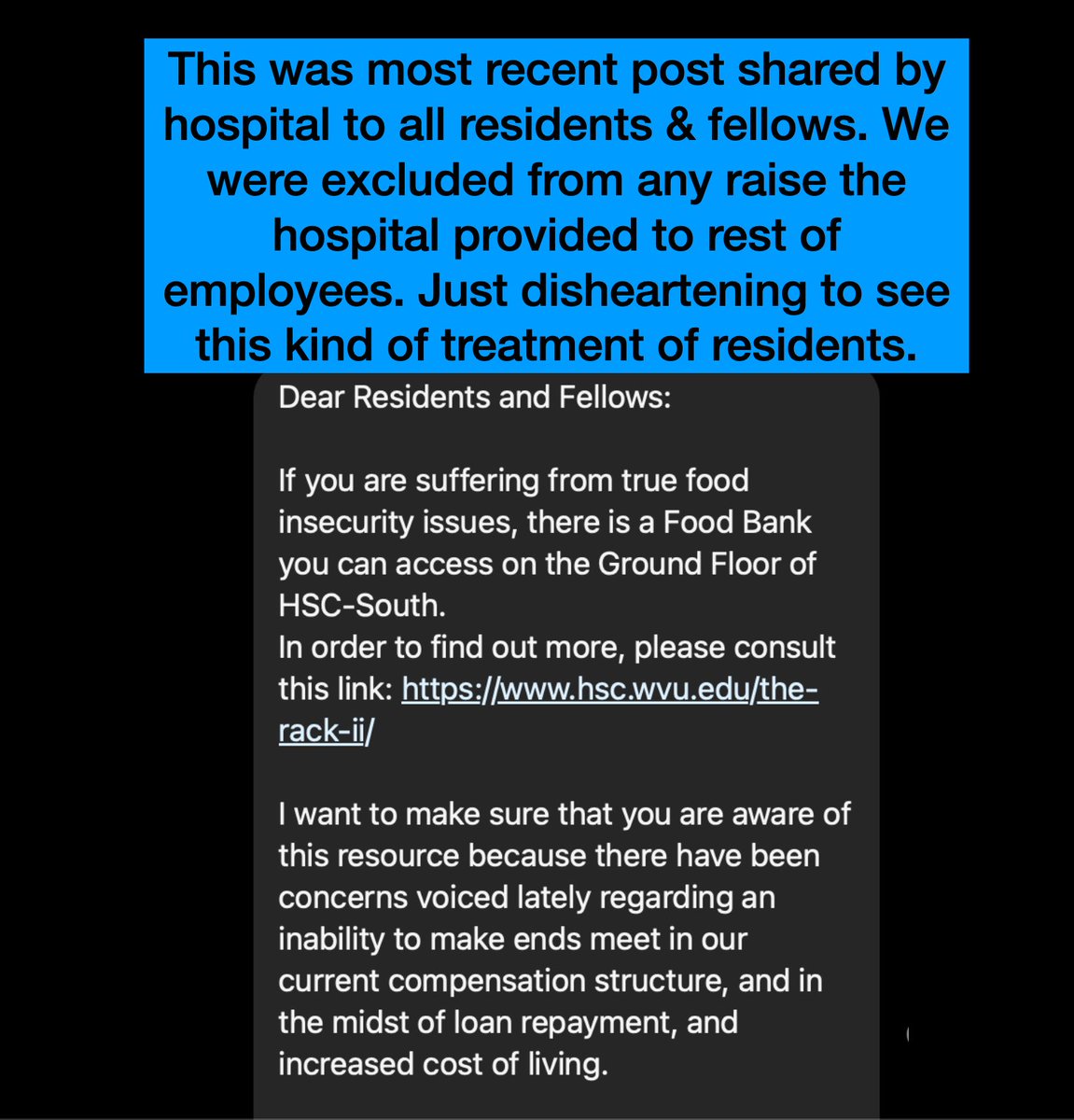

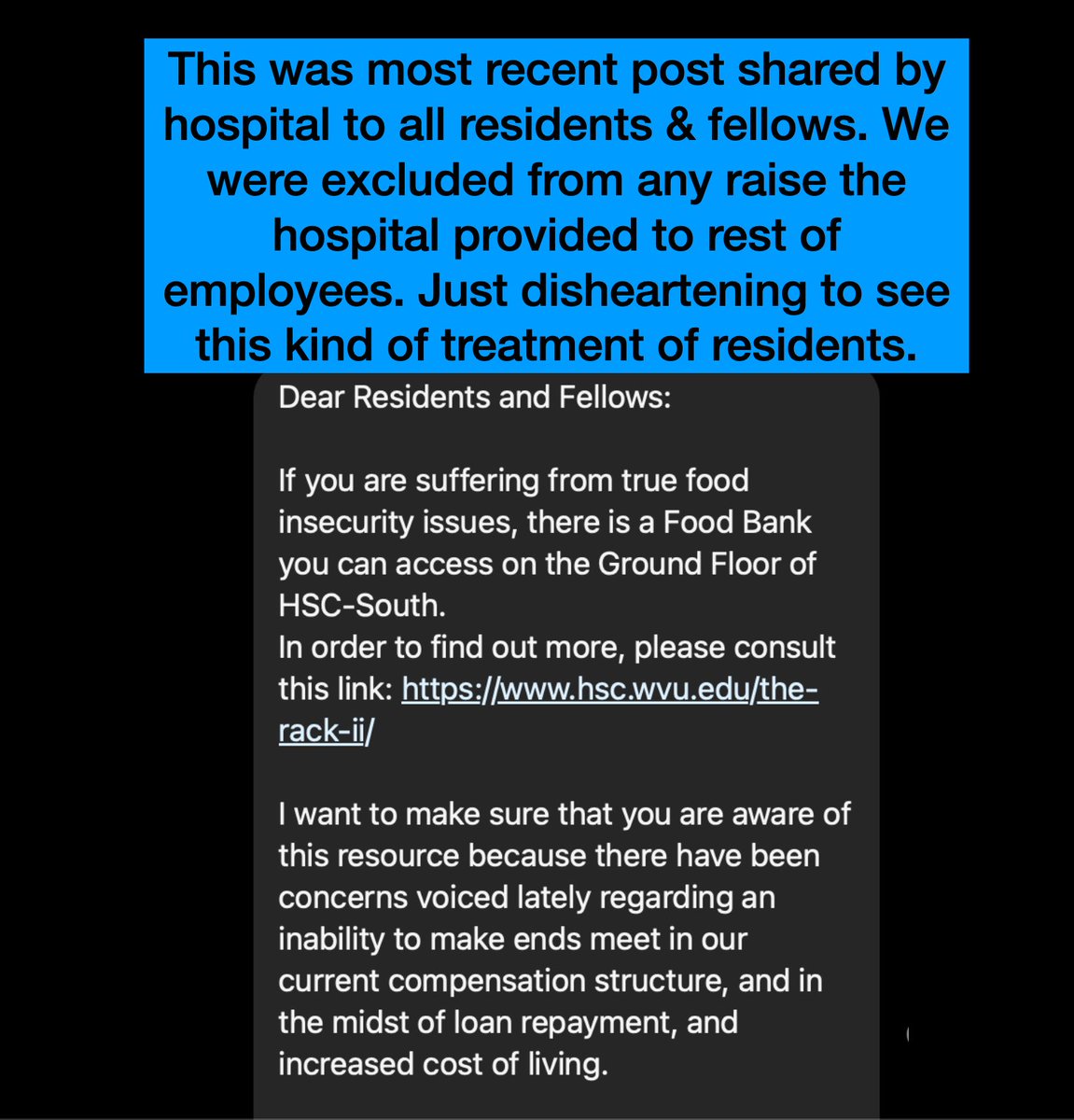

Just got this Instagram message (de-identified, posted with permission). A few comments:

“I calculated my own residency compensation as under 250 pennies per hour.”

“What the actual f***. Food bank??? Increase to a livable wage jeezz that’s embarrassing.”

“Average salary of residents and fellows is $60-80k depending on area and program. When working an 80+ hour work week it usually averages to less than $14 an hour. As a literal physician, my 16 year old brother makes more than I do at an Italian ice shop”

“I calculated for a friend recently that she started at 11 dollars per hour as an intern and is up to 15 per hour this year as a third year resident (min wage in her area is 16/hr so still below a livable wage for her in NYC area)”

“When I was a resident we had a meal card for food this is insane to work this hard and be hungry. They likely don’t even have time to visit a food bank.”

“Even residents in the military is making an actual income bc they are officers. This is insane.”

“The government gives them [hospitals] nearly 140k per resident to pay them 65 k this is bs.”

“I didn’t even finish clerkship because they expected us to work 55 hours per week in clinic while only receiving $10/DAY, and on top of that prepare for exams and ‘get a nanny.’”

“It’s not uncommon to see medical students and residents fainting from hypoglycemia and recovering on gurneys in the hallway.”

“Two times I fainted from hypoglycemia. The second time I hit my head on a stretcher on the way down and I was given juice by a kind nurse and then expected to keep seeing patients like nothing happened.”

“At my old residency, one resident went into diabetic ketoacidosis and required hospitalization for several days because of our irregular access to food and water.”

“Labor laws don’t apply to medical students, residents, or physicians. No bathroom breaks. No time for meals or snacks. Due to irregular access to food on shifts that exceed 24 hours, medical students and physicians, like most victims of starvation, develop pathologic behaviors around food including stealing apple juice and crackers from the nurses’ station or grabbing leftovers from patient trays.”

“I learned to eat fast. If you ever see someone eating fast they either served time in prison or medical residency!”

“Getting a break was sitting on the toilet doing your business while wolfing down anything!”

“The cafeteria closed at 1:00 pm so usually we’d miss breakfast because we’re on the wards at 7:00 am and breakfast is at 7:00. And then we’d often miss lunch because it is really hard to get off at 12:00 pm to go get something to eat,” reports a hospitalist on a multi-day shift. “And then the cafeteria was closed because it’s a small hospital so we’d have no access to food. And then I’d think, ‘Well, I’m gonna go out to get a Whataburger, (which I hate eating) and then I wouldn’t get out.’ When we’d ask, ‘Could we have access to food?’ Administration would respond, ‘Well, you outsiders, you come in and you tell us how you need to eat.’ It was insane.”

“I couldn’t afford to buy food at the hospital on an inpatient medicine rotation. I also was given no place to store anything so I would fill my pockets with dollar store granola bars and pray they kept my stomach from growling. One day I forgot them and got so hungry after a long day that I stole cold leftover rice from a meal for attendings in the physicians’ lounge. I was so afraid I would be caught and have to explain. I lost almost ten pounds off an already small frame during that one-month rotation.”

“Medical trainees lose significant weight due to lack of access to food. A close physician friend went from 130 down to 88 pounds during the first five months of her intern year.”

As a third-year medical student witnessing a surgery, I wasn’t doing anything too important other than holding a retractor with another classmate. Suddenly she collapsed onto the floor. She was out. Her blood sugar was 26.They checked my blood sugar. It was 24. I was still standing.”

* * *

Food deprivation is lack of access to food essential for normal function of the human body. The right to food is protected by Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Medical professionals know well the impact of food deprivation on the human body. When our physiologic needs for caloric input are unmet, we struggle to function.

Labor laws guarantee that employees get bathroom breaks and regular meals during their shifts. At PetSmart, my dog groomer gets two 15-minute paid breaks and one 30-minute unpaid break during her 8-hour shift. At Starbucks, my barista gets two 10-minute paid breaks and one 30-minute unpaid break per 8-hour shift. Both work 40-hour work weeks. Even my pilot gets breaks and can’t fly more than nine hours straight. Yet new doctors-in-training work 28 (or more) hours per shift without breaks, meals, or sleep and are expected to work 80 (or more) hours per week.

Labor laws don’t apply to medical students, residents, or physicians.

Many doctors work for less than minimum wage.

Now they are being sent to food banks to eat.

Your thoughts?

Some excerpts above from Food Deprivation chapter in Human Rights Violations in Medicine (a survival guide for residents).