Physician, Heal Thy Inner Critic Research Results (video above, data highlights below)

What’s an inner critic?

The inner critic is the internal voice that judges, criticizes, or demeans you, often highlighting your flaws, mistakes, or shortcomings.

Why do so many physicians struggle with an inner critic?

Doctors may have a strong inner critic because medicine demands perfection, punishes mistakes, and rewards self-discipline to the point of self-denial. From early training, doctors internalize high standards and a fear of failure, often pushing themselves with harsh self-talk. Add to that the emotional isolation, burnout, and impostor syndrome common in the field, and the inner critic becomes not just a voice—but a constant companion.

What are common physician inner critic phrases?

Research reveals the most common phrase is “I am not good enough.” Others are: “I should know more about this than I do” and “I must not be as smart as my peers.” Physicians even carry “I’m not good enough” into their personal lives with circulating thoughts of ” I’m not a good enough friend, daughter, wife, mom, doctor.” Reference video above for categories of statements ranked by prevalence. Selected charts published below.

Why identify our inner critic phrases?

Once we become aware of critical self-talk these voices can be silenced. Hypercritical perfectionism, approval-seeking, and self-sacrifice phrases often stem from childhood, and are reinforced by medicine’s demands. Identifying core dysfunctional beliefs limiting your success promotes personal healing and makes us better doctors.

Physician, Heal Thy Inner Critic Research Results

Research results reveal sneaky ways your inner critic can sabotage your career (and entire life!) The good news? You can take your power back. Interviews with 134 physicians by phone, email, and focus group identify common inner critic phrases; when hypercritical voices begin; and how to quiet your inner judge—for good.

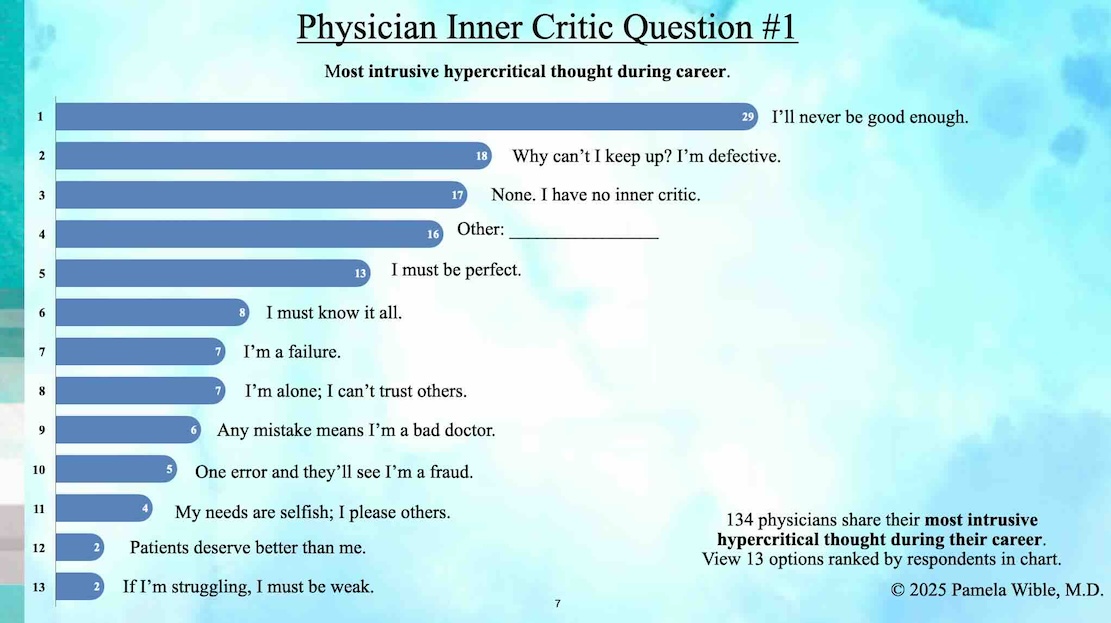

Physician Inner Critic Question #1

Pick one (1–13) that best describes your most intrusive hypercritical thought during your career as a physician:

1. I’ll never be good enough. 29 (21.6%)

2. Why can’t I keep up? I’m defective. 18 (13.4%)

3. None. I have no inner critic. 17 (12.7%)

4. Other: (please share) ________ 16 (11.9%)

5. I must be perfect. 13 (9.7%)

6. I must know it all. 8 (5.9%)

7. I’m a failure. 7 (5.2%)

8. I’m alone; I can’t trust others. 7 (5.2%)

9. Any mistake means I’m a bad doctor. 6 (4.4%)

10. One error and they’ll see I’m a fraud. 5 (3.7%)

11. My needs are selfish; I please others. 4 (3.7%)

12. Patients deserve better than me. 2 (1.5%)

13. If I’m struggling, I must be weak. 2 (1.5%)