infecting themselves—and their patients. Asking doctors to use the same mask all week is like asking a gynecologist to use the same speculum all week or asking a prostitute to use the same homemade condom (made out of a trash bag) all week.

5) New doctors with shattered immune systems and inadequate protective gear are inhaling large viral loads. Highest risk specialties include the three doctors honored here—Dr. Firlit, who performs oral maxillofacial surgery as well as anesthesiology residents responsible for intubations, and internal medicine residents running COVID ICUs. Doctors who refuse to submit to hazardous working conditions caring for COVID-19 patients, are fired.

6) When residents die from unsafe working conditions, hospitals should face wrongful death lawsuits. If you’re a resident physician, here’s how to protect yourself from hazardous working conditions. If you need help, please contact me here or join our free support group for medical trainees. If you know the names of residents who have died from COVID-19, please share (even anonymously) as these beautiful people who have sacrificed so much of their lives to help and heal others deserve to be honored, not thrown in a body bag and discarded like medical waste.

Thank you for caring about our healthcare heroes who have died.

NOTE: If anything I’ve written is incorrect please feel free to update me so I can update this with the truth (surprisingly challenging to find out the truth). This is my best guess based on all the people who have contacted me in the last two weeks. Thanks in advance for filling me in on if you know more . . . (there may be more deaths, who knows?)

Addendum 4/27/20: Identities of the two COVID-19 resident deaths remain unknown. One resident wrote me after publication: “So the person that died [IMG] had the same name as a resident at the hospital they were transferred from. (not sure where but either Coney, Elmhurst, Sinai). There was a lot of confusion, even the record here at Montefiore said that the person was a resident.” As of today I am aware of a new COVID-19-related doctor suicide (RIP Dr. Breen) and another doctor who died by suicide after a job fell through due to the pandemic.