Open Heart, Helping Hand:

A Eugene doctor ‘self-deploys’ to the Astrodome in the Wake of Katrina

By Pamela L. Wible, MD

For The Register-Guard

Published: September 18, 2005

Images of Third World chaos confronted us on television sets throughout the world in recent weeks. Victims of Hurricane Katrina, mostly African-American and impoverished, remained stranded in New Orleans and in small towns throughout the Gulf Coast. Seemingly paralyzed First World spectators sat with their eyes fixed to the TV. The suffering crowds in the New Orleans Superdome chanting “Help, help, help!” became vividly imprinted in my mind.

As a physician I was willing to help – though several official communications by email indicated I was not needed. Physicians were warned: “Do not self-deploy.” Though I received these warnings daily, I went with my conscience, my intuition that I was needed, and I “self-deployed” to the Houston Astrodome, where the victims were finally being bused after surviving hurricane, flood, starvation, dehydration and near-asphyxiation because of bureaucratic red tape delays and inefficiencies.

The Astrodome and surrounding buildings were prepared to accept up to 25,000 victims, and the impressive Astrodome health center was created overnight. The makeshift hospital/clinic in the Reliant Arena included more than 20 exam rooms, a pharmacy, radiology facilities, a lab, 24-hour observation capability, quarantine sleeping quarters, and specialty sections including pediatrics, orthopedics, social work, mental health and more.

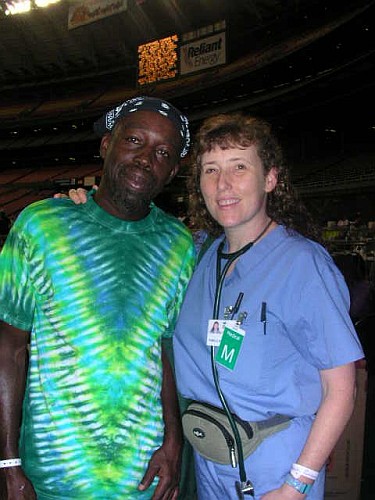

Staffed by the Harris County Hospital District, the local doctors and residents helped as they were able. Volunteer doctors and nurses from out of state were a welcome relief, and were placed on 12-hour shifts with the locals.

When the buses began to arrive, only one internal medicine doctor was available to perform triage. Bus after bus lined up, and though half the people were too faint to walk, they crawled off the buses so that others behind them could get out. Each person had a small plastic bag containing all his or her worldly possessions, covered in human waste along with the poisonous gumbo that now surrounded their beloved hometown. The stench was overpowering. Their skin – especially the babies’ skin – looked as if it had been dipped in hydrogen peroxide.

As patients were triaged to hospitals, others were rehydrated, fed and helped to small green cots that covered the Astrodome floor. Supplies were readily available, and the refugees soon left their tattered bags in a large pile at the entrance to the arena as they realized their basic needs would be met. Though barely alive and heartbroken from their tragedy, they were peaceful, kind and incredibly polite.

I spoke to the doctor who was the first to care for the refugees. With tears in his eyes, he recounted some of his experiences in those first few hours. A busload of dehydrated hospice patients arrived amidst the others; they had no medical records and had been without medication or food for days. He queried a gentleman about a curious severe sunburn limited to the very top of his head. The gentleman revealed that he stood for two days, packed so tightly with others on a small dry piece of land that a deceased man beside him was unable to fall.

Then there was a couple caring for 22 children during the storm because their apartment was considered the safest in the area. The couple then witnessed the destruction of surrounding homes and the deaths of the children’s parents. Floodwaters forced the couple to place the newly orphaned children on large pieces of furniture. Then two inflatable swimming pools were used to float away to higher ground.

In the corner of our makeshift hospital, I pulled back the yellow plastic curtain with a taped piece of paper indicating Room 9. There I met a sweet, 57-year-old woman I’ll call Beulah. Beulah was covered in a rash. As she scratched her limbs viciously, she related the horrors of her past week.

Beulah, a piano teacher from New Orleans’ Edgewood neighborhood, raised 102 foster children over 18 years and was caring for two boys, one mentally retarded and the other autistic, when Katrina hit. Initially relieved by the light damage, she then noted the rising floodwaters after the levees ruptured. She and the boys were forced to the second floor as she watched her beautiful organ and piano submerge, along with a lifetime of photos and memorabilia.

Her neighbors screamed for hours and then stopped. Had they drowned? Later, as she hitched a ride on a small boat out of a second-story window with her two boys, she noted a deceased neighbor being tied to her home to preserve her identity. Beulah and her boys were soon deposited on a dry patch of Interstate 10 and told to wait with others for rescue buses.

She witnessed countless horrors as she remained at this freeway bus stop without food or water for two days. A man arrived after losing his entire family, climbed the overpass and jumped to his death in front of the “rescued” crowd. He lay face down, floating in the now-bloody waters surrounding his head as nightfall enveloped the eerie scene. People were screaming and others were having seizures as Beulah tried to help and tried to find a safe spot for her family to rest.

A woman arrived the next day with a small baby wrapped in a blanket. When Beulah went to peek at the baby, the mother warned her not to wake him. Beulah paused and became tearful as she told me the baby was as blue as my scrubs. She was eventually able to tell a passing police officer, who took the baby from the shrieking woman and drove them both away. Their safe, dry patch of Interstate 10 was surrounded by the unbearable odor of sewage, death and suffering.

She told of the arrival of the buses, the transport to the Astrodome and the kindness of the people who have cared for her in Houston. “The last time I got this rash was when my mother passed; it’s my nerves,” she said.

Despite her traumas, Beulah had a beautiful smile and was incredibly polite and appreciative during our time together. I was amazed by her resilience. It was easy to treat her rash and her insomnia, and to replenish her diabetic supplies. Though it was more difficult, I was honored to hold her hands tenderly and allow her to begin the process of grieving over a tragedy.

I remember a famous French Quarter musician in Room 8. He was to meet with other musicians for a hurricane party the night of the storm. Sudden chest pain sent him to the emergency room instead. After a diagnosis of gastric reflux, he was discharged, but was unable to leave because of the rising water. The ER moved to higher ground and eventually he was evacuated to the Astrodome with no possessions – his CDs and all his music lost. He was here now to be evaluated for his diarrhea and to see if he needed to be quarantined. He also needed basic medical care for glaucoma and diabetes. With his Guinness Book of World Records toenails, I suggested podiatry as well.

I saw many skin infections, chemical burns, diarrhea and injuries. Some patients required admission for infected joints or pneumonia. Identifying chronic medications was challenging, because medical records and pill bottles had been swept away. Most were on something for “sugar” and “pressure.”

I noticed the prescriptions from the Astrodome pharmacy all had “Prescriber: Katrina, Hurricane” printed on the bottles. Can’t say I have ever seen anything like that before!

Despite the high rate of diabetes, there was always a large box of Krispy Kreme doughnuts on the diabetic supply table beside the glucometers. Comfort foods, I suspect.

I met many heroes. Glen Beverly, an apartment manager of the St. Peter Claver Apartments, single-handedly floated to safety all his tenants on a Winn Dixie freezer door. I discovered creativity and strength in the face of disaster. I saw bravery, courage and, most impressive, the resilient, fun-loving and open spirit of the survivors who worked collectively to save one another, placing the needs of others in front of their own.

At the Astrodome health center, I served as family physician, social worker, orderly and friend. When not caring for the patients, I was comforting the survivors from cot to cot on the Astrodome floor, passing out handmade soap, aromatherapy lotion, angel wings, lavender eye pillows and gifts from my hometown – including money from a benefit garage sale on my street.

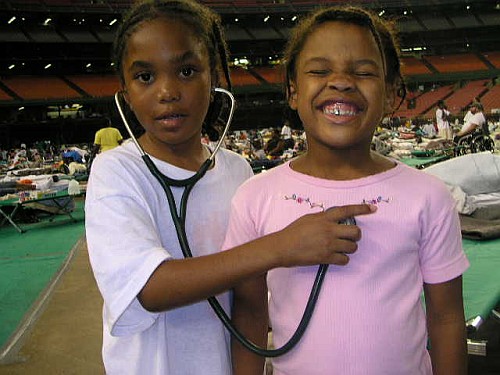

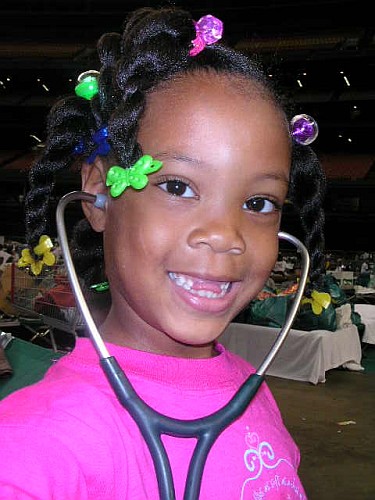

The children were curious and playful, checking out my stethoscope and listening to each others’ hearts. I came to share my skill, to offer an open heart and a helping hand.

For me, it was a simple case of self-deploy or self-deplore. Leaving the comfort of the known and jumping in to help was the least I could do.

Our leaders should disentangle themselves from their red tape and come out of their large offices and do the same.

Pamela L. Wible, MD is a board-certified family physician in Eugene, Oregon.

She opened the Family & Community Medical Clinic on April 1, 2005.