On this day of unity, inclusion, and freedom—I am so honored to celebrate our oldest nationally celebrated commemoration of the end of slavery in the USA. On June 19, 1865, Union soldiers arrived in Galveston, Texas, to announce the slaves were now free! On that day, Union Major-General Gordon Granger read this General Order No. 3 to the people of Galveston:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.

As a Texan, I grew up celebrating Juneteenth and I am so dang proud of my home state for being the first to make Juneteenth an official state holiday on January 1, 1980. As a medical student I lived and studied a few blocks away from where this Order was read in Galveston.

I’m also proud of my med school. In 1902, UTMB/Galveston opened the first state-funded hospital for African-Americans in Texas. In 1949, my school graduated the first African-American in Texas, Dr. Herman A. Bernett. My medical school has been celebrated as the most diverse medical school in the country.

I’ve lived more than half a century as a healer on this planet and so on this day of freedom I want to share my reflections on race, unity, and love (originally posted on Facebook on June 4th amid the protests against police brutality).

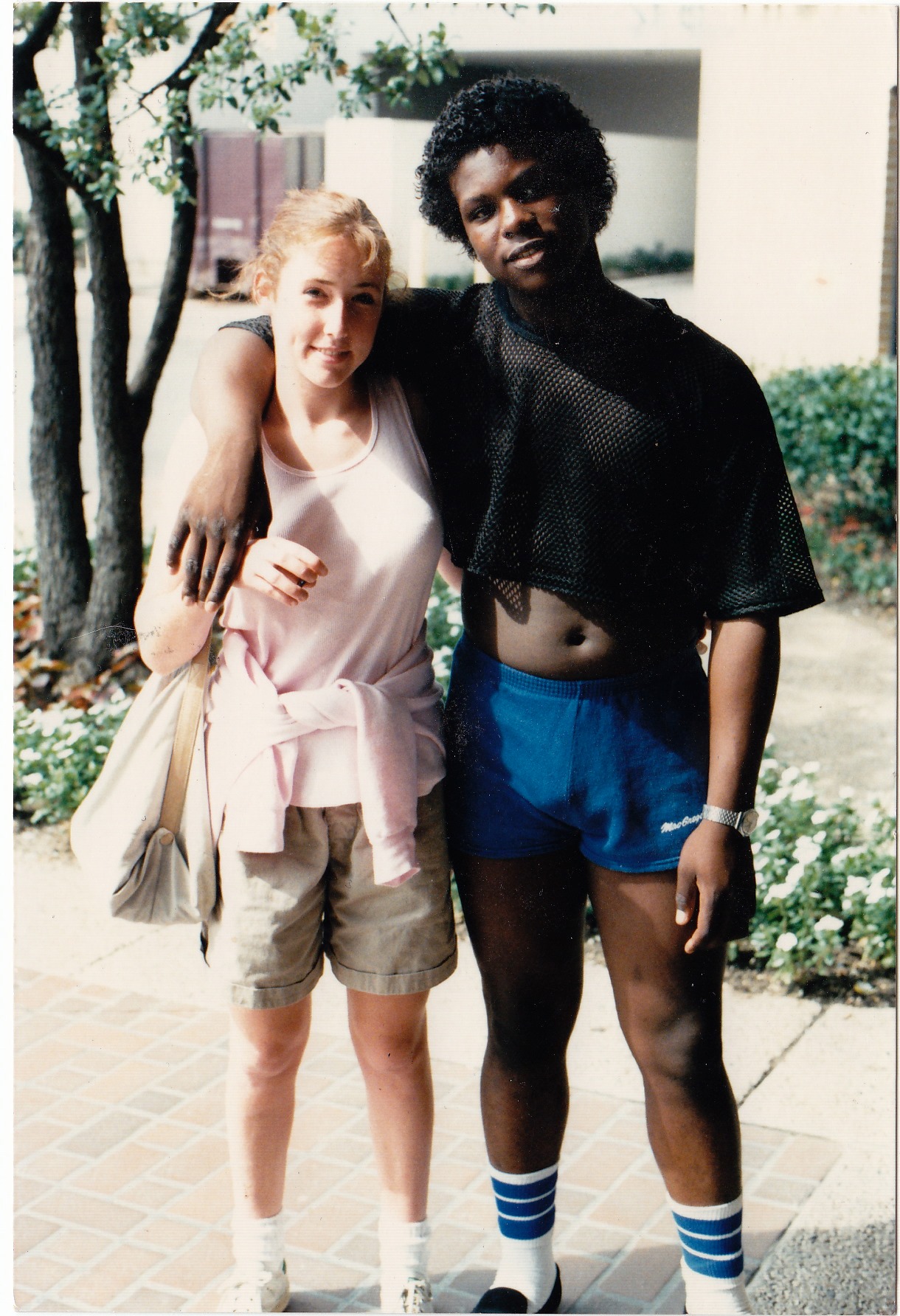

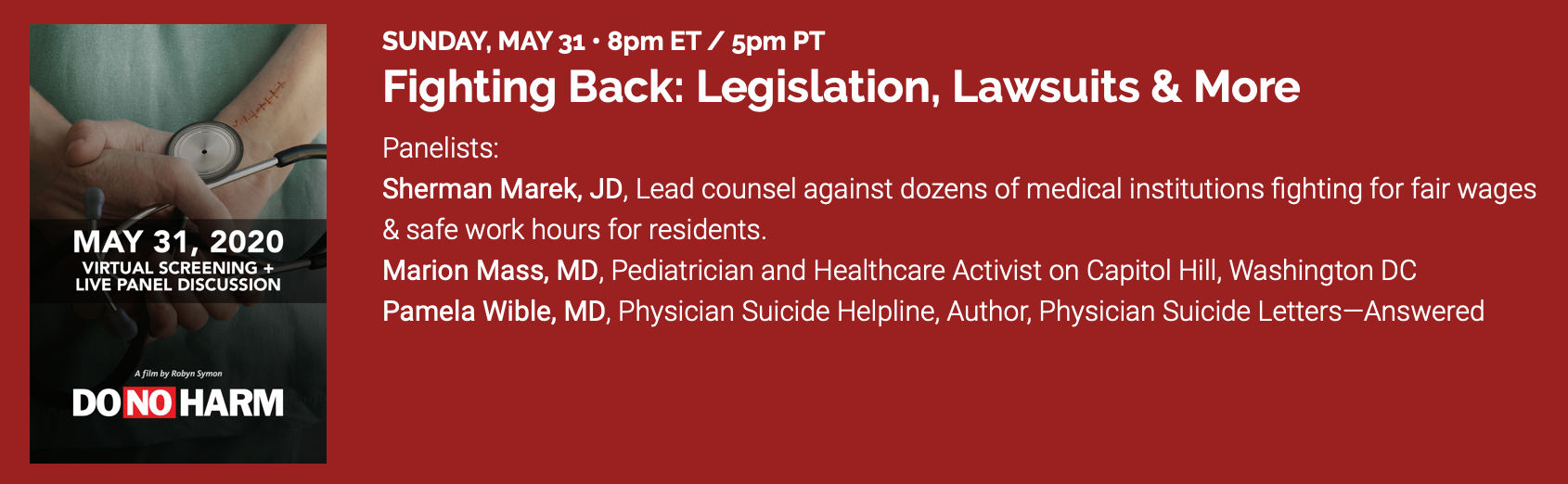

I’ve loved and dated men & women of many colors, races, religions. I live with a black man now. We’ve been together 7 years. I raised a teen foster son—a black man. For a year, I had a homeless black man living with me. Here I am in 1985 with my high school boyfriend, Demetric.

Pamela and Demetric as young teens at the mall in Dallas.

We were both relatively innocent, and certainly young and hopeful. What I experienced with him opened my eyes to what I’d never ever experienced dating white guys. I was 16. He was 14. I was a senior. He was a freshman. We went to high school together in North Dallas near my house. He lived in South Dallas. Neither of us had a car so we walked everywhere and rode the bus to see each other. I recall these incidents as if they were yesterday:

1) Walking through North Dallas, we were often stopped by police (and other random people). They’d ask me, “Are you okay? Do you need a ride home?” Happened over and over again.

2) In stores like Neiman Marcus and even Woolworths security guards followed us around. Only happened with him. Never when I was alone or with anyone else.

3) My friend’s dad pulled me into a room and gave me an anti-miscegenation lecture (his diatribe against racial interbreeding). He recited quotes from the Bible to support his agenda. I thought he was nuts. I’d never belong to a religion that opposed loving someone. Turns out miscegenation was a felony in the US. When I was born (1967), exactly one-third of all states (17) had anti-miscegenation laws —all Southern states (former slave states plus Oklahoma) still enforced these laws. The anti-miscegenation law in Texas was overturned when I was two. it took Mississippi until 1987, South Carolina until 1998 and Alabama until 2000 to amend their states’ constitutions to remove language prohibiting miscegenation.

4) The thing that really stood out to me about my boyfriend’s behavior was that he held his head down in my neighborhood. He always said, “yes sir” and “yes ma’am” and he spoke really really softly. In his neighborhood he was so lively and expressive and free. I felt more comfortable in his neighborhood than mine. I had more fun there and I adored his family—especially his mom who adopted me as her Goddaughter. My neighborhood seemed stuffy and uptight. Demetric was clearly on high alert and scared. The police only stopped us in my neighborhood.

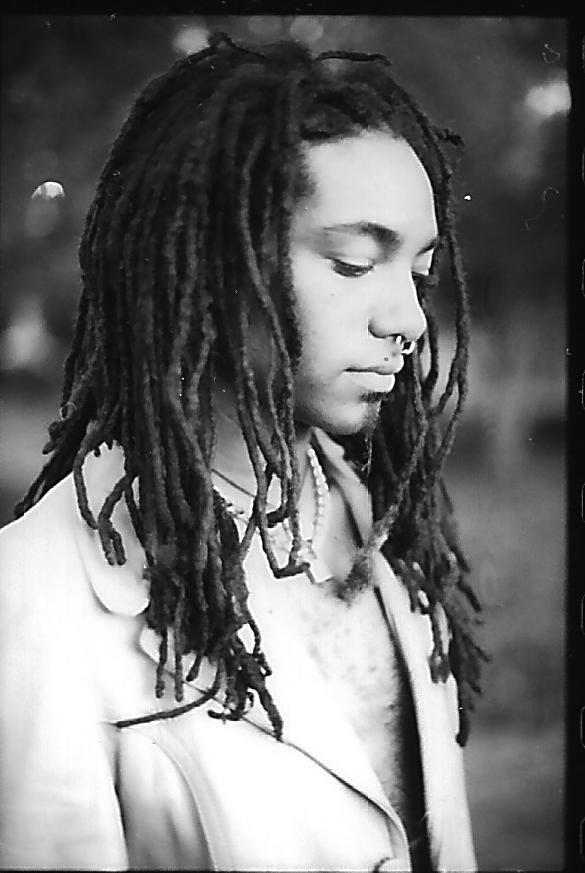

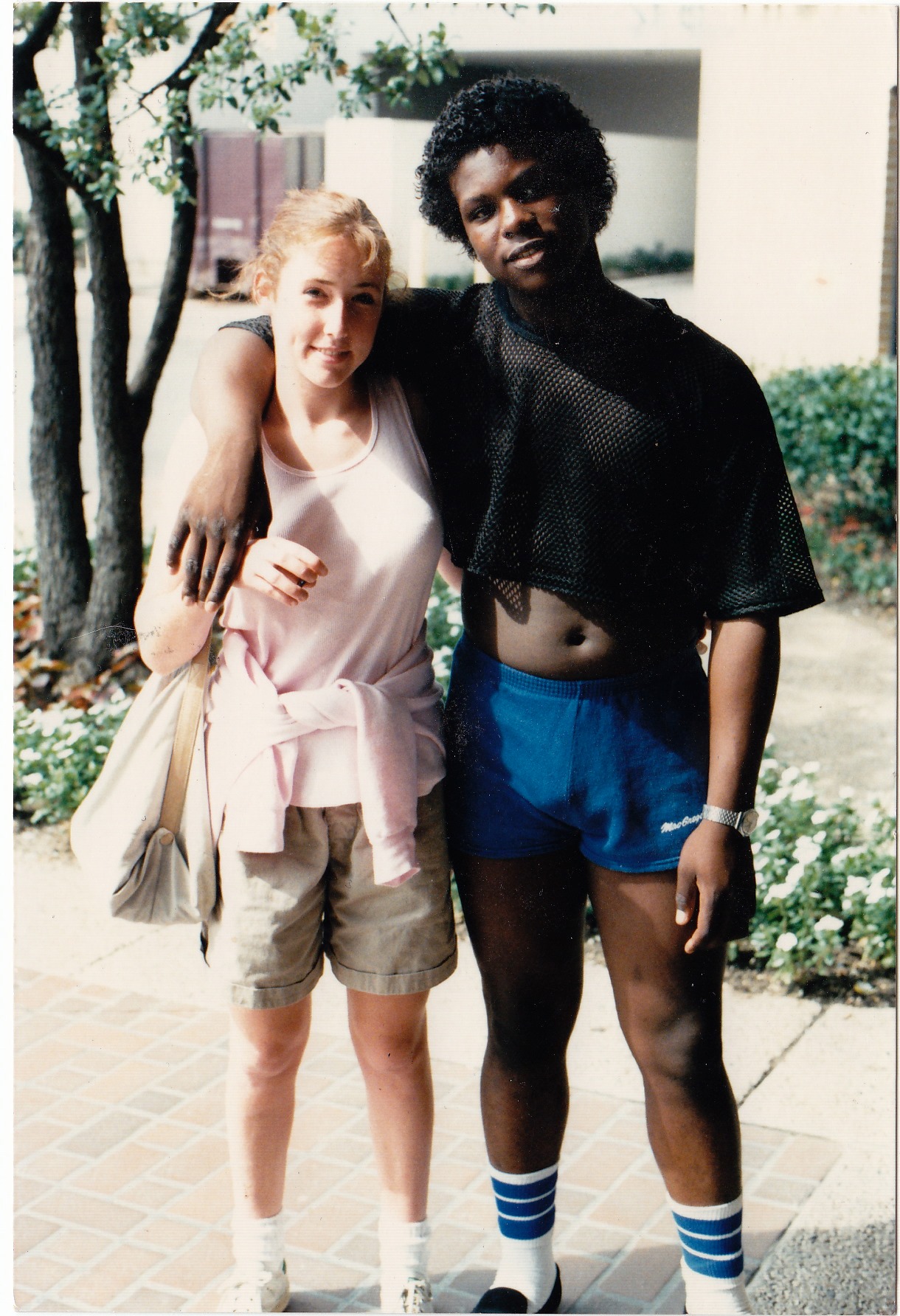

Now, 35 years later I’m with a man who lost his unarmed friend murdered by a cop at his home. My sweet partner below was pulled over by a cop and thrown to the ground with police dogs on him.

My partner around the time he was attacked by police

Why was he pulled over and attacked? He was making a left turn when the light suddenly turned yellow. So in broad daylight two police made him undress down to his underwear with dogs on him, calling him the N word. My friendly, loving, and sweetheart of a man now has PTSD. He tells me, “That’s why I don’t like to go outside.” We’ve only been out to a restaurant a few times in all these years. He feels safer at home.

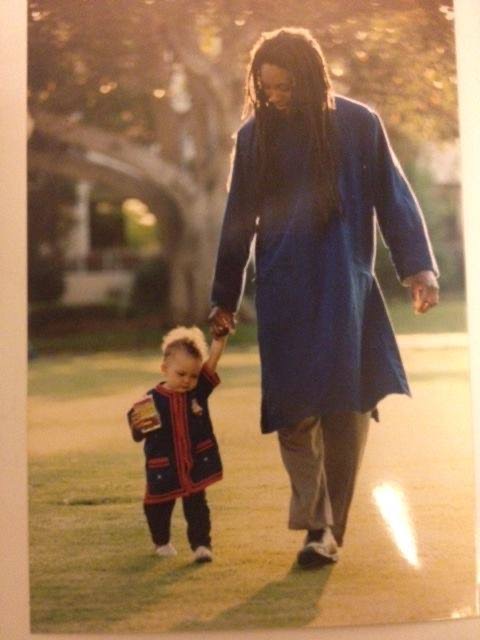

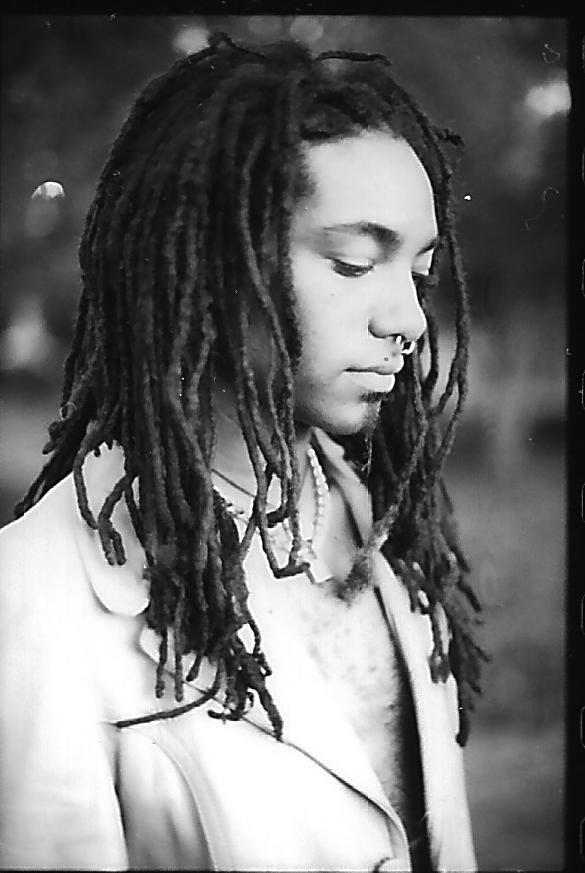

My sweet partner with his daughter—a product of “miscegenation.”

So how are we going to address this as a nation? I don’t favor lashing out at others. I favor looking in the mirror at our own prejudice. Here’s what I mean . . .

Both my parents were upset that I was dating Demetric. Furious actually. Both disowned me during my first year of college. How could my own parents be racist? My mom said it wasn’t about race. It was about class. I’ve never cared how much money anyone I dated had in their bank account. Irrelevant to me.

How could me loving someone be SO disturbing to SO many people?

My maternal great grandfather was in the KKK and according to my relatives “hunted black men for sport.” I had a family member tell my current partner this to his face a few years ago. Racism is taught inside families and passed down from generation to generation. From there it seeps into police departments and every other profession.

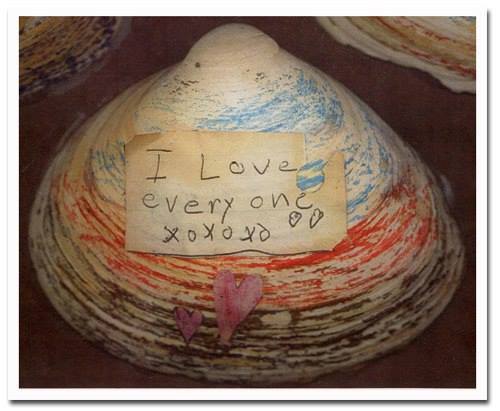

Pamela and brother playing with kids at a fountain in downtown Philadelphia

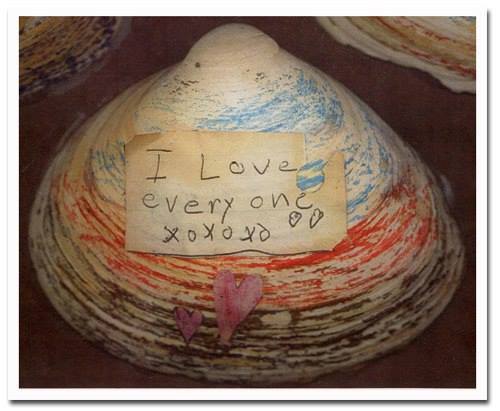

I’ll close with a photo of me and my brother playing at a Philadelphia fountain with other kids on a hot summer day and a piece of my artwork with words I wrote as a child: “I love everyone.” All children start out this way—until they learn from their parents or society to hate and fear others.

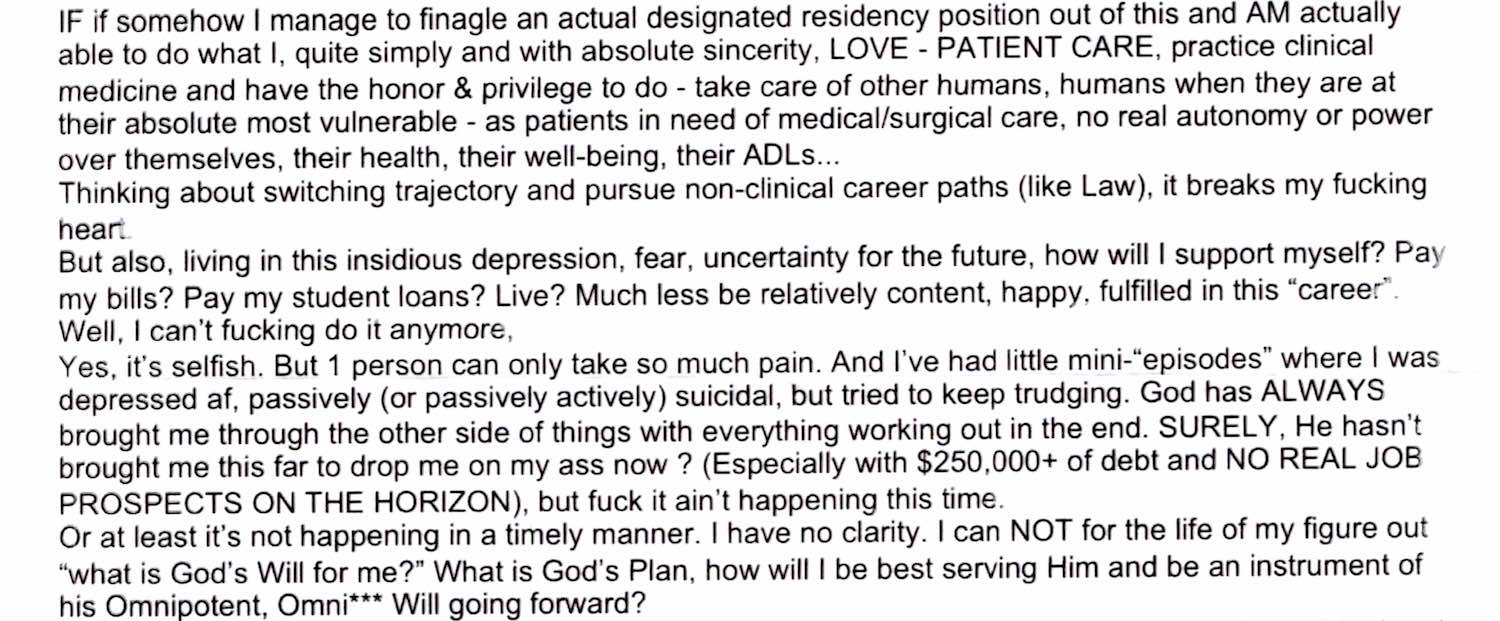

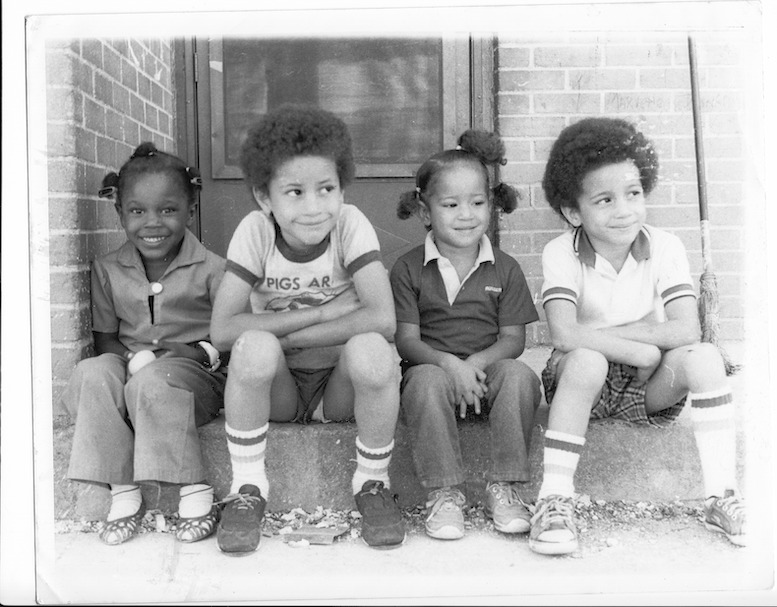

One of my all-time favorite pictures I took for my high school photography class later featured in an exhibit at my medical school in Galveston entitled, “All God’s Children.”

Demetric’s youngest sister and her cousins