Christine Sinsky, M.D., from the American Medical Association interviews Pamela Wible, M.D., after her TEDMED talk. Watch periscope video here. Fully transcribed below:

Dr. Sinsky: This afternoon we’re here in Palm Springs, and I’m delighted to be here with Dr. Pamela Wible who gave a terrific TED talk last night. I’m Dr. Christine Sinsky, the Vice President of Professional Satisfaction at the AMA, and we’re here at TEDMED because it’s an important gathering of deep thinkers, of innovators, of practicing physicians. The AMA believes in bringing those key constituencies together. So Pamela, you really knocked it out of the park last night with your talk. It was really just terrific.

Dr. Wible: Thank you so much. It was really fun, amazingly fun to present a topic that’s so challenging.

Dr. Sinsky: I wanted to start out by telling you one of the things that is meaningful to me. That care of the patient requires care of the provider, and I could feel your passion last night around our need to be better as a medical community at caring for each other, at caring for our colleagues. I wonder if you’d like to start from there and move forward.

Dr. Wible: I think we really need more of a culture that is collegial and like a family, instead of a culture of competition. And that starts during premed and day one of medical school we could set the stage for more of a family atmosphere where we’re looking after each other like you would family members. I think that’s how it works in other high-stress professions like fire departments and police departments. People are really there for one another as supports.

Dr. Sinsky: So shoulder to shoulder, together. Picture for me, you are the Dean of a medical school. You have the ability to help change that culture. What would you do?

Dr. Wible: Day one of medical school I would introduce the students to the campus and welcome them home. This is where you will be with your family for the next four years. You’ve jumped through enough hoops to get here and we are here to support you. I would give my personal cell phone number to the students. I would have a panel discussion with some of our top leaders at the medical school who would share their personal struggles with despair and then triumph from professional liability cases, from deaths of their patients, from divorce, suicidal thinking and all of this so that we normalize the conversation of our human needs. And we can start to bond with each other beyond just the supratentorial lectures and multiple-choice tests.

Dr. Sinsky: You know, I was talking after your talk with one of my physician colleagues and we were thinking about how we each felt in medical school and some of that impostor syndrome that I think all physicians feel—that we are isolated and alone and no one else is feeling that way. Tell me more how this approach when you are the Dean can help to address that issue.

Dr. Wible: Right now students feel extremely isolated and that just continues through our entire profession. We are in a culture that glorifies self neglect. And so we end up working on our little islands and we don’t ask for help because, of course, we are supposed to be the helpers. We are not supposed to be receiving help. And so if we can just break through this and really look after one another. Create a situation in which people do not feel individually defective. Once we can communicate that you cried yourself to sleep after the stillborn and so did I and we had the same reaction to that case, it just normalizes our human experience. And that’s what we need to do is start to have conversations like real people, like we are now without the stiff starched white coat.

Dr. Sinsky: Right. And the isolation behind the strong man kind of front. So last night you really spoke very much from the heart, about the extreme when we don’t care for each other. The stresses and lack of support can manifest in the most severe outcome—death by suicide. Can you talk a little bit about why that’s important and the extent of it, and move to solutions, things that we as a medical community can do to help our colleagues in pain.

Dr. Wible: It’s important because we are losing an entire medical school full of physicians every year to suicide, so hundreds of doctors. Both men I dated in medical school died by suicide. In my small town we lost 8 physicians to suicide, 3 within 18 months. So it’s a huge public health issue. More than one million Americans lose their physicians to suicide every year so we must take this seriously. If not for the individual, the public health implications of losing that many physicians when we already have a physician shortage. Right? So that’s one thing. What was the second part of the question?

Dr. Sinsky: I just want to clarify that a full medical school every year.

Dr. Wible: Yes. And that’s not even counting the medical students that die by suicide. And what disturbs me is we are not tracking any of this and we could be tracking it because we know all the names of currently enrolled medical students and physicians in this country, so it shouldn’t be a mystery. We should have firm numbers. Some of this is not being tracked properly.

Dr. Sinsky: So who is doing it well? Who is addressing suicide prevention at the medical school level well? Or at the practicing physician level well? And if no one is what should we be doing?

Dr. Wible: Some schools like Saint Louis University and others are doing a pass-fail grading system so there is not the tension about grades that creates that competitive environment. So if we just take the pressure off of these amazing people. Medical students are already in the top 1% of compassion, intelligence, and resilience in the country. How much more pressure do we need to put on these high-achieving people? Take the pressure off and let them enjoy the love of learning instead of just shoving all these multiple-choice tests that never end with medical minutiae that they are not going to use in the future. So take the pressure off and create an environment where there is peer networking and peer support groups. Schools should have a suicide helpline that the students man themselves. We learn to take blood pressure on each other. We are using each others’ bodies to learn how to do the physical exam. Why not let these medical students in their first and second year learn some of these skills to help each other emotionally? Have them on call from first and second year so they feel like they are doing something other than just reading their books. Actually helping each other.

Dr. Sinsky: So you are getting at one of those issues that makes physician suicide such a challenging problem and that is for physicians there are barriers to getting mental health care and that probably starts in medical school. Getting mental health care from your boss or supervisors might be an issue and once we’re in practice. So what else can we do to reduce the barriers to getting help when we need professional help for depression that’s extreme, for example.

Dr. Wible: Well, one thing that I discovered when people call me is that medical students and physicians who do have extreme depression, anxiety, panic attacks that are occupationally induced were normal before medical school. Just listening to them on the phone helps. I am not giving them drugs. I am not their doctor. I’m just a friendly colleague on the phone. They feel so much better afterwards. I continue to drive home the point that you’re not individually defective. This is a system defect. If more than 50% of a group of people develop a condition we call “burnout”—which is really a victim-blaming term—then it is really a system’s issue, not an individual issue. Once they realize that they are not individually defective, they feel so liberated and they feel so understood. We should not wait until people are so far gone into psychotic depression that they need to go to a psychiatrist. The first day of medical school and as an ongoing continuum of care we can really listen to each other and be human with one another.

Dr. Sinsky: I want to make sure I caught this because I think this is a hugely important point. We need to think about the locus of responsibility for physician distress, for physician suicide, for burnout (if we use that term) in the external environment much more so that in the internal environment as a defect in the strength or the ability of that person. Did I understand you?

Dr. Wible: Yes. It is a bigger issue. It is not that the an individual was born with a resilience deficiency. You’re in the top 1% of resilience if you are in medical school so let’s honor your strength and capacity for learning and providing care for people. And one thing that I wanted to say since I think this is about creating your ideal clinic is that we should really teach to the personal statement, not just to all these multiple choice tests. People come in with a clear indication of what their soul’s purpose is and what their intention is and what they’d like to receive for their $300,000 of tuition and schools need to be teaching to these personal statements and digging them out of the file drawers and asking the students, “How are we doing getting you to your goals here? Are we doing well as a school?” There’s really only 2 types of practices that have emerged: relationship-driven or production-driven practices. What medical school seem to be doing now is driving everyone into assembly-line, production-driven practices which do not match what most people have written on their personal statements. So we need to go back and ask the students, “How are we doing? How can we do better?” and really help people live their dreams—because that IS the ultimate solution to suicide. When you are living your soul’s purpose, there’s no way that you want to take your life. It’s when you feel that’s been stolen from you [that life loses meaning].

Dr. Sinsky: So I want to ask the last question. What do you think organizations like your organization, the American Academy of Family Physicians, or the America College of Physicians, or the AMA can do to help reduce physician stress, reduce the risk of burnout, reduce the risk of suicide, and increase the likelihood that we’re practicing in an ideal practice?

Dr. Wible: I like to reference Maslow’s Hierarchies of Needs. During medical school you are thrown down to the lowest rung of physiologic instability (not getting to eat, sleep, and all that stuff). What Maslow did is he studied people who were high achievers who were self-actualized and that’s what we should do in medicine. Instead of talking about all the doom and gloom, start showcasing that doctors who have figured it out. Let’s have a panel of the happiest doctors in America so we can hear what they are doing and why they are so happy. Doctor means teacher. Medicine is an apprenticeship profession. We learn by modeling other people. So let’s start showcasing the people who are really having a good time, who’s patients love them, who are just really rocking it in medicine and that would be a really great way to learn how to do it right.

Dr. Sinsky: So this is not a set-up Pamela. You may not know, but part of the work we’re doing at the AMA is exactly that.

Dr. Wible: I really didn’t know that.

Dr. Sinsky: You didn’t know that. I guess we’ll close with this. We have put online a series of practice transformation resources to help to get back to our calling of relationship-based care. So that our physicians can spend the majority of their time on work that only physicians can do, relationship-building, and medical decision making. And they are all about creating an ideal work environment.

Dr. Wible: That’s lovely. That’s really great. I’m looking forward to seeing that.

Dr. Sinsky: Maybe we will call you in to be one of our authors. We also highlight places where people are doing a very good job. So, Pamela, I’d like to thank you so much. You’ve really inspired many, many people across the country with the work that you’ve been doing and the message you’ve been articulating.

Dr. Wible: Thank you so much. It is a joy to be here.

* * *

Dr. Wible’s TEDMED talk was featured in the Palm Springs newspaper the following morning. Article here with great photo! When her TEDMED talk is released online, it will be posted here. Hopefully soon 🙂

Hi Pamela

I’m finally able to understand your joke about the “supratentorial lectures” 🙂

Unfortunately, now that I’m neck deep in school (mini med school with a pared-down curriculum) I’m also beginning to understand this issue of depersonalized, competitive medical training. To give some context, I have already been through graduate school. While grad school was challenging, I was also supported by colleagues and peers, and was encouraged to challenge the status quo and to think outside the box. You are right, medical training is different…it’s designed to produce automatons. Cogs in a wheel of “efficient” and “evidence-based” care. There are nods to this “personal and human” side of medicine, but these are just nods–words on a power point–and nothing more. I’ve been really disappointed. I watch my fellow students try to speak up in class about structural issues in medical care, and see their delightful comments get smashed down in the interest of time. One of the students in our class has an MPH…she’s got so many insights into the social determinants of health. I’ve got another classmate who’s a physician from overseas and has practiced medicine for 10 years in rural settings. These people are amazing and we could listen and learn from them, but there’s “not enough time” to do anything but stare at power point presentations about how to protect ourselves from law suits. There’s never time or space to discuss feelings or reactions or personal experiences…it’s not a classroom, it’s a factory.

Thank you Erica for speaking up. Time for us to have this conversation about the failure of the current medical education model that is failing to deliver the absolutely AMAZING brilliant and loving physicians, NPs, PAs that patients deserve. It is an assault on our humanity and together we can change this culture. Please continue to speak and write about what matters.You are a beacon of light of others who are afraid to do so.

Great interview! You so rock! ??

Thanks Bodhi!

Very amazing interview.

A very big Thanks to you Dr. Wible.

So thrilled that I could inspire you 🙂

Your commitment, passion and “spiritually based” attitude and mission is greatly inspiring. This is a revolution and an important one. Thank-you for all that you do, for your strength of character, and loving compassion. I continue to look forward to more changes and improvement as time goes on. Again, Thank you!

An absoute labor of love. It is 100% my honor to devote my life to our noble and beloved profession.

OK. Where is my T-shirt that lists my hero (heroine). Defined as: a person … who is admired or idealized for courage, outstanding achievements, or noble qualities.

Oh, let me know. I’ll buy one for my mom.

Courage just means leading with on’e heart. Anyone can do it.

Pamela, I continue to be impressed by your intestinal fortitude. You have experienced pain that would have stopped many people in their tracks or changed them for the worse. Instead of allowing that to happen, you used that pain to forge an iron will to fight for much needed change in medical education, and in the medical profession itself. You are helping create a future with healthier and happier doctors who, of course, will produce better clinical outcomes and have healthier and happier patients. The importance of this cannot be understated. We need to be able to depend on one another and trust one another. The stakes are simply too high. The lives of patients and the lives of physicians are on the line.

Your statement about collegiality in other high-stress professions like fire fighting and law enforcement is spot on. I know that because I have experienced it firsthand. This is in stark contrast to what I have experienced as a doctor. At various times during my medical training and even in my medical career I found myself at the receiving end of abuse by the hands of physicians produced by our dysfunctional medical education system. Sadly, I have seen some of them self-destruct and completely lose their lives or their careers. Against all odds, some doctors such as yourself have become leaders in the medical profession, setting an example for others to follow and becoming a positive force for change. The majority of us become privately disillusioned in one way or another, some more so than others; and many progress to the point of being downright despondent.

That’s where I was when I graduated from residency training. I was a despondent former resident who had just become a despondent attending physician. I had become so disillusioned that the majority of time I spent searching for jobs as a senior resident was spent trying to find a job outside of the patient care sector altogether. Although I found this to be a difficult task, that process led me to discover that I was particularly well suited for work in the criminal justice sector. It only took me one year to take the plunge and enter the police academy. This was a full time endeavor that required a big commitment on my part. Many people I knew stared in disbelief as I did this, some even questioning my sanity. But I did it nonetheless, and I actually found it to be a much needed break from cookie cutter assembly line medicine. Once I graduated from the police academy, I started working as a reserve officer with a local sheriff’s office and quickly found that I had become a member of a very large extended family of officers who, barring criminal or unethical conduct on my part, were willing to stand behind me through anything. That trust and respect was present on or off the job. I quickly found myself investigating prescription drug crimes and, after only two years, I put up my stethoscope and began working as a full-time paid narcotics officer. The job was demanding as well as stressful. I was expected to willingly go into some extremely dangerous situations because it was my job to do so. But I always knew somebody had my back. I never experienced that level of camaraderie in the medical profession, where I often had to watch my back. That experience left an indelible impression on me and changed me for the better, ultimately leading to me becoming a much more compassionate and effective physician. I love being a doctor now because I love what I do. Patient care means so much more to me now than it did when I was just finishing residency. I still have to deal with some of the dysfunctional products of our medical education system, however. But I now see these people with more compassionate eyes. They are damaged souls. Like me, they entered medical school with bright eyes and enthusiasm only to be inhumanely processed, packaged, and sent out the other end to be chewed up yet again by a residency program. When they were finally spit out the other end of the residency program, they had become something unrecognizable compared to what they were before they entered medical school.

If we do not do something about this problem now we are going to lose some of our best and brightest minds to other professions. And the cycle of abuse and occupationally induced mental illness will continue, jeopardizing the safety of healthcare professionals and patients alike. The status quo is simply unacceptable now.

Thank you Colin for sharing your story. Validates and reinforces my hypothesis that we need to behave more like comrades that competitors for the good of all involved. I’m always told to “keep up the good fight.” I’ve never considered my work a fight. This is a labor of love for a profession that I absolutely adore. As a healer, I can not remain silent when I witness the wounding of my colleagues by a system that seems to not understand what it is doing. The good news: a change in heart and a mind shift can revitalize our profession. One doctor at a time. Doesn’t even really cost money. Love is free.

Yes it is, and I consider it an honor to stand with you as a voice against educationally sanctioned abuse. As more of us are willing to publicly speak out against these practices, many more will join us. All of us know it is wrong, but most of us have been too scared to speak up…until now. It is medicine’s dirty little secret.

Thank you for speaking on this tough issue. You are a bright shining light.

Labor of love. Please also share your thoughts here (story is trending) http://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2015/11/we-lose-a-medical-school-full-of-physicians-every-year-to-suicide-an-interview-with-dr-pamela-wible.html

Pamela,

Great interview! And congratulations for knocking it out of the park!

Haven’t gotten to access the talk yet and hope AMA and TED-MED will find a way to get it out there publicly soon.

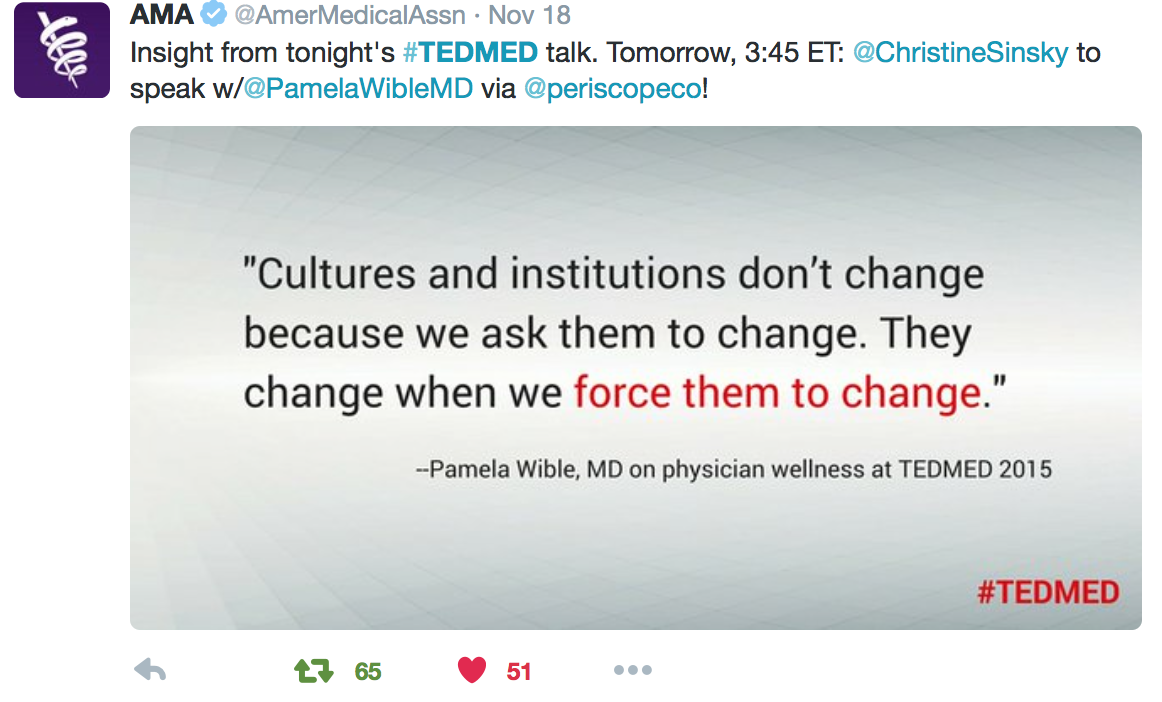

Your referenced quote, presumably highlighted (ironically) by people at AMA, is so poignant: “Cultures and institutions don’t change because we ask them to change. They change because we force them to change.” As docs, we’re afraid of giving pushback, perhaps because there’s such a sense of futility, or maybe fear of reprisal, or perhaps it’s just not in our “healer / collaborator” nature.

Thank you for being right at the forefront of confronting the epidemic of demoralization, despair and suicide in medicine today. Rather than pathologizing it as so many academics are prone to do, droning on with risk factors for depression and arguing that the doctor must’ve been somehow deficient, you’ve approached the crisis from both a compassionate non-pathologizing human standpoint and a straightforward systems framework. With increasing stress and dysfunction in the healthcare system (as with any system), there is bound to be a corresponding rise is the incidence of dissatisfaction, dysphoria and waning performance. And with that sadly comes a desire to flee the profession and leave all of one’s hard work behind.

We’ve come to a point where it’s mandatory to speak up to the insanity that medicine has become – for the well-being of our patients as well as our profession.

With combined voices, hopefully we’ll force cultural and institutional change toward depression and other psychological illnesses. Most especially, we need safe and utmost confidential resources – well trained and approachable, likable and trustworthy, for physicians, residents and med students to see that provide genuine help instead of the current institutional structures, some of which contribute to marginalizing, humiliating and downright harming a physician and jeopardizing his/her career.

RE; AMA Interview

To Tamara: Change is difficult, especially in the still patriarchal field of medicine but is nonetheless inevitable. But change is a process which starts by

1. Identifying a critically important problem (physician suicide)

2. Understanding its roots (arch-conservative culture compounded by Big Box Greed)

3. Connecting with peers to gather further momentum and

4. Communicating to all the urgent need to change with powerfully articulated truths “We lose a medical school full of physicians every year to suicide”.

Dr. Wible was able to do all of the above and bring this terrible issue to the forefront, effectively and repeatedly, a testimony not only to her leadership but to the fact that change is coming.

That Dr. Wible was invited to publicly discuss this grievous (yet taboo) loss, by the AMA no less, and to speak truth to authority (the AMA) is nothing short of astonishing “Cultures and institutions don’t change because we ask them to change. They change when we force them to change”.

Change can be further accelerated if 5% of us were to contribute towards Dr. Wible’s efforts and I take this opportunity to urge each one of us to share her message as widely as possible (colleagues, coworkers, friends and families, etc.).

Elias

In response to Tamara: Tamara • a day ago

I just wanted to respond to what Pamela said below about “being the change.” I thought that was what I was doing when I changed careers to enter medicine. Medical school seemed to reaffirm that decision, yet somehow we were still shielded from the reality of the medical culture as it is now: charting through meals; downplaying all the work done from home; assuming that no one else is struggling to keep it all together and move fast enough through clinic; trying to forget what it was like in the “real” world with breaks and employee satisfaction… It’s often hard to remember why I got into this and what it was I thought I could change, but then my patients and conversations like this one remind me no one is satisfied with this system. I’m still so inspired by the ideas I’ve heard about potential solutions. Yet if we keep pushing patients and their physicians through the same system, how many of us will have the energy to fix it?

I find this conversation so interesting. I am aware of the physician suicide rate in the US, at least to the degree that these deaths are tracked and reported. It is my opinion that the root cause of so many of our medical students, residents and practicing physicians choosing to end their life extends well beyond the old school patriarchal system of training. It is simplistic to believe that this epidemic can be stemmed by having a medical school dean put themselves on call to the students, create a family atmosphere or present to them various scenarios by those physicians who have found a way to balance their professional with a personal life.

This approach is condescending and naïve.

I have practiced primary and urgent care medicine since 1998, with a 2 year administrative role as the state clinical coordinator for the Mississippi quality improvement organization, IQH, 2006-2008. I have watched the government’s plan for improved quality of health care unfold- initiated prior to President Obama’s first administration- with the mandated adoption of electronic health records, and the multitude of ‘quality measures’ for reporting to CMS. Not to mention the ridiculous ICD-10 codes… have you seen these? Absurd. Busy work. -All in the name of quality improvement of care and safety for patients with cost savings…

The Department of Health and Human Services under Secretary Leavitt at the direction of President Bush established the American Health Information Committee composed of the private corporate stakeholders who would benefit from our current system. The health care laws to do not improve quality of care or guard patient safety or privacy. It is my opinion that physicians and patients have become a disposable commodity, collateral damage, as the corporate employers, insurance and pharmaceutical companies solidify their future holdings and profits- under the guise of quality and safety, and threat of HIPAA laws- do you know what a Business Associate Agreement is? Read the law.

A representative of ARHC said to me directly that HHS holds the practice of medicine to be a “cottage industry” and that physicians should not be allowed to simply do whatever they think is right for patients, that all patients should get the same care. She was advocating for the electronic medical record and virtual care- because computers do not make mistakes.

Physicians accept the academic and financial responsibility demanded of them for the opportunity to practice medicine, even when it means there is no time or personal capacity at the end of the day to sustain themselves, much less nurture relationships. We sacrifice greater than a decade of our lives, loss of income and accept the minimal resident salary and interest-accruing massive debt to become physicians and continue to meet the lifetime of ongoing requirements for board certification, licensure and employment… because, it is required to practice medicine… right??

Well, I wonder about something. If it takes a medical degree to practice medicine, then why are patients seeing physician assistants and nurse practitioners in primary care and specialty clinics instead of a physician?

A student can complete nursing school and enter an ARNP program without nursing experience, even enter a Doctor of Nursing program without ARNP experience. They graduate and have primary responsibility for patient care… as Doctor nurses. I know this is true because I have worked with them in recent years.

Physician assistants are licensed to diagnose and treat patients after completing 12 months of didactic training and 12 months of clinical rotations. The supervising physicians are not required to be on site- the PA’s practice independently and a selection of charts are reviewed after the fact.

Doctors are competing with the mid-level providers for employment.

A ‘provider’ is seen as the same as a ‘physician’ by patients, and is frequently referred to by the patient as ‘their doctor’, especially if the provider is male.

We rarely get to work with a nurse, as they are being replaced more and more by medical assistants.

Doctors are pressured to see quotas of higher patient volumes per day by their employers and are now withholding salaries based on the patient satisfaction surveys. Doctors rarely have any control of their schedule- volume or complexity. One doctor told me she was told by her employer that she would have to return part of her salary if she did not have a 100% patient satisfaction survey.

Patients demand their prophylactic and unnecessary antibiotic and narcotic prescriptions- good doctors say ‘no’… but, place themselves at risk for admonishment or penalty if their patients are unhappy. Not to mention being embarrassed by the published report card, or a low star-rating on an internet site, like Health Grades- who by the way clearly states that a physician has no right to remove their profile from their web site unless “they die, or retire from practice”. Who are those guys, anyway?

The diminished importance of quality of patient care and safety is evident in the licensing of untrained, inexperienced mid level providers to practice medicine, the replacement of nurses with medical assistants, the overloading of schedules and understaffing of clinics, and the importance of how happy a patient is, rather than the quality of care they are receiving.

Physicians have absolute responsibility- without comparable choices or control within their profession.

So, I am all for being supportive of our peers at every level of education and practice- Sign me up!-, but, let’s get real- and take a hard look at what is really driving physicians to make that ultimate life-ending choice- maybe, it is the only choice they believe they can control…

Sue, I agree that all these other factors matter. A lot! But where does the assault on our humanity start? The assault on our humanity that leads us each to accept the life of an abused doctor as the norm. We have been abused and will continue to be abused: https://www.idealmedicalcare.org/blog/physician-burnout-is-physician-abuse/

The truth is a dysfunctional medical system can only exist on the backs of a disempowered physician population—the precursor of which is an abused medical student population.

Normal people would never succumb to such treatment. Physicians do. Why?

Your comments with Dr. Sinskey are so pertinent and needed, Dr. Wible. I have always practice relationship based medicine with contacts with my patients. I treated them as family listened to their needs and desires as well as their fears.

Unfortunately the hierarchy in the present state of the affordable care act this and oil for this method of practicing medicine.

Before a change can occur in the American Medical Association in the medical societies in the United States must take a firm and uncompromising position to return medicine to a relationship based profession. Medical schools and medical boards must must teach these principles of medical care – patient relationships and respect for doctors in training and practice.

Standards the respect must be formulated and protected by laws, in order for relationship based medicine to continue to survive!

Best regards,

Dr. John – March 2, 2016