Surgeons are not Navy SEALs and should not be trained or treated like frontline special forces.

We must remember surgeon burnout when we are addressing health worker burnout. Surgeons suffer burnout more than most other medical specialties.

I’m Dr. Pamela Wible and I run a free doctor suicide helpline. I hear from physicians from all specialties—including surgeons. Doctors tend to minimize their suffering by using terms like “stress” and “burnout.”

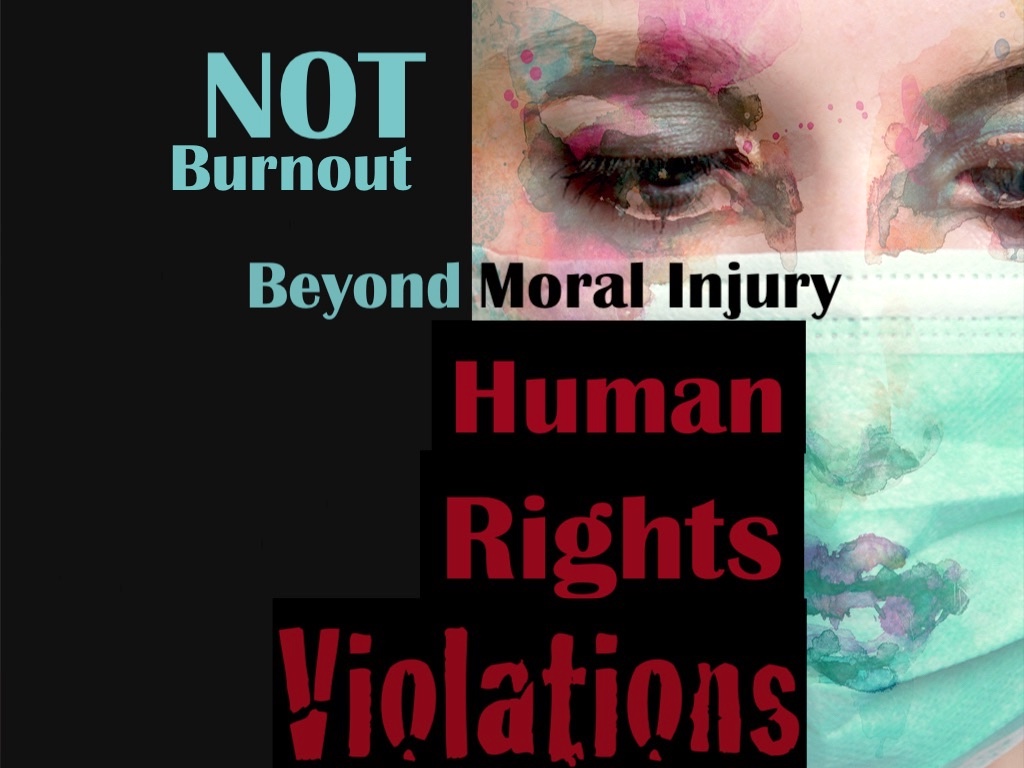

First, I want to point out that referring to stress caused by an abusive workplace as “physician burnout” is offensive—and covers up what amounts to human rights violations in medicine. Instead of talking about doctors being burned out, we should focus on workplace abuse that leads to real mental health diagnoses—depression, anxiety, PTSD—even passive and active suicidal thoughts.

Yet while I strongly disagree with the use of the term physician burnout, I will use it here, because it is a term we are familiar with. In fact, for the last forty years large healthcare corporations, residency training programs, and medical boards have loved talking about how they are going to fix doctor burnout. Yet doctors are faring worse than ever. Why?

Healthcare institutions are complicit in causing the burnout problem, yet now, they want to help. They want to seek out which cogs in the machine are broken, so they can be discarded. They have no real interest in helping. Though they have figured out how to make money from burnout workshops and “forced wellness” activities.

Here’s how medical institutions use the word burnout to blame doctors for hazardous working conditions:

Residency programs push their physicians in training to the breaking point. They are overworked until they suffer from emotional exhaustion and physical exhaustion. Some even attempt suicide or die by suicide.

Read more on how to prevent surgeon burnout, medical mistakes, and even suicide . . .

Surgeon burnout is particularly a major problem, because surgeons are under a huge amount of stress, more so than many other physician specialties. And, because of concerns about patient safety, surgeons are under a higher level of scrutiny.

Do surgical residents suffer from workplace-induced stress and depression?

Surgical residents spend at least six years in training after med school to become general surgeons or specialized surgeons. The organizational culture of a surgical residency does not favor the mental health of its residents.

Some residency directors may, in fact, see the high-stress environment as a way of weeding out the unfit. They think they will get the best surgeons by eliminating the residents who cannot work under intense pressure, without sleep, and for incredibly long shifts.

Navy SEALs are pushed through incredibly stressful training. The purpose is to weed out the weaklings and select the strong who can perform optimally in any situation.

It makes sense to train the top specialists in the military in this manner. They have no idea what they will be up against in the field.

A Navy SEAL member may be kept awake for days on end, and they may be suddenly attacked. Enduring a surprise attack, under fire, with no sleep is incredibly difficult. The best candidates for the job are burnout-resistant people.

Many medical students and doctors have told me they were less stressed during sniper fire in war-torn countries than medical training.

Medical student explains how she was less stressed in Afghanistan.

Surgeons and surgical residents are civilians who have qualified to study or practice surgery. Of course, putting them in impossibly stressful situations can lead to depression and emotional breakdowns. People who are best suited to be surgeons are not necessarily burnout-resistant.

Who decided that a doctor should be treated the same as a Navy SEAL?

Did you know that Osama bin Laden was not supposed to be killed during the Navy SEAL raid in Pakistan? The intention was to bring him back alive.

So why did the mission plan change at the last moment? The enemy forces were shooting at the SEALs as they attempted to capture Bin Laden. They had to think fast, as deadly bullets showered over their heads and all around them.

A surgeon’s job is very different from a Navy SEAL, yet both must develop refined technical skills that may take years to master. The difference is that a surgeon can expect that most parameters of their work will remain stable and unchanged.

Surgeons do not have bullets flying overhead while they are performing surgery, and they are not operating in unfamiliar territory. There is enough to worry about with the surgical case itself without having to think about outside stressors.

Yet, for some reason, surgical residents, and practicing surgeons are put under incredible pressure, with long shifts, excessive patient loads, and demands from administrators and staff. While the hospital and operating room are not a war zone, after being awake for over 24 hours and being thrown into the operating room one more time, it can start to feel like one. Being a surgical resident can feel like a losing battle.

Here is a video I made—a brief history of surgical training:

Will we still get great surgeons if we go easier on surgical residents?

How would you feel about a war veteran with PTSD driving your children in a school bus? Every time there is a sudden loud noise on the road, the poor bus driver thinks he is back on the battlefield. How will he react at the wheel with a bus full of kids behind him?

Would you feel comfortable having a surgeon with PTSD performing your surgery? The fact is that many surgeons, maybe even most, have experienced trauma as a part of their training, and they already have PTSD.

Why do surgeons sometimes seem irritable when family members ask too many questions? In residency doctors-in-training get pimped with tough questions.

Pimping is the act of a supervising doctor, or an attending, asking difficult medical questions of residents or students. The purpose is to terrify and intimidate as much as it is to assess learning and knowledge.

In fact, pimping is more about intimidation and emotional abuse than it is about education. In addition to pimping, surgical residents are overwhelmed with patient loads, surgical cases, and extreme long hours.

Sometimes, surgical residents are awake for days, struggling to go just a few more hours, using an endless supply of chalky, bitter hospital coffee to keep going. If you know someone who has gone off to surgical residency, you know the battle-fatigued look they have after a while.

They go in cheerfully, thinking they will be the first resident to handle it all without getting overwhelmed. Then, a few weeks in, they are disheveled with bags under their eyes. They have a look as if someone had just smacked them over the head with a baseball bat.

What if residency directors did not torture their residents?

Instead of the bootcamp surgical residencies that have been the standard for many decades, what if we didn’t treat residents as if they were special forces going into a war zone? What if we focused on teaching surgical technique and surgical medicine without torture?

Many practicing doctors see the torture of residency as a rite of passage. They really do see it as being like Navy SEAL training.

Only the strong survive. But what if those who don’t survive surgical residency would have had the potential to be great surgeons?

What if selecting for the top surgical residents who can stay awake for several days straight and walk through the hospital halls like the walking dead is not the best way to produce top surgeons? It might seem like revolutionary thinking, but it is possible that we are approaching surgical training all wrong.

When you buy a new car, do you want your car tested off-road before it is delivered to you? What if the dealership told you they drove your car up a mountain, over rocks, and through a mud pit? They just wanted to make sure you get a car that can handle tough terrain.

You would be outraged, thinking that they just shortened the life of your car, and they probably introduced some subtle problems that will arise along the way when you go driving. The car proved itself in extreme conditions, but it may never drive the same again.

We can do better.

Let us focus on the science of learning and the science of teaching. Let’s allow surgeons to work in the same way that top coders are treated at big tech companies.

Tech companies want their best programmers to be comfortable and treated with respect, so they can enter “the zone.” When a programmer is in the zone, they are applying their knowledge and experience effortlessly and creating powerful software with the finesse of a concert violinist.

The best surgeons work this way as well. There are surgeons who perform surgery as an art form, while a captive audience of nurses and students look on.

With better treatment of residents, we will likely discover more great surgical artists who are capable of saving many lives with their exquisite techniques. How many great surgeons have been squashed by residency?

How many surgeons who could have been better surgeons, and better spouses and parents, go through life with the scars of emotional trauma carried from residency? We need more surgeons, and we need to protect our surgeons in training.

Let us practice harm reduction in surgical residencies. While it would be best to do no harm, let us start by doing less harm by treating our surgical residents like human beings, who are allowed to sleep, allowed to use the bathroom, and allowed to learn without fear.

I can guarantee that treating surgical residents humanely will result in residencies producing better surgeons. And, we can all sleep better, knowing that these important human beings who are working towards a career of saving lives will be treated with the respect they deserve. For more help, contact free physician helpline.