Dear Dr. Wible,

After a surgeon killed himself at my husband’s office, his group hired a physician to replace him and a few weeks ago he also killed himself—at his desk at the hospital. I feel his suicide is being swept under the rug. I can no longer remain silent.

As the spouse of a dedicated and honorable surgeon, I witness countless atrocities buried under “the greater good.” In training, we’re told “things will be better.” You will be an attending! You will be more respected. You won’t have to work nights. You’ll have expensive things, pleasurable hobbies, time for family and friends. In short, IT WILL ALL BE WORTH IT. Truth is—working conditions are worse.

Being a physician’s spouse is like being a single parent. My husband is on his 33rd straight day of call today. If we are lucky, he’ll makes it to our kid’s school performances—once every few years!

All that life sacrificed on the altar of getting to where you are. Gone. All those times you could not be there for your spouse or your kids. Gone. All those gatherings you missed and then were criticized by unsympathetic family members. Gone. By the time our husbands realize their dreams have died, they’ve lost multiple colleagues to suicide. We all know our spouse might be next. As surgeons’ wives we already refer to each other as surgeons’ widows.

Let’s be honest, most practices are not run on an altruistic basis. It’s about the bottom line and covering your ass in the event you are sued—with no emphasis on mental health—until one of your partners puts a gun in his mouth and blows his head off at work.

In the wake of such a tragedy we have group meetings, and someone says, “we need to give each other hugs and go to therapy.” Does it happen? Maybe. For a hot minute. Then it’s back to the daily grind and making sure your billing sheets are turned in every morning. No more talk of mental health. Counseling isn’t even covered on our insurance plan!

Daily trauma that doctors witness is pushed aside—left to fester until someone snaps. Sadly this isn’t limited to physicians, but also impacts their children (who have higher rates of suicide too). Our surgeon who died last week lost his son to suicide a few years ago. Yet another reason wellness MUST be a priority for everyone—not something hospital admin claim to care about and have very little tolerance for.

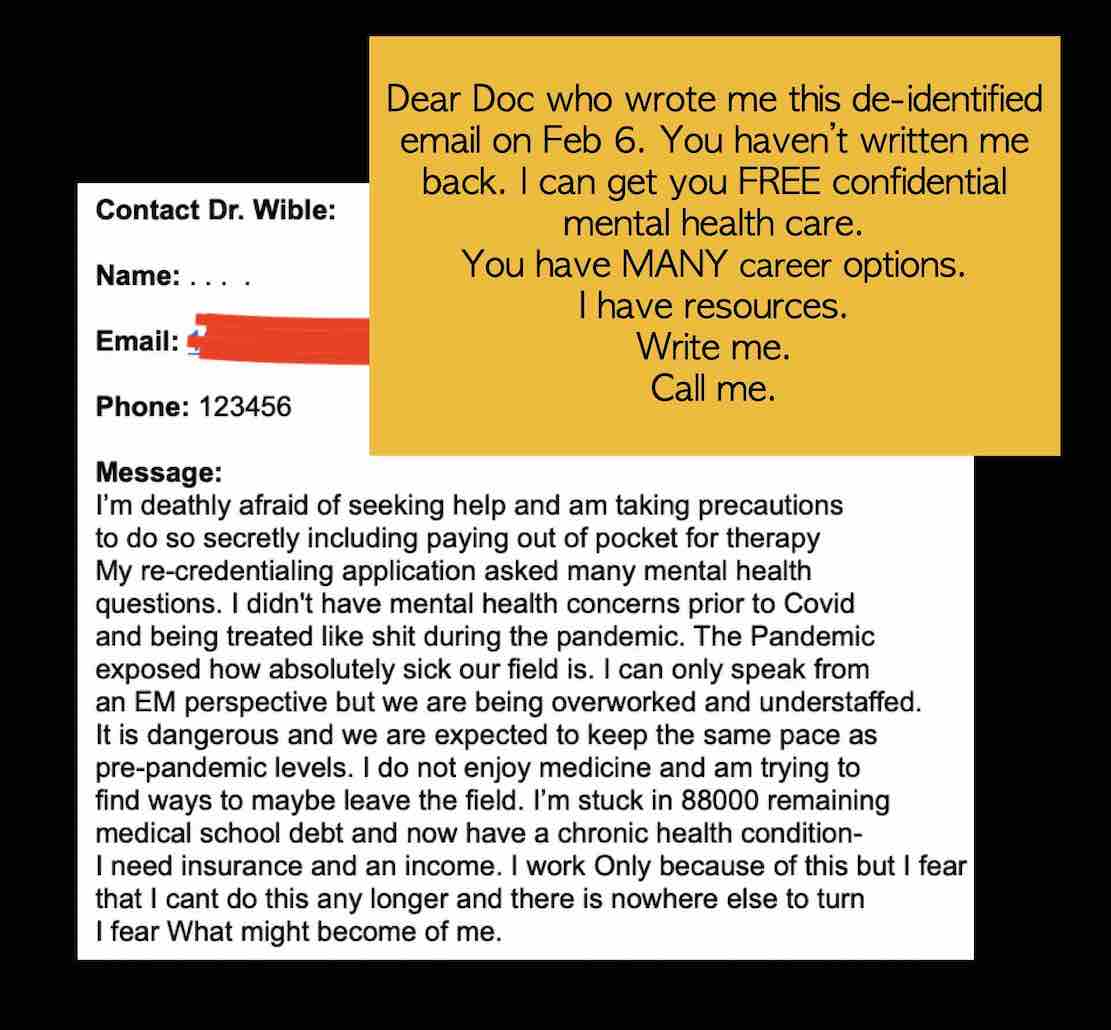

We all know it’s taboo for physicians to discuss being emotionally spent and at the end of their mental/physical rope. God forbid your competency be questioned and your medical license be jeopardized. With god-like standards to uphold, doctors are expected to give 110%. That’s not human, nor humane. When overworked physicians get home, they’re checked out—nearly catatonic. Wives fear bringing up even little things as it may light a fuse that sets off our husbands. We even have a Facebook group for physicians’ wives experiencing domestic violence!

One thing is for certain—more doctors will die by suicide. I pray my husband isn’t next.

May THAT truth motivate action: Tell the voice in your head that claims you need to live up to societal expectations of what a physician should be to shut the hell up. (I’m talking to women docs too). Life if short and then you die. Society won’t care. Your spouse and family will miss you. We already do!

Lastly, see a freaking therapist. You can afford it. Make time in your schedule. Take a deep breath and clear your mind for two minutes. Set your phone alarm (even if you think it seems ridiculous, come on, just 120 seconds—please, try it this week!). Yes, I know you have to see 56 patients in clinic today. Yes, I know people’s lives depend on you. However, your patient’s life depends on you being alive. Caring for your mental and physical well-being is PART OF YOUR JOB!

~ Surgeon’s “Widow”

* * *

Dear Surgeon’s “Widow,”

Thank you for your courage! Sharing your truth is the prerequisite for healing. I agree all physicians require non-punitive, confidential, and proactive mental health care. Waiting until passive suicidal thoughts become actions is not the right plan. Upon interviewing male physician who survived suicide attempts, I’m told once they “snap,” they take definitive action within 3 – 5 minutes. We’re unlikely to save our doctors in the last minutes of their lives.

What works is creating a culture of wellness so doctors feel safe at work—appreciated by colleagues and patients. Even a short text message has averted a surgeon’s suicide. Patient thank-you cards have prevented physician suicides. We need kindness.

To prevent future suicides, we must investigate each doctor suicide.

A targeted treatment plan, requires an accurate diagnosis. What type of suicides are we dealing with—and why? Most suicides are solitary and private. A double suicide is when two people die by suicide, often simultaneously. A suicide pact is an agreement between two or more people to kill themselves. Suicide contagion is when one suicide increases the likelihood of other suicides soon afterward and can lead to a suicide cluster when three or more suicides occur in short order at a rate greater than expected within a community. None of these terms accurately describe what happened at your husband’s practice.

We have no terminology for the phenomenon of occupational suicide of a physician who replaces another physician who has died by suicide. On my registry of nearly 2,000 doctor suicides, I know of several cases in which very similar physicians die within less than two years in the same institution (even on the same spot). Example: Two J1/H1-Visa Muslim physicians from Mauritius die by stepping off the same NYC hospital building. Why? No investigation has been launched. Two Jewish orthopaedic surgeons from the same practice die by gunshot wound. I’ve spoken with a suicidal Jewish anesthesiology resident who inherited his pager from a prior Jewish anesthesiologist who died by suicide at the same hospital. One common theme in these scenarios is a toxic workplace rife with bullying and overwork that leads to loss of multiple physician lives. In my quest for a precise name for this phenomenon, some physicians have suggested these cases are occupational homicides due to human rights violations.

To stop the loss of life, we must diagnose the problem and treat what appears to be a systemic issue claiming individual lives with no end in sight. More doctors will die unless we have the courage (like you) to speak out and define the real occupational culprit.

~ Pamela L. Wible, M.D.

P.S. The Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) protects workers from being killed or harmed at work. The physician work environment is clearly in violation of the OSHA. High-hazard industries such as hospitals and clinics with more than 10 employees must record work-related injuries that require more than first aid on an OSHA form and post a summary of their yearlong injury log in a place where workers can view it. You have the right to request full copies of the report from your employer. Within 8 hours after an employee death due to a work-related incident, employers must report the fatality to OSHA. When medical institutions fail to report physician death by overwork within 8 hours—as required by OSHA—it is a breach of institutional integrity, an active cover up, and an obstruction of justice. The law requires employers to provide employees with working conditions free of known dangers. If unsafe, unhealthful, or hazardous: (a) file an OSHA complaint; (b) request the latest yearlong OSHA injury report to ensure your employer has reported all workplace deaths, and; (c) request a NIOSH evaluation.

Author’s anonymity is upheld per her request. For physician trauma recovery support groups, monthly retreats, (including physician widow retreats) & free physician suicide helpline, contact Dr. Wible here.

Pandemic Healing (4 pm EST) ~ Get help for long haul, job loss, death of family, peers. (1 hr).

Pandemic Healing (4 pm EST) ~ Get help for long haul, job loss, death of family, peers. (1 hr).