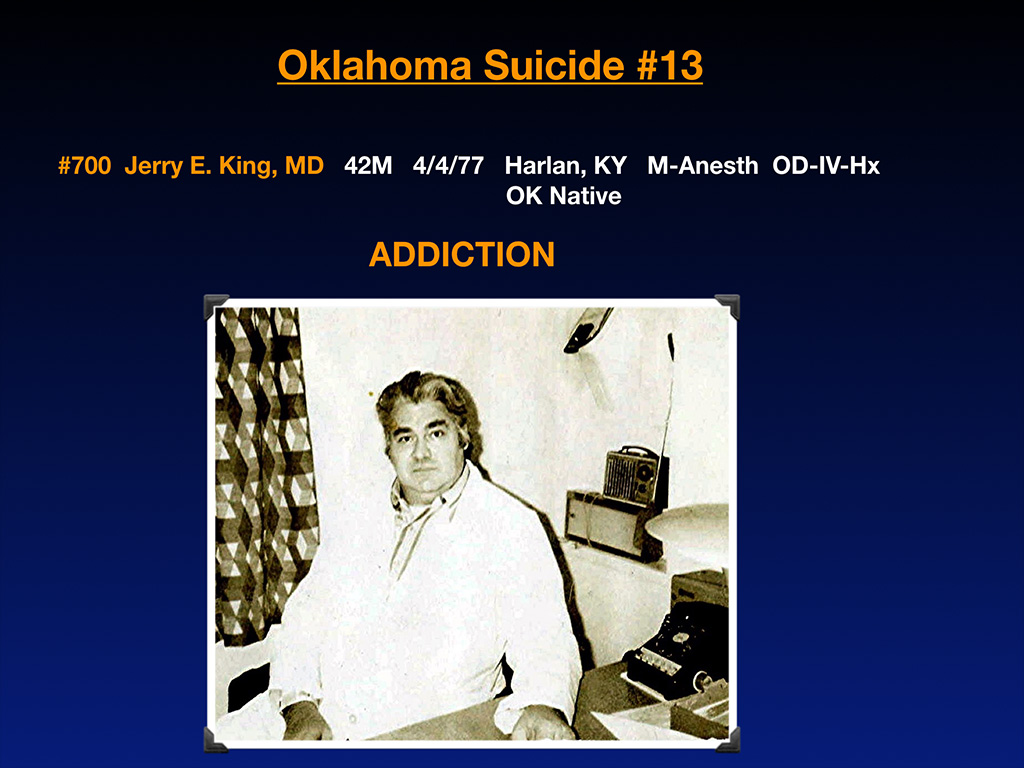

Meet René. She gave me a letter to read to physicians when I spoke last week at the Oklahoma Osteopathic Association. (Listen to keynote here). Here’s what I shared from this courageous woman with a wise message for us all. My talk was dedicated to her father, Jerry E, King, MD, and all the medical students and physicians who lost their lives to suicide in the pursuit of helping and healing others. See Oklahoma doctor suicides—13 reasons why.

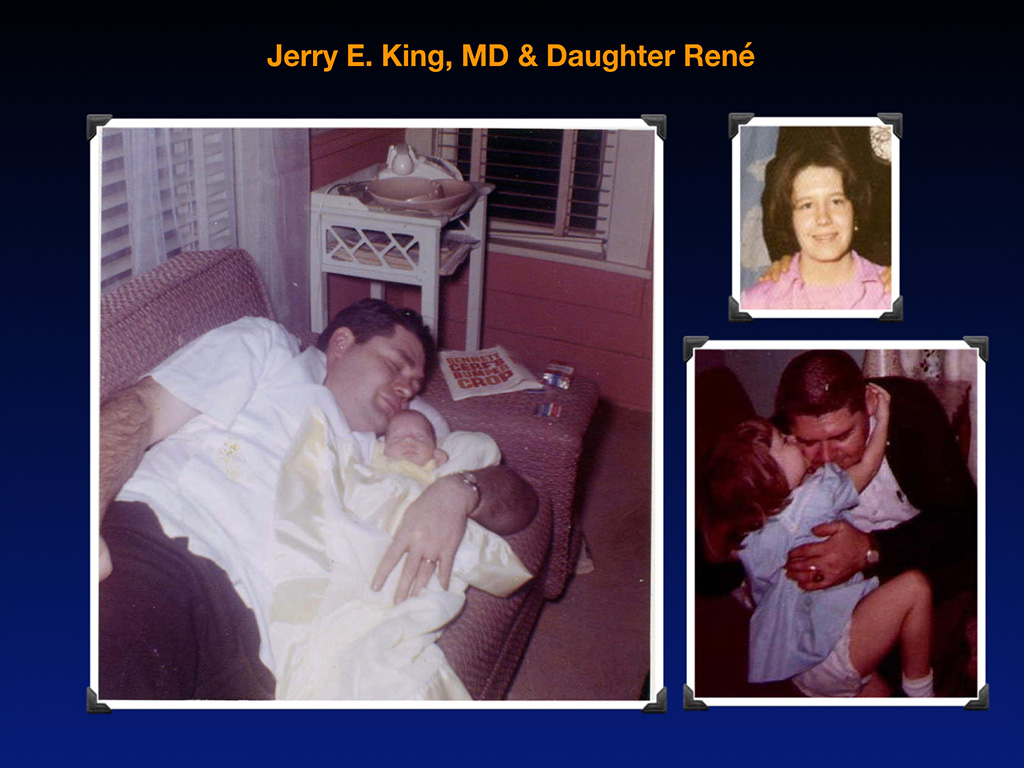

I have a letter from Jerry’s daughter I’m going to read. Here’s his daughter in his arms after her birth, his daughter hugging him as a toddler. And there we’ve got her at 14 years old. This is a letter from her. She’s in her 50s now. She wants me to read this to you.

“My father was from a poor family in Oklahoma and the first to go to college. He father didn’t even make it to high school. Dad graduated from the University of Oklahoma Medical School and became an anesthesiologist in 1964. He was on the first team to successfully reattach an amputated arm. The surgery went so well that the patient became a pottery artist. I have one of the pieces in my home. Unfortunately, during that time that he went through residency, it was not uncommon [as I know many of you recall] for drug companies to send samples to med students, residents and doctors. It was at that time that my father became addicted to uppers and downers in order to make it through the long hours. In his mind, the drugs helped him accomplish his dream. But in the end, they also took it away. Many times over his career, he was caught using drugs, and his fellow doctors and the administrators would hush it up and move him to another town in another hospital out of some twisted combination of loyalty and shame.

Thing was, my father was excellent at what he did, a gifted physician, wonderful teacher. Hospitals and universities were glad to have him at first. And then the meds would start missing, and patients that needn’t had died, did. After he got caught in Lexington at Saint Joseph’s hospital, while he taught at the University of Kentucky, they took away his drug license. He then found a job in Harlan Country, Kentucky at the Harlan Appalachian Hospital, where somehow he was able to not only teach but once again be in surgery. Don’t ask me how they allowed an anesthesiologist without a drug license to be involved in surgeries, but they did for a year. But this time when he got caught after meds were missing, and a woman died, he was told that they would have his medical license pulled. He went into work that Sunday morning and, according to the coroner, went into the surgical dressing room and shot himself up with enough medication to kill 20 men his size. One of his students found him. I still remember them coming to my house.”

She was 14 at the time. See the picture of her? That’s how old she was when this all took place, okay? So just listen to what this child went through. And we (the medical profession) have set this situation up this way so that she had to go through this. René explains that they came to her house. She said she can’t ever forget this moment. They lived up on a hill. It’s impossible to get there. When there are five cars in the driveway (only two fit in the driveway and three are on the lawn) and there’s all male doctors in the house and administrators surrounding her mom when René walked into her house. The first thing her mother said, “Well at least we have the memories.”

“My mother, who had been an active alcoholic for a number of years, was incapacitated and had no memory for six months. At 14 I had to notify my grandmother in Oklahoma of her son’s death and arrange my father’s funeral. I still have the canceled checks, where the local banker, who knew the situation, allowed me to sign in my childish scrawl the check for my father’s casket. Chemical dependency among medical personnel has to be addressed, whether it is the stress of the addiction or the repercussions of the addiction, patient deaths, loss of family, loss of license, law suits. Chemical dependency plays a serious part in physician suicide. If we don’t better communicate the issues of chemical dependency with premed students and rid the profession of the enabling of fellow staff and administrators and eradicate the shame of dealing with addiction, we will continue to lose patients and medical personnel. I know all too well how deadly that silence can be.”

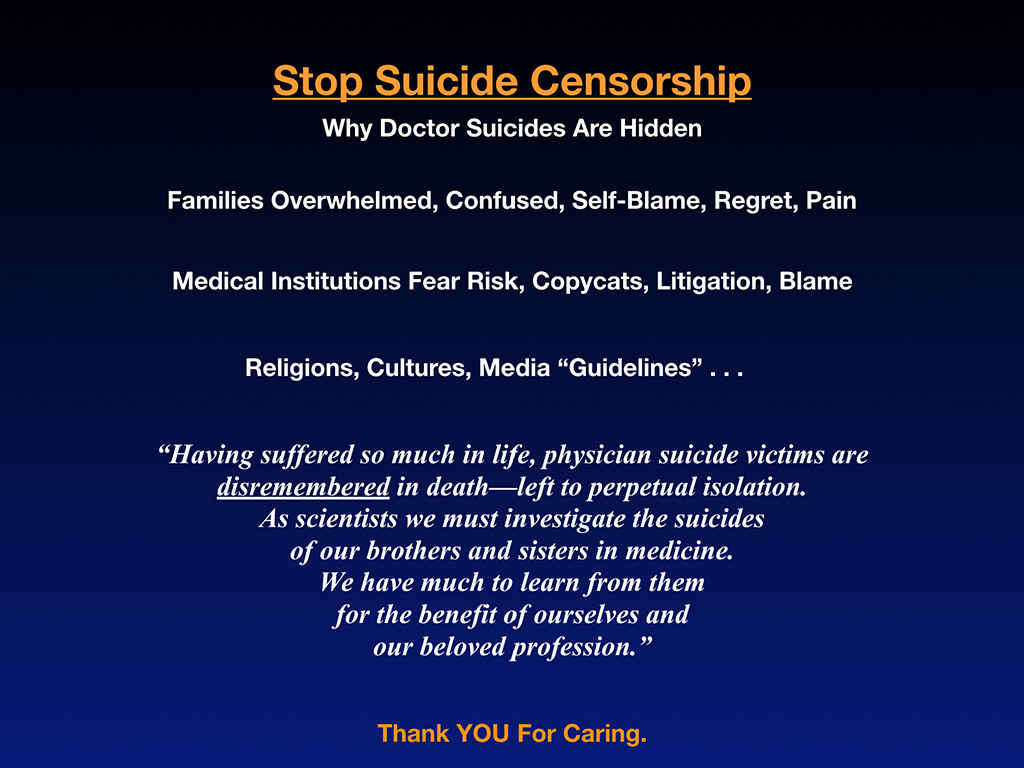

So I am here to please beg you to help me stop the censorship around suicide and especially medical student and physician suicide. If we’re going to be of any use to veterans and everyone else that’s dying of suicide (including all the patients who need us to be in our right mind when caring for them), we—the medical profession—must set the gold standard for how to handle mental health and deal with suicide.

Doctor suicides are hidden by other doctors and by families and medical institutions and the media . . . Here’s why they’re hidden. Well, the families are overwhelmed, confused. They’re blaming themselves. They have all sorts of regret and pain. You cannot leave it to a family in deep grieving, who just lost their star child or their husband in the prime of their career to deal with this. How are they going to deal with this? They’re crying in bed. They’re incapacitated for six months with alcoholism. They can’t deal with this.

Medical institutions that could deal with this are too worried about CYA for risk, copycats, litigation. They’re worried about being blamed, so they don’t want to do anything about it, because it’s like bad PR. You don’t want to be known as the hospital with the highest number of doctors and residents jumping from the rooftops. Now if the family doesn’t want to deal with it, because they can’t, and the hospital won’t deal with it, but that’s what they should be doing, if they really are, like the billboard says in town, providing the most compassionate care, then what?

Religions don’t want to deal with it and suggest that you’re burning in hell. That’s not popular either, cultures, people trying to preserve their reputations in the aftermath. And then we’ve got the final nail in the coffin—suicide media guidelines, which I can’t stand, because they handle suicide differently than beheadings, kidnapping. Everything else is on the front page of the news. There are murders, rapes, everything else—except suicide. We’re adults, and we’re reading about the true facts of what’s going on in the world. But suicide is not reported like everything else, because you’re not allowed, because you’re not allowed.

We’re adults. We’re scientists. Isn’t it time to be allowed to talk about suicide? As medical professionals when will we be able to review these cases? We’re not going to solve this epidemic if we don’t talk about it and continue to allow all this censorship.

Please help break the silence, secrecy, and shame the allows others to lie and censor the cause of death of our doctors. Doctor suicide is an epidemic—a public health crisis. One million American are losing their doctors to suicide annually. We require a public health response. We must stop hiding the truth. Stop lying on death certificates. Stop turning our heads away and allowing doctors to suffer in silence. Stop ignoring and enabling the sickness and the pain carried by our doctors daily. We carry a huge burden. We’re surrounded by death and suffering every day. Let’s get real.

As adults—scientists and—we must protect each other and the public by not allowing one more doctor suicide to be buried in shame—left to a grieving child to make sense of adults who censor the truth.

Censorship has never solved a public health crisis.

Thank you.

We need to change our healthcare. It is so sad ?

Sad. I have twin girls who are 14. They would have been 11 if I had successfully completed suicide. I can’t imagine what this young girl went through. If the censorship we see today is any indication. Imagine what she went through.