Attention: Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division

My name is Pamela Wible, M.D. I’m a family physician in Oregon. I believe I’ve suffered Title II ADA violations by multiple medical boards.

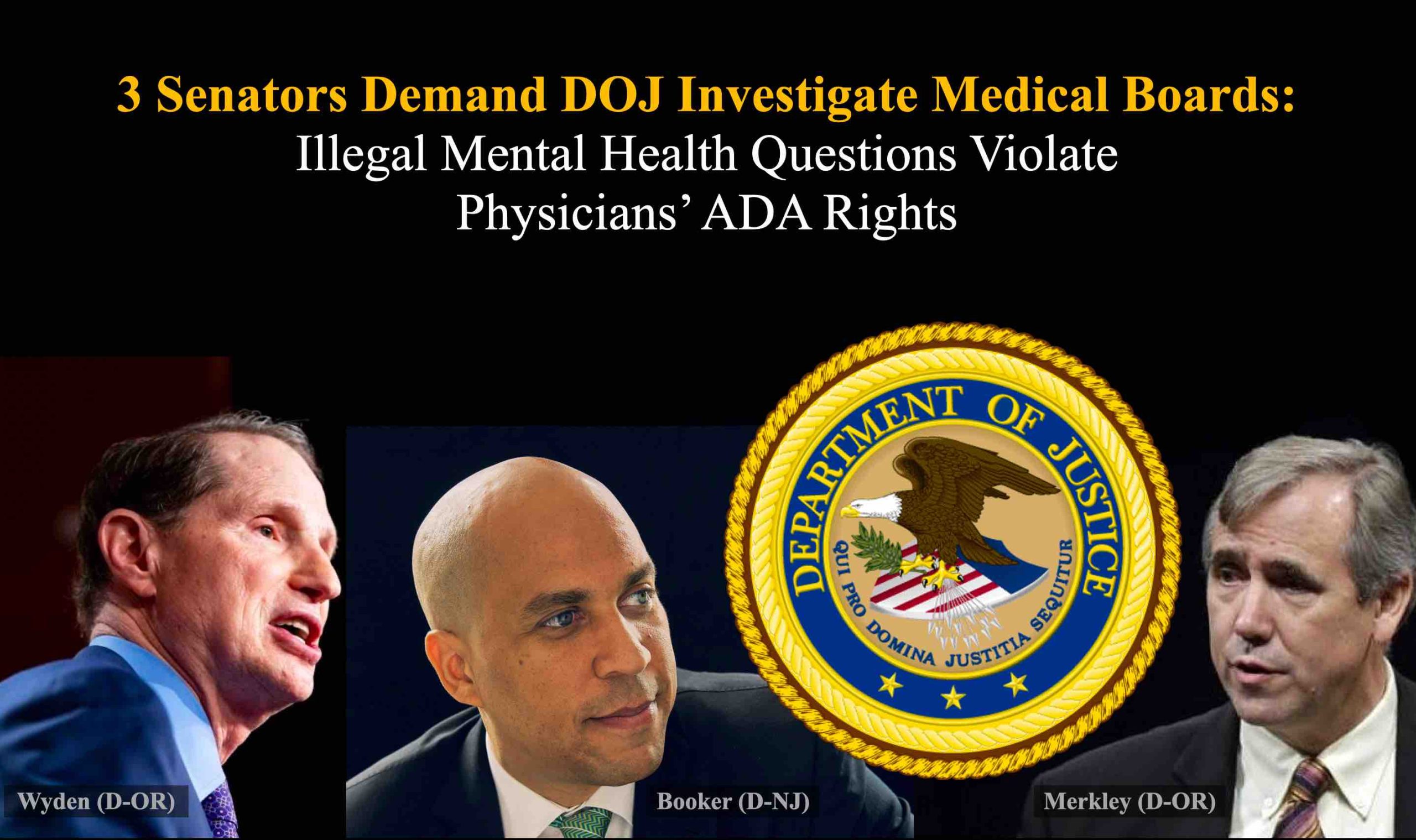

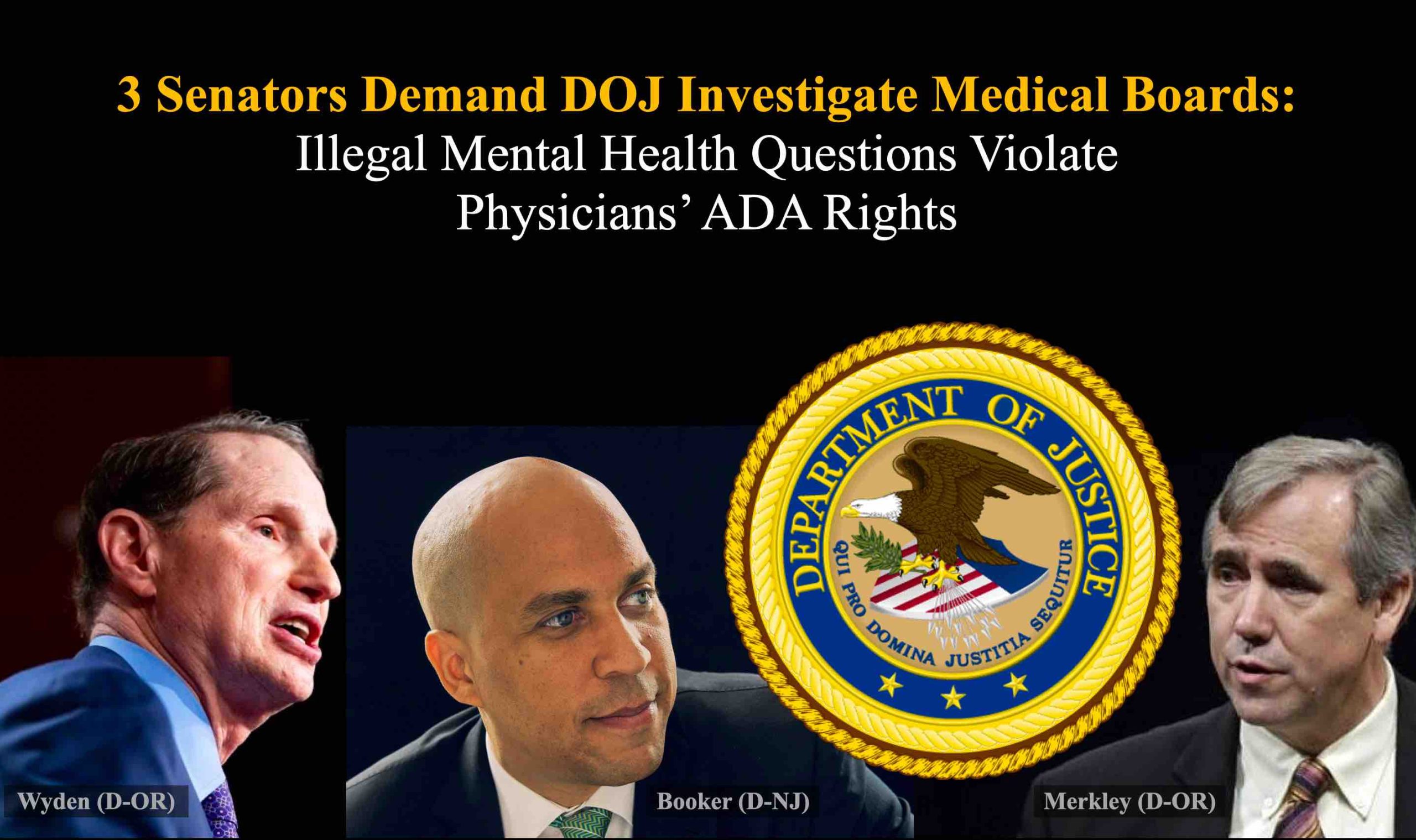

In my 2019 study (1), I revealed how competent physician applicants who disclosed mental health conditions suffered discrimination and career jeopardy by medical boards nationwide. Senator Wyden cited my study in his 2023 letter to DOJ (2), demanding federal investigation of medical boards’ unlawful practices.

During my 30-year career, I’ve cared for patients in Texas, Arizona, Washington, and Oregon. Each state’s licensure application included ADA-impermissible mental health questions (1) unrelated to current competence—an unethical and illegal breach of privacy, confidentiality, and non-discrimination principles.

Falsifying answers to these impermissible questions risks license denial, and in some states, is a crime. Applications have threatened hefty fines—and even jail time.

Answering YES to these questions requires defending oneself in writing (in person at board request), risking costly unwarranted examinations by board-appointed non-impartial evaluators, and license delay or denial in each state, leading to similar actions in other states.

As a competent, qualified physician, I’ve always answered NO to these questions—at great personal expense.

I’ve been forced to hide my pain. I’ve never sought care from a psychiatrist (or any doctor) for work-related anxiety and depression.

Like my peers, I’ve always put on a happy face at work. I’ve consistently denied my own needs. I’ve repeatedly delayed my own care. I’ve sought off-the-grid therapists who use paper charts—to safeguard records from board subpoena. I’ve acquired psych meds on my own—so as not to be tracked by pharmacies or boards.

As long as medical boards continue to harm doctors by violating our rights under the guise of “public safety,” I can’t trust my profession to keep me safe.

In 2012, after three doctors from my town died by suicide, I asked Oregon Medical Board to track doctor suicides. Their attorney declined. They seemed disinterested in doctor suicide data.

Alarmed, I launched a free doctor suicide helpline. I’ve spent ten years listening to suffering physicians. I can tell you definitively the most common complaint I hear is, “I’m afraid of career repercussions for seeking mental health care.”

I love caring for patients as a family doctor. Yet I retired early—to care for my physician peers.

How can we serve our patients when we are struggling in silence—even dying by suicide—amid state-sanctioned mental health discrimination and punishment by medical boards?

I implore the DOJ to protect all Americans—regardless of occupation—by removing ADA-impermissible mental health questions from state medical licensure applications. Physicians must be able to voluntarily seek confidential care when needed—not deny, delay, and self-medicate occupational wounds until they fall prey to regulatory agencies that force doctors into punitive so-called “physician health programs.”

Please contact me should you need additional data. I truly appreciate your commitment to upholding our nation’s laws for liberty and justice of all.

Respectfully,

Pamela Wible, M.D.

(2) Wyden, Ron, Booker, Cory, and Merkley, Jeffrey.

Congressional Letter to DOJ re State Medical Boards Violating ADA with Intrusive Mental Health Questions. February 23, 2023.

* * *

Do you fear mental health questions on board applications? Unwarranted scrutiny by board-selected psychiatric evaluators? Do you feel you must hide your emotional struggles? Avoiding or delaying seeking help? Enduring career-threatening discrimination for disclosing a mental health condition to your board? Been falsely flagged as impaired? Sent to a physician health program?

If you answered yes to any question above, your civil rights have been violated by a medical board. Please submit your DOJ ADA complaint here (you may remain anonymous).