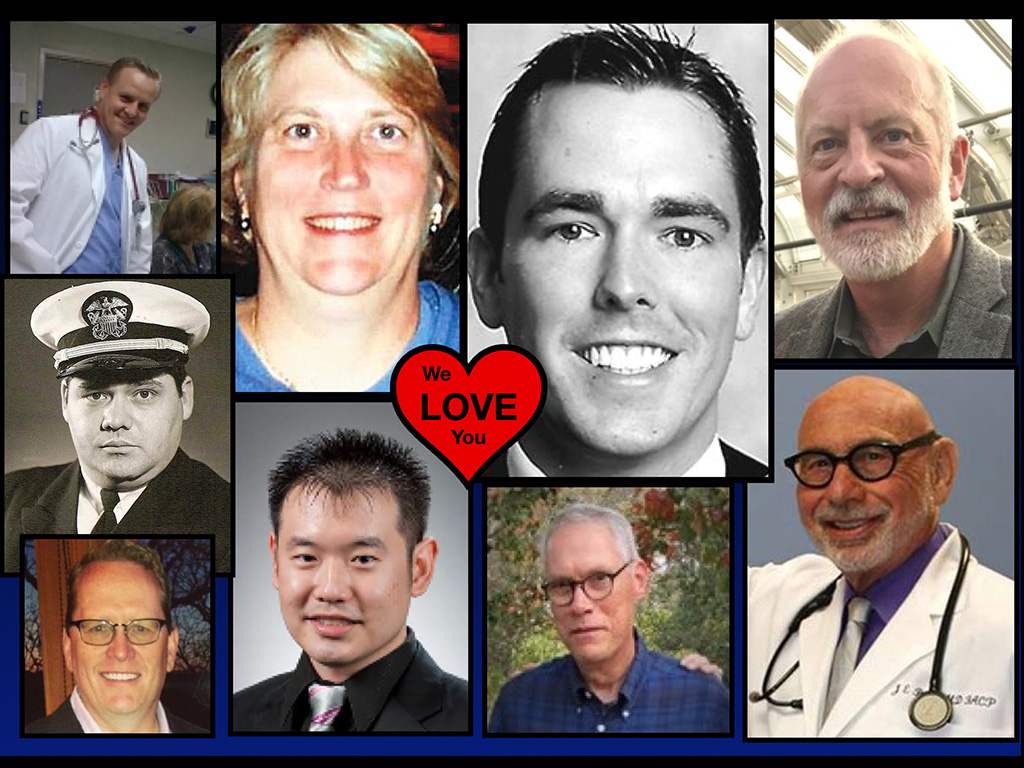

Dedicated to the lives of Oklahoma physicians we have lost to suicide

On January 11, 2019, I delivered this talk to the medical students at Oklahoma State University Health Sciences to a surprise standing ovation and again the following day as the Oklahoma Osteopathic Association keynote address. Audio/transcript below. (Video will be posted when available).

Dr. Jonathan Bushman: Next, we’d like to welcome our keynote speaker. Dr. Pamela Wible, M.D., is a family physician born into a family of physicians, who warned her not to pursue medicine. She soon discovered why. To heal her patients, she first had to heal her profession. Fed up with assembly-line medicine, Dr. Wible held town hall meetings, where she invited citizens to design their own ideal clinic. Open since 2005, Dr. Wible’s community clinic has inspired Americans to create ideal clinics in hospitals nationwide. Her innovative model is now taught in medical schools and featured in Harvard School of Public Health’s newest edition of Renegotiating Healthcare, a textbook examining major trends with potential to change the dynamics of healthcare. Dr. Wible speaks widely on healthcare delivery and is the best selling author of Pet Goats & Pap Smears and Physician Suicide Letters—Answered.

When not treating patients, Dr. Wible devotes herself to medical student and physician suicide prevention. She’s investigated more than 1,100 doctor suicides, and her extensive database and suicide registry reveals highest risk specialties—and solutions. In between treating her own patients, Dr. Wible runs a free doctor suicide hotline and has helped countless medical students and physicians heal from anxiety, depression, PTSD, and suicidal thoughts—so they can enjoy practicing medicine. Please help me welcome Dr. Pamela Wible.

Dr. Pamela Wible: I’m so excited to be here. I loved the last talk. We have a new DPC patient over here, the AV guy Mike is so excited to sign up. He was really influenced by that talk by Kyle. And so today I’m going to talk about how I survived my own suicidal crisis, our opioid national crisis, and a gazillion patients begging me for marijuana—to finally love my life as a doctor.

I knew I was screwed when this hippie guy with dreadlocks came to my house while I was gardening. This guy accosted me in my own garden at my home looking for pot. And I was totally confused, out of context. Then he tells me, “I heard you’re the cool doctor in town.” So he thought that I was going to give him medical marijuana by coming to my house. And then I had another patient show up. This is in Eugene, Oregon. I don’t live in Oklahoma. Another patient brought this giant pot plant on the city bus coming to his appointment with me and was hoping to trade or barter or whatever like this is his payment. I had to explain, “No, I don’t take pot. Just cash or check.”

So this is a situation in Oregon. We have a state where we were the first to decriminalize marijuana in 1973. And in 1998 we legalized medical cannabis and then recreational cannabis in 2014. And of course you know, in Oklahoma, you legalized it in 2018. So I’m like 20 years ahead of you on the influx of patients demanding pot from me. By the way, I went to med school in Texas—UTMB/Galveston. And I did not go to medical school to be running a medical marijuana mill.

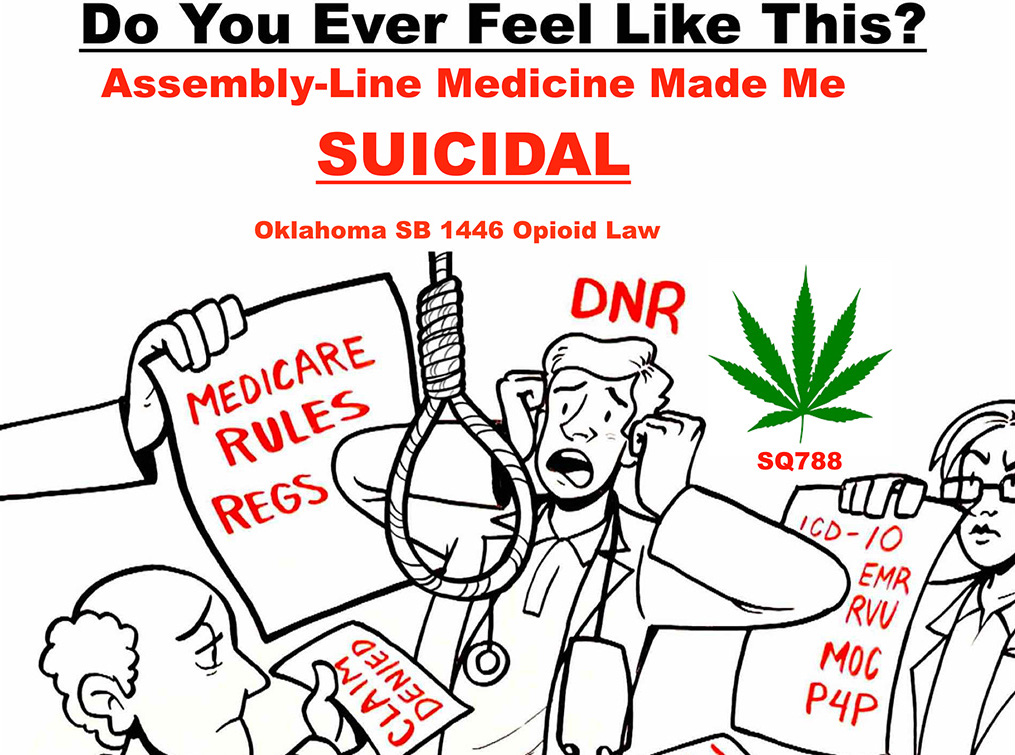

Ever feel like this? In a situation where everyone is making demands on you to fill out paperwork and get people onto disability. And now they want pot from you. Is this really the best use of my education and my skills? It doesn’t make any sense. Assembly-line medicine—which is what I call this production-driven model that most docs are in—made me suicidal. My job sucked.

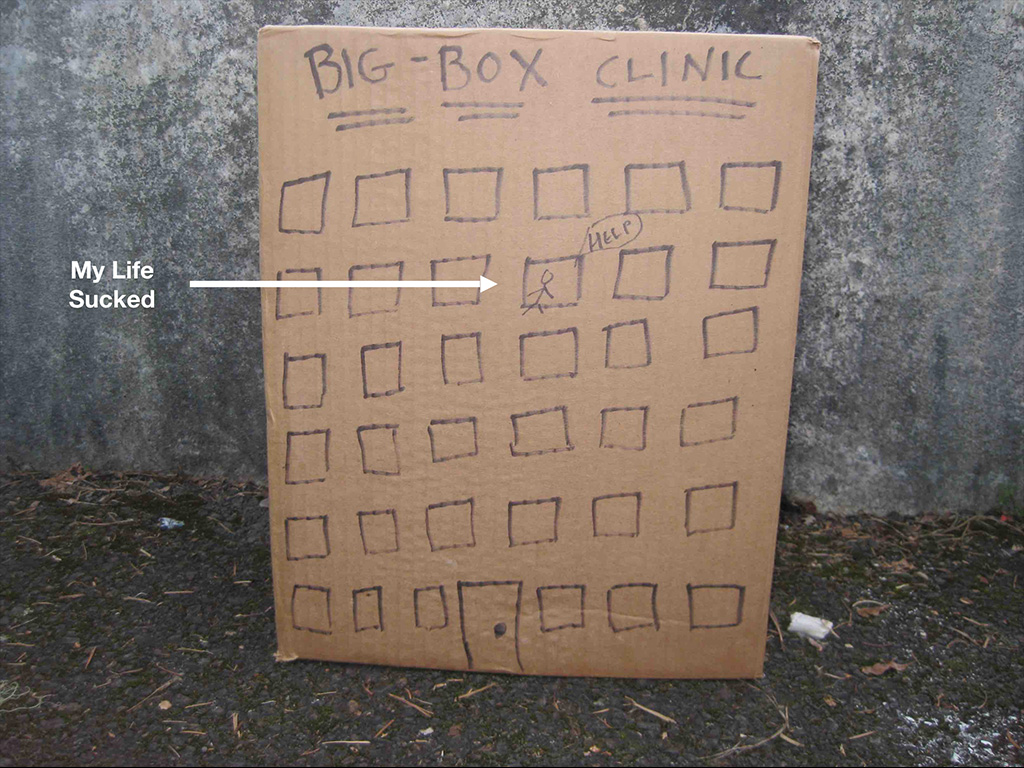

So this was my situation. You can see that’s me there screaming for help. This is art therapy for the captive physician in a big-box clinic. I felt trapped and unable to utilize the skill set that I had to help people in seven-minute increments with an embezzling clinic manager. It was insane, double-booked patients. My life sucked. I’m sure you can relate to what I’m saying. I had to do something different.

So I did something really crazy. I just decided, hey, if I’m not happy, and the patients aren’t happy, I’m just going to put the patients in charge. I don’t know how to run a clinic. I tried six jobs in 10 years. They all sucked. They were all assembly-line, big-box clinics. I’m just going to ask my patients. You guys design a clinic. Write my job decision. I’ll work for you. I’ve had enough. So I held a series of nine town hall meetings over a period of six weeks in Lane County, Oregon. And I collected 100 pages of written testimony. I pretty much told people, “Hey, I’m going to do whatever you want, as long as it’s basically legal.” And so I was able to adopt 90% of what people in my county needed for ideal healthcare and opened our clinic in less than one month with no outside funding.

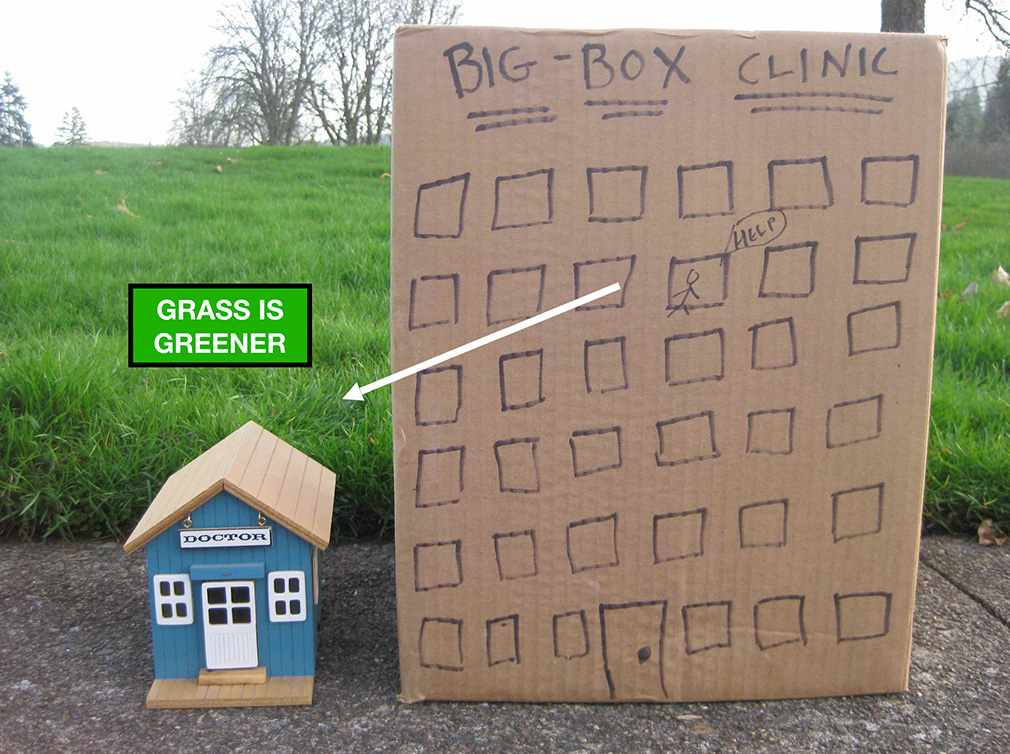

Here’s a picture of going from big box to where the grass is greener. The grass is greener when you’re in your own clinic, and you own it, and you’re in charge.

I launched for $627.50 and I’ll explain how I did that because some people are concerned about startup costs for this sort of thing. They can be really low: quarterly insurance payments for malpractice were billed four times a year, so that was about 350 bucks upfront. And then my rent for my little one-room, cute, little office in a wellness center was $280 a month. This was 14 years ago. It’s gone up to about 400, but that’s not a big deal. And then I spent 40 bucks on some Goodwill chairs, and that was it. My exam table had not arrived yet by the time my first patient came, but he didn’t care if I examined him on the floor. We were having a great time, because we were back into the real patient relationship. And so I just want people to know, you can actually launch your clinic.

I have not set an alarm clock for work in 14 years, because I don’t want to be woken up by loud noises. After med school, I can’t stand loud noises jolting me out of sleep. I believe in following my circadian rhythm, and I am my best around 3:00 PM in the afternoon. This is kind of early for me to be on stage. I don’t generally set an alarm because I usually go to sleep around 3:00 in the morning, wake up around noon, go to work around 3:00 PM. I’ll stay there as long my patients need. And I work Monday, Wednesday, Friday afternoons and evenings, because I don’t believe working two days in a row is healthy, not for me at least. So like to spend one day in between the days I work. And then I’m at my best with patients. It’s so fun, and I make more now than I made before, back when I gave 70% of my income away to the infrastructure that I didn’t need to run my clinic. All this infrastructure has grown up around you, and it’s a lot of people. You’re paying their salaries and everything. You don’t need them. If you’re doing lung transplants, you need a team, and you need a helipad, and you need all that stuff. If you’re doing primary care, outpatient specialty care, too many cooks in the kitchen, get rid of everyone. It’s called disintermediation, by the way, which is a term I learned in the self-publishing industry, which means removing the middlemen.

That’s the actual thing. That’s the cure for most of our ails. As physicians we need to disintermediate our lives—get rid of all the people that have no business between us and our patients. And I just want to forewarn you that some people, when they do this, they inadvertently recreate the big-box clinic in a smaller box. Don’t do that, because then that’s another nightmare. Now you own that big thing in a small box, and it’s going to drive you nuts. You’ve got to use a different business model. You’ve got to use a different kind of thinking to do this.

Medicine is an apprenticeship profession and sadly we’ve lost our mentors, which is why we’re all adrift together, wondering what to do. We’re getting our mentors back like Kyle and Jonathan and the wonderful people we have here launching new, innovative models (that are really just the old model coming back DPC and relationship-driven medicine). So when you do that, when you have the right mentors, you don’t replicate what’s not working. And since we’re creatures of habit, we inadvertently start replicating what we’re used to, even though we’re in a smaller box. So don’t do that. Follow a new model, and the grass is definitely greener. Now I’m doing house calls again! SO awesome!

Here’s a picture of me actually doing a house call in Oregon on the Pacific Coast for a patient of mine who used to drive 100 miles to see me. He has terrible arthritis. He can’t drive anymore, so whenever I go up the coast of Oregon, I always go visit him and do a almost unannounced house call and hang out with him for a while. Here we are.

He’s such a cool guy. Love this dude. Here we are doing an office visit over the Pacific Ocean. Is that awesome? Sitting on a little wicker loveseat. He’s adorable. I just love this dude. And by the way, he’s sort of a poor guy. He used to be the gardener for this particular property. And the woman who owns it is letting him live in that house for free for the rest of his life, which is awesome. And so he’s really got a good deal between me as his house call doctor, rent-free house over the Pacific Ocean, this guy has it made.

There I am filling out paperwork for his medical marijuana, because he feels better on medical marijuana for his terrible arthritis. So I have a few patients on it, but I’m not running a mill. And this is not what I want to be doing all day long. And I’m also filling out his paperwork for his disabled fishing permit. There’s a special series of pages you have to fill out if somebody is disabled, and they want to continue hunting and fishing. So you get a license for somebody to hunt and fish with you to help you, if you can’t hold the rod on your own and all that jazz. So that’s what I’m doing.

Here I am in my office. I threw a surprise party for my friend. Long story, she thought she was coming for a physical. She went in the back room to get undressed, and everyone jumped out of the bathroom. I live in a small town.

When you’re in a small town, you know everyone, and they’re your patients, because where else are they going to go? So I have a lot of fun at work. And by the way, I might seem kind of out to lunch, West Coast hippie type, yet I’m really a very conservative doctor. I’m totally by the book. I just like to have fun. Some people call me the female version of Patch Adams. I’m really fun, okay? So I just want to have fun at work. I believe you can accomplish just as much with a smile and a party hat, and you can put Mardi Gras beads on your patient during a physical. And you could laugh the whole time and have as much fun as you want and still deliver great medical care, and leave your patients laughing.

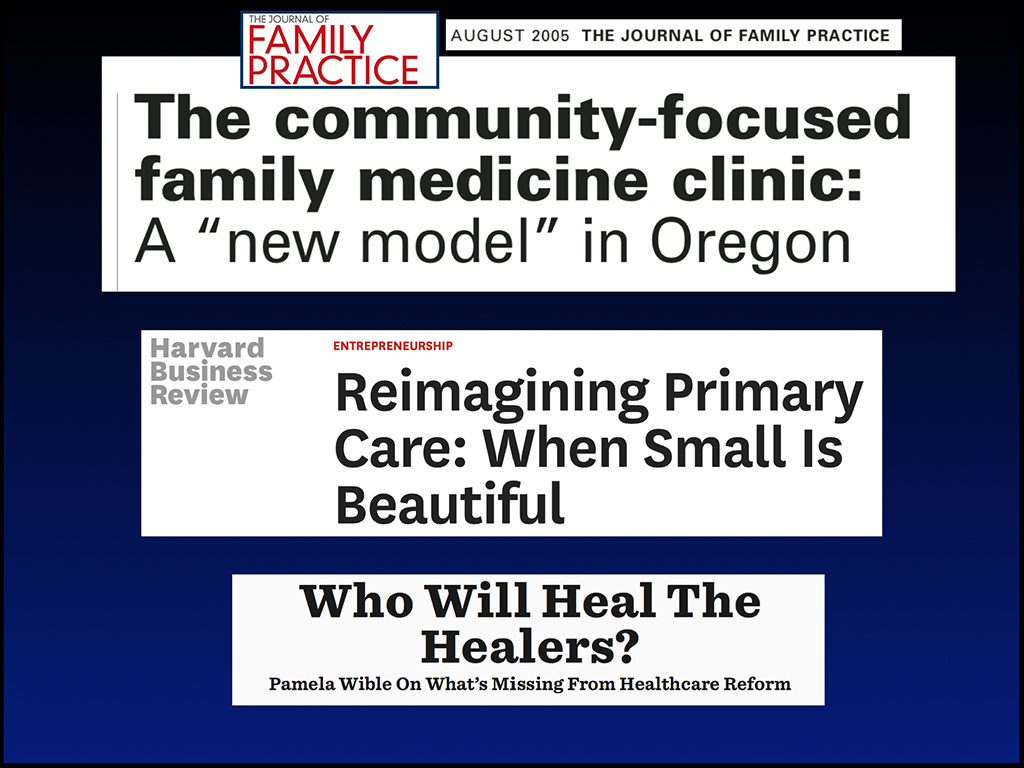

As a result, our community-designed clinic caught some national attention. Four months into it I had an article in the Journal of Family Practice on this new community design model. First one in the country where patients design their own medical clinic. I learned a lot from that, and now it was even in the Harvard Business Review. And then this is other article came out: “Who Will Heal the Healers?” Interesting title that was very prophetic.

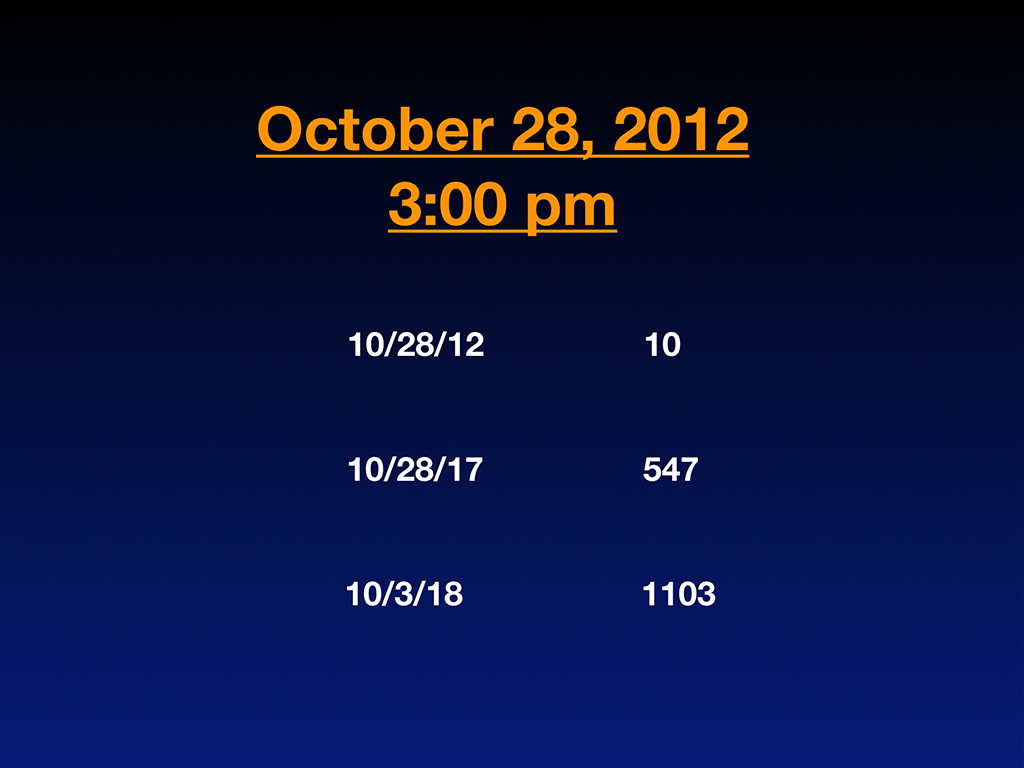

Then my entire life changed on October 28th, 2012 at 3:00 PM, when I ended up in the second row of a memorial service for the third physician we lost in my town to suicide. And these aren’t fringe guys. They’re all male, top of their career and just suddenly gone. And so I’m sitting at his memorial service, and I’m noticing that of course everyone, small town, knows what happened. He shot himself in the head in a public park in he middle of the day, this pediatrician in my town. Everyone knows at the memorial how he died, but nobody will say it out loud. Everyone is whispering “Why?” in the bathroom. Everyone wants to know why he shot himself in the head in the middle of the day in a public park, which is a very pubic suicide. But nobody will ask the question out loud. How odd—especially for physicians. As scientists, we should be interested in this topic, because aren’t we here for healthcare? Isn’t it about decreasing pain and suffering? And these are our own brothers and sisters who are dying by suicide. Yet even physicians won’t say this out loud. They’re sweeping it away as if it didn’t happen—a perfect scenario for creating a situation in which there’s repeat occurrences, if you don’t identify what the problem is.

I was fascinated by people’s reaction to the suicide and the hush-up nature of it. And I couldn’t stop thinking about it, because I’m a scientist, and I’m a curious human being on the planet, plus my job is being a doctor. My job is solving medical problems, so I wanted to know just to answer the question for myself why this guy died. And not just this guy, I want to know why the other two guys died in my town in just over a year. Three guys died in my town of suicide, all doctors. And sitting at the memorial, I started counting how many people that I knew had died by suicide as physicians. I was in my early 40s and I knew 10. Can you believe that? I was shocked, including the fact that, by the way, two of those guys were men that I dated in medical school that died by suicide—not while they were dating me. This is when they decided to marry other women. That’s just the truth of the matter.

Okay, so I started tracking these. I started a little list in my little diary. I kept a doctor suicide diary, and kept writing down names. Then I wrote a little blog about it. Five years later, I end up with 547 names on this registry. This was just a hobby of mine I was doing outside of clinic. But it took over my life, because six years later, just the end of last year, I had over 1,100 names on this list. I’m just a private citizen interested in answering a question. And I end up with this massive registry of physicians from all over the country and world.

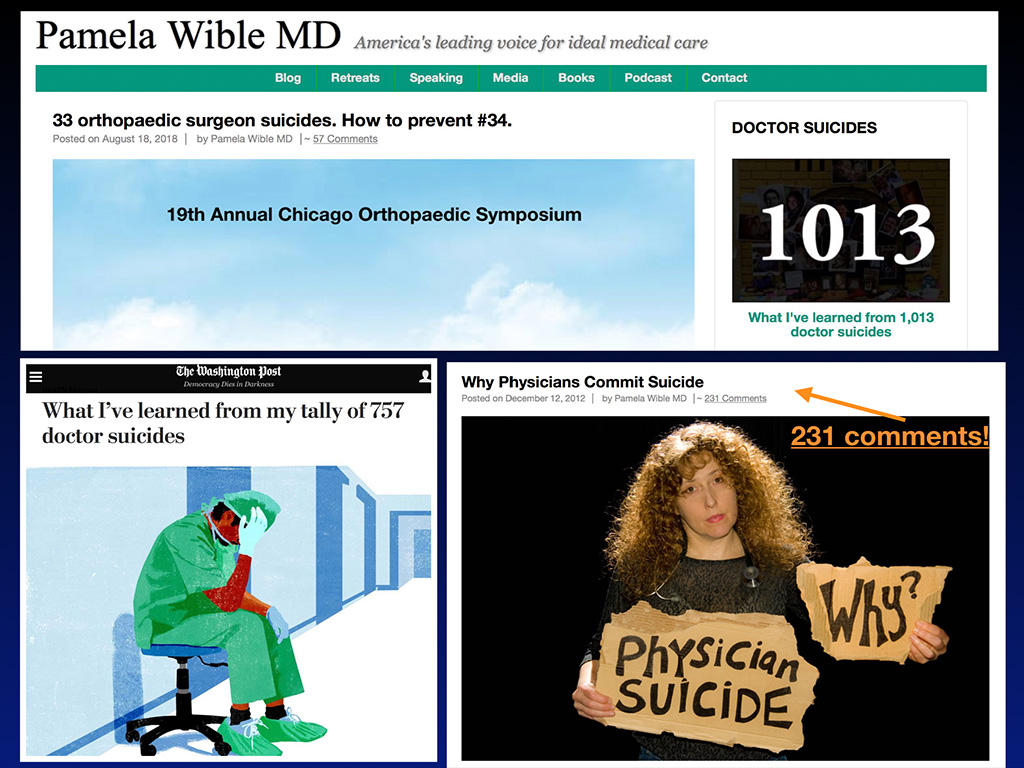

So I had a blog, by the way, for about a year before I was at that memorial service. And I don’t think anyone was reading it. I don’t think anyone cared how happy I was as a doctor. I had little photo essays of my house calls. It was cute and all that, but nobody really cared. But I started writing about suicide, and all of a sudden that blog there on the bottom got 231 comments. You think nobody is reading your stuff, and all of a sudden you get hundreds of comments. And some of the comments were people writing, “My son died in residency to suicide, and here’s his name. And here’s his situation.” They’re not only commenting. They’re telling me the entire case histories of their own children that died in medical school. They have classmates that died in residency, and patients are writing in about their doctors who died, but nobody did anything about helping them grieve from losing their doctors.

And then some of my blogs, kind of cool, started getting picked up by the Washington Post. The editor wrote me and said, “Do you mind if we republish your very well-written blog?” And I’m like wow. I didn’t really do that well in English in high school, but if I’m getting my blogs picked up by major newspapers, then go for it. So my physician suicide blogs have been picked up and run on the front page of the health science section in the print version of the Washington Post and online. Is that cool or what? And it just kept going from there. I ended up on Dr. Oz last year. So I think this is a topic that people are finally ready to discuss.

This is an actual wall in my house (in my home business office) covered with pictures of doctors and medical students who died by suicide. Many of them, I’m very close to their families, because—let’s just face it—in the aftermath of a suicide, often the person who’s died by suicide is shunned. So they almost get buried twice. They’re shunned in the aftermath of their death. And then the family, nobody wants to really talk about this with the family for too long. So a lot of times when I contact the families, they’re relieved that finally somebody is calling and wanting to talk about their loved one. Family members feel shunned and isolated, they lose friends. So much pressure to keep it quiet. And so hard to grieve in isolation. It’s just a nightmare.

So I started running these retreats for physicians. And last year in December, there were two women who lost their husbands to suicide as physicians. And one of them, by the way, shot both of his children on his way out. And so I’m recognizing the extent of this problem. By the way, I truly believe if that guy was a real estate agent, those kids would still be alive, and so would he. And they’d be rolling Easter eggs at Easter and doing family things. It’s our profession that has killed these people. And we cannot allow this to continue. And so I just was like, who’s helping these families that are left behind? And so I just out of the blue, because I was so good at these retreats with physicians, I decided to offer an all-expense paid trip for these widows. Where are they going to go? To the emergency room and cry? She lost her whole family. So I flew both of these women out. They both lost their husbands to suicide within a few weeks of each other. And they were high-profile cases that were in the news, and people kept contacting me, saying, “You should talk to them. You should talk to them.” Well I think they’re going to need more than a phone call and prayers for recovery and Bible quotes. I think they actually need more intervention than that, when their whole family is gone.

So they arrived in Oregon for a retreat, put them in a room together, so they could heal with each other, and did therapy with them with a therapist for three days in a row, helped them grieve the loss. One of them still had two kids, and the other one didn’t have anything. And they became friends. They were of course having nightmares, unable to sleep, so you want to put them in a room together, because they were afraid to sleep alone. Just some of the stuff that I’m doing, that really I had no idea I was going to end up doing this when I moved to my cute, little clinic and discovered this doctor suicide crisis.

But the joy of all this is when you’re in your own clinic, and you’re not paying 74% overhead, is what I was paying … Would you move to a state with 74% income tax? Because that’s what you’re doing when you work in those big-box clinics. You are giving it away to all these people. You know what? They could care less whether you live or die. They may not even care if your patients live or die. All they care about is how much revenue you can generate per millisecond. And I’m not embellishing this. Just the facts. You know what I mean? So I think the sooner we can recognize the reality of what’s going on, because we’re nice guys, we’re a little naive, do-gooders. But we’ve had people that are not such do-gooders bossing us around. When the A students are being bossed around by C students, that’s not a good scenario, got to break out of that.

So I just personally can’t stand the idea of losing any more of these people. That’s the situation I’m in, and so I just want to catch you up to speed. I’ve been running a suicide hotline for six years with doctors. I think I have gathered more information about this than probably anyone on the planet, including the ACGME and other people that think they’re protecting us with all their things they are doing (while they take weekends off and work 9:00 to 5:00).

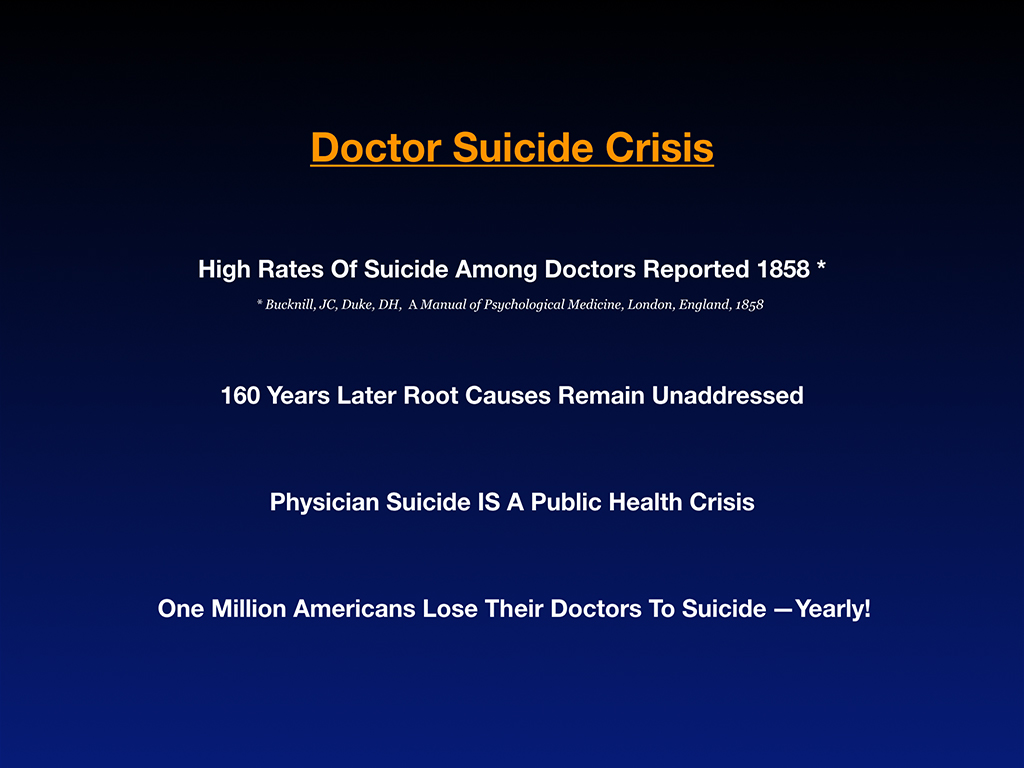

So anyway, the high rate of suicide among doctors has been reported as far back as 1858. In England was the first time it was recognized. Is that depressing, that 160 years later, we’ve done nothing about it? And this is our own problem of our own profession. And we’re talking to patients about seat belts and don’t smoke and don’t eat high-fructose corn syrup. We’re worried about everyone else, but meanwhile our partner just hung himself in the other room, and we’re like, can’t talk about that. That’s a taboo topic.

If we treated diabetes like this, whispering in the bathrooms about blood sugars we wouldn’t get very far with our diabetics. And so we have to talk about this, and I’ll make it fun and inspiring to talk about it because I’m going to give you some hope and answers.

Physician suicide is a public health crisis. It needs to be dealt with like a public health crisis, because more than a million Americans are losing their doctors to suicide every year. Do the math. Researchers believe that about 400 docs are being lost per year, but it’s probably more, because guess who fills out the death certificates. Unlike other professions, we’re covering for our colleagues even in the aftermath of their suicides. We’re writing it as an accident to preserve their reputation, even though it was … the gun went off. They think it was an accident, whatever we like to say, try to sweep it under the rug, so they get their life insurance payout, and we don’t piss off their wife or husband. So it’s like dancing around this in circles isn’t really helping.

When we have a public health crisis, we have to treat it like a public health crisis. Bird flu, Ebola, and other crises—people in hazmat suits, exact body counts, collecting the data. It isn’t up to what the family wants to do in the aftermath of a suicide when it’s a public health crisis. That’s when you’re counting the bodies, whether the family wants you to count them or not. They can’t say it’s a car accident or a heart attack when it was really a suicide, because we have a million Americans losing their doctors to suicide every year. So though I do believe, of course, being sensitive to the family in the aftermath is important, they don’t get to dictate how we deal with a public health crisis.

The suicide crisis will continue until we address it like scientists. I’m just passionate. I hope I’m not offending anyone. I have a lot of passion for this topic. And so this is every year—here’s the math: there’s about 400 doctors. That’s not even including medical students that die, because patients consider medical students their doctors. They don’t sometimes know the difference between short, medium and long coats, so they just think that’s the doctor. And so basically when you do the math, you’ve got … Let’s just say 500, if you include the medical students. So that’s 500 times the average, and maybe it’s different with medical students. They have less of a patient panel, but for family medicine, it’s 2,300 patients per panel in this sick system. Most of these doctors are probably dying in the assembly-line system and not in DPC clinics (where they’re jumping for joy and have time to attend their children’s ballerina recitals). And so that’s a million people losing their doctors. Okay, that’s a problem.

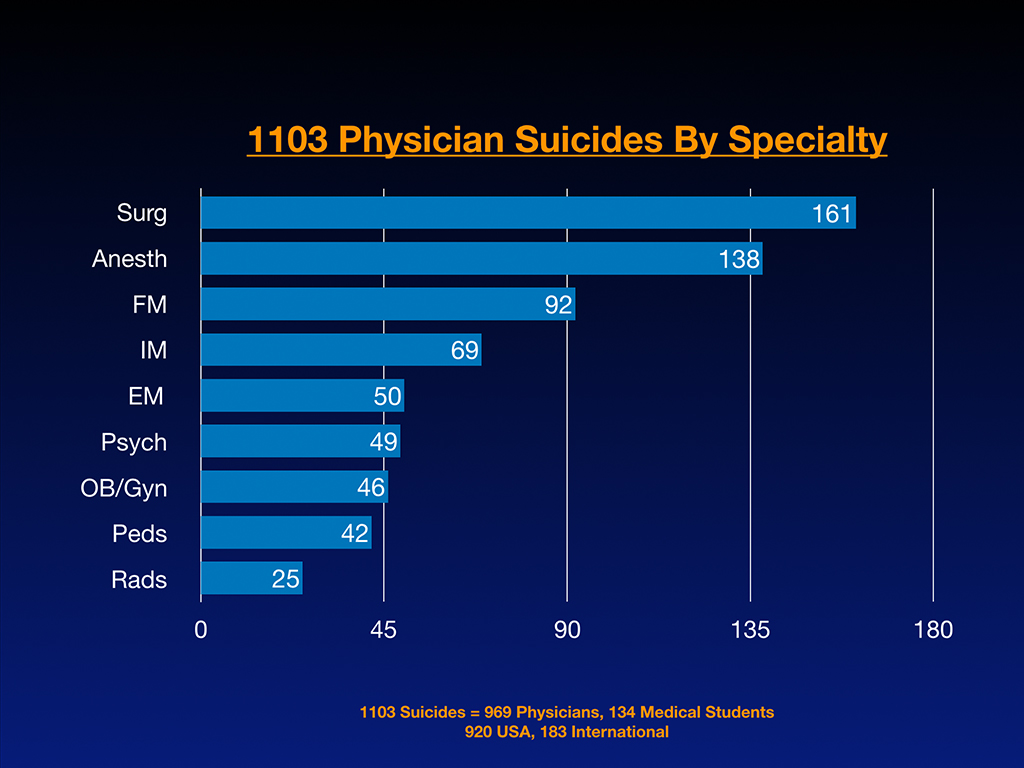

And this is by specialty. I did a little data analysis to get the linear thinkers excited so you don’t just think I’m drifting around on anecdotes. Here we go. This is raw data. There’s a lot of surgeons coming in, anesthesiologists. You can see this is the list of the raw numbers by specialty. Out of the 1,103 suicides that I’ve got on this list, 969 are physicians. 134 are medical students. 920 come from the US, and 183 are international. I’d like to clarify that I didn’t go out looking for any of these. These cases are submitted by people who contacted me to make sure their friend or family member was on the registry (and please note that nearly 100 of these suicide victims are honored in the new documentary—Do No Harm: Exposing the Hippocratic Hoax).

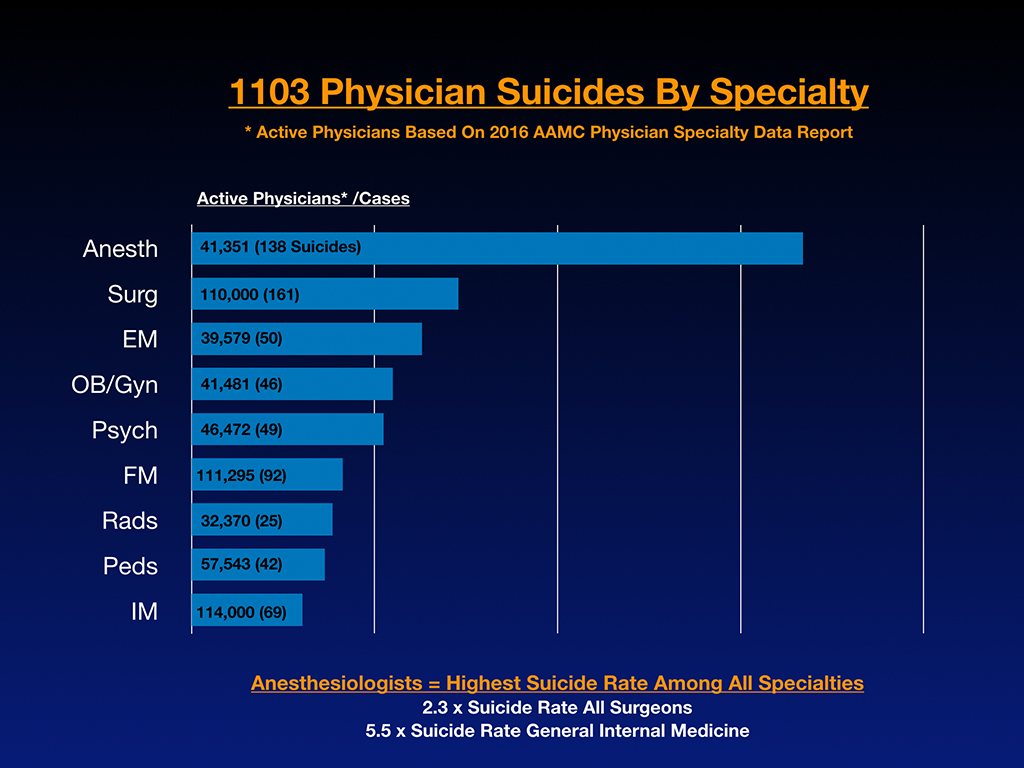

Sometimes after one of these suicides, I’ll get five or six emails within hours to days of the death. Even more important than this slide above is the next slide where I compare the numbers per active doctors in each specialty to determine risk per specialty, you can see anesthesiologists are through the roof. Based on these 1,103 cases, anesthesiologists are dying 2.3 times the number of surgeons and 5.5 times the suicide rate of general internal medicine.

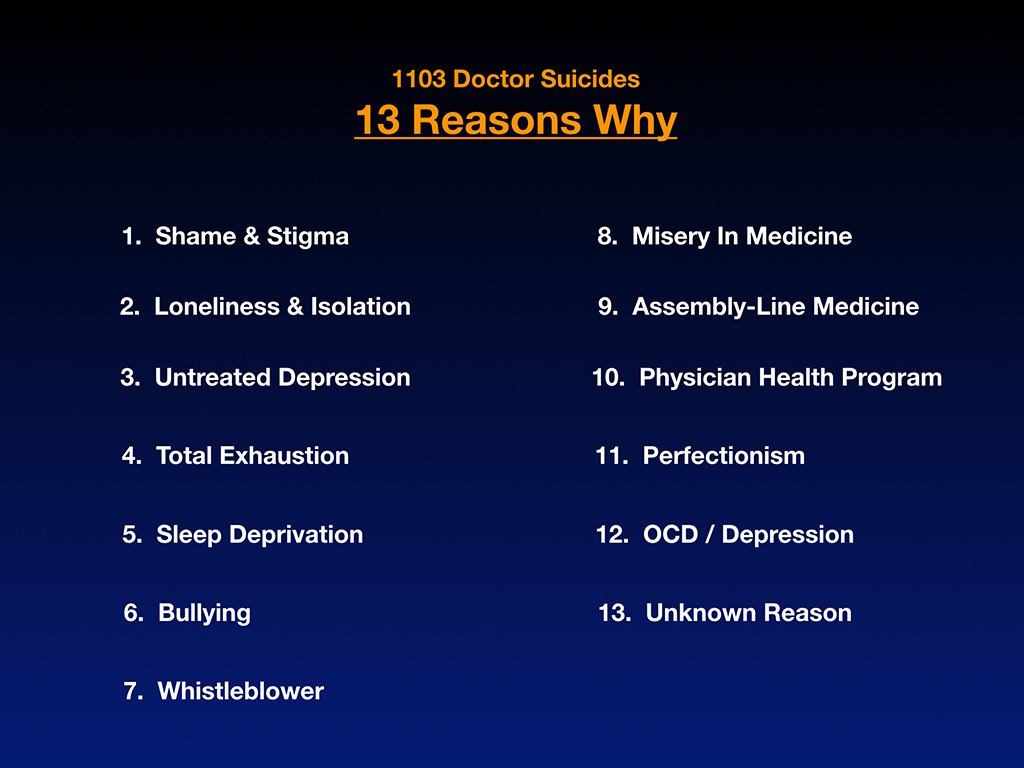

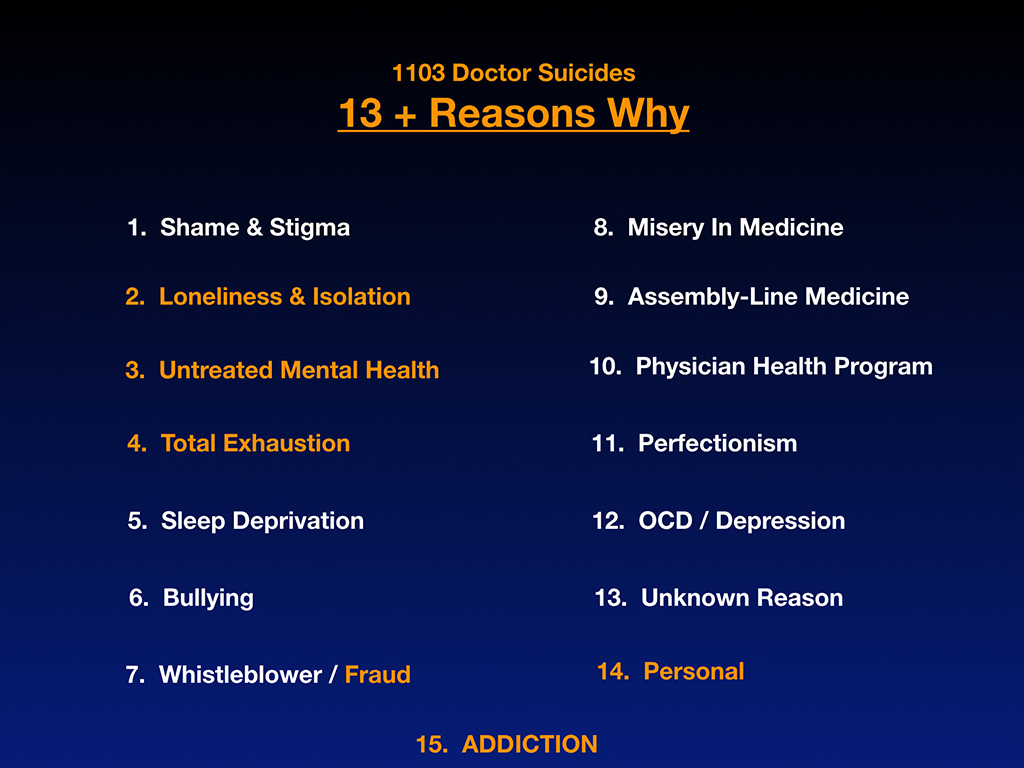

Okay, so this is a problem, and I’m going to discuss now the 13 reasons why this is happening with case studies of actual people, who I am close to their families. Most of them I feel like I’ve been adopted to their family, because I’m the one of the few who is still talking about their dead loved one. Like five years later I’m still calling and checking on the mom and still into it. I guess it’s taken over my life. I gave up mosaic artwork. I gave up knitting. I used to crochet. I just feel like this is going to be a better hobby for me and better potential benefit to the planet. So that’s why I’m doing this.

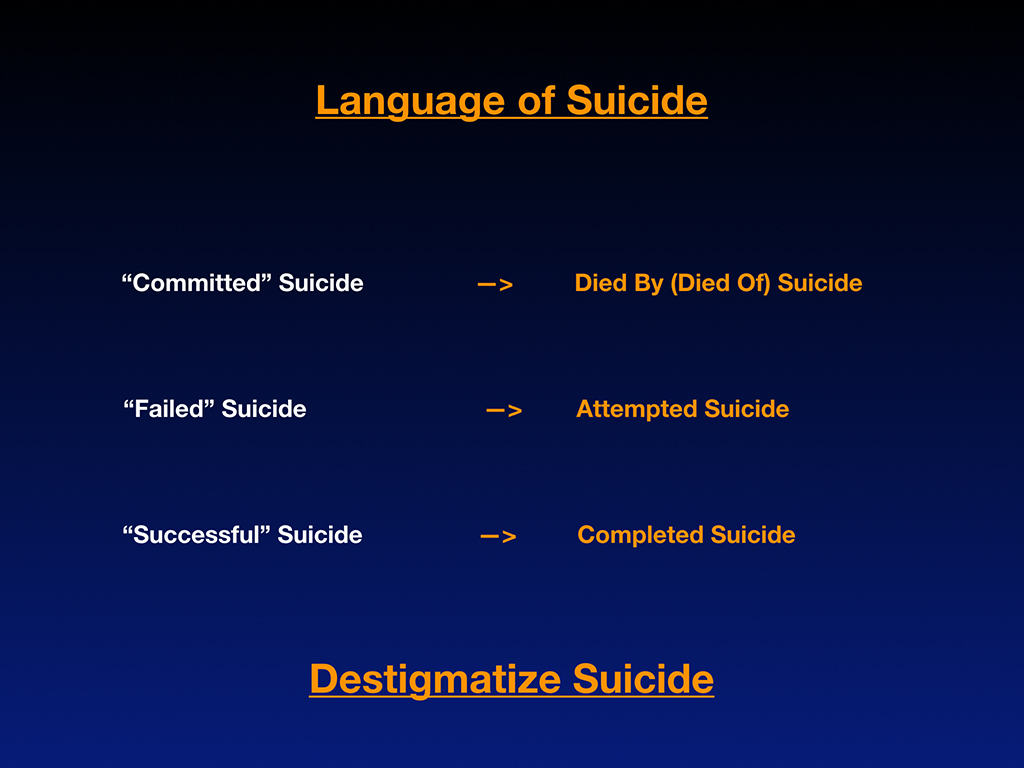

But before I start I’d like for us to give up the stigmatizing language around suicide. Because suicide is still a taboo topic, we don’t even know the right language to use. So we’re running in circles. We don’t know the right words to say. I’m just going to make it really easy. Don’t say committed suicide. That sounds like a crime, like burglary, murder and rape. These people were suffering a mental health condition, hopelessness generated by our profession. And so what you call it is like anything else, die by or die of pneumonia, heart attack, suicide. Let’s stick to the facts, and let’s not stigmatize the people with our language after they die. And so a failed suicide, this is totally perverted here. That means that you survived your suicide. That’s ridiculous. Why is that a failure? It’s attempted suicide, and then a successful suicide, how is that success? That’s not success. We just lost another doctor. Completed suicide, if we could just stick with the facts, I think we’d be able to collect the data with less emotional overlay and trouble communicating with each other. And so just a plea to de-stigmatize suicide. And so I’m going to share some actual case studies.

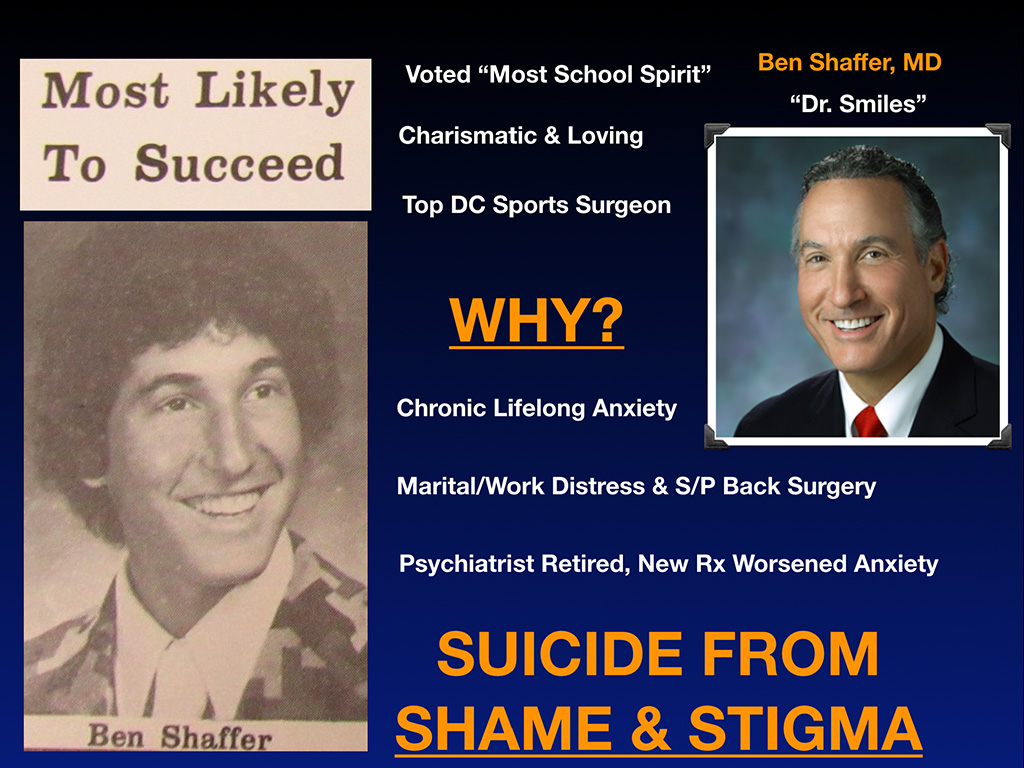

Now this guy is awesome. I love him. His name is Dr. Benjamin Shafffer, and he is the totally coolest orthopedic surgeon. In seventh grade, middle school or whatever, he was voted most school spirit. He’s charismatic and loving. If you can’t tell this guy is frigging awesome, he was the top DC sports surgeon. And I don’t know how people do it. I never was into OB and stuff like that. My attending told me it’s “hours of boredom for minutes of terror.” This guy is on the sidelines of NFL games, things where people make their livelihood from their shoulder and have an injury. He’s jumping in there and fixing it. This guy can handle pressure, right? So it’s like why does somebody like this, such a cool guy die? Well chronic, lifelong anxiety, behind that smile, there’s a lot of smiley physicians out there. Maybe not in the room right now, but I know you see them. They’re cracking jokes all day. That might be a risk factor for somebody covering up their real anxiety and depression.

Be aware, physicians are masters of disguise. That’s why, with so many of these cases, nobody ever sees it coming, because he was just cracking jokes two hours ago, and the OR had just finished the surgery. And now he’s hanging in the surgical closet. How did that happen? You just don’t know, because doctors have been covering up their emotions for so long, especially guys, socialized in the country to be the fix-it man, not show anyone your true emotions. Well then all of a sudden your master of disguise compartment hyper-compartmentalized life breaks down in a moment in time, and then you’re hanging from a rope, or around here a gun shot. It just depends on the country. In India they’re hanging from ceiling fans by their saris. It just depends where you are. In a moment of desperation, you grab what you have, and if it’s your sari or your gun or whatever it is, you just get it. And you pick the closest thing, and that’s why … I don’t know, I’m sure I’m in a group where you’re not into super gun control or anything, but the point is, they’re going to find some way to die. If you take away their gun, they’re going to fill their car with whatever, with fumes. They’re going to jump from a bridge. They’ll figure something out.

Okay, and so he had marital and work distress. As you age, of course, your body needs more medical care. He had a medical condition. The thing that really drove him over the edge, his psychiatrist retired, passed him onto a new psychiatrist in the middle of all these things going on and gave them new meds, which did not work, and then basically just whatever, doubled the dose as I understand. And so this guy died by suicide at home, hanging himself because of shame and stigma. He didn’t want anyone else in Washington DC to know that he was anxiety ridden. He couldn’t risk to let the team know, the people that run all these special … He just didn’t want anyone to know. He didn’t want his colleagues to know, so he would rather hang himself on a book case at home. This is insane that we’ve created an environment where men can’t ask for help, and physicians can’t ask for help.

Just a quick story is one of the guys that I dated in med school, who died by suicide, when we were in a car before the GPS days, we were lost in the car. And I wanted to ask where we were. I just wanted to ask the gas station. He let me have it. “How dare you ask? I’ll just figure this out.” And he would not ask for help. We were lost in a car. What’s the likelihood he’s going to ask for mental health help once he has a white coat on on top of that? Not much, because he died by, as they say “accidental overdose” which I don’t believe for one minute with the methadone next to his bed. Doctors dose drugs for a living. We know the lethal dose.

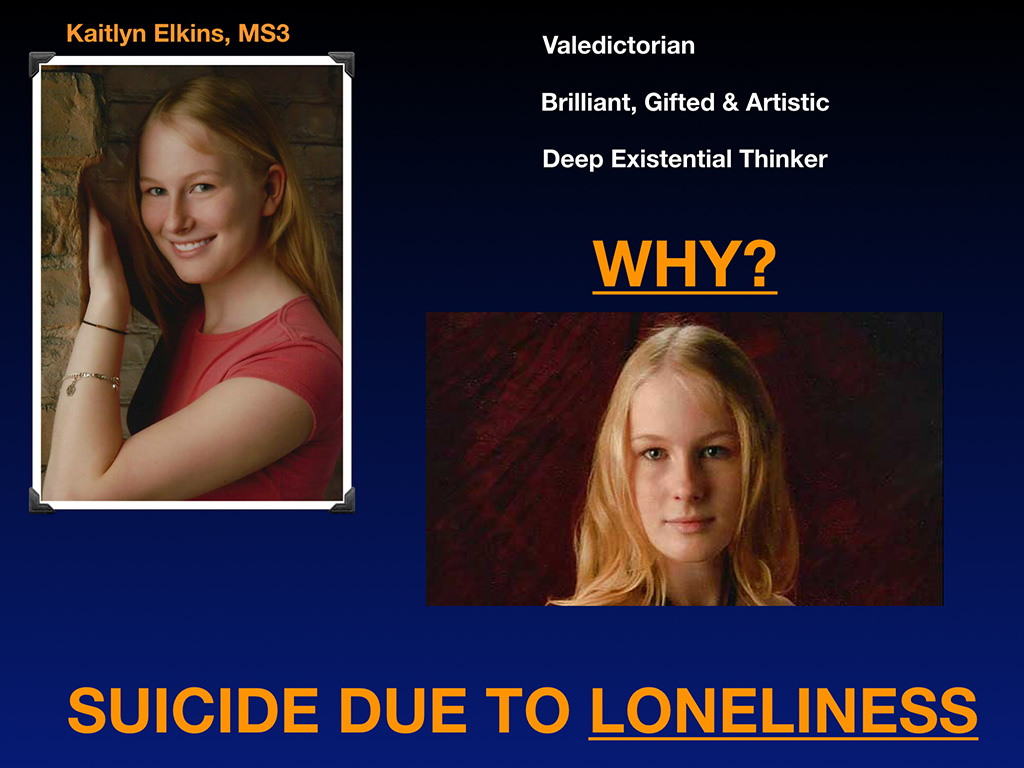

So here’s Kaitlyn Elkins, third-year medical student, star student, valedictorian, brilliant, gifted and incredible woman. Why did she die? Well, from loneliness, because in medical school it’s divide and conquer. Your success depends on your partner’s failure. If the guy fails next to you, maybe you have a better chance of getting a residency than he does. And it’s all about stepping all over each other for your own success, which is ridiculous. And by the way, that setup continues for the rest of our lives, much to the devolution of our whole profession, because that creates a lack of unity in which your attitude towards your classmate in first year of medical school persists your whole life. And you’re going to just step all over each other until our whole career is destroyed, and we lose our profession. That’s allowed many physicians predators to sneak in and profiteer off of us, making nice, passive income off of 74% of our hard work, which is what they made off of me in the big-box clinic.

So do people need to be dying of loneliness? Does that need to be happening? These are all preventable.

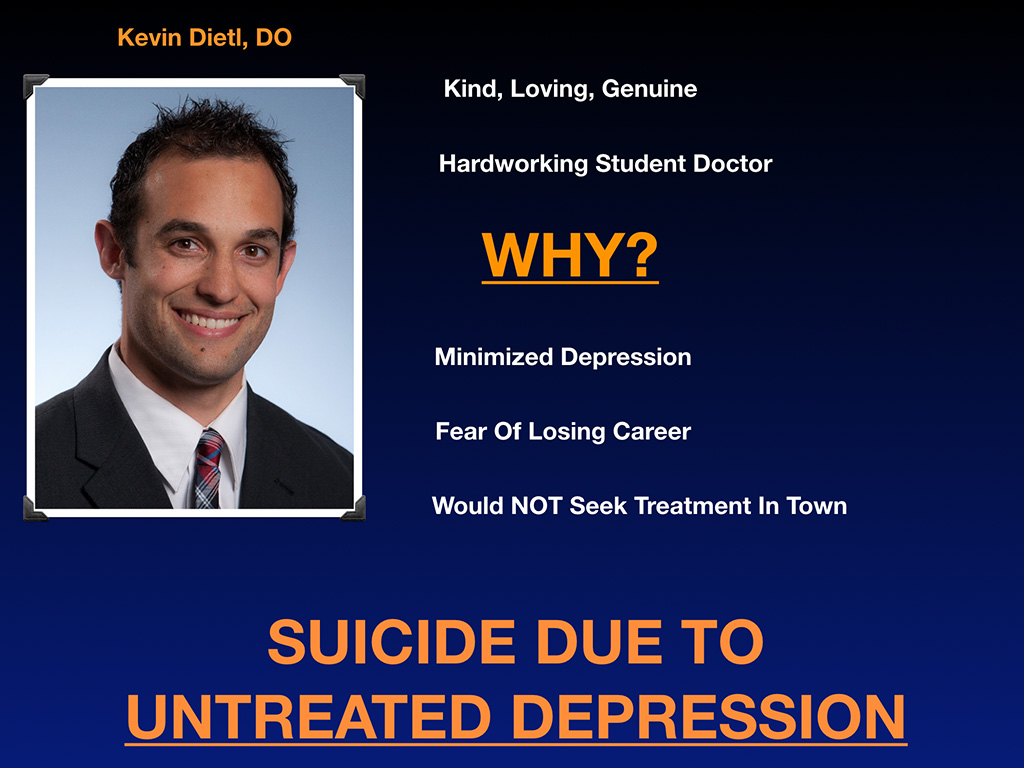

Here’s Kevin Dietl. He basically, you can tell, such a sweet guy, would’ve been a great doctor. Why did he die? Well, he minimized his depression. His mom knew something was wrong, but he said, “Everyone in my class is depressed. I’m just like everyone else.” Well that’s not normal. A whole class of medical students shouldn’t be depressed. We should start asking, “Why is that happening?”

And I don’t favor the term, burnout, by the way. Burnout in my mind is a victim-blaming term that blames us for situations that are out of our control. I think if we had time off and a normal life, we would naturally go on hikes and naturally enjoy ourselves and wouldn’t have to go to lectures on the importance of sleep after a 24-hour shift. In the military you have a forced wellness lecture now quarterly, and they allow the doctors to sign up for time doing adult coloring books. Well that’s kind of ridiculous. I think if you’re a doctor that wants to color, you would normally do that, if you have time to color, but not while you have 17 patients waiting, and they force you in a room with a coloring book in the military. It makes no sense. Forced wellness on the overworked, it’s ridiculous.

And so anyway, Kevin feared losing his career. He wouldn’t seek mental healthcare, so he died from untreated mental health issues. His untreated depression spun into psychosis. And then it was really a mess. He should’ve got help earlier on, but he was scared that it was going to ruin his chance of getting a residency. So of course there’s a lot of these people who shoot themselves right before their original graduation date.

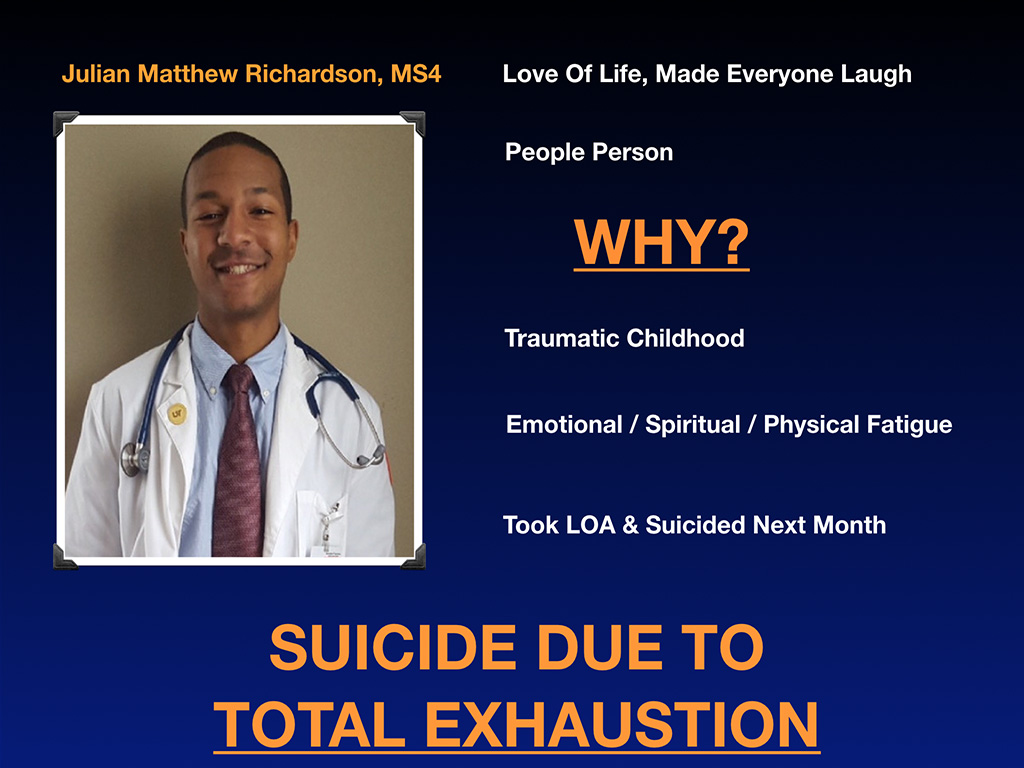

Another case of a beautiful, young man, awesome person. This guy had some traumatic childhood, which again, you’re going to get re-traumatized in medicine, when you see all this death and suffering. And so this guy was just basically completely exhausted, emotionally, spiritually and physically spent, and so he just died from exhaustion. Should people be dying from exhaustion?

Should physicians be dying from overwork. Which, by the way, in Japan, is illegal to work over 60 hours. If you die by suicide in a job where you’re working more than 60 hours, the cutoff is 65 for suicide, and for cardiovascular and others, threshold is 60. Your employer is then held financially liable. Okay, so why does the ACGME have residents working 80 hours a week? That’s two full-time jobs. Would you get on an airplane with a pilot working 80 hours a week? Nobody would do that.

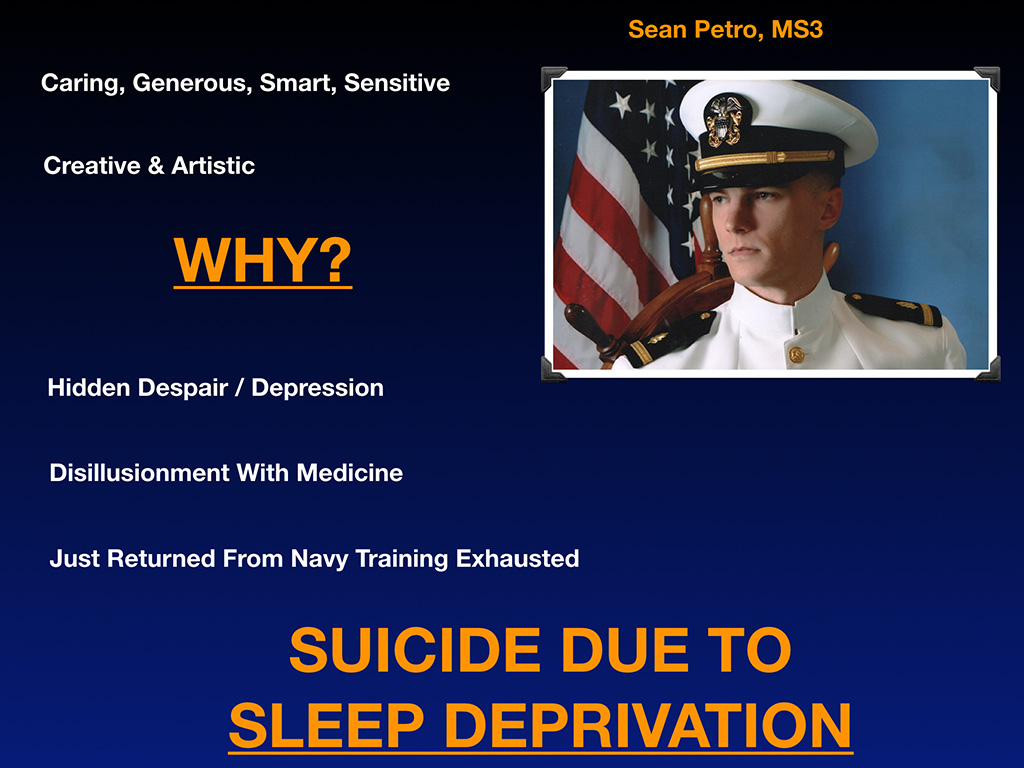

And this beautiful man, Sean Petro, another caring, beautiful, would have been a great doctor. His mother was infertile for 10 years, finally got pregnant. This is her only child. He died by suicide. We’ve allowed this to happen in our profession. I hold us responsible for allowing this to continue for 160 years and not doing anything about it. And of course when I talk to the mother, and they realize this has been going on for 160 years, and it’s not just their “defective” child, they’re outraged that we’ve allowed this to continue. He died by sleep deprivation.

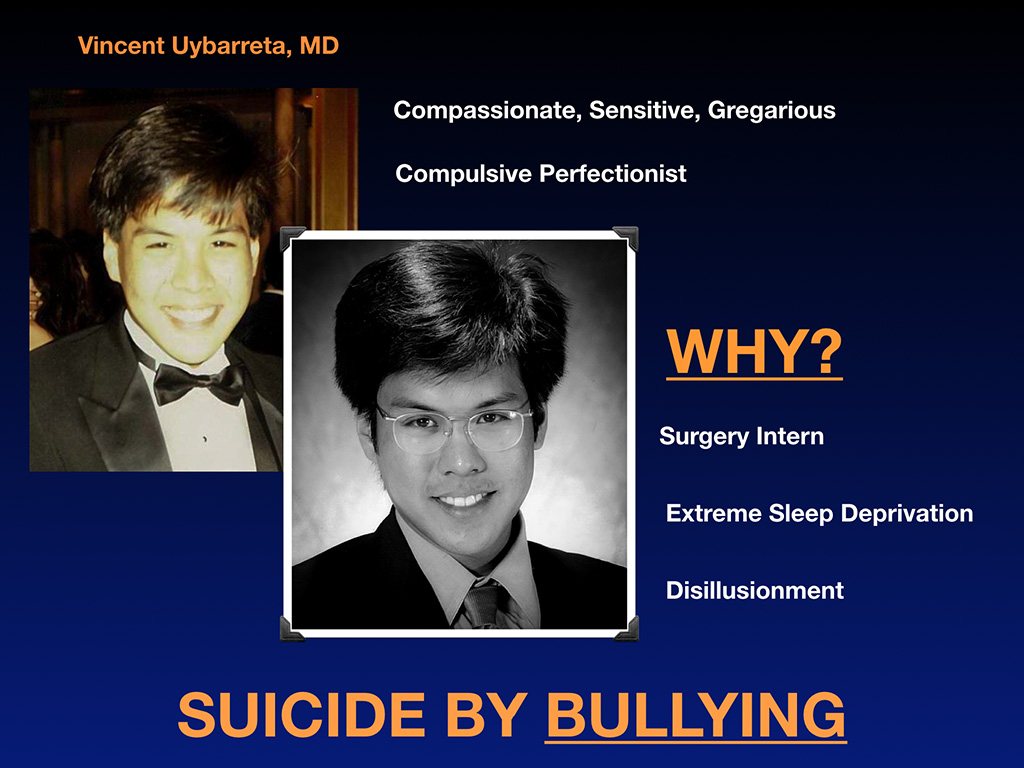

And Dr. Vincent Uybarreta, great guy, again would’ve been a great doctor. Look at the difference between him from graduating high school and graduating medical school. He died by suicide a few months after. Can you see the energy, and the life in his body has just been sucked right out? It seems obvious to me. I don’t know if you can pick that up. But anyway, why did he die? Surgery intern says it all in a program where there’s a lot of bullying. And so he basically succumbed to sleep deprivation and bullying, which is a very toxic combination.

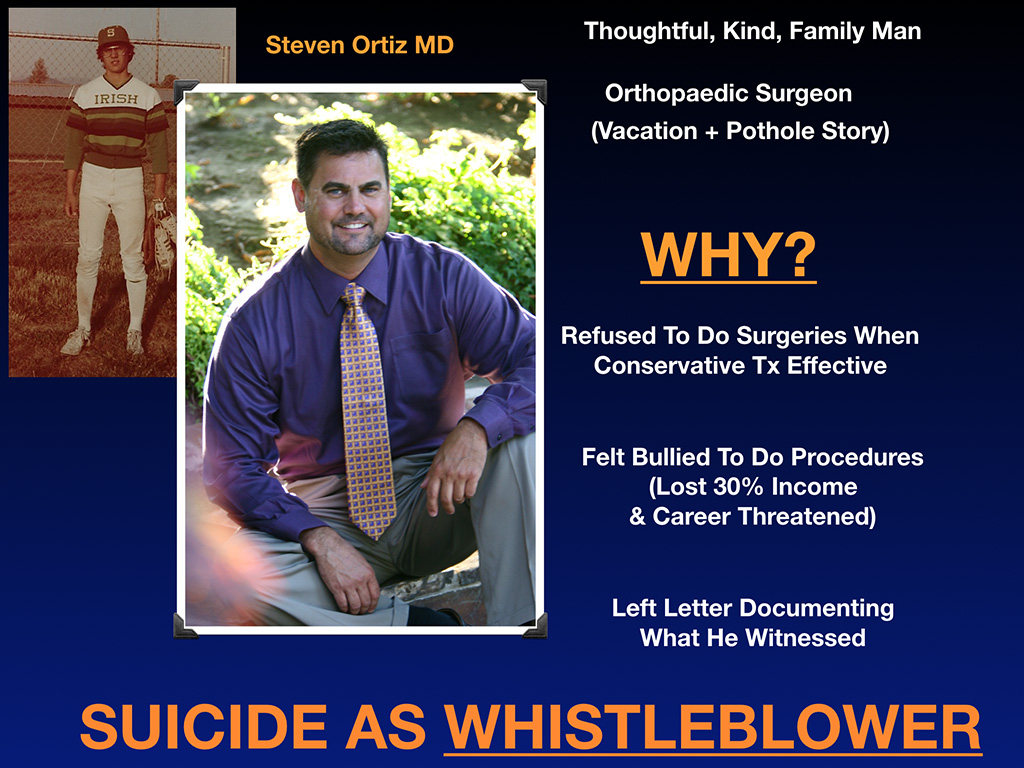

I love this man, Steven Ortiz, who grew up down the street from me, became an orthopedic surgeon. I never knew him. I only knew him in the aftermath of his death, because I’m close to his mom, incredible guy. These people are primo doctors. These are the doctors you’d want to go to. We’re not losing fringe characters that shouldn’t be doctors. We’re losing the compassionate, loving ones who are really smart. And orthopedic surgeon, I just have to tell you, such a cool guy. He’s done things that I’ve never even done, and I thought I was the Mother Teresa of medicine. He came home from a vacation to see a patient, who was sick. Who does that? An orthopedic surgeon who really loves his patients. There were potholes outside of the hospital, bad hospital admins, and he asked them to please fix them, because he’s a spine surgeon. And having your patients bounce up and down with spine surgery before and after on potholes isn’t good. They wouldn’t fix it, so this guy, previous career in construction, second career as an orthopedist, just went out before work one day with cement and gravel, and he just fixed the potholes in the parking lot himself, since the hospital wouldn’t do it, and then went to surgery.

His mom was like, “19 years of medical training and my son is out there fixing potholes in the parking lot of the hospital.” Now why did he die? Well, he refused to do surgery when conservative treatment would work for his patients. And that cut into the bottom line of the hospital. Like many people in specialties where there’s a lot of money to be generated from procedures, there’s pressure to do more, and that friction point didn’t go well. His income decreased, and he left a letter documenting what he witnessed. And by the way, your work ethic is the last thing to go so he’s checking on his patients, checking on critical labs, leaving goodbye letters to the nurse. Then leaves the hospital, sits in his truck over the new pothole that he fixed and shoots himself in the heart. So this is a guy that we lost as a whistleblower. Okay, this is happening over and over again across America. It’s not often in the news. We’re too busy working, getting 75% of our revenue stolen to understand what’s going on here. But I’m just trying to get everyone up to speed.

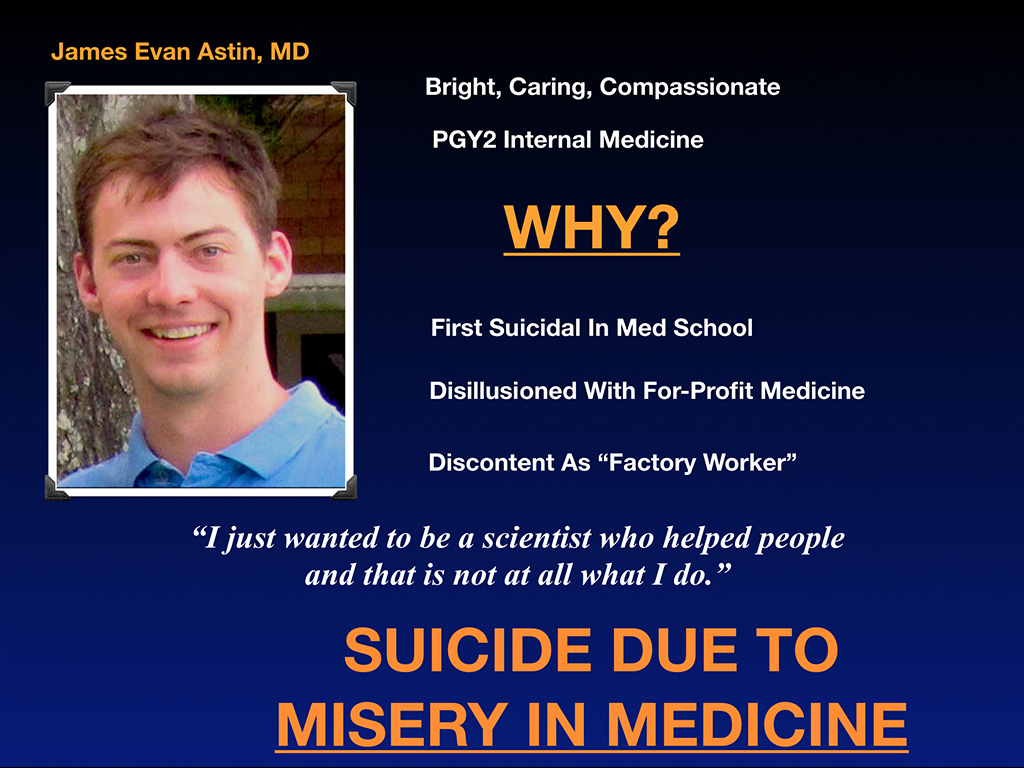

So here’s another beautiful man. Second-year internal medicine resident—Dr. James Evan Astin. Like many people, he was first suicidal in medical school, did not have preexisting issues, as the slides have shown earlier today, is that we came into medical school (as Lynn showed in her first slide set this morning) with mental health better than the general population and our peers in college. But students soon realize they’re being basically funneled into assembly-line clinics to be factory workers the rest of their lives, and they’re not really so tolerant of that. Evan told his mother before he died, “I just wanted to be a scientist who helped people, and this is not at all what I do.” So he died because of misery in medicine and shot himself in Texas, at his dad’s farm.

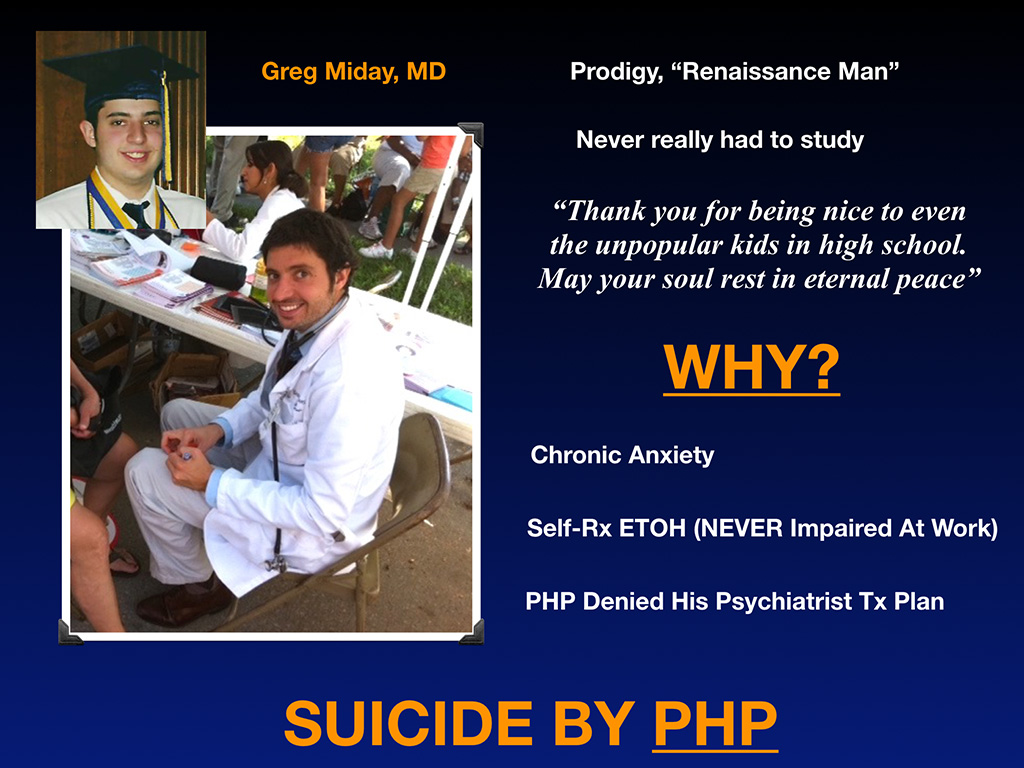

And this is Dr. Greg Miday. I love this dude. He is brilliant. So he’s one of those people that we all hate, because he never had to study in medical school. I was not like that. He never studied and he made straight As, spent all of his time helping other people trying to understand basic concepts that I’m probably still having trouble with. And you know he’s a great guy when years after he died, his patients are still writing on his online legacy page. “Thank you for not calling off the code on my husband. We had him for another five years.” Sorry you didn’t make it, but we had my husband for another five years. And people from high school thank you for being nice to even the unpopular kids. May your soul rest in peace. Here he is helping homeless women, my god. He had so much free time, because he didn’t have to study in medical school. He was out on the streets helping homeless people. I mean this guy is amazing. Why did he die? Well he had chronic anxiety, probably from being brilliant in a world that felt like special ed to him. He probably felt different, right? And so he self treated with alcohol, which in a way is his own business. If he’s never impaired at work, he should be able to relax the way he wants to at home. Well he chose to use alcohol, ended up in a PHP, which put him on a one-size-fits all track and bullied him 300 miles out of state, so he didn’t graduate on time as I recall. And he basically was sober for many years, complied within a program but then broke up with a girlfriend right before starting his oncology fellowship and started binge drinking just at that moment. Well part of his treatment plan is he had to turn himself back in. You turn yourself back in, they’re going to force you to go 300 miles out of state again, one size fits all. No special treatment for you. And he had a psychiatrist in town he was seeing that came up with a safety plan for him, so he could start his fellowship on time. He’s never endangered a patient. He’s the one that you want for your care in the ICU, even if he drinks at home, because he’s better than probably everyone else in the hospital. Okay, but instead they’re going to send him 300 miles away.

Anyway, they (non-physicians!) overrode his treatment plan. No doctors oversight in his physician health program and they overrode his personal psychiatrist’s treatment plan. And so he went home and slit his wrists in the bathtub because of the PHP. There’s a lot of suicides that involve PHPs. They are not uniform throughout the country. Some of them are terrible. Others are pretty good. We don’t really have a uniform and secure safety net for physicians who are suffering. Doctors are often ignored and enabled by their colleagues or harshly punishment, and there’s not much in between.

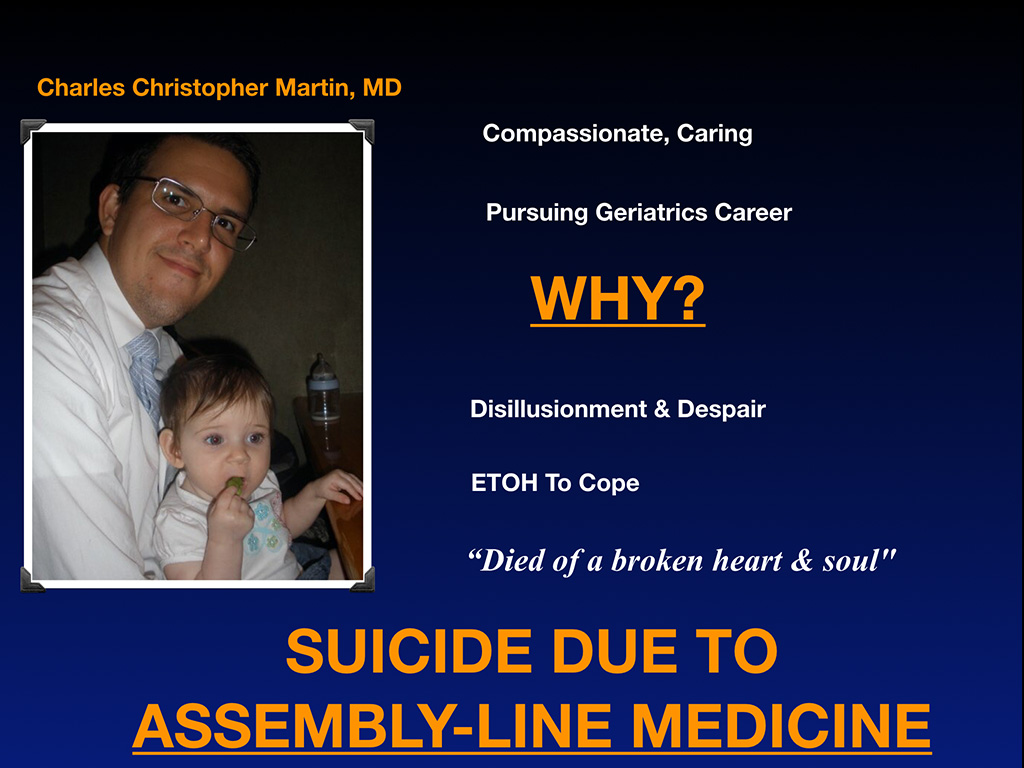

And so here’s a great guy—Dr. Charles Christopher—who would’ve been amazing geriatrician. Why did he die? Well he died of a broken heart and soul. According to his mom, he didn’t want to be an assembly-line worker. That’s all he saw in residency. How are you doing to do seven-minute visits for geriatrics. He didn’t see what future he had, so that’s it.

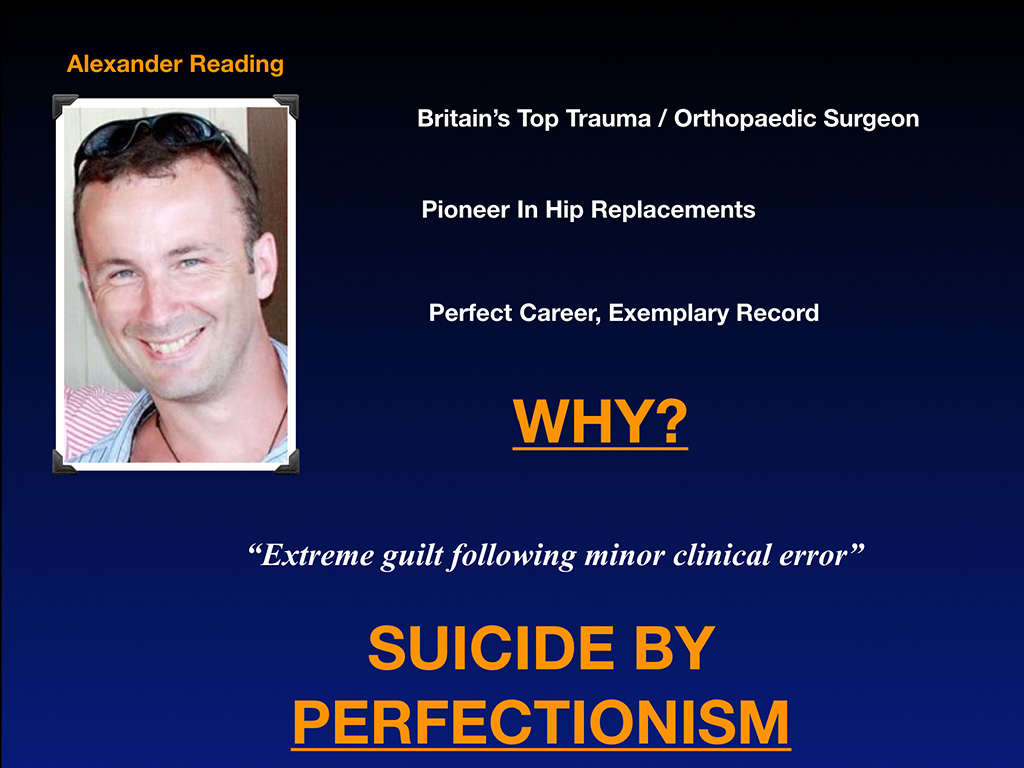

Dr. Alexander Reading was in Britain. I get cases from all over the country, Britain’s top trauma orthopedic surgeon. This guy basically couldn’t handle the guilt of a minor clinical error that did not kill the patient. He couldn’t handle it, so he died by perfectionism. These are very physician-unique situations.

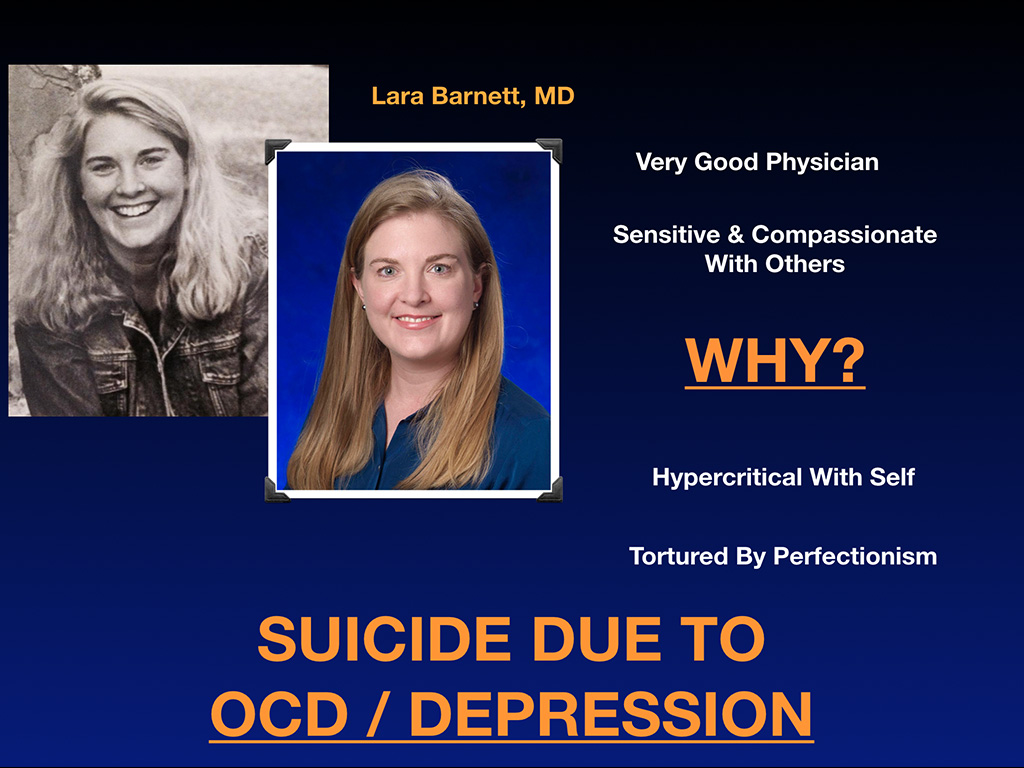

And another very wonderful physician Dr. Lara Barnett we lost to untreated suicide and OCD, personal, tormenting herself from a perfectionism and OCD.

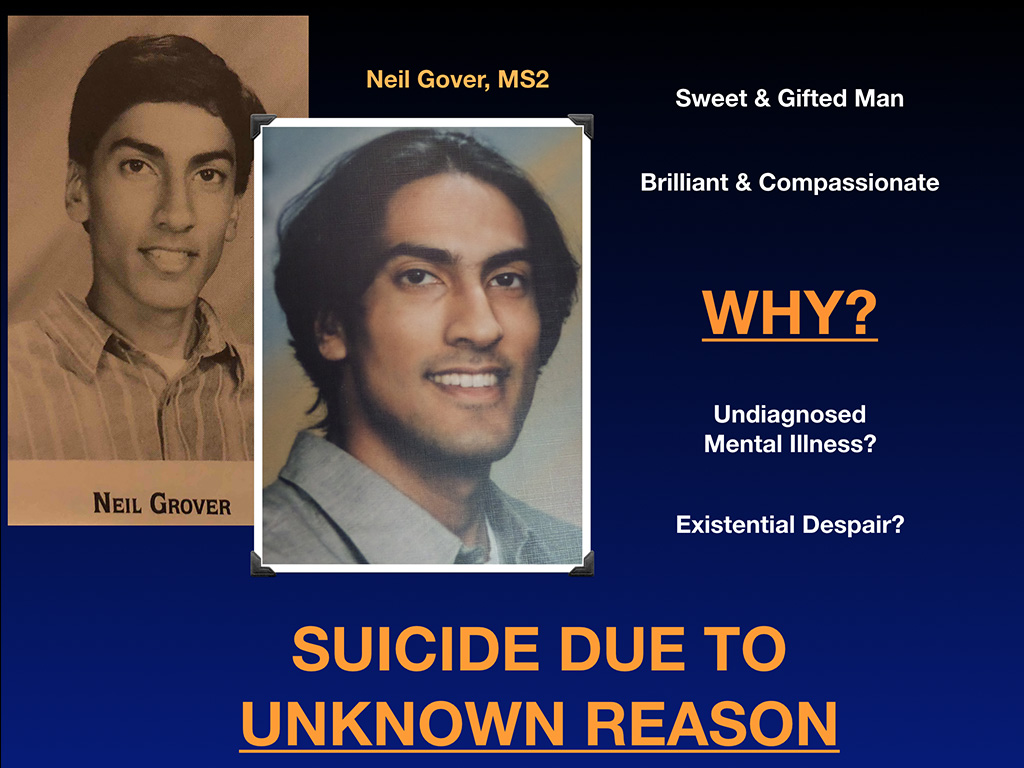

And then here’s another second year medical student, Neil Grover died. We don’t know why, suicide due to unknown reason. I think many of them are in this unknown reason category. Why are they there? I don’t know. We’ve never had a morbidity & mortality conferences to figure out why they died. So they just keep dying by suicide, and we keep pretending it’s not happening and sending prayers to the family and prayers for speedy healing. We need to actually address this as scientists. And so here are the 13 reasons why listed here.

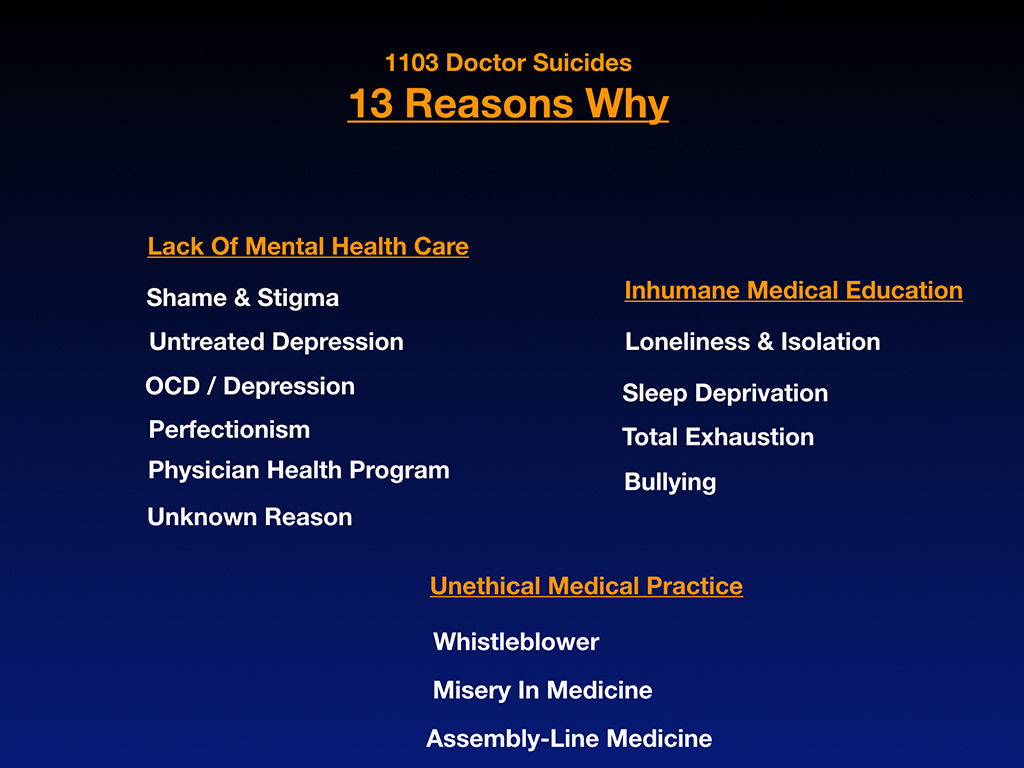

I think you have copies of these. I think you have a PDF copy of my slideshow, if you want to look through this later. I divided these into three categories, which basically we have a lack of mental healthcare category, and inhumane medical training category, which has a lot to do with why these people are dying. And they would’ve been okay as real estate agents and other professions. But because our medical training is warped and unethical medical practice is a problem, that’s killing doctors.

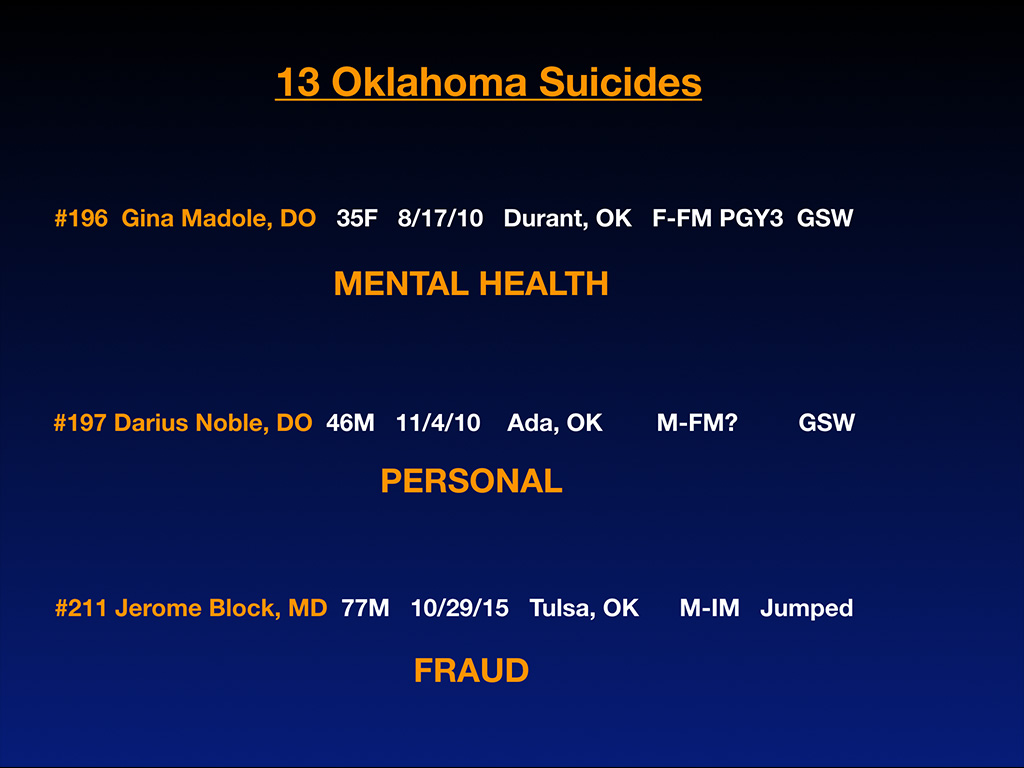

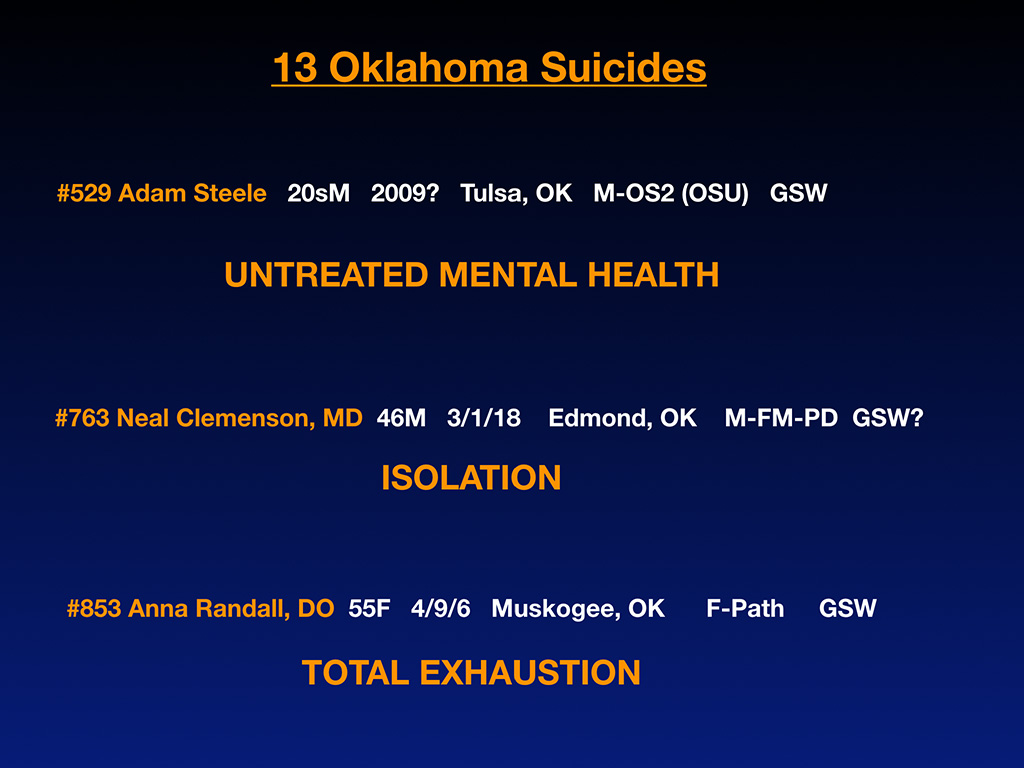

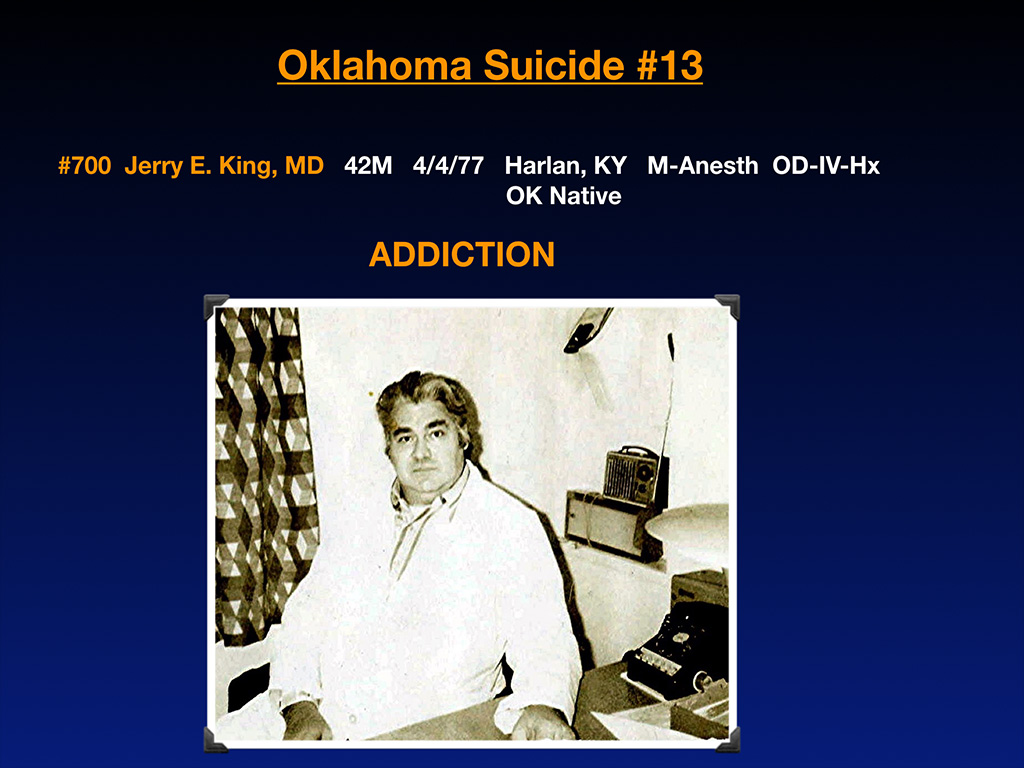

And so I’m going to just review with you 13 Oklahoma suicides. These are people you know, and I’m putting them up by names, case number and everything. I was originally maybe not going to do this, but out of the blue, weirdly, I was contacted by a Tulsa Police officer through some bizarre series of events, which I’m happy to describe later. And she told me all of these are public record, so you shouldn’t hold back. Share them all. And I think, yeah, that’s what we need to do, is just approach this like any other medical condition. These are people that we lost. This is exactly how it looks on my registry. They’re all by case number based on the organic sequence, that they came to me from people reporting them. Okay, so then there’s name, age, gender, date of suicide, location of suicide, specialty and the reason why, the backstory. And I have a whole other document where I saved all the millions of emails I’ve gotten from people giving me the really detailed backstory. I’m not airing people’s dirty laundry. I’m just giving you a thumbnail of what the situation is.

Case number 196 is Gina Madole, DO, 35 years old. She died in 2010 in Durant, Oklahoma. She was a third-year family medicine resident who died of a gunshot wound because of mental health issues.

Then we have Darius Noble, DO, who died a few months after that in Ada, Oklahoma. He was 46. I think he’s family medicine (every so often you see a question mark because I don’t always know if I’m quite right on a few details). It’s the information that comes to me from others, and sometimes it’s confirmed by their obituary. Sometimes they’re just missing a few little pieces. I’m not sure if his specialty was family medicine, but he did die of a gunshot wound, and he had personal issues, which I will not air publicly. By the way, in medicine, when you spend so much of your time with working 100 hours a week for professional success, you will have personal life atrophy. And so when you have that happen, you could lose your marriage, get divorced and have all sorts of other issues that you wouldn’t have if you were a real estate agent or worked at Starbucks.

Jerome Block, MD, 77 year-old gentleman, a physician, integrative medicine, internal medicine doctor in Tulsa jumped out of a building. I believe it was the 20th floor of the building, and this was due to fraud. He was caught in Medicare fraud, which is another problem that DPC will solve, because you won’t be coaxed into, I don’t know, putting a nurse practitioner in the room without you while billing under your Medicare number, or you won’t be inflating codes and doing all these weird coding and billing dances that could make you go to prison or be fined. Do you really want to do that? Do you know the Medicare codes or guidelines for legality and staying within the rules of Medicare is larger than the US Tax Code? Who’s going to make it through? I think the US Tax Code is like 75,000 pages, but the Medicare guidelines are like 150,000. Add that to the DPC slideshow, because who’s going to be able to follow 150,000 pages of guidelines? And the thing is, when you call up Medicare to ask a question, they don’t often know the answer. They send you to somebody else, and they might give you an answer that’s completely different. I mean you can never get to the bottom of what’s really going on with Medicare. Huge lack of transparency and yet your butt is on the line. If you under code, because you think it’s safer, you can get in trouble for under coding your visits. It’s unreal.

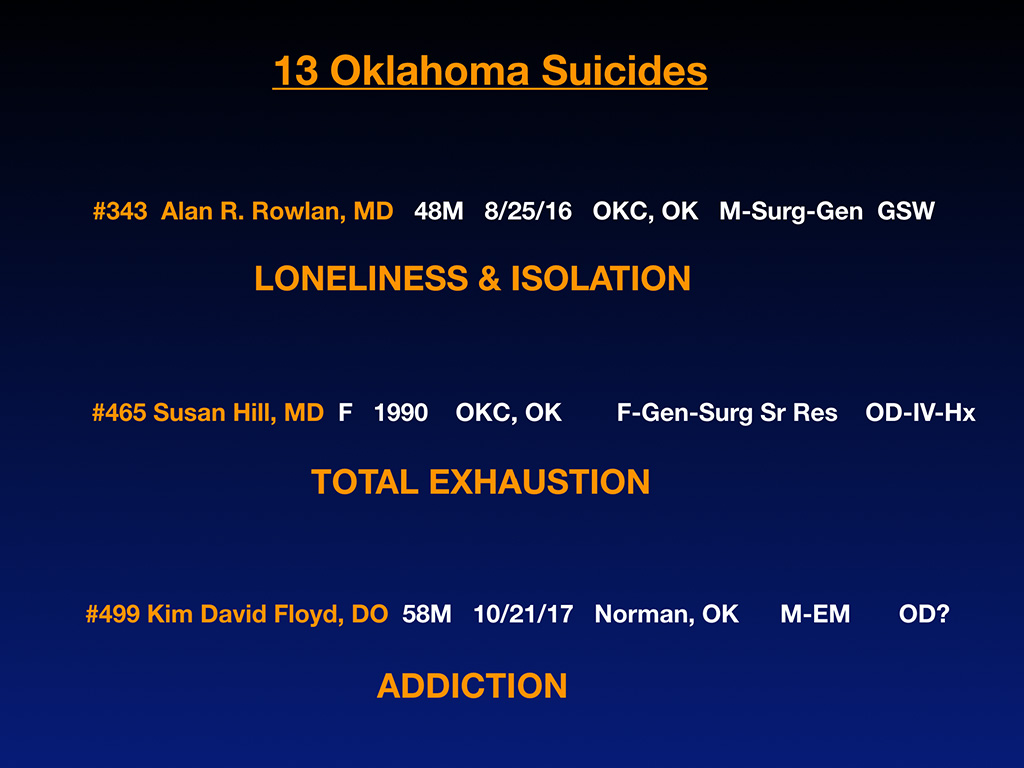

Alan Rowlan, MD, is a surgeon who died in Oklahoma City in 2019 of loneliness and isolation. Then we have Susan Hill, MD, from 1990, female general surgery senior resident who (like a lot of these surgeons and anesthesiologist especially) are dying in the hospital of IV overdose. She was just found in the hospital dead due to total exhaustion. And then we’ve got Kim David Floyd, DO, a 50-year-old gentleman who died in Norman, Oklahoma recently, in 2017, I think from an overdose. But he had an addiction issue.

And then we’ve got Adam Steele, very interesting. I just got an email an hour and a half ago giving me more information on his situation. I’ve had several of his classmates email me recently. He went to OSU, and I think now he died in 2009. He was in his 20s. It was in Tulsa. That was confirmed in an email I got an hour and a half ago that I didn’t ask for. This information just comes flowing to me synchronicity I guess right before my talks. So there’s two cases in here from OSU, and they’re both students who had to remediate. And they felt alone and isolated, like they didn’t get the help they needed to survive the despair and hopelessness of their situation.

Where’s the off ramp for if medical school doesn’t go well? Is there an off ramp? Or is it just your gun? Is that the off ramp? Because that’s not a good off ramp. These are young people who need help trying to figure out what they do with $100,000 in student loans, and they didn’t pass step one. They need help, and they shouldn’t just be hauled off and discarded because they don’t look good for the school or whatever. Sometimes we just don’t do anything to help them, and they’re little kids. They need help. I guess I can say that, since I’m 51, but they’re sweet people who had the best of intentions. And so we had untreated mental health issues and maybe substance abuse issues. I don’t have the full story. These are just things that have flown in to me by classmates. I do know these are legitimate suicides.

This is the one that I think you were referencing Kyle. Neal Clemenson, MD, was the program director in family medicine from Edmond, Oklahoma. He recently died, last year, May 1st, by a gunshot wound, I believe, due to isolation, is what we think based on the information that I have. He’s nodding, so probably on track there.

Then Anna Randall, DO, some of these are in the news. She was in the news, because they were looking for her, because she was missing. She’s a pathologist. They found her with a gunshot wound by, I don’t know, her riverfront home or something in Muskogee, if there’s a river there, the lakefront. Anyway, she died, as it was declared in the article, exhaustion. She was just exhausted. She had to sell her practice. This is an exhausting profession. You could die from just being exhausted and having no time for your family or fun or eating or sleeping and stuff like that.

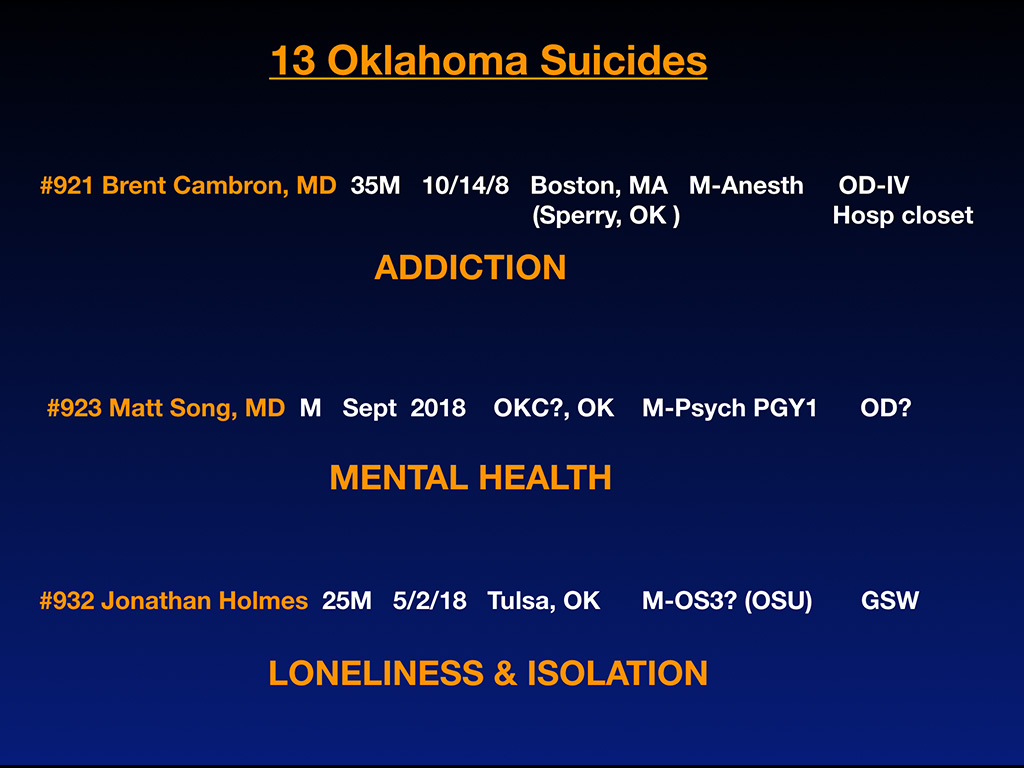

Brent Cambron, MD, was in the news a lot. He was the star child from Sperry, Oklahoma, which I guess is a small town, ended up in Boston as the star anesthesiologist there until he was found dead of an IV overdose in the hospital closet, addiction.

Okay and then Matt Song just is the most recent one who died in Oklahoma in September, 2018, Oklahoma City, first-year psychiatry intern of, I think, an overdose, mental health issues, I think. I don’t have confirmation on some of this. It’s just the best guess based on what I have. (I was also forwarded the announcement of his suicide by his program thankfully being very open about his suicide).

Jonathan Holmes is a student who died a few weeks before he was to graduate with his class at OSU. But because of remediation issues, he was just sitting at home, looking at all his student loan paperwork, wondering probably what he was going to do. So he said I better just end this pain for my family. Now he has a tight-knit family from around here I’m told. His best guess for what to do was using a handgun. We’re leaving our best and brightest students alone with handguns and no help and no off ramp, and they don’t need punishment, and they don’t need people to ignore this. They need actual help (especially around the time of their original graduation date).

Here are the 13-plus reasons why. I’ve highlighted the ones that are significant for the 13 Oklahoma suicides.

And the reason why I have 13 twice in here, it was really odd. I thought I might as well include some suicides from this local region to try to pull people in. Maybe they’ll know some of these people, and it will impact them and want to do something. And so I went on my list of close to 1,200 now, and there happen to be exactly 13 from Oklahoma. So who knew? Just worked for the talk.

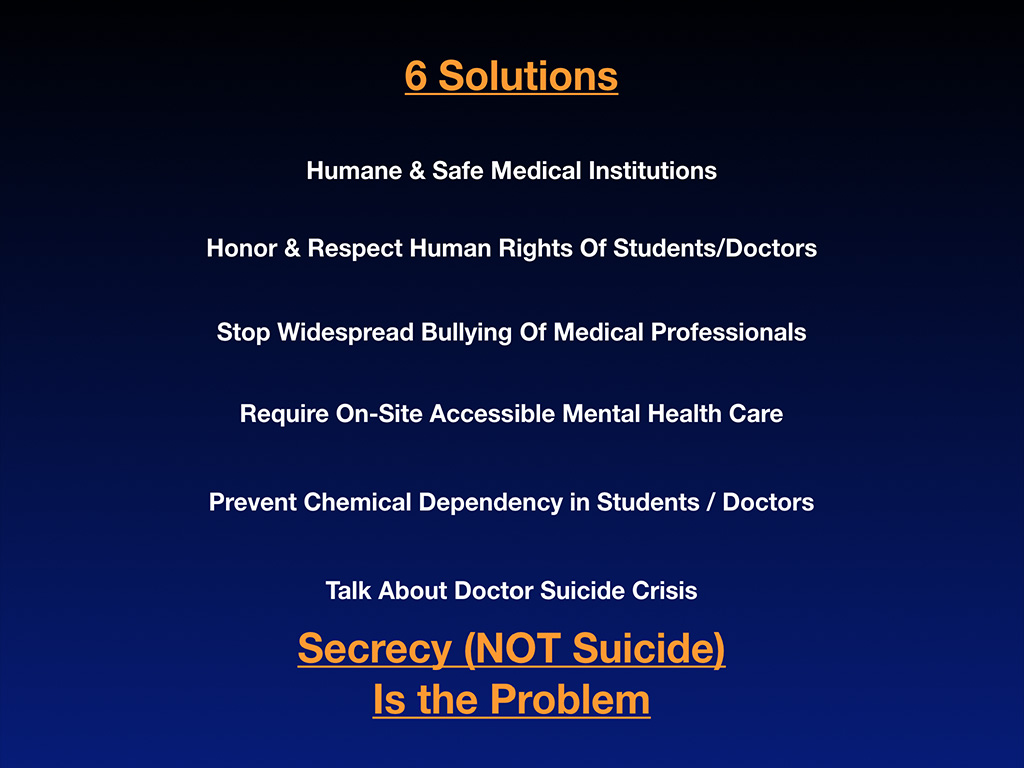

And here are some solutions. Obviously we need a humane and safe medical education experience and medical institutions. We do not need to be putting out best and brightest in unsafe situations and unethical environments where they’re learning to be doctors by watching other doctors lie on the computer in the hospital about the review of systems and all sorts of other things that teaches, you, because it’s an apprenticeship profession, that it’s okay to lie on the hospital computer, including if they put more than 80 hours, and they work for a week. The hospital computer locks up and makes them lie in a lot of residency programs. And so what is that teaching? That’s teaching our future physicians to lie on the computer, not good, unsafe, unethical, not good for patients, not good for fraud. You get caught up in fraud that way and want to kill yourself before you get called into the medical board.

We need to honor and respect the human rights of our students and doctors. I think we’re out of touch talking about burnout. I personally don’t even believe in the word. I think it’s a victim blaming, shaming term that has been distorted. Originally a term used for drug addicts in 1972, it’s a slang word. Somehow it’s now applied to all doctors in 2019. Makes no sense to me, because really what’s happening is we have chronic human rights violations in medical education and training. When I say I don’t use the word, burnout, people ask, “Well what word would you use? What would you replace it with?” Let’s replace it with the truth. “Try these three words—human rights violations. Those are the words to use, because we’ve been talking about burnout for 40 years. And we still don’t have a solution, and everyone’s eyes glaze over when you talk about it over and over again. Meditation and yoga is not the treatment for human rights violations.

I don’t know how many of you guys in here got in your yoga pants this morning, but I don’t think that’s the solution. I really don’t. (Yoga is awesome but not the treatment for human rights abuse). I think we need to talk about the truth. We’re scientists. Let’s talk abut the facts. The facts are sleep deprivation, exhaustion, work hours that are illegal in other industries and illegal—punishable criminally in Japan. Okay, and we’re letting this happen to our own people in our own profession. It’s unreal. So I want to stop the bullying. It should be a safe zone like in elementary schools, no bullying. Maybe we could do that in medical schools too.

And require on-site, accessible mental healthcare, because let’s just face it. We work in the ER. If you don’t have mental health problems doing that job, you might be a sociopath. People are dying in front of you, and you have to tell people, “Sorry, you have a stillborn.” If you’re not crying from that, something might be wrong with you. I really think we need to have on-the-job mental healthcare, so we don’t have so much PTSD in our emergency workers. And that’s why I think the surgeons, the trauma surgeons and emergency and OB/GYN are highest on the list. They’re traumatized by their daily work, and they need help. And we need to prevent chemical dependency in students and doctors. We need to talk about doctor suicide crisis.

And by the way, the good news is we really don’t have a suicide problem. What we have is a secrecy problem. If we didn’t have secrecy, we would’ve solved this 100 years ago. But because everyone is hushing it up and quoting Bible verses (I have nothing against the Bible, but I don’t think the Bible is the treatment for diabetes and other serious medical conditions) There are certain conditions that require meds and a different sort of algorithm. And I’m all into prayer and helping everyone heal, but unless you’re … What’s that thing? The Christian Scientists, and some people think you can heal from everything from praying. Maybe you can, maybe in some cases, but I’m not against anything. I’m just for the facts and not hiding things.

Okay, and so this is our 13th gentleman that we lost to suicide, and I’m just going to share his story, because I’m very close to his daughter. He died in 1977. His name is Jerry King, he died in Kentucky, but he’s an Oklahoma native, and he was a male anesthesiologists, of course there. I love the picture, very old school with the little radio and his phone. And he did have an overdose in the hospital, like all of the anesthesiologists here, died by an addiction.

And I have a letter from his daughter I’m going to read, because here’s his daughter in his arms after her birth, his daughter hugging him as a toddler. And there we’ve got her at 14 years old. This is a letter from her. She’s in her 50s now. She wants me to read this to you.

“My father was from a poor family in Oklahoma and the first to go to college. He father didn’t even make it to high school. Dad graduated from the University of Oklahoma Medical School and became and anesthesiologist in 1964. He was on the first team to successfully reattach an amputated arm. The surgery went so well that the patient became a pottery artist. I have one of the pieces in my home. Unfortunately, during that time that he went through residency, it was not uncommon [as I know many of you recall] for drug companies to send samples to med students, residents and doctors. It was at that time that my father became addicted to uppers and downers in order to make it through the long hours. In his mind, the drugs helped him accomplish his dream. But in the end, they also took it away. Many times over his career, he was caught using drugs, and his fellow doctors and the administrators would hush it up and move him to another town in another hospital out of some twisted combination of loyalty and shame.

Thing was, my father was excellent at what he did, a gifted physician, wonderful teacher. Hospitals and universities were glad to have him at first. And then the meds would start missing, and patients that needn’t had died, did. After he got caught in Lexington at Saint Joseph’s hospital, while he taught at the University of Kentucky, they took away his drug license. He then found a job in Harlan Country, Kentucky at the Harlan Appalachian Hospital, where somehow he was able to not only teach but once again be in surgery. Don’t ask me how they allowed an anesthesiologist without a drug license to be involved in surgeries, but they did for a year. But this time when he got caught after meds were missing, and a woman died, he was told that they would have his medical license pulled. He went into work that Sunday morning and, according to the coroner, went into the surgical dressing room and shot himself up with enough medication to kill 20 men his size. One of his students found him. I still remember them coming to my house.

[She was 14 at the time. See the picture of her? That’s how old she was when this all took place, okay? So just listen to what this child went through. And we’ve set this situation up this way, so that she had to go through this. They came to us. I was talking in detail. She said she can’t, she’ll never forget this moment, of course. They lived up on a hill. It’s impossible to get there. When there’s cars in the driveway, you know when there’s five cars in the driveway, only two fit in the driveway, and three are on the lawn. And there’s all male doctors in the house and administrators surrounding her mom when she walked in the house. And the first thing her mother said, “Well at least we have the memories.”]

I still remember them coming to my house. My mother, who had been an active alcoholic for a number of years, was incapacitated and had no memory for six months. At 14 I had to notify my grandmother in Oklahoma of her son’s death and arrange my father’s funeral. I still have the canceled checks, where the local banker, who knew the situation, allowed me to sign in my childish scrawl the check for my father’s casket. Chemical dependency among medical personnel has to be addressed, whether it is the stress of the addiction or the repercussions of the addiction, patient deaths, loss of family, loss of license, law suits. Chemical dependency plays a serious part in physician suicide. If we don’t better communicate the issues of chemical dependency with premed students and rid the profession of the enabling of fellow staff and administrators and eradicate the shame of dealing with addiction, we will continue to lose patients and medical personnel. I know all too well how deadly that silence can be.

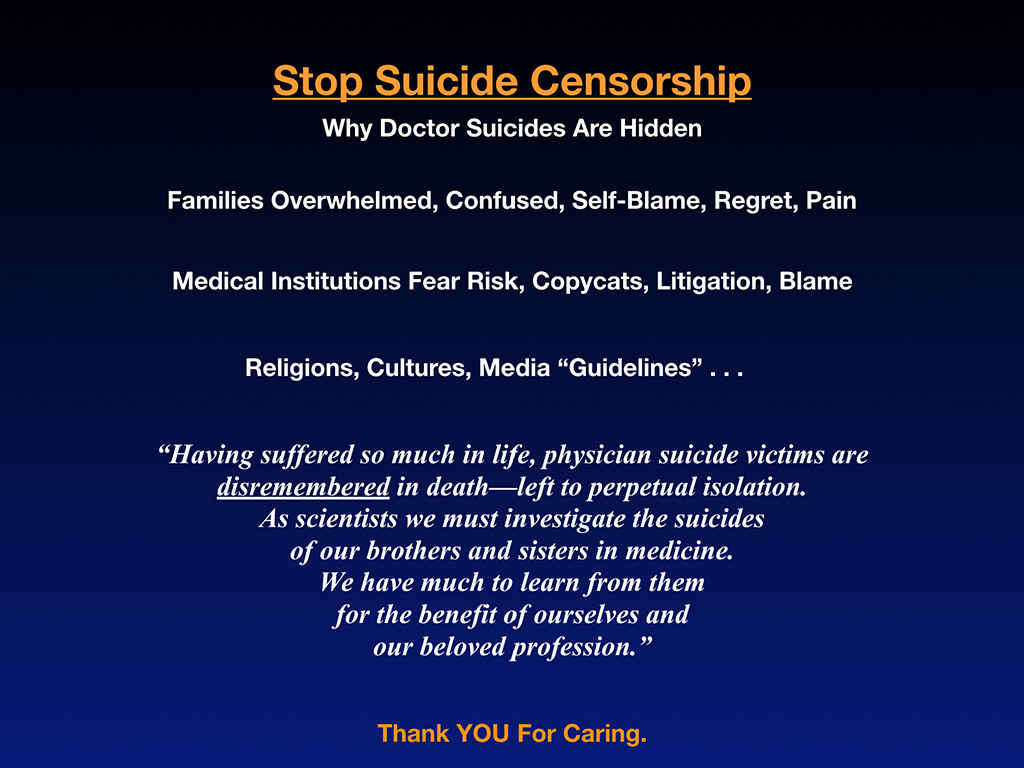

So I am here to please beg of you to help me stop the censorship around suicide and especially medical student and physician suicide. If we’re going to be of any use to veterans and everyone else that’s dying of suicide, we have to set the gold standard for how you handle mental health and how you deal with suicide.

Doctor suicides are hidden by other doctors and by families and medical institutions and the media . . . Here’s why they’re hidden. Well, the families are overwhelmed, confused. They’re blaming themselves. They have all sorts of regret and pain. You cannot leave it to a family in deep grieving, who just lost their star child or their husband in the prime of their career to deal with this. How are they going to deal with this? They’re crying in bed. They’re incapacitated for six months with alcoholism. They can’t deal with this.

Medical institutions that could deal with this are too worried about CYA for risk, copycats, litigation. They’re worried about being blamed, so they don’t want to do anything about it, because it’s like bad PR. You don’t want to be known as the hospital with the highest number of doctors and residents jumping from the rooftops. Now if the family doesn’t want to deal with it, because they can’t, and the hospital won’t deal with it, but that’s what they should be doing, if they really are, like the billboard says in town, providing the most compassionate care, then what?

Religions don’t want to deal with it and suggest that you’re burning in hell. That’s not popular either, cultures, people trying to preserve their reputations in the aftermath. And then we’ve got the final nail in the coffin, is suicide media guidelines, which I can’t stand, because they handle suicide differently than beheadings, kidnapping. Everything else is on the front page of the news. There are murders, rapes, everything else—except suicide. We’re adults, and we’re reading about the true facts of what’s going on in the world. But suicide is not reported like everything else, because you’re not allowed, because you’re not allowed.

But we’re adults, and we’re scientists. And isn’t it time to be allowed to talk about suicide? As medical professionals when will we be able to review these cases? We’re not going to solve this epidemic if we don’t talk about it.

So I’m asking you today to understand that these beautiful people that we lost—who saved countless lives while they were alive, but nobody came to save their life before they died—have suffered so much in life. Physician suicide victims are dis-remembered in death, left to perpetual isolation, which is what killed them in the first place. As scientists, we must investigate the suicides of our brothers and sisters in medicine. We have so much to learn from them, for the benefit of ourselves and our beloved profession.

And in parting, I want to thank you for caring. I assume that you care, because you’re here. I would like you to care as much as I care, and I’m going to take questions in a minute. I do want to mention that I have a book that’s free, called Physician Suicide Letters—Answered. I know it sounds depressing, but it’s actually really uplifting, and it’s a free audio book that you can download and listen whenever you want. It’s on my website at IdealMedicalCare.org. Just click on books, and there’s a link for a free download. If you like my voice, and you want to hear me for three hours, it’s even better for three hours. And you know what? This is like being a fly on the wall during my suicide hotline that I run for doctors. So you’ll hear some of the things I actually say to doctors, that maybe you want to use some of these lines yourself. As long as we can save lives, that’s all that matters.

As a profession it is very important, how we honor our dead. Every profession, all sorts of people that die, there’s often some sort of a public display that pops up. Even drunk drivers on the side of the road who killed entire families going the wrong way on the highway, they still get a little white cross with teddy bears. Everyone gets something, public display. Robin Williams there, the actor, he has a whole sidewalk display. He killed himself by suicide. And then right before a doctor who’s covered in a tarp there, you might notice the doctor gets nothing. But the football player, the middle, top there, quarterback died by suicide at the University of Washington, and within hours everyone had, “We love you, Tyler,” balloons, and the students were crying, holding candles.

Public display of grief is normal. That’s normal, that police officers that are killed, suicide and homicide, whatever, they actually will name a whole highway after you. You’ll be traveling down the highway with the name. I don’t know any highways named after doctors. I don’t think we’re handling these very well in the aftermath. We’re ignoring them. We’re not naming highways after them. And the teenager there, this is 10 years after she died. They’re still coming to visit the area where she walked into the sea there. And this middle one at the bottom is a bicyclist in Eugene. We have a lot more bikes probably and bike lanes than you do in Oklahoma. But the point is, there are people who are killed by motor vehicles on bikes all the time. And I don’t know if you have these here, but they’re ghost bikes. They’ll paint a bike white and keep putting flowers and everything this is 10 years after this guy died, downtown Eugene, Oregon, still a ghost bike is there. Everyone passes by and remembers this guy now.

A year ago on the 18th of this month, Dr. Deelshad Joomun stepped off Mount Sinai, one of the buildings there. The houses 450 doctors. She was the third one there that died within two years, and they covered her in a tarp. There she is, hand hanging out of the tarp and left her there for hours. And then finally the police came and threw her in a body bag, and that was it. Her family lives overseas. She was a J-1 visa, so nothing was going to happen.

I got three emails within an hour of Deelshad’s suicide, and they were imploring me—commanding me—to do something. So I wrote a blog called “Where are the Candles, Vigils and Flowers?” Because I was kind of upset that it was just a tarp. The minute we stop generating revenue, especially if you’re bloody on the sidewalk, then you’re a problem for the big-box clinic. Then they want to sweep it away, get the blood off. They don’t care if you live or die, as long as there’s people in line to replace you. Warm body, billing and coding, that’s what they’re interested in. And so I’m just telling the truth. I’m not trying to be a downer. This is just the truth. You’re replaceable, and when you’re on the sidewalk, you’re not only replaceable, but you’re like a stain on your image.

So I flew to New York City, and I don’t even know this woman, led a 10-hour funeral for her in which people came in from her students that went to school with her in Dubai showed up. I didn’t even know this woman. I just put it on social media. People came all day long to honor her and grieve. I led a candlelight vigil. I was told by the school, by the way, that if any media show up, they’ll be arrested. Can you believe that? I was like, I’m not the person you want to provoke. Did you just say that if media show up they’re going to arrest them? So I told the filmmaker, who’s doing the film on this topic of physician suicide. She said, “Hold on a minute. Let me get a camera crew there. Just pause.” So I put it on pause, camera crew came, filmed this event. And now it’s the first scene in a documentary coming out on physician suicide prevention. View Do No Harm film trailer here.

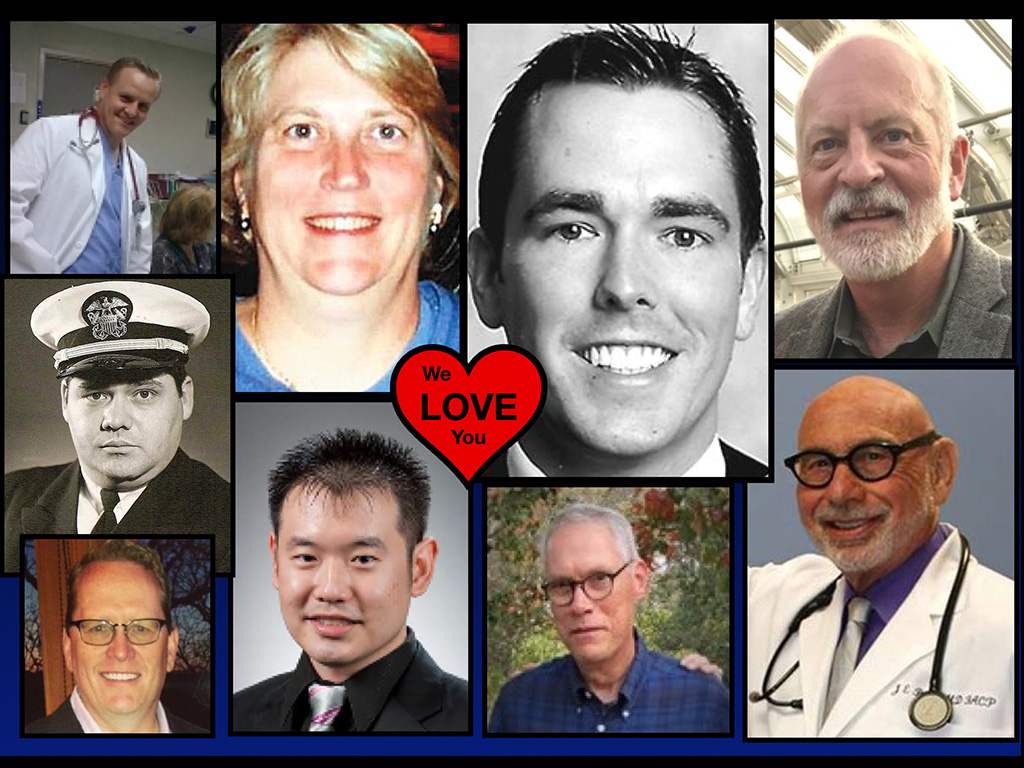

And so I’m imploring us to stand up for our brothers and sisters and remember these beautiful people. These are Oklahoma physicians we’ve lost to suicide. You might know some of these people. We’ve lost these people. They should still be here. Why are they not here? I’m asking you please to stand with me in not allowing any more of our beautiful physicians in Oklahoma to die before their natural death and to look out for your brothers and sisters. Thank you. We’re going to do Q and A at 1:30, so if any thoughts have come to your mind through this conversation, feel free to come back at 1:30. I will answer any of your questions, and I’m available whenever you want to pull me aside in the hallway. If I’ve got any details wrong on any of these suicides, I’m happy to update them for you. Thank you.

Addendum: Doctors at this event submitted 12 more Oklahoma physician suicides that were not on the registry. Sadly, doctors will continue dying by suicide until we bring this topic out of secrecy and discuss these cases honestly so that we can learn how to prevent future suicides. If anyone needs to speak with me, you can contact me here.

Pamela, thank you for the work you are doing and for getting our loved ones’ stories out there in an effort to prevent more deaths and more suffering by future families. I hope in this small way that through his story my father is once again healing and preventing pain.

Labor of love and thank YOU for being such a courageous woman with a strong voice and leading the way in ending the doctor suicide crisis by simply sharing the truth of your life. Ever grateful. I bet your daddy would be proud of the woman you’ve become. XO Pamela

Dear Rene, Thank you for sharing your story, its so important.

Pamela, Thank you so much for your important and significant contribution to society. The momentum is going in the right direction. The ACGME incorporated the requirement for “confidential” mental health services and the FSMB and the AMA recognized the fear of medical board actions as a barrier to mental health treatment. There is a formal recommendation to alter the question on state medical board licensing applications by the AMA and even a suggestion not to ask any mental health questions at all by the FSMB. However, with regards to the ACGME, the requirement for confidential mental health access appears to have been a long-standing requirement that may have been removed in recent years, oddly. It was a requirement in 1999 and it may have been there prior to that. It was clearly not enforced though. There are still other problems. The ACGME posted a statement which promotes the maintenance of the absolute power of the program director. I guess the new “Physician Wellness” Taskforce is unaware of the connection. I pray that malevolent forces have not penetrated the ACGME in efforts to thwart the movement toward fairness and humanity. Those in power will try to hold on to that power. Lets see what happens with the ACGME. Also discovered finally, that which I knew to be true, female physicians received lower performance evaluation scores. This was one of the personal truths I was trying to identify in my research. It is more than just scores though, the comments….. Anyway, I have much work to do. The legal system is still a huge problem. The information has to be presented with evidence of truth. Judges and lawyers do not believe what we know to be true about residency program directors, bullying and the underground network of communication and blacklisting. How can we prove what is not transparent? I am still battling the California medical board. I will keep you updated.

I graduated med school in 1976 and have had to make a few career adjustments to preserve my sanity…they were hard, because they were things that the average doctor just didn’t do, but I am so happy they were made. Things are harder now…years ago there were more private practice situations you could get into, often with just an informal “handshake” agreement. The mass employment of physicians by huge corporations is not good…all this debt is not good. Physicians should be self employed, or as in my case, employed by a doctor owned organization in which you are a stakeholder. You cannot serve two masters.

” . . . years ago there were more private practice situations you could get into, often with just an informal ‘handshake’ agreement.”

WOW how times have changed!! The native habitat for a physician is rarely as an employee. Most docs are by nature business owners or entrepreneurs. Big-box assembly-line medicine is such a perverse way to deliver health care.

Mark, way to go. Self-preservation is the prerequisite to delivering any medical care. Glad you survived.

Pamela:

You are truly remarkable in trying to bring ANYTHING to the forefront in the oh so corrupt U.S. Medical Industry. I really admire you and your efforts.

Besides hospitals and their “clinics”, my view i that GPs are the worst. 20-minute doctoring is a fraud. Does that group include the FM and IM categories in your suicide data? I know a little about Anesthesiologists so am not quite so surprised at their frequency. Surgeons still surprise me a lot.

If your practice time permits, I might like to fly out from Tucson for a personal review of my own GP situation. I consider it appalling; but given your priorities, it might seem minor to you.

If you would like a second opinion by a brilliant doctor who can put you on the right plan of action, I’ve got the woman for you! (I’m not taking new patients at this time for obvious reasons).

The lab model for inducing psychosis in primates is to make the primate responsible for an event it does not control.

Pam,

I knew one of those mentioned here. He was deeply kind. I was his teacher for a brief few sessions. He was inquisitive and wanted to do well. His memorial was eerie, I’ll never forget it and I don’t ever want to be at it again.

Thank you as always for memorializing our colleagues.

How could the memorial have been better? More of an honoring?

I don’t think it could have been better. It just was what it was and it honored him/her well. I was a supporter of some mental health programs before but it changed me to have a face to the crisis.